A Cross-Cultural Comparison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Privacy and the Internet of Things

CENTER FOR LONG-TERM CYBERSECURITY CLTC OCCASIONAL WHITE PAPER SERIES Privacy and the Internet of Things EMERGING FRAMEWORKS FOR POLICY AND DESIGN GILAD ROSNER AND ERIN KENNEALLY CLTC OCCASIONAL WHITE PAPER SERIES Privacy and the Internet of Things EMERGING FRAMEWORKS FOR POLICY AND DESIGN GILAD ROSNER, PH.D. Founder, IoT Privacy Forum ERIN KENNEALLY, J.D. Cyber Security Division, Science & Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security (Author contributions to this work were done in her personal capacity. The views expressed are her own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Homeland Security or the United States Government.) CENTER FOR LONG-TERM CYBERSECURITY iv PRIVACY AND THE INTERNET OF THINGS Contents Executive Summary 2 Acknowledgments 4 Internet of Things 101 5 Key Privacy Risks and Challenges 6 A Shift from Online to Offline Data Collection 7 Diminishment of Private Spaces 8 Bodily and Emotional Privacy 9 Choice and Meaningful Consent 10 Regulatory Issues Specific to the IoT 12 Emerging Frameworks and Strategies 13 Omnibus Privacy Policy 13 Improved User Control and Management 14 Identity Management 15 Notification 16 Summary 18 Conclusion 19 Endnotes 20 About the Authors 22 1 PRIVACY AND THE INTERNET OF THINGS Executive Summary The proliferation of network-connected devices, also known as the “Internet of Things” (IoT), offers unprecedented opportunities for consumers and businesses. Yet devices such as fitness trackers, personal home assistants (e.g., Amazon Echo, Google Home), and digital appliances are changing the nature of privacy as they operate silently in the background while transmitting data about a broad range of human activities and behaviors. -

The Privacy Paradox and the Internet-Of-Things Meredydd Williams, Jason R

1 The Perfect Storm: The Privacy Paradox and the Internet-of-Things Meredydd Williams, Jason R. C. Nurse and Sadie Creese Department of Computer Science University of Oxford Oxford, UK ffi[email protected] Abstract—Privacy is a concept found throughout human his- and colleagues discovered that individuals neglect privacy tory and opinion polls suggest that the public value this principle. concerns while making purchases [9]. Researchers found that However, while many individuals claim to care about privacy, 74% of US respondents had location-based services enabled, they are often perceived to express behaviour to the contrary. This phenomenon is known as the Privacy Paradox and its exchanging sensitive information for convenience [10]. This existence has been validated through numerous psychological, presents the ‘Privacy Paradox’ [11], where individuals claim to economic and computer science studies. Several contributory value their privacy but appear to not act accordingly. Previous factors have been suggested including user interface design, risk work has suggested that a number of factors, including user salience, social norms and default configurations. We posit that interface design [12], risk salience [13] and privacy settings the further proliferation of the Internet-of-Things (IoT) will aggravate many of these factors, posing even greater risks to [14], can exacerbate this disparity between claim and action. individuals’ privacy. This paper explores the evolution of both The Internet-of-Things (IoT) promises to be the digital the paradox and the IoT, discusses how privacy risk might alter revolution of the twenty-first century [15]. It has the potential over the coming years, and suggests further research required to connect together a vast number of ubiquitous components, to address a reasonable balance. -

A Survey of Social Media Users Privacy Settings & Information Disclosure

Edith Cowan University Research Online Australian Information Security Management Conference Conferences, Symposia and Campus Events 2016 A survey of social media users privacy settings & information disclosure Mashael Aljohani Security & Forensic Research Group, Auckland University of Technology Alastair Nisbet Security & Forensic Research Group, Auckland University of Technology Kelly Blincoe Security & Forensic Research Group, Auckland University of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ism Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, and the Information Security Commons DOI: 10.4225/75/58a693deee893 Aljohani, M., Nisbet, A., & Blincoe, K. (2016). A survey of social media users privacy settings & information disclosure. In Johnstone, M. (Ed.). (2016). The Proceedings of 14th Australian Information Security Management Conference, 5-6 December, 2016, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Western Australia. (pp.67-75). This Conference Proceeding is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ism/198 A SURVEY OF SOCIAL MEDIA USERS PRIVACY SETTINGS & INFORMATION DISCLOSURE Mashael Aljohani1,2, Alastair Nisbet1,2, Kelly Blincoe2, 1Security & Forensic Research Group, 2Auckland University of Technology Auckland, New Zealand [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This research utilises a comprehensive survey to ascertain the level of social networking site personal information disclosure by members at the time of joining the membership and their subsequent postings to the sites. Areas examined are the type of information they reveal, their level of knowledge and awareness regarding how their information is protected by SNSs and the awareness of risks that over-sharing may pose. Additionally, this research studies the effect of gender, age, education, and level of privacy concern on the amount and kind of personal information disclosure and privacy settings applied. -

Recommending Privacy Settings for Internet-Of-Things

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations December 2019 Recommending Privacy Settings for Internet-of-Things Yangyang He Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation He, Yangyang, "Recommending Privacy Settings for Internet-of-Things" (2019). All Dissertations. 2528. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/2528 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommending Privacy Settings for Internet-of-Things A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Computer Science by Yang He December 2019 Accepted by: Dr. Bart P. Knijnenburg, Committee Chair Dr. Larry F. Hodges Dr. Alexander Herzog Dr. Ilaria Torre Abstract Privacy concerns have been identified as an important barrier to the growth of IoT. These concerns are exacerbated by the complexity of manually setting privacy preferences for numerous different IoT devices. Hence, there is a demand to solve the following, urgent research question: How can we help users simplify the task of managing privacy settings for IoT devices in a user-friendly manner so that they can make good privacy decisions? To solve this problem in the IoT domain, a more fundamental understanding of the logic behind IoT users' privacy decisions in different IoT contexts is needed. We, therefore, conducted a series of studies to contextualize the IoT users' decision-making characteristics and designed a set of privacy-setting interfaces to help them manage their privacy settings in various IoT contexts based on the deeper understanding of users' privacy decision behaviors. -

Modeling and Analyzing Privacy in Social Networks

Session: Research Track - Privacy SACMAT’18, June 13-15, 2018, Indianapolis, IN, USA My Friend Leaks My Privacy: Modeling and Analyzing Privacy in Social Networks Lingjing Yu1;2, Sri Mounica Motipalli3, Dongwon Lee4, Peng Liu4, Heng Xu4, Qingyun Liu1;2, Jianlong Tan1;2, and Bo Luo3 1 Institute of Information Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 3 Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, The University of Kansas, USA 4 School of Information Science and Technology, The Pennsylvania State University, USA [email protected],[email protected],[email protected],[email protected], [email protected],[email protected],[email protected],[email protected] ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION With the dramatically increasing participation in online social net- In recent years, many online social network services (SNSs) such as works (OSNs), huge amount of private information becomes avail- Facebook have become extremely popular, attracting a large num- able on such sites. It is critical to preserve users’ privacy without ber of users to generate and share diverse (personal) contents. With preventing them from socialization and sharing. Unfortunately, ex- the advancement of information retrieval and search techniques, on isting solutions fall short meeting such requirements. We argue the other hand, it has become easier to do web-scale identification that the key component of OSN privacy protection is protecting and extraction of users’ personal information from SNSs. There- (sensitive) content – privacy as having the ability to control informa- fore, malicious or curious users could take an advantage of these tion dissemination. -

HTTP Cookie Hijacking in the Wild: Security and Privacy Implications Suphannee Sivakorn*, Jason Polakis* and Angelos D

HTTP Cookie Hijacking in the Wild: Security and Privacy Implications Suphannee Sivakorn*, Jason Polakis* and Angelos D. Keromytis [suphannee, polakis, angelos]@cs.columbia.edu Columbia University, New York NY, USA *Joint primary authors The widespread demand for online privacy, also fueled by widely-publicized demonstrations of session hijacking attacks against popular websites, has spearheaded the increasing deployment of HTTPS. However, many websites still avoid ubiquitous encryption due to performance or compatibility issues. The prevailing approach in these cases is to force critical functionality and sensitive data access over encrypted connections, while allowing more innocuous functionality to be accessed over HTTP. In practice, this approach is prone to flaws that can expose sensitive information or functionality to third parties. In this work, we conduct an in-depth assessment of a diverse set of major websites and explore what functionality and information is exposed to attackers that have hijacked a user’s HTTP cookies. We identify a recurring pattern across websites with partially deployed HTTPS; service personalization inadvertently results in the exposure of private information. The separation of functionality across multiple cookies with different scopes and inter-dependencies further complicates matters, as imprecise access control renders restricted account functionality accessible to non-session cookies. Our cookie hijacking study reveals a number of severe flaws; attackers can obtain the user’s home and work address and visited websites from Google, Bing and Baidu expose the user’s complete search history, and Yahoo allows attackers to extract the contact list and send emails from the user’s account. Furthermore, e-commerce vendors such as Amazon and Ebay expose the user’s purchase history (partial and full respectively), and almost every website exposes the user’s name and email address. -

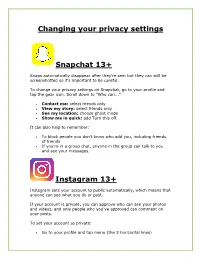

Changing Your Privacy Settings Snapchat 13+ Instagram

Changing your privacy settings Snapchat 13+ Snaps automatically disappear after they're sent but they can still be screenshotted so it's important to be careful. To change your privacy settings on Snapchat, go to your profile and tap the gear icon. Scroll down to "Who can...” Contact me: select friends only View my story: select friends only See my location: choose ghost mode Show me in quick: add Turn this off. It can also help to remember: To block people you don't know who add you, including friends of friends If you're in a group chat, anyone in the group can talk to you and see your messages. Instagram 13+ Instagram sets your account to public automatically, which means that anyone can see what you do or post. If your account is private, you can approve who can see your photos and videos, and only people who you've approved can comment on your posts. To set your account as private: Go to your profile and tap menu (the 3 horizontal lines) Tap settings Scroll down to Private Account and turn this on. Remember that you can still block and report anyone who is bullying you on Instagram. WhatsApp 16+ WhatsApp will automatically allow people to see what's on your profile and when you were last on. Changing your privacy settings can help to keep you safe and stop people bullying or abusing you. To change your settings: Go to your profile Select Account and then Privacy. You can change the following settings: Last seen you can change this to My Contacts to stop people you don't know seeing if you've been online. -

Role of Security in Social Networking

(IJACSA) International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2016 Role of Security in Social Networking David Hiatt Young B. Choi College of Arts & Sciences College of Arts & Sciences Regent University Regent University Virginia Beach, Virginia, U.S.A. Virginia Beach, Virginia, U.S.A. Abstract—In this paper, the concept of security and privacy in According to [2], the staggering popularity of these social social media, or social networking will be discussed. First, a brief networks, which are often used by teenagers and people who history and the concept of social networking will be introduced. do not have privacy or security on their minds, leads to a huge Many of the security risks associated with using social media are amount of potentially private information being placed on the presented. Also, the issue of privacy and how it relates to Internet where others can have access to it. She goes on to say security are described. Based on these discussions, some that interacting with people is not new, but this medium for solutions to improve a user’s privacy and security on social doing it is relatively new. She says, “Social networking sites networks will be suggested. Our research will help the readers to have become popular sites for youth culture to explore understand the security and privacy issues for the social network themselves, relationships, and share cultural artifacts. These users, and some steps which can be taken by both users and sites centralize and help coordinate the interpersonal exchanges social network organizations to help improve security and privacy. -

Security and Privacy of Smartphone Messaging Applications1

2014 978-1-4503-3001-5/14/125 Security and Privacy of Smartphone Messaging Applications1 Robin Mueller Vienna University of Technology, Austria [email protected] Sebastian Schrittwieser St. Poelten University of Applied Sciences, Austria [email protected] Peter Fruehwirt SBA Research, Austria [email protected] Peter Kieseberg SBA Research, Austria [email protected] Edgar Weippl SBA Research, Austria [email protected] In recent years mobile messaging and VoIP applications for smartphones have seen a massive surge in popularity, which has also sparked the interest in research related to the security and privacy of these applications. Various security researchers and institutions have performed in-depth analyses of specific applications or vulnerabilities. This paper gives an overview of the status quo in terms of security for a number of selected applications in comparison to a previous evaluation conducted two years ago, as well as performing an analysis on some new applications. The evaluation methods mostly focus on known vulnerabilities in connection with authentication and validation mechanisms but also describe some newly identified attack vectors. The results show a predominantly positive trend for new applications, which are mostly being developed with robust security and privacy features, while some of the older applications have shown little to no progress in this regard or have even introduced new vulnerabilities in recent versions. In addition, this paper shows privacy implications of smartphone messaging that are not even solved by today’s most sophisticated “secure” smartphone messaging applications, as well as discuss methods for protecting user privacy during the creation of the user network. -

Lessons Learnt from Comparing Whatsapp Privacy Concerns Across

Lessons Learnt from Comparing WhatsApp Privacy Concerns Across Saudi and Indian Populations Jayati Dev, Indiana University; Pablo Moriano, Oak Ridge National Laboratory; L. Jean Camp, Indiana University https://www.usenix.org/conference/soups2020/presentation/dev This paper is included in the Proceedings of the Sixteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security. August 10–11, 2020 978-1-939133-16-8 Open access to the Proceedings of the Sixteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security is sponsored by USENIX. Lessons Learnt from Comparing WhatsApp Privacy Concerns Across Saudi and Indian Populations Jayati Dev Pablo Moriano∗ L. Jean Camp Indiana University Oak Ridge National Laboratory Indiana University Bloomington, IN, USA Oak Ridge, TN, USA Bloomington, IN, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract 1 Introduction WhatsApp is a multimedia messaging application with a The purpose of this study is to understand the privacy con- range of capabilities beyond traditional text messaging: asyn- cerns and behavior of non-WEIRD populations in online mes- chronous chat, photo sharing, video sharing, synchronous saging platforms. Analysis of surveys (n = 674) of WhatsApp voice and video chat, and location sharing [14]. WhatsApp users in Saudi Arabia and India revealed that Saudis had sig- supports two-person conversations, ad-hoc discussions, and nificantly higher concerns about being contacted by strangers. larger long-lived structured groups. Due to the penetration In contrast, Indians showed significantly higher concerns with of WhatsApp in several non-western countries and it being respect to social contact from professional colleagues. Demo- widely considered for peer-to-peer information sharing, there graphics impinge privacy preferences in both populations, but is an opportunity to study differences and similarities in pri- in different ways. -

17 Collective Privacy Management in Social Media: a Cross-Cultural

Collective Privacy Management in Social Media: A Cross-Cultural Validation HICHANG CHO, National University of Singapore BART KNIJNENBURG, Clemson University ALFRED KOBSA and YAO LI, University of California, Irvine If one wants to study privacy from an intercultural perspective, one must first validate whether there are any cultural variations in the concept of “privacy” itself. This study systematically examines cultural differences in collective privacy management strategies, and highlights methodological precautions that must be taken in quantitative intercultural privacy research. Using survey data of 498 Facebook users from the US, Singa- pore, and South Korea, we test the validity and cultural invariance of the measurement model and predictive model associated with collective privacy management. The results show that the measurement model is only partially culturally invariant, indicating that social media users in different countries interpret the same in- struments in different ways. Also, cross-national comparisons of the structural model show that causal path- ways from collective privacy management strategies to privacy-related outcomes vary significantly across countries. The findings suggest significant cultural variations in privacy management practices, bothwith regard to the conceptualization of its theoretical constructs, and with respect to causal pathways. 17 CCS Concepts: • Security and privacy → Human and societal aspects of security and privacy; Additional Key Words and Phrases: Privacy, collective privacy management, social media, measurement in- variance ACM Reference format: Hichang Cho, Bart Knijnenburg, Alfred Kobsa, and Yao Li. 2018. Collective Privacy Management in Social Media: A Cross-Cultural Validation. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 25, 3, Article 17 (June 2018), 33 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/3193120 1 INTRODUCTION As privacy risks have become omnipresent and increasingly unpredictable in today’s networked society, privacy management has been a salient issue for consumers, researchers, and practitioners. -

Privacy and Security Issues in Online Social Networks

future internet Article Privacy and Security Issues in Online Social Networks Shaukat Ali 1,*, Naveed Islam 1, Azhar Rauf 2, Ikram Ud Din 3 and Mohsen Guizani 4 and Joel J. P. C. Rodrigues 5,6,7 1 Department of Computer Science, Islamia College University, Peshawar 25120, Pakistan; [email protected] 2 Department of Computer Science, University of Peshawar, Peshawar 25120, Pakistan; [email protected] 3 Department of Information Technology, The University of Haripur, Haripur 22620, Pakistan; [email protected] 4 Computer Science and Engineering Department, Qatar University, Doha 2713, Qatar; [email protected] 5 Post-graduation, National Institute of Telecommunications (Inatel), 37540-000 Santa Rita do Sapucaí-MG, Brazil; [email protected] 6 Covilhã Delegation, Instituto de Telecomunicações, 1049-001 Lisbon, Portugal 7 PPGIA, University of Fortaleza (UNIFOR), 90811-905 Fortaleza-CE, Brazil * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 September 2018; Accepted: 21 November 2018; Published: 22 November 2018 Abstract: The advent of online social networks (OSN) has transformed a common passive reader into a content contributor. It has allowed users to share information and exchange opinions, and also express themselves in online virtual communities to interact with other users of similar interests. However, OSN have turned the social sphere of users into the commercial sphere. This should create a privacy and security issue for OSN users. OSN service providers collect the private and sensitive data of their customers that can be misused by data collectors, third parties, or by unauthorized users. In this paper, common security and privacy issues are explained along with recommendations to OSN users to protect themselves from these issues whenever they use social media.