1 Chapter I Introduction, Review of Literature And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Farmer Database

KVK, Trichy - Farmer Database Animal Biofertilier/v Gende Commun Value Mushroo Other S.No Name Fathers name Village Block District Age Contact No Area C1 C2 C3 Husbandry / Honey bee Fish/IFS ermi/organic Others r ity addition m Enterprise IFS farming 1 Subbaiyah Samigounden Kolakudi Thottiyam TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 57 9787932248 BC 2 Manivannan Ekambaram Salaimedu, Kurichi Kulithalai Karur M 58 9787935454 BC 4 Ixora coconut CLUSTERB 3 Duraisamy Venkatasamy Kolakudi Thottiam TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787936175 BC Vegetable groundnut cotton EAN 4 Vairamoorthy Aynan Kurichi Kulithalai Karur M 33 9787936969 bc jasmine ixora 5 subramanian natesan Sirupathur MANACHANALLUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787942777 BC Millet 6 Subramaniyan Thirupatur MANACHANALLUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787943055 BC Tapioca 7 Saravanadevi Murugan Keelakalkandarkottai THIRUVERAMBUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI F 42 9787948480 SC 8 Natarajan Perumal Kattukottagai UPPILIYAPURAM TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 47 9787960188 BC Coleus 9 Jayanthi Kalimuthu top senkattupatti UPPILIYAPURAM Tiruchirappalli F 41 9787960472 ST 10 Selvam Arunachalam P.K.Agaram Pullampady TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 23 9787964012 MBC Onion 11 Dharmarajan Chellappan Peramangalam LALGUDI TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 68 9787969108 BC sugarcane 12 Sabayarani Lusis prakash Chinthamani Musiri Tiruchirappalli F 49 9788043676 BC Alagiyamanavala 13 Venkataraman alankudimahajanam LALGUDI TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 67 9788046811 BC sugarcane n 14 Vijayababu andhanallur andhanallur TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 30 9788055993 BC 15 Palanivel Thuvakudi THIRUVERAMBUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 65 9788056444 -

List of the Panchayats and Different Villages Adopted by Holy Cross College

List of the Panchayats and different villages adopted by Holy Cross College HOLY CROSS COLLEGE (Autonomous), Tiruchirappalli-2 RESCAPES PANCHAYAT NAME VILLAGE NAME 1. AZHAGIYAMANVALAM 2. GOPURAPATTY 1. AZHAGIYAMANVALAM 3. PALAIYUR 4. THIRUVARANGAPATTY 5. KOVATHAKUDI 2. KOVATHAKUDI 6. PAACHUR 7. SALAPATTY-NORTH 3. SIRUPATHUR 8. VEERANI 4. THIRUVASI 9. THIRUVASI 10. THATHAMANGALAM 5. THATHAMANGALAM 11. DEVIMANGALAM 12. NO.94 KARIYAMANIKAM 6. NO.94 KARIYAMANIKAM 13. KANNIYAKUDI 14. C.AYAMPALAYAM 7. C.AYAMPALAYAM 15. SALAKADU-SOUTH 16. THIRUPANJALEE 8. THIRUPANJALEE 17. VALMANAPALAYAM-MELUR 18. VALMANAPALAYAM-KELUR 19. SENGUDI 9. NO-2 KARIYAMANIKAM 20. SENNAKARAI 21. KURUVAMPATTY 10. THALUTHALAPATTY 22. THALUTHALAPATTY 11. AYIKUDI 23. AYIKUDI 12. VALAIYUR 24. VALAIYUR Map of the adopted Panchayats at Manachanallur Block at Tiruchirappalli in Tamil Nadu, India HOLY CROSS COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS), Tiruchirappalli- 620 002 Part VI - SERVICE ORIENTED COURSES Staff in Charge List Extension Activities Staff In charge Shift I Shift II AICUF Dr. Pricila, R. Ms. Mercy Jennifer.M.D Come Alive Program Dr. Crescenta Shakila Motha.L Ms. V.Jayarani Consumer Club Dr. Josephine Lourdu De Rose R.Aishwarya Financial Literacy Club Ms.Mary Suthanthiramalar, M. Ms. N. Jayalakshmi Ms. Arockia Punitha.S EXNORA Dr. Janova Mary Ms. Vidhya.N NCC Ms. Arockia Saibe.P NSS Dr. Shanthi, P. Ms. Nobel Ester Ms. A. RoselineMary Red Ribbon Club Ms. Suregka Felix, K. Ms. Jeba Synthia. D.M Rotaract Dr. Morris Princy Ms. Angel Metilda. G Dr. Antonitte Vinolini.L Gender champion club Ms. Saraswathi, R. Ms. Deerkalakshmi Ms. Mary Elizabeth Shayamala Ms. Irudaya Monica Catherine .J Youth Red Cross Dr. Suganthi, K. Ms. Tony Elizabeth.A Leo club Ms. -

Trichirapalli.Pdf

Contents TITLE Page No. Message by Member Secretary, State Planning Commission i Preface by the District Collector iii Acknowledgement v List of Boxes vii List of Figures viii List of Tables ix Chapters 1. DistrictProfile 1 2. Status of Human Development 11 3. Employment, Income and Poverty 29 4. Demography, Health and Nutrition 45 5. Literacy and Education 75 6. Gender 105 7. Social Security 113 8. Infrastructure 123 9. Summary and Way Forward 133 Annexures Technical Notes A20 Abbreviations A27 References A29 TIRUCHIRAPPALI DISTRICT HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2017 District Administration, Tiruchirappali and State Planning Commission, Tamil Nadu in association with Bharathidasan University Contents TITLE Page No. Message by Member Secretary, State Planning Commission i Preface by the District Collector iii Acknowledgement v List of Boxes vii List of Figures viii List of Tables ix Chapters 1. DistrictProfile 1 2. Status of Human Development 11 3. Employment, Income and Poverty 29 4. Demography, Health and Nutrition 45 5. Literacy and Education 75 6. Gender 105 7. Social Security 113 8. Infrastructure 123 9. Summary and Way Forward 133 Annexures Technical Notes A20 Abbreviations A27 References A29 Dr. K.S.Palanisamy,I.A.S., Office : 0431-2415358 District Collector, Fax : 0431-2411929 Tiruchirappalli. Res : 0431-2420681 0431-2420181 Preface India has the potential to achieve and the means to secure a reasonable standard of living for all the sections of its population. Though the economy touched the nine per cent growth rate during the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-12), there are socio-economically disadvantaged people who are yet to benefit from this growth. -

Thiruchirappal Disaster Managem Iruchirappalli

Tiruchirappalli District Disaster Management Plan – 2020 THIRUCHIRAPPALLI DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN-2020 Tiruchirappalli District Disaster Management Plan – 2020 INDEX S. Particulars Page No. No. 1. Introduction 1 2. District Profile 2-4 3. Disaster Management Goals (2017-2030) 5-11 4. Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Analysis with Maps 12-49 (District map, Division maps, Taluk maps & list of Vulnerable area) 5. Institutional Mechanism 50-52 6. Preparedness Measures 53-56 7. Prevention and Mitigation measures (2015 – 2030) 57-58 8. Response Plan 59 9. Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 60-61 10. Mainstreaming Disaster Management in Development Plans 62-63 11. Community and other Stake holder participation 64-65 12. Linkages / Co-ordination with other agencies for Disaster Management 66 13. Budget and Other Financial allocation – Outlays of major schemes 67 14. Monitoring and Evaluation 68 15. Risk Communication Strategies 69-70 16. Important Contact Numbers and provision for link to detailed information 71-108 (All Line Department, BDO, EO, VAO’s) 17. Dos and Don’ts during all possible Hazards 109-115 18. Important Government Orders 116-117 19. Linkages with Indian Disaster Resource Network 118 20 Vulnerable Groups details 118 21. Mock Drill Schedules 119 22. Date of approval of DDMP by DDMA 120 23. Annexure 1 – 14 120-148 Tiruchirappalli District Disaster Management Plan – 2020 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS S. Abbreviation Explanation No. 1. AO Agriculture Officer 2 AF Armed Forces 3 BDO Block Development Officers 4 DDMA District Disaster Management Authority 5 DDMP District Disaster Management Plan 6 DEOC District Emergency Operations Center 7 DRR Disaster Risk Reduction 8 DERAC District Emergency Relief Advisory Committee. -

Executive Summary Book TRICHIRAPALLI.Pmd

THIRUCHIRAPALLI DISTRICT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY DISTRICT HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT TRICHIRAPALLI DISTRICT Introduction The district of Tiruchirappalli was formerly called by the British as ‘Trichinopoly’ and is commonly known as ‘Tiruchirappalli’ in Tamil or Tiruchirappalli‘ in English. The district in its present size was formed in September 1995 by trifurcating the composite Tiruchirappalli district into Tiruchirappalli, Karur and Perambalur districts. The district is basically agrarian; the industrial growth has been supported by the public sector companies like BHEL, HAPP, OFT and Railway workshop. The district is pioneer in fabrication industry and the front runner in the fabrication of windmill towers in the country. As two rivers flow through the district, the Northern part of the district is filled with greeneries than other areas of the district. The river Cauvery irrigates about 51,000 ha. in Tiruchirappalli, Lalgudi and Musiri Divisions. Multifarious crops are grown in this district and Agriculture is the main occupation for most of the people in the District. With an area of 36,246 hectares under the coverage of the forests the district accounts for 1.65 percentage of the total forest area of 1 the State. Honey and Cashewnuts are the main forest produces besides fuel wood. The rivers Kaveri (also called Cauvery) and the river Coleroon (also called Kollidam) flow through the district. There are a few reserve forests along the river Cauvery, located at the west and the north-west of the city. Tiruchirappalli district has been divided into three revenue divisions, viz., Tiruchirappalli, Musiri and Lalgudi. It is further classified into 14 blocks, viz., Andanallur, Lalgudi, Mannachanallur, Manigandam, Manapparai, Marungapuri, Musiri, Pullambadi, Thiruvarumbur, Thottiyam, Thuraiyur, T.Pet, Uppiliyapuram, and Vaiyampatti. -

Tiruchirappalli Underground Sewerage System

Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 49107-004 May 2018 IND: Tamil Nadu Urban Flagship Investment Program – Tiruchirappalli Underground Sewerage System Prepared by Tiruchirappalli City Corporation of Government of Tamil Nadu for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 11 May 2018) Currency Unit – Indian rupee (₹) ₹1.00 – $0.015 $1.00 = ₹67.09 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ASI – Archaeological Survey of India CMSC – construction management and supervision consultant CPCB – Central Pollution Control Board CTE – consent to establish CTO – consent to operate EAC – expert appraisal committee EHS – environmental, health and safety EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan ESS – environmental and social safeguards ESZ – eco sensitive zone GRC – grievance redress committee GRM – grievance redress mechanism GOTN – Government of Tamil Nadu IEE – initial environmental examination MOEFCC – Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change NOC – no objection certificate PIU – project implementation unit PMU – project management unit ROW – right-of-way SIDCO – Small Industries Development Corporation SPS – Safeguard Policy Statement STP – sewage treatment plant TCC – Tiruchirappalli City Corporation TNPCB – Tamil Nadu Pollution Control Board TNUFIP – Tamil Nadu Urban Flagship Investment Program TNUIFSL – Tamil Nadu Urban Infrastructure Financial Services Limited TWADB – Tamil Nadu Water and Drainage Board ULB – urban local body WHO – World Health Organization WTP – water treatment plant WEIGHTS AND MEASURES C degree Celsius km kilometer lpcd litre per capita per day m meter ml milliliter Mld million liters per day mm millimeter km2 square kilometer NOTE In this report, "$" refers to United States dollars. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

Dos-Fsos -District Wise List

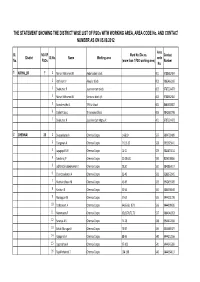

THE STATEMENT SHOWING THE DISTRICT WISE LIST OF FSOs WITH WORKING AREA, AREA CODE No. AND CONTACT NUMBER AS ON 05.09.2012 Area Sl. NO.OF Ward No./Div.no. Contact District Sl.No. Name Working area code No. FSOs (more than 1 FSO working area) Number No. 1 ARIYALUR 7 1 Nainar Mohamed.M Andimadam block 001 9788682404 2 Rathinam.V Ariyalur block 002 9865463269 3 Sivakumar.P Jayankondam block 003 9787224473 4 Nainar Mohamed.M Sendurai block i/c 004 9788682404 5 Savadamuthu.S T.Palur block 005 8681920807 6 Stalin Prabu.L Thirumanur block 006 9842387798 7 Sivakumar.P Jayankondam Mpty i/c 401 9787224473 2 CHENNAI 25 1 Sivasankaran.A Chennai Corpn. 1-6&10 527 9894728409 2 Elangovan.A Chennai Corpn. 7-9,11-13 528 9952925641 3 Jayagopal.N.H Chennai Corpn. 14-21 529 9841453114 4 Sundarraj.P Chennai Corpn. 22-28 &31 530 8056198866 5 JebharajShobanaKumar.K Chennai Corpn. 29,30 531 9840867617 6 Chandrasekaran.A Chennai Corpn. 32-40 532 9283372045 7 Muthukrishnan.M Chennai Corpn. 41-49 533 9942495309 8 Kasthuri.K Chennai Corpn. 50-56 534 9865390140 9 Mariappan.M Chennai Corpn. 57-63 535 9444231720 10 Sathasivam.A Chennai Corpn. 64,66-68 &71 536 9444909695 11 Manimaran.P Chennai Corpn. 65,69,70,72,73 537 9884048353 12 Saranya.A.S Chennai Corpn. 74-78 538 9944422060 13 Sakthi Murugan.K Chennai Corpn. 79-87 539 9445489477 14 Rajapandi.A Chennai Corpn. 88-96 540 9444212556 15 Loganathan.K Chennai Corpn. 97-103 541 9444245359 16 RajaMohamed.T Chennai Corpn. -

List of Food Safety Officers

LIST OF FOOD SAFETY OFFICER State S.No Name of Food Safety Area of Operation Address Contact No. Email address Officer /District ANDAMAN & 1. Smti. Sangeeta Naseem South Andaman District Food Safety Office, 09434274484 [email protected] NICOBAR District Directorate of Health Service, G. m ISLANDS B. Pant Road, Port Blair-744101 2. Smti. K. Sahaya Baby South Andaman -do- 09474213356 [email protected] District 3. Shri. A. Khalid South Andaman -do- 09474238383 [email protected] District 4. Shri. R. V. Murugaraj South Andaman -do- 09434266560 [email protected] District m 5. Shri. Tahseen Ali South Andaman -do- 09474288888 [email protected] District 6. Shri. Abdul Shahid South Andaman -do- 09434288608 [email protected] District 7. Smti. Kusum Rai South Andaman -do- 09434271940 [email protected] District 8. Smti. S. Nisha South Andaman -do- 09434269494 [email protected] District 9. Shri. S. S. Santhosh South Andaman -do- 09474272373 [email protected] District 10. Smti. N. Rekha South Andaman -do- 09434267055 [email protected] District 11. Shri. NagoorMeeran North & Middle District Food Safety Unit, 09434260017 [email protected] Andaman District Lucknow, Mayabunder-744204 12. Shri. Abdul Aziz North & Middle -do- 09434299786 [email protected] Andaman District 13. Shri. K. Kumar North & Middle -do- 09434296087 kkumarbudha68@gmail. Andaman District com 14. Smti. Sareena Nadeem Nicobar District District Food Safety Unit, Office 09434288913 [email protected] of the Deputy Commissioner , m Car Nicobar ANDHRA 1. G.Prabhakara Rao, Division-I, O/o The Gazetted Food 7659045567 [email protected] PRDESH Food Safety Officer Srikakulam District Inspector, Kalinga Road, 2. K.Kurmanayakulu, Division-II, Srikakulam District, 7659045567 [email protected] LIST OF FOOD SAFETY OFFICER State S.No Name of Food Safety Area of Operation Address Contact No. -

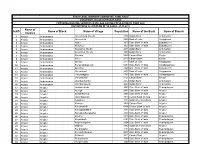

S.NO Name of District Name of Block Name of Village Population Name

STATE LEVEL BANKERS' COMMITTEE, TAMIL NADU CONVENOR: INDIAN OVERSEAS BANK PROVIDING BANKING SERVICES IN VILLAGE HAVING POPULATION OF OVER 2000 DISTRICTWISE ALLOCATION OF VILLAGES -01.11.2011 Name of S.NO Name of Block Name of Village Population Name of the Bank Name of Branch District 1 Ariyalur Andiamadam Anikudichan (South) 2730 Indian Bank Andimadam 2 Ariyalur Andiamadam Athukurichi 5540 Bank of India Alagapuram 3 Ariyalur Andiamadam Ayyur 3619 State Bank of India Edayakurichi 4 Ariyalur Andiamadam Kodukkur 3023 State Bank of India Edayakurichi 5 Ariyalur Andiamadam Koovathur (North) 2491 Indian Bank Andimadam 6 Ariyalur Andiamadam Koovathur (South) 3909 Indian Bank Andimadam 7 Ariyalur Andiamadam Marudur 5520 Canara Bank Elaiyur 8 Ariyalur Andiamadam Melur 2318 Canara Bank Elaiyur 9 Ariyalur Andiamadam Olaiyur 2717 Bank of India Alagapuram 10 Ariyalur Andiamadam Periakrishnapuram 5053 State Bank of India Varadarajanpet 11 Ariyalur Andiamadam Silumbur 2660 State Bank of India Edayakurichi 12 Ariyalur Andiamadam Siluvaicheri 2277 Bank of India Alagapuram 13 Ariyalur Andiamadam Thirukalappur 4785 State Bank of India Varadarajanpet 14 Ariyalur Andiamadam Variyankaval 4125 Canara Bank Elaiyur 15 Ariyalur Andiamadam Vilandai (North) 2012 Indian Bank Andimadam 16 Ariyalur Andiamadam Vilandai (South) 9663 Indian Bank Andimadam 17 Ariyalur Ariyalur Andipattakadu 3083 State Bank of India Reddipalayam 18 Ariyalur Ariyalur Arungal 2868 State Bank of India Ariyalur 19 Ariyalur Ariyalur Edayathankudi 2008 State Bank of India Ariyalur 20 Ariyalur -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2018 [Price : Rs. 8.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 33] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 15, 2018 Aadi 30 , Vilambi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu – 2049 Part VI—Section 1 Notifications of interest to the General Public issued by Heads of Departments, Etc. NOTIFICATIONS BY HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS, ETC. CONTENTS PPages.ages. GENERAL NOTIFICATIONS Preparation and Sanction of the Arappanancheri Detailed Development Plan No. 4 of Kancheepuram Local Planning Authority. .. .. .. .. .. .. 226868 Variation to the Approved Master Plan for the Kancheepuram Local Planning Area. .. 2268-26968-269 Variations to the Approved Master Plan for the Coimbatore Local Planning Area. .. 227070 DIRECTOR OF SUGAR AND CANE COMMISSIONER, CHENNAI Demarcation of the sugarcane areas among Bannari Amman Sugars Ltd, Kolundampattu, Tiruvannamalai District, Tirupattur Co-operative Sugar Mills Ltd., Kethandapatti, Vellore District, Kallakurichi-I Co-operative Sugar Mill Ltd., Moongilthuraipattu, Villupuram District and Subramaniya Siva Co-operative Sugar Mills Ltd., Gobalapuram, Dharmapuri District as per the Orders of the Hon'ble High Court of Madras in W.A.No.401/1998, etc. - Recommendations of the 49th Area Delimitation Committee meeting held on 19-01-2018, etc. .. 2270-27270-272 JUDICIAL NOTIFICATIONS Code of Criminal Procedure–Conferment of powers .. .. .. .. .. 2272-27672-276 HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF FOOD SAFETY AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION Areas Notifi ed by the Commissioner of Food Safety for the Purpose of Performing duties under the Food Safety and Standards Act Rules and Regulations. .. .. .. 2276-28776-287 DTP—VI-1 (33)—1 267 268 TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE [Part VI—Sec.1 NOTIFICATIONS BY HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS, ETC. -

Sree Saraswathi Thyagaraja College

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ARTS, SCIENCE AND HUMANITIES (A Peer-Reviewed-Refereed/Scholarly Quarterly Journal Globally Indexed with Impact Factor) Vol. 5 Special Issue 4 March, 2018 Impact Factor: 2.114 ISSN: 2321-788X UGC Approval No: 43960 Two Day National Seminar on GENDER DISCRIMINATION AND VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN ISSUES AND CONCERNS 23rd & 24th March 2018 Sponsored by NATIONAL COMMISSION FOR WOMEN New Delhi Organised by PG & RESEARCH DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL WORK SREE SARASWATHI THYAGARAJA COLLEGE An Antonomous NAAC Re – Accredited with ‘A’ Grade, ISO 9001: Certified Institution, Affiliated to Bharathiar University, Coimbatore, Approved by AICTE of MBA/MCA and by UGC for 2(f) & 12(B) Status Pollachi – 642 107, Coimbatore Dist, Tamil Nadu Ln.T.Sethupati Secretary Sree Saraswathi Thyagaraja College (Autonomous) Pollachi, Tamilnadu Social Work practice is quite distinctive from other professions in its approach of assisting clients to function optimally within their environments. Women in India face lots of social issues and problems all through the life which are big challenge and struggle for them right from cradle to grave. Female infanticide is the most common practice of killing girl child in mother’s womb in the rural Indian society. Women in India are considered as burden for their parents and husbands as they think that women are here only to spend and consume money in whole of their life without their share and contribution. Another common problem for women is sex discrimination which they face from their birth and continues till their death. Illiteracy, lack of proper education, house cares, rape, sexual harassment at workplace, etc are some of the other big issues for the women in India. -

Assessment of Ground Water Quality in Kailasapuram, Tiruchirappalli,Tamil Nadu, India

Available online a twww.scholarsresearchlibrary.com Scholars Research Library Archives of Applied Science Research, 2015, 7 (7): 12-18 (http://scholarsresearchlibrary.com/archive.html ) ISSN 0975-508X CODEN (USA) AASRC9 Assessment of ground water quality in Kailasapuram, Tiruchirappalli,Tamil Nadu, India G. Maheswari Devi and S. Umamaheswari* P.G and Research Department of Zoology, Periyar EVR College, Tiruchirappalli, Tamil Nadu, India ____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Cauvery river is the lifeline of the population residing in Tiruchirappalli district. They are dependent on ground water as their prime source of drinking water. Hence, monitoring the quality of ground water is necessary in order to provide the public with potable water. This paper reports the physiochemical parameters of bore and well water at the site exposed to treated waste water from industries. The mean pH, TS, TDS, TSS, TH, Calcium, Alkalinity, Acidity, Total Nitrogen and Sodium and Mercury of well water exceeded the permissible limits of TNPCB. On the other hand, mean pH, TS, TDS, TSS,TH, Ca, alkalinity, acidity, Total Nitrogen and Sodium were found to be above the permissible limits of TNPCB. These could be attributed to seepage of treated industrial waste water into the ground water. Key words : Physicochemical parameters, Water quality, groundwater, treated industrial waste water. __________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The efflux of industrial waste water into the environment may adversely affect the ground water quality. Ground water is used for irrigation, industries and domestic supply. In Tiruchirappalli district, majority of the population depend on the ground water as their prime source of drinking water supply. Rapid growth of urban areas have affected the ground water quality, due to over exploitation of resources and improper waste disposal [1].