Applicability of Periodization to Orchestral Audition Preparation on Trombone: a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

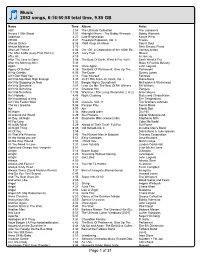

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

Hype Funk Score Avg. Hype Funk Score Funk Score Avg Funk Score Combined Funk 1 Flashlight

Barely Somewhat Extra Hella Response Hype Funk Avg. Hype Avg Funk Combined # answer options No Funky Funky Funky Funky Funky Da Bomb Count Score Funk Score Funk Score Score Funk 1 Flashlight - Parliament 0 0 0 2 0 5 14 21 108.00 5.14 136.00 6.48 11.62 Give Up The Funk (Tear the Roof Off the 2 Sucker) - Parliament 0 0 0 0 2 6 12 20 102.00 5.10 130.00 6.50 11.60 3 One Nation Under A Groove - Funcakelic 0 1 0 0 2 2 13 18 92.00 5.11 115.00 6.39 11.50 4 Atomic Dog - George Clinton 0 0 0 1 4 5 15 25 124.00 4.96 159.00 6.36 11.32 More Bounce To The Ounce - Zapp & 5 Roger 0 0 0 2 0 5 9 16 78.00 4.88 101.00 6.31 11.19 6 (Not Just) Knee Deep - Funkadelic 0 0 0 0 5 6 12 23 111.00 4.83 145.00 6.30 11.13 7 Mothership Connection - Parliament 0 0 0 0 3 6 8 17 81.00 4.76 107.00 6.29 11.06 8 Payback - James Brown 0 0 1 1 4 0 10 16 75.00 4.69 97.00 6.06 10.75 Get the Funk Out Ma Face - The Brothers 9 Johnson 0 0 0 1 4 4 8 17 78.00 4.59 104.00 6.12 10.71 10 Slide - Slave 0 0 0 1 1 6 5 13 59.00 4.54 80.00 6.15 10.69 11 Super Freak - Rick James 0 0 1 3 1 3 8 16 70.00 4.38 94.00 5.88 10.25 12 Pass the Peas - Fred Wesley and the JBs 0 0 1 1 2 2 5 11 47.00 4.27 64.00 5.82 10.09 13 The Jam - Graham Central Station 0 0 1 2 0 3 5 11 47.00 4.27 64.00 5.82 10.09 14 Jamaica Funk - Tom Browne 0 0 1 2 2 4 6 15 63.00 4.20 87.00 5.80 10.00 15 Fire - Ohio Players 0 0 0 2 7 3 7 19 79.00 4.16 110.00 5.79 9.95 16 Maggot Brain - Funkadelic 0 0 1 1 3 3 5 13 54.00 4.15 75.00 5.77 9.92 17 Dr. -

Print Complete Desire Full Song List

R & B /POP /FUNK /BEACH /SOUL /OLDIES /MOTOWN /TOP-40 /RAP /DANCE MUSIC ‘50s/ ‘60s MUSIC ARETHA FRANKLIN: ISLEY BROTHERS: SAM COOK: RESPECT SHOUT TWISTIN THE NIGHT AWAY NATURAL WOMAN JAMES BROWN: YOU SEND ME ARTHUR CONLEY: I FEEL GOOD SMOKEY ROBINSON & THE MIRACLES: SWEET SOUL MUSIC I'T'S A MAN'S MAN'S WORLD OOH BABY BABY DIANA ROSS & THE SUPREMES: PLEASE,PLEASE,PLEASE TAMS: BABY LOVE LLOYD PRICE: BE YOUNG BE FOOLISH BE HAPPY STOP! IN THE NAME OF LOVE STAGGER LEE WHAT KIND OF FOOL YOU CAN’T HURRY LOVE MARY WELLS: TEMPTATIONS: YOU KEEP ME HANGIN ON MY GUY AIN’T TOO PROUD TO BEG DION: MARTHA & THE VANDELLAS: I WISH IT WOULD RAIN RUN AROUND SUE DANCING IN THE STREET MY GIRL DRIFTERS & BEN E. KING: HEATWAVE THE WAY YOU DO THE THINGS YOU DO DANCE WITH ME MARVIN GAYE: THE DOMINOES: I’VE GOT SAND IN MY SHOES AIN’T NOTHING LIKE THE REAL THING SIXTY MINUTE MAN RUBY RUBY HOW SWEET IT IS TO BE LOVED BY YOU TINA TURNER: SATURDAY NIGHT AT THE MOVIES I HEARD IT THROUGH THE GRAPEVINE PROUD MARY STAND BY ME OTIS REDDING: WILSON PICKET: THERE GOES MY BABY DOCK OF THE BAY 634-5789 UNDER THE BOARDWALK THAT’S HOW STRONG MY LOVE IS DON’T LET THE GREEN GRASS FOOL YOU UP ON TH ROOF PLATTERS: IN THE MIDNIGHT HOUR EDDIE FLOYD: WITH THIS RING MUSTANG SALLY KNOCK ON WOOD RAY CHARLES ETTA JAMES: GEORGIA ON MY MIND AT LAST SAM AND DAVE: FOUR TOPS: HOLD ON I'M COMING BABY I NEED YOUR LOVING SOUL MAN CAN'T HELP MYSELF REACH OUT I'LL BE THER R & B /POP /FUNK /BEACH /SOUL /OLDIES /MOTOWN /TOP-40 /RAP /DANCE MUSIC ‘70s MUSIC AL GREEN: I WANT YOU BACK ROD STEWART: LOVE AND HAPPINESS JAMES BROWN: DA YA THINK I’M SEXY? ANITA WARD: GET UP ROLLS ROYCE: RING MY BELL THE PAYBACK CAR WASH BILL WITHERS: JIMMY BUFFETT: SISTER SLEDGE: AIN’T NO SUNSHINE MARGARITAVILLE WE ARE FAMILY BRICK: K.C. -

From the on Inal Document. What Can I Write About?

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 470 655 CS 511 615 TITLE What Can I Write about? 7,000 Topics for High School Students. Second Edition, Revised and Updated. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-5654-1 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 153p.; Based on the original edition by David Powell (ED 204 814). AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock no. 56541-1659: $17.95, members; $23.95, nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS High Schools; *Writing (Composition); Writing Assignments; *Writing Instruction; *Writing Strategies IDENTIFIERS Genre Approach; *Writing Topics ABSTRACT Substantially updated for today's world, this second edition offers chapters on 12 different categories of writing, each of which is briefly introduced with a definition, notes on appropriate writing strategies, and suggestions for using the book to locate topics. Types of writing covered include description, comparison/contrast, process, narrative, classification/division, cause-and-effect writing, exposition, argumentation, definition, research-and-report writing, creative writing, and critical writing. Ideas in the book range from the profound to the everyday to the topical--e.g., describe a terrible beauty; write a narrative about the ultimate eccentric; classify kinds of body alterations. With hundreds of new topics, the book is intended to be a resource for teachers and students alike. (NKA) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the on inal document. -

Big Blast & the Party Masters

BIG BLAST & THE PARTY MASTERS 2018 Song List ● Aretha Franklin - Freeway of Love, Dr. Feelgood, Rock Steady, Chain of Fools, Respect, Hello CURRENT HITS Sunshine, Baby I Love You ● Average White Band - Pick Up the Pieces ● B-52's - Love Shack - KB & Valerie+A48 ● Beatles - I Want to Hold Your Hand, All You Need ● 5 Seconds of Summer - She Looks So Perfect is Love, Come Together, Birthday, In My Life, I ● Ariana Grande - Problem (feat. Iggy Azalea), Will Break Free ● Beyoncé & Destiny's Child - Crazy in Love, Déjà ● Aviici - Wake Me Up Vu, Survivor, Halo, Love On Top, Irreplaceable, ● Bruno Mars - Treasure, Locked Out of Heaven Single Ladies(Put a Ring On it) ● Capital Cities - Safe and Sound ● Black Eyed Peas - Let's Get it Started, Boom ● Ed Sheeran - Sing(feat. Pharrell Williams), Boom Pow, Hey Mama, Imma Be, I Gotta Feeling Thinking Out Loud ● The Bee Gees - Stayin' Alive, Emotions, How Deep ● Ellie Goulding - Burn Is You Love ● Fall Out Boy - Centuries ● Bill Withers - Use Me, Lovely Day ● J Lo - Dance Again (feat. Pitbull), On the Floor ● The Blues Brothers - Everybody Needs ● John Legend - All of Me Somebody, Minnie the Moocher, Jailhouse Rock, ● Iggy Azalea - I'm So Fancy Sweet Home Chicago, Gimme Some Lovin' ● Jessie J - Bang Bang(Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj) ● Bobby Brown - My Prerogative ● Justin Timberlake - Suit and Tie ● Brass Construction - L-O-V-E - U ● Lil' Jon Z & DJ Snake - Turn Down for What ● The Brothers Johnson - Stomp! ● Lorde - Royals ● Brittany Spears - Slave 4 U, Till the World Ends, ● Macklemore and Ryan Lewis - Can't Hold Us Hit Me Baby One More Time ● Maroon 5 - Sugar, Animals ● Bruno Mars - Just the Way You Are ● Mark Ronson - Uptown Funk (feat. -

Gender, Race and Popular Culture a Dissertation Submitted In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Feminism Without Feminists: Gender, Race and Popular Culture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Linda Jin Kim August 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Toby Miller, Co-Chairperson Dr. Ellen Reese, Co-Chairperson Dr. Scott Coltrane Dr. Scott Brooks Copyright by Linda Jin Kim 2010 The Dissertation of Linda Jin Kim is approved: _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ Committee Co-Chairperson _____________________________________________________ Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This dissertation has truly been a labor of love. I am blessed to have amazing faculty whom I admire and respect on my committee. My mentor, Toby Miller, has been with me since the inception of this project and has never failed in challenging me to expand my intellectual horizons and to sharpen my critical thinking skills. Ellen Reese, Scott Coltrane, and Scott Brooks have equally been significant figures throughout the various phases of my academic career. I would be remiss not to mention Karen Pyke and Jane Ward. Collectively, they have offered me invaluable wisdom, advice, and encouragement. I also wish to express gratitude to my meticulous research assistants, Allie Green, Alan Truong, and Angela Wagner, for transcribing the bulk of my interviews. In addition, I clocked in a lot of hours at my two local coffee shops on Ocean Park Boulevard and on Colorado Avenue (“my virtual mobile offices”). I have probably spent more face time with the baristas there than anyone else while I have been dissertating. I thank all of them, especially Alex, Bastian, and Steven. -

Establishing Female Resistance As Tradition in Country Music: Towards a More Refined Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-19-2016 12:00 AM Establishing Female Resistance as Tradition in Country Music: Towards a More Refined Discourse Catherine Keron The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Norma Coates The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Catherine Keron 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Recommended Citation Keron, Catherine, "Establishing Female Resistance as Tradition in Country Music: Towards a More Refined Discourse" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3970. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3970 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This thesis analyzes facets of resistance in the lyrics of female country music performers and explores how their articulations of female resistance draw on and rework Appalachian folk traditions within country music. Beginning with the musical practices of Appalachian women, who used music to lament their lives restricted by domestic responsibilities, this thesis examines expressions of female resistance through lyrical analysis, with a concentration on female country performers from 1995 to the present. Despite evolving into a performance tradition, female resistance in country music continues to address the lived experiences of its female audience. As such, the female resistance tradition is an enduring component of country music that has addressed women’s issues for over a century. -

Copyright by Michael Lee Harland 2019

Copyright by Michael Lee Harland 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Michael Lee Harland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “My Life Transparently Revealed”: Interpreting Mahler’s Worldview through an Analysis of His Middle-Period Symphonies Committee: Michael C. Tusa, Supervisor Andrew Dell’Antonio Robert S. Hatten Kathleen M. Higgins Luisa Nardini “My Life Transparently Revealed”: Interpreting Mahler’s Worldview through an Analysis of His Middle-Period Symphonies by Michael Lee Harland Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 Dedication To my wife, Jenna Harland Acknowledgements I wish there were room to express all the ways I have benefited from the mentorship of Michael C. Tusa. Over the past six years, I have thoroughly enjoyed the seminars, the conversations, and above all, friendship. If one were to add up the many hours he has spent guiding me in this endeavor, it would be a true testament to his dedication as a teacher. I could not have completed this project without his advocating for me to receive a Continuing Fellowship during this last year of writing. My deepest thanks. Special thanks to Robert S. Hatten, whose seminars and writings on issues of musical meaning form so much of the theoretical core of this project. He has profoundly influenced my thoughts in this regard, but most importantly, his generosity in providing time and feedback have benefited me enormously. -

TFC Song List Alphabetized by Genre Then Artist

TFC Song List alphabetized by Genre then Artist James & Bobby Purify - I'm Your Puppet Mary J Blige - Crumped • Acoustic, Folk, and Blues B.B. King - The Thrill Is Gone • Contemporary and Dance 50 Cent - The Club Alicia Keyes - I Ain't Got You Arthur Connelly - Do You Like Good Music Black Street - No Diggity Bobby Brown - Humpin Around Bobby Brown - My Prerogative Boyz II Men - End Of The Road Boyz II Men - I'll Make Love To You Brian Mcknight - Crazy Love Brick - Ain't Gonna Hurt Nobody Brick - Disco Jazz Cameo - Back And Forth Cameo - Candy Cameo - Close Quarters Cameo - Single Life Cameo - Word Up Color Me Badd - Sex You Up E.U. - Da Butt Earth Wind & Fire - Let's Groove Tonight Earth Wind & Fire - September Earth Wind & Fire - Shining Star Harold Melvin - If You Don't Know Me By Now Janet Jackson - Alright Janet Jackson - Miss You Much Janet Jackson - Rhythm Nation Janet Jackson - That's The Way Love Goes Marcia Griffith - Electric Slide Michael Jackson - Abc Michael Jackson - Dancin Machine Michael Jackson - Remember The Time Michael Jackson - Stop The Love Michael Jackson - The Way You Make Me Feel Outkast - Hey Ya Outkast - I Like The Way You Move Prince - 1999 Prince - Delirious Prince - Dmsr Prince - Let's Go Crazy Prince - Money Don't Matter Prince - Pop Life R. Kelly - Bump And Grind R. Kelly - Steppin Shaggy - You're My Angel The Time - Cool The Time - Jungle Love Usher - Yeah, Yeah Whitney Houston - I Will Always Love You • Country and Bluegrass Johnnie Gill - Fair Weather Friends Johnnie Gill - My, My My Keith Sweat - Keep It Coming • Modern, Alternative, and Classic Rock Bozz Scaggs - Dirty Low Down Chicago - Color My World Gap Band - Burn Rubber Drop The Bomb Hall & Oates - I Can't Go For That L.T.D. -

Tony's Itunes Library

Music 2053 songs, 6:16:50:58 total time, 9.85 GB Name Time Album Artist ABC 2:54 The Ultimate Collection The Jackson 5 Across 110th Street 3:51 Midnight Mover - The Bobby Womack ... Bobby Womack Addiction 4:27 Late Registration Kanye West AEIOU 8:41 Freestyle Explosion, Vol. 3 Freeze African Dance 6:08 1989 Keep On Movin' Soul II Soul African Mailman 3:10 Nina Simone Piano Afro Loft Theme 6:06 Om 100: A Celebration of the 100th Re... Various Artists The After 6 Mix (Juicy Fruit Part Ll) 3:25 Juicy Fruit Mtume After All 4:19 Al Jarreau After The Love Is Gone 3:58 The Best Of Earth, Wind & Fire Vol.II Earth Wind & Fire After the Morning After 5:33 Maze ft Frankie Beverly Again 5:02 Once Again John Legend Agony Of Defeet 4:28 The Best Of Parliament: Give Up The ... Parliament Ai No Corrida 6:26 The Dude Quincy Jones Ain't Gon' Beg You 4:14 Free Yourself Fantasia Ain't No Mountain High Enough 3:30 25 #1 Hits From 25 Years, Vol. I Diana Ross Ain't No Stopping Us Now 7:03 Boogie Nights Soundtrack McFadden & Whitehead Ain't No Sunshine 2:07 Lean On Me: The Best Of Bill Withers Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine 3:44 Greatest Hits Dangelo Ain't No Sunshine 11:04 Wattstax - The Living Word (disc 2 of 2) Isaac Hayes Ain't Nobody 4:48 Night Clubbing Rufus and Chaka Kahn Ain't too proud to beg 2:32 The Temptations Ain't We Funkin' Now 5:36 Classics, Vol. -

The New Television Masculinity in Rescue Me, Nip/Tuck, the Shield

Rescuing Men: The New Television Masculinity In Rescue Me, Nip/Tuck, The Shield, Boston Legal, & Dexter A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Pamela Hill Nettleton IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Mary Vavrus, Ph.D, Adviser November 2009 © Pamela Hill Nettleton, November/2009 i Acknowledgements I have had the extreme good fortune of benefitting from the guidance, insight, wit, and wisdom of a committee of exceptional and accomplished scholars. First, I wish to thank my advisor, Mary Vavrus, whose insightful work in feminist media studies and political economy is widely respected and admired. She has been an inspiring teacher, an astute critic, and a thoughtful pilot for me through this process, and I attempt to channel her dignity and competence daily. Thank you to my committee chair, Gilbert Rodman, for his unfailing encouragement and support and for his perceptive insights; he has a rare gift for challenging students while simultaneously imbuing them with confidence. Donald Browne honored me with his advice and participation even as he prepared to ease his way out of active teaching, and I learned from him as his student, as his teaching assistant, and as a listener to what must be only a tiny part of his considerable collection of modern symphonic music. Jacqueline Zita’s combination of theoretical acumen and pragmatic activism is the very definition of a feminist scholar, and my days in her classroom were memorable. Laurie Ouellette is a polished and flawless extemporaneous speaker and teacher, and her writing on television is illuminating; I have learned much from her. -

Trumpet Music of David Sampson: a Performer's Guide to "Breakaway," "Passage," and "Triptych"

Please do not remove this page Trumpet Music of David Sampson: A Performer's Guide to "Breakaway," "Passage," and "Triptych" Flynn, Michael Patrick https://scholarship.miami.edu/discovery/delivery/01UOML_INST:ResearchRepository/12355343050002976?l#13355509850002976 Flynn, M. P. (2010). Trumpet Music of David Sampson: A Performer’s Guide to “Breakaway,” “Passage,” and “Triptych” [University of Miami]. https://scholarship.miami.edu/discovery/fulldisplay/alma991031447558902976/01UOML_INST:ResearchR epository Open Downloaded On 2021/09/30 13:18:38 -0400 Please do not remove this page UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI TRUMPET MUSIC OF DAVID SAMPSON: A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO “BREAKAWAY,” “PASSAGE,” AND “TRIPTYCH” By Michael Patrick Flynn A DOCTORAL ESSAY Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Miami in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Coral Gables, Florida May 2010 @ 2010 Michael Patrick Flynn All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI An essay submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts TRUMPET MUSIC OF DAVID SAMPSON: A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO “BREAKAWAY,” “PASSAGE,” AND “TRIPTYCH” Michael Patrick Flynn Approved: Craig Morris, M.M. Terri A. Scandura, Ph.D. Professor of Dean of the Graduate School Instrumental Performance Gary Green, M.M. Dennis Kam, D.M.A. Professor of Professor of Instrumental Performance Music Theory and Composition Thomas M. Sleeper, M.M. Professor of Instrumental Performance FLYNN, MICHAEL PATRICK (D.M.A., Instrumental Performance) Trumpet Music of David Sampson: (May 2010) A Performer’s Guide to “Breakaway,” “Passage,” and “Triptych” Abstract of a doctoral essay at the University of Miami. Doctoral essay supervised by Professor Craig Morris.