4. Case Study:; Chinese Eel Exports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

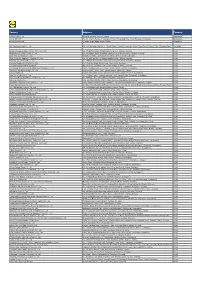

中国输美木制工艺品注册登记企业名单registered Producing

中国输美木制工艺品注册登记企业名单 Registered Producing Industries of Wooden Handicrafts of China Exported to the U.S. 注册登记编号 序号 所在省份 所在城市 企业名称 企业地址 Registered Number Province City Company Name Company Address Number 天津市北辰区双口镇双河村30号 天津津长工艺品加工厂 天津 天津 NO.30, SHUANGHE VILLAGE, 1 TIANJIN JINCHANG ARTS & 1206ZMC0087 TIANJIN TIANJIN SHUANGKOU TOWN, BEICHEN CRAFTS FACTORY DISTRICT, TIANJIN CITY, CHINA 天津市静海县利邦工艺制品厂 天津市静海区西翟庄镇西翟庄 天津 天津 2 TIANJIN JINGHAI LEBANG ARTS XIZHAI ZHUANG, JINGHAI COUNTRY 1204ZMC0004 TIANJIN TIANJIN CRAFTS CO.,LTD TIANJIN 天津市宁河县板桥镇田庄坨村外东侧 天津鹏久苇草制品有限公司 天津 天津 THE EAST SIDE OF TIANZHUANGTUO 3 TIANJIN PENGJIU REED PRODUCTS 1200ZMC0012 TIANJIN TIANJIN VILLAGE, BANQIAO TOWN, NINGHE CO.,LTD. COUNTY, TIANJIN, CHINA 河北百年巧匠文化传播股份有限公司 石家庄桥西区新石北路399号 河北 石家庄 4 HEBEI BAINIANQIAOJIANG NO.399, XINSHI NORTH ROAD, QIAOXI 1300ZMC9003 HEBEI SHIJIAZHUANG CULTURE COMMUNICATION INC. DISTRICT, SHIJIAZHUANG CITY 行唐县森旺工贸有限公司 河北省石家庄行唐县口头镇 河北 石家庄 5 XINGTANGXIAN SENWANG KOUTOU TOWN, XINGTANG COUNTY, 1300ZMC0003 HEBEI SHIJIAZHUANG INDUSTRY AND TRADING CO.,LTD SHIJIAZHUANG, HEBEI CHINA 唐山市燕南制锹有限公司 河北省滦南县城东 河北 唐山 6 TANGSHAN YANNAN EAST OF LUANNAN COUNTY, HEBEI, 1302ZMC0002 HEBEI TANGSHAN SHOVEL-MAKING CO.,LTD CHINA 唐山天坤金属工具制造有限公司 河北省唐山市滦南县唐乐公路南侧 河北 唐山 7 TANGSHAN TIANKUN METAL SOUTH OF TANGLE ROAD, LUANNAN 1302ZMC0008 HEBEI TANGSHAN TOOLS MAKING CO.,LTD COUNTY, HEBEI, CHINA 唐山市长智农工具设计制造有限公司 TANGSHAN CHANGZHI 河北省滦南县城东杜土村南 河北 唐山 8 AGRICULTURAL TOOLS SOUTH OF DUTU TOWN, LUANNAN 1302ZMC0031 HEBEI TANGSHAN DESIGNING AND COUNTY, HEBEI, CHINA MANUFACTURING CO.,LTD. 唐山腾飞五金工具制造有限公司 河北省滦南县宋道口镇 河北 唐山 9 TANGSHAN TENGFEI HARDWARE SONG DAO KOU TOWN, LUANNAN 1302ZMC0009 HEBEI TANGSHAN TOOLS MANUFACTURE CO.,LTD. COUNTY, HEBEI CHINA 河北省滦南县宋道口镇杜土村南 唐山舒适五金工具制造有限公司 河北 唐山 SOUTH OF DUTU, SONG DAO KOU 10 TANGSHAN SHUSHI HARDWARE 1302ZMC0040 HEBEI TANGSHAN TOWN, LUANNAN COUNTY, HEBEI TOOLS MANUFACTURE CO,LTD CHINA 唐山腾骥锻轧农具制造有限公司 河北省滦南县宋道口镇 河北 唐山 TANGSHAN TENGJI FORGED 11 SONG DAO KOU TOWN, LUANNAN 1302ZMC0011 HEBEI TANGSHAN AGRICULTURE IMPLEMENTS COUNTY, HEBEI CHINA MANUFACTURING CO.,LTD. -

Cotton on Group Supplier List 2018 Cotton on Group - Supplier List 2

Cotton On Group supplier list 2018 Cotton On Group - Supplier List _2 TOTAL % OF FEMALE % OF MIGRANT/ PARENT COUNTRY FACTORY NAME SUPPLIER ADDRESS STAGE WORKERS WORKERS TEMP COMPANY (IF APPLICABLE) UNIT 4/22 NARABANG WAY AUSTRALIA AXIS TOYS BELROSE CMT 3 67 0 NSW 2085 10 CHALDER STREET AUSTRALIA BODYTREATS AUSTRALIA MARRICKVILLE CMT 3 3 0 NSW 2204 32 CHESTERFIELD AVE BONDI CONSTELLATION PTY LTD MALVERN AUSTRALIA T/A ZEBRA HOMEWARES AND CMT 4 67 0 MELBOURNE SMILING ZEBRA SUITE 6, 60 LANGRIDGE ST AUSTRALIA I SCREAM NAILS COLLINGWOOD CMT VIC 3066 42 BARKLY ST INNOVATIVE BEVERAGE CO PTY AUSTRALIA ST KILDA CMT 7 29 0 LTD VIC 3182 UNIT 1, 57-59 BURCHILL STREET AUSTRALIA LIFESTYLE JEWELLERY PTY LTD LOGANHOLME CMT 20 56 0 QLD 4129 90 MARIBYRNONG CT AUSTRALIA LONELY PLANET FOOTSCRAY CMT VIC 3011 88 KYABRAM ST AUSTRALIA MERCATOR PTY LTD COOLAROO CMT VIC 3048 3/1490 FERNTREE GULLY ROAD AUSTRALIA WARRANBROOKE PTY LTD KNOXFIELD CMT VIC 3180 HARI BARITEK BANGLADESH A&A TROUSERS PUBAIL COLLEGE GATE CMT 1973 61 0 N/A GAZIPUR SINGAIR ROAD, DEKKO ACCESSORIES BANGLADESH AGAMI ACCESSORIES LTD HEMAYETPUR, RAW MATERIALS 324 25 0 LIMITED SAVAR, DHAKA GOLORA, CHORKHONDO, BANGLADESH AKIJ TEXTILE MILLS LTD MANIKGANJ SADAR, FABRIC/MILLS 1904 18 0 AKIJ GROUP MANIKGANJ Supplier List as at June 2018 Cotton On Group - Supplier List _3 BOIRAGIRCHALA BANGLADESH AMANTEX UNIT 2 LTD SREEPUR, INPUTS 74 0 0 N/A GAZIPUR 468-69, BSCIC I/A, SHASHONGAON BANGLADESH AMS KNITWEAR LTD ENAYETNAGAR, FATULLAH CMT 212 83 0 N/A NARAYANGONJ-1400 SATISH ROAD BANGLADESH ANAM CLOTHING LTD -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2016 ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 6, 2016 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 21–471 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:58 Oct 05, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\AR16 NEW\21471.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Cochairman Chairman JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina TOM COTTON, Arkansas TRENT FRANKS, Arizona STEVE DAINES, Montana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois BEN SASSE, Nebraska DIANE BLACK, Tennessee DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio GARY PETERS, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California TED LIEU, California EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS CHRISTOPHER P. LU, Department of Labor SARAH SEWALL, Department of State DANIEL R. RUSSEL, Department of State TOM MALINOWSKI, Department of State PAUL B. PROTIC, Staff Director ELYSE B. ANDERSON, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:58 Oct 05, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\AR16 NEW\21471.TXT DEIDRE C O N T E N T S Page I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 Overview ............................................................................................................ 5 Recommendations to Congress and the Administration .............................. -

Eels Are Needle-Sized the Severn & Wye Smokery (Left)

THE INDEPENDENT THEINDEPENDENT 44/ Food&Drink FRIDAY20 APRIL 2012 FRIDAY20 APRIL 2012 Food&Drink /45 els and Easter arrive togeth- Fishy business: smoked eel from er. The eels are needle-sized the Severn & Wye smokery (left). babies, called elvers or glass Bottom: fishing on the Severn; My life in eels because they’re totally young eels; the smoking process food... transparent, reaching British shores at the end of an ex- in the big tidal rivers, 99 per cent of Hélène hausting 4,000-mile mara- them will die.” thon swim from the Sargas- Richard is even enlisting local schools Darroze Eso Sea where they spawn. and chefs in the recovery effort. Over For generations, the arrival of migra- the next few weeks he will take tanks tory so-called European eels used to be of glass eels into 50 primary schools anxiously awaited at this time of year whose pupils will feed them for around by fishermen on the Severn and Wye 10 weeks until the fish have doubled in tidal rivers. They collected them in nets size. The children will then release them at night then fried them up with bacon into local inland rivers – while sam- and scrambled eggs to make a delicious pling Richard’s smoked eel. Some tanks dish looking like a plate of marine in the Eels in Schools scheme are spon- spaghetti. The tiny glass eels gave it a sored by chefs including Martin Wishart, delicate crunch. Sometimes they were Mitch Tonks and Brian Turner. After working under Alain Ducasse, even mixed with herbs and transformed Some conservationists complain Hélène Darroze opened her own into a “cake”. -

120 China Minzhong Food Corporation Limited

CHINA MINZHONG FOOD CORPORATION LIMITED CORPORATION FOOD MINZHONG CHINA CHINA MINZHONG FOOD CHINA MINZHONG FOOD CORPORATION LIMITED CORPORATION LIMITED (Company Registration Number: 200402715N) National Leading Dragon Head Enterprise 229 Mountbatten Road #02-05 Mountbatten Square Singapore 398007 Tel : (65) 6346 7506 2015 REPORT ANNUAL Fax : (65) 6346 0787 Web : www.chinaminzhong.com Email : [email protected] AN 015 NUAL REPORT 2 CORPORATE INFORMATION Board of Directors Head Office Mr. Lin Guo Rong Sanshan Village, Xitianwei Town (Executive Chairman and Chief Executive Officer) Licheng District, Putian City Mr. Siek Wei Ting Fujian Province (Executive Director and Chief Financial Officer) People’s Republic of China (Postal Code 351131) Mr. Hendra Widjaja (Non-Executive and Non-Independent Director) Solicitors Mr. Kasim Rusmin Rajah & Tann Singapore LLP (Alternate Director to Mr. Hendra Widjaja) 9 Battery Road #25-01 Mr. Goh Kian Chee The Straits Trading Building (Non-Executive and Independent Director) Singapore 049910 Mr. Lim Yeow Hua (Non-Executive and Independent Director) External Auditors Mr. Lim Gee Kiat Crowe Horwath First Trust LLP (Non-Executive and Independent Director) 8 Shenton Way #05-01 AXA Tower Audit Committee Singapore 068811 Mr. Lim Yeow Hua (Chairman) Partner-in-charge: Alfred Cheong Keng Chuan Mr. Hendra Widjaja (Appointed since 2011) Mr. Goh Kian Chee Mr. Lim Gee Kiat Internal Auditors BDO LLP Remuneration Committee 21 Merchant Road #05-01 Mr. Goh Kian Chee (Chairman) Singapore 058267 Mr. Hendra Widjaja Mr. Lim Gee Kiat Partner-in-charge: Koh Chin Beng (Appointed since 2015) Nominating Committee Mr. Goh Kian Chee (Chairman) Principal Bankers Mr. Hendra Widjaja Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Limited Mr. -

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation - Chinese Producers of Wooden Cabinets and Vanities Company Name Company Information Company Name: A Shipping A Shipping Street Address: Room 1102, No. 288 Building No 4., Wuhua Road, Hongkou City: Shanghai Company Name: AA Cabinetry AA Cabinetry Street Address: Fanzhong Road Minzhong Town City: Zhongshan Company Name: Achiever Import and Export Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 103 Taihe Road Gaoming Achiever Import And Export Co., City: Foshan Ltd. Country: PRC Phone: 0757-88828138 Company Name: Adornus Cabinetry Street Address: No.1 Man Xing Road Adornus Cabinetry City: Manshan Town, Lingang District Country: PRC Company Name: Aershin Cabinet Street Address: No.88 Xingyuan Avenue City: Rugao Aershin Cabinet Province/State: Jiangsu Country: PRC Phone: 13801858741 Website: http://www.aershin.com/i14470-m28456.htmIS Company Name: Air Sea Transport Street Address: 10F No. 71, Sung Chiang Road Air Sea Transport City: Taipei Country: Taiwan Company Name: All Ways Forwarding (PRe) Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 268 South Zhongshan Rd. All Ways Forwarding (China) Co., City: Huangpu Ltd. Zip Code: 200010 Country: PRC Company Name: All Ways Logistics International (Asia Pacific) LLC. Street Address: Room 1106, No. 969 South, Zhongshan Road All Ways Logisitcs Asia City: Shanghai Country: PRC Company Name: Allan Street Address: No.188, Fengtai Road City: Hefei Allan Province/State: Anhui Zip Code: 23041 Country: PRC Company Name: Alliance Asia Co Lim Street Address: 2176 Rm100710 F Ho King Ctr No 2 6 Fa Yuen Street Alliance Asia Co Li City: Mongkok Country: PRC Company Name: ALMI Shipping and Logistics Street Address: Room 601 No. -

Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. Huangjindui

产品总称 委托方名称(英) 申请地址(英) Huangjindui Industrial Park, Shanggao County, Yichun City, Jiangxi Province, Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. China Folic acid/D-calcium Pantothenate/Thiamine Mononitrate/Thiamine East of Huangdian Village (West of Tongxingfengan), Kenli Town, Kenli County, Hydrochloride/Riboflavin/Beta Alanine/Pyridoxine Xinfa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Dongying City, Shandong Province, 257500, China Hydrochloride/Sucralose/Dexpanthenol LMZ Herbal Toothpaste Liuzhou LMZ Co.,Ltd. No.282 Donghuan Road,Liuzhou City,Guangxi,China Flavor/Seasoning Hubei Handyware Food Biotech Co.,Ltd. 6 Dongdi Road, Xiantao City, Hubei Province, China SODIUM CARBOXYMETHYL CELLULOSE(CMC) ANQIU EAGLE CELLULOSE CO., LTD Xinbingmaying Village, Linghe Town, Anqiu City, Weifang City, Shandong Province No. 569, Yingerle Road, Economic Development Zone, Qingyun County, Dezhou, biscuit Shandong Yingerle Hwa Tai Food Industry Co., Ltd Shandong, China (Mainland) Maltose, Malt Extract, Dry Malt Extract, Barley Extract Guangzhou Heliyuan Foodstuff Co.,LTD Mache Village, Shitan Town, Zengcheng, Guangzhou,Guangdong,China No.3, Xinxing Road, Wuqing Development Area, Tianjin Hi-tech Industrial Park, Non-Dairy Whip Topping\PREMIX Rich Bakery Products(Tianjin)Co.,Ltd. Tianjin, China. Edible oils and fats / Filling of foods/Milk Beverages TIANJIN YOSHIYOSHI FOOD CO., LTD. No. 52 Bohai Road, TEDA, Tianjin, China Solid beverage/Milk tea mate(Non dairy creamer)/Flavored 2nd phase of Diqiuhuanpo, Economic Development Zone, Deqing County, Huzhou Zhejiang Qiyiniao Biological Technology Co., Ltd. concentrated beverage/ Fruit jam/Bubble jam City, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China Solid beverage/Flavored concentrated beverage/Concentrated juice/ Hangzhou Jiahe Food Co.,Ltd No.5 Yaojia Road Gouzhuang Liangzhu Street Yuhang District Hangzhou Fruit Jam Production of Hydrolyzed Vegetable Protein Powder/Caramel Color/Red Fermented Rice Powder/Monascus Red Color/Monascus Yellow Shandong Zhonghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd. -

The Flavor of Edo Spans the Globe -The Food of Edo Becomes a Food

The Flavor of Edo Spans the Globe The Food of Edo Becomes a Food of the World Zenjiro Watanabe Many readers were surprised by the article, "A Comparison of Mr. Watanabe was born in Tokyo in the Cultural Levels of Japan and Europe," presented in FOOD 1932 and graduated from Waseda University in 1956. In 1961, he received CULTURE No. 6. The widely held presumption that the average his Ph.D in commerce from the same lifestyle of the Edo era was dominated by harsh taxation, university and began working at the National Diet Library. Mr. Watanabe oppression by the ruling shogunate, and a general lack of worked at the National Diet Library as freedom was destroyed. The article in FOOD CULTURE No. 6 manager of the department that referred to critiques made by Europeans visiting Japan during researches the law as it applies to agriculture. He then worked as the Edo era, who described the country at that time in exactly manager of the department that opposite terms. These Europeans seem to have been highly researches foreign affairs, and finally he devoted himself to research at the Library. Mr. Watanabe retired in 1991 impressed by the advanced culture and society they found in and is now head of a history laboratory researching various aspects of Japan, placing Japan on a level equal with Europe. In this cities, farms and villages. edition we will discuss the food culture of the Edo era, focusing Mr. Watanabe’s major works include Toshi to Noson no Aida—Toshikinko Nogyo Shiron, 1983, Ronsosha; Kikigaki •Tokyo no Shokuji, edited 1987, primarily on the city of Edo itself. -

Simply Cooked LEMON CAPER • TAMARIND BROWN BUTTER HEARTS of PALM CRAB CAKE 21 JICAMA-MANGO SLAW, PIPIAN SAUCE (V)

Raw Bar COLD SEAFOOD TOWERS* SMALL 99 / LARGE 159 TORO TARTARE 39 CHEF’S SELECTION OF LOBSTER, KING CRAB, SHRIMP CAVIAR, WASABI, SOY OYSTERS, CLAMS, MUSSELS, CEVICHE (GF) SPINACH ARTICHOKE SALAD 23 CRISPY SHITAKE, DRY RED MISO, CRISPY LEEK, T OYSTER SHOOTERS 12/30 (1PC/3PCS) RUFFLE-YUZU VINAIGRETTE, PARMESAN TEQUILA CUCUMBER OR SPICY BLOODY MARY ROASTED BEETS 16 OYSTERS MP 1/2 DZ OR DOZEN TRI-COLORED BEETS, GOAT CHEESE FOAM, CANDIED WALNUTS, ARUGULA SALAD ASK SERVER FOR DAILY SELECTION (GF) (GF, VEGAN UPON REQUEST) JUMBO SHRIMP 24/3PCS (GF) BABY GEM CAESAR SALAD 21 SUGAR SNAP PEAS, ASPARAGUS, AVOCADO, SUNFLOWER SEEDS, LEMON PARMESAN VINAIGRETTE (VEGAN UPON REQUEST) TRUFFLE SASHIMI 35 TARTARE TRIO 33 TUNA, HAMACHI, CHILI PONZU Signature cold SALMON, HAMACHI, TUNA, TOBIKO CAVIAR, BLACK TRUFFLE PURÉE WASABI CREME FRAICHE A5 MIYAZAKI WAYGU BEEF TARTARE 28 SESAME SEARED KING SALMON 25 SALMON BELLY CARPACCIO 27 TRUFFLE PONZU, CAVIAR, SUSHI RICE ALASKAN KING SALMON, YUZU SOY, HOT SESAME OLIVE OIL WATERCRESS, SWEET & SOUR ONION, YUZU CUCUMBER WRAP (DF) TOASTED SESAME SEEDS, GINGER, CHIVES MRC ROLL 21 ROLLed VEGETABLE KING ROLL 17 SEARED TUNA, SHRIMP, AVOCADO KING OYSTER MUSHROOM, CASHEW, SPICY MISO PONZU BROWN BUTTER CATCH ROLL 21 (ADDITIONAL VEGAN VARIATIONS UPON REQUEST) CRAB, SALMON, MISO-HONEY HELLFIRE ROLL 21 LOBSTER AVOCADO ROLL 24 SPICY TUNA TWO-WAYS, PEAR, BALSAMIC BROWN RICE OR CUCUMBER WRAP AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST KING CRAB, CUCUMBER, MANGO SALSA Hand Roll Cut Roll Nigiri Sashimi EEL AVOCADO 14 // 16 YELLOWTAIL AVOCADO* 11 // 14 FLUKE -

Evacuation Priority Method in Tsunami Hazard Based on DMSP/OLS Population Mapping in the Pearl River Estuary, China

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Evacuation Priority Method in Tsunami Hazard Based on DMSP/OLS Population Mapping in the Pearl River Estuary, China Bahaa Mohamadi 1,2 , Shuisen Chen 1,* and Jia Liu 1 1 Guangdong Open Laboratory of Geospatial Information Technology and Application, Guangdong Engineering Technology Center for Remote Sensing Big Data Application, Guangdong Key Laboratory of Remote Sensing and GIS Technology Application, Guangzhou Institute of Geography, Guangzhou 510070, China; [email protected] (B.M.); [email protected] (J.L.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Information Engineering in Surveying, Mapping and Remote Sensing, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430079, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-20-876-855-13 Received: 9 January 2019; Accepted: 4 March 2019; Published: 9 March 2019 Abstract: Evacuation plans are critical in case of natural disaster to save people’s lives. The priority of population evacuation on coastal areas could be useful to reduce the death toll in case of tsunami hazard. In this study, the population density remote sensing mapping approach was developed using population records in 2013 and Defense Meteorological Satellite Program’s Operational Linescan System (DMSP/OLS) night-time light (NTL) image of the same year for defining the coastal densest resident areas in Pearl River Estuary (PRE), China. Two pixel-based saturation correction methods were evaluated for application of population density mapping to enhance DMSP/OLS NTL image. The Vegetation Adjusted NTL Urban Index (VANUI) correction method (R2 (original/corrected): 0.504, Std. error: 0.0069) was found to be the better-fit correction method of NTL image saturation for the study area compared to Human Settlement Index (HSI) correction method (R2 (original/corrected): 0.219, Std. -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

The Transnational World of Chinese Entrepreneurs in Chicago, 1870S to 1940S: New Sources and Perspectives on Southern Chinese Emigration

Front. Hist. China 2011, 6(3): 370–406 DOI 10.1007/s11462-011-0134-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Huping Ling The Transnational World of Chinese Entrepreneurs in Chicago, 1870s to 1940s: New Sources and Perspectives on Southern Chinese Emigration 树挪死,人挪活 A tree would likely die when transplanted; a man will survive and thrive when migrated. —Chinese proverb (author’s translation) © Higher Education Press and Springer-Verlag 2011 Abstract This article contributes to an ongoing dialogue on the causes of migration and emigration and the relationship between migrants/emigrants and their homelands by investigating historical materials dealing with the Chinese in Chicago from 1870s to 1940s. It shows that patterns of Chinese migration/ emigration overseas have endured for a long period, from pre-Qing times to today’s global capitalist expansionism. The key argument is that from the very beginning of these patterns, it has been trans-local and transnational connections that have acted as primary vehicles facilitating survival in the new land. While adjusting their lives in new environments, migrants and emigrants have made conscious efforts to maintain and renew socioeconomic and emotional ties with their homelands, thus creating transnational ethnic experiences. Keywords Chinese migration and emigration, overseas Chinese, Chinese in Chicago, Chinese ethnic businesses Introduction Just as all early civilizations used migration as an important survival strategy, so too Chinese migrated in great numbers. For example, beginning even as early as Huping Ling