Memory of the Voiceless. Verbatim, Cvasi-Verbatim, Mockumentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Hare's Stuff Happens a Dramatic Journey of American War

International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences Submitted: 2015-12-31 ISSN: 2300-2697, Vol. 67, pp 57-69 Accepted: 2016-02-16 doi:10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILSHS.67.57 Online: 2016-03-04 CC BY 4.0. Published by SciPress Ltd, Switzerland, 2016 David Hare’s Stuff Happens A Dramatic Journey of American War on Iraq Elaff Ganim Salih1, Hardev Kaur2, Mohamad Fleih Hassan3 Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 1*[email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Keywords: Verbatim theatre; Stuff Happens; Orientalism; David Hare. ABSTRACT The war launched by America and its allies against the country of Iraq on 2003 was a debatable and notorious war for the public opinion was shocked with the realization that the reasons for launching the war under the title ‘Iraq’s Mass Destruction Weapons’ were false. The tragic consequences of this war led many writers around the world to question the policy of the United States and its manipulation of facts to justify their narratives. The present study examines the American policy of invading Iraq in David Hare’s Stuff Happens. It investigates Hare’s technique of combining documentary realism with imaginative reconstruction of the arguments to dramatize the American Invasion of Iraq. Stuff Happens is a historical and political play written as a verbatim theatre. It depicts the backroom deals and political maneuvers of the Bush administration in justifying their campaign against the ‘Axis of Evil’ culminated by the war against Iraq. The verbatim theatre is the best way of showing the gap between ‘what is said and what is seen to be done’. -

History As a Construct.Pdf

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature English Language and Literature HISTORY AS A CONSTRUCT: CARYL CHURCHILL’S MAD FOREST, DAVID EDGAR’S PENTECOST, AND DAVID HARE’S STUFF HAPPENS Ömer Kemal GÜLTEKİN Ph.D. Dissertation Ankara, 2018 History as a Construct: Caryl Churchill’s Mad Forest, David Edgar’s Pentecost, and David Hare’s Stuff Happens Ömer Kemal GÜLTEKİN Hacettepe University School of Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature English Language and Literature Ph.D. Dissertation Ankara, 2018 BİLDİRİM Hazırladığım tezin/raporun tamamen kendi çalışmam olduğunu ve her alıntıya kaynak gösterdiğimi taahhüt eder, tezimin/raporumun kağıt ve elektronik kopyalarının Hacettepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü arşivlerinde aşağıda belirttiğim koşullarda saklanmasına izin verdiğimi onaylarım: o Tezimin/Raporumun tamamı her yerden erişime açılabilir. o Tezim/Raporum sadece Hacettepe Üniversitesi yerleşkelerinden erişime açılabilir. o Tezimin/Raporumun …… yıl süreyle erişime açılmasını istemiyorum. Bu sürenin sonunda uzatma için başvuruda bulunmadığım takdirde, tezimin/raporumun tamamı her yerden erişime açılabilir. [25.01.2018] [Ömer Kemal Gültekin] YAYIMLAMA VE FİKRİ MÜLKİYET HAKLARI BEYANI Enstitü tarafından onaylanan lisansüstü tezimin/raporumun tamamını veya herhangi bir kısmını, basılı (kâğıt) ve elektronik formatta arşivleme ve aşağıda verilen koşullarla kullanıma açma iznini Hacettepe Üniversitesine verdiğimi bildiririm. Bu izinle Üniversiteye verilen -

Announcing a VIEW from the BRIDGE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE “One of the most powerful productions of a Miller play I have ever seen. By the end you feel both emotionally drained and unexpectedly elated — the classic hallmark of a great production.” - The Daily Telegraph “To say visionary director Ivo van Hove’s production is the best show in the West End is like saying Stonehenge is the current best rock arrangement in Wiltshire; it almost feels silly to compare this pure, primal, colossal thing with anything else on the West End. A guileless granite pillar of muscle and instinct, Mark Strong’s stupendous Eddie is a force of nature.” - Time Out “Intense and adventurous. One of the great theatrical productions of the decade.” -The London Times DIRECT FROM TWO SOLD-OUT ENGAGEMENTS IN LONDON YOUNG VIC’S OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING PRODUCTION OF ARTHUR MILLER’S “A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE” Directed by IVO VAN HOVE STARRING MARK STRONG, NICOLA WALKER, PHOEBE FOX, EMUN ELLIOTT, MICHAEL GOULD IS COMING TO BROADWAY THIS FALL PREVIEWS BEGIN WEDNESDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 21 OPENING NIGHT IS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE Direct from two completely sold-out engagements in London, producers Scott Rudin and Lincoln Center Theater will bring the Young Vic’s critically-acclaimed production of Arthur Miller’s A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE to Broadway this fall. The production, which swept the 2015 Olivier Awards — winning for Best Revival, Best Director, and Best Actor (Mark Strong) —will begin previews Wednesday evening, October 21 and open on Thursday, November 12 at the Lyceum Theatre, 149 West 45 Street. -

In David Hare's Stuff Happens (2004) Khaled S

International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences Online: 2015-10-29 ISSN: 2300-2697, Vol. 62, pp 73-90 doi:10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILSHS.62.73 CC BY 4.0. Published by SciPress Ltd, Switzerland, 2015 "Coercive Diplomacy" in David Hare's Stuff Happens (2004) Khaled S. Sirwah Department of English, Faculty of Arts, Kafreshikh University, Egypt E-mail address: [email protected]; [email protected] Keywords: coercive diplomacy, conflict, invasion, Iraq’s WMD’s, Saddam Hussein, the UN, the US, Tony Blair, war, 9/11. ABSTRACT This paper addresses George Bush the junior's decision to invade Iraq in 2003 on the plea of its weapons of mass destructions (WMD's), as delineated in David Hare's Stuff Happens (2004), a docudrama depicting the events following the 9/11 attacks and preceding the US’s invasion of Iraq. The paper explains how Bush deals with the opponents—Colin Powell, the British PM Tony Blair, and Hans Blix—opposing his decision, based on "fabricated" evidence, by employing his father's strategy of coercive diplomacy against them, depending on both his faith and his position as President. Drawing on a postcolonial approach, the analysis of Hare's piece has demonstrated two significant aspects: 1) Bush, implementing such a strategy of coercive diplomacy, has succeeded in achieving his private agenda in invading Iraq; 2) Hare is possessed of the dramatic dexterity of mixing fiction (the significant roles of the nameless fictional characters as well as the unnamed narrator-actors) with facts (the main figures of politics) for supporting play’s different conflicts. -

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Vol1.Pdf

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Volume One (of Two) Matthew John Midgley PhD University of York Theatre, Film and Television September 2015 Writing Figures of Resistance for the British Stage Abstract This thesis explores the process of writing figures of political resistance for the British stage prior to and during the neoliberal era (1980 to the present). The work of established political playwrights is examined in relation to the socio-political context in which it was produced, providing insights into the challenges playwrights have faced in creating characters who effectively resist the status quo. These challenges are contextualised by Britain’s imperial history and the UK’s ongoing participation in newer forms of imperialism, the pressures of neoliberalism on the arts, and widespread political disengagement. These insights inform reflexive analysis of my own playwriting. Chapter One provides an account of the changing strategies and dramaturgy of oppositional playwriting from 1956 to the present, considering the strengths of different approaches to creating figures of political resistance and my response to them. Three models of resistance are considered in Chapter Two: that of the individual, the collective, and documentary resistance. Each model provides a framework through which to analyse figures of resistance in plays and evaluate the strategies of established playwrights in negotiating creative challenges. These models are developed through subsequent chapters focussed upon the subjects tackled in my plays. Chapter Three looks at climate change and plays responding to it in reflecting upon my creative process in The Ends. Chapter Four explores resistance to the Iraq War, my own military experience and the challenge of writing autobiographically. -

The Judas Kiss Directed by Michael Michetti

Contact: Niki Blumberg, Tim Choy 323-954-7510 [email protected], [email protected] Boston Court Pasadena presents David Hare’s The Judas Kiss Directed by Michael Michetti February 15 – March 24 Press Opening: February 23 2019 Theatre Season Sponsored by the S. Mark Taper Foundation PASADENA, CA (January 17, 2019) — Boston Court Pasadena commences the 2019 theatre season with a rare production of David Hare’s The Judas Kiss (February 15 – March 24), which tells the story of Oscar Wilde’s love for Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas – and tracking his downfall as he endures a brutal trial and life in exile. Helmed by Artistic Director Michael Michetti, the play examines a literary icon who continues to hold onto his passionate ideals of love and beauty as his life crumbles around him. Sir David Hare, the British playwright behind Plenty, Skylight, and Stuff Happens creates “an emotionally rich drama illuminated by Hare’s customary insight and humanity.” (The Globe and MaiI). The Judas Kiss features Rob Nagle (Oscar Wilde), Colin Bates (Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas), Darius De La Cruz (Robert Ross), Will Dixon (Sandy Moffatt), Matthew Campbell Dowling (Arthur Wellesley), Mara Klein (Phoebe Cane) and Kurt Kanazawa (Galileo Masconi). In spring of 1895, Oscar Wilde was larger than life. His masterpiece, The Importance of Being Earnest, was a hit in the West End and he was the toast of London. Yet by summer he was serving two years in prison for gross indecency. Punished for “the love that dare not speak its name,” Wilde remained devoted to his beloved, Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas. -

Exploring Female Athletes' Body Perceptions

SQUEEZING IN: EXPLORING FEMALE ATHLETES’ BODY PERCEPTIONS Mallory E. Mann A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2015 Committee: Vikki Krane, Advisor Dafina-Lazarus Stewart Graduate Faculty Representative Nancy Spencer Dryw Dworsky ii ABSTRACT Vikki Krane, Advisor Much attention has been paid to female college athlete body image over the last three decades. However, relatively few inquiries employed a holistic approach that examined the myriad of interrelated sociocultural and personal factors influencing athletes’ body perceptions. The primary purpose of the current study was to explore female college athletes’ body image in both social and sport settings. A secondary purpose was to investigate the sociocultural context and how it influenced athletes’ body perceptions. Finally, this study sought to understand the ways in which female athletes’ social identities helped explain their body-related behaviors. Feminist and intersectional methodological approaches guided this inquiry to create partial, in- depth understandings of how female athletes think about and relate to their physiques. The study is particularly unique in its commitment to representing multiple, diverse stories from athletes without privileging one type of body perception. Using an intersectional methodology contextualized athletes body descriptions to uncover deeper meanings and underlying factors. Twenty female college athletes participated in unstructured interviews. These athletes represented eight different varsity sports at NCAA Division I, II, and III institutions. This study offers a new perspective on the relationship between motivational team climate and female athlete body image. While task-oriented team climates still appear to serve as a protective factor against body disturbances among athletes, findings also indicated that a team’s obsession with the body seemed more closely tied to body image issues than a team’s goal orientation. -

Appendix Plays Discussed in This Book

Appendix Plays Discussed in This Book Abe Lincoln in Illinois, Robert Sherwood. 1938 Broadway run: 472 performances. 1993 Lincoln Center revival: 27 previews, 40 performances. Abraham Lincoln, John Drinkwater. 1919 Broadway run: 193 per- formances. 1929 Broadway revival: 8 performances. Abraham Lincoln’s Big Gay Dance Party, Aaron Loeb. 2008 San Francisco. 2010 off-Broadway run. American Iliad, Donald Freed. 2001 Burbank, California. As the Girls Go, William Roos (book), Jimmy McHugh (music), Harold Adamson (lyrics). 1948 Broadway run: 414 performances. Assassins, John Weidman (book), Stephen Sondheim (music and lyrics). 1990 off-Broadway run: 73 performances. 1992 London revival. 2004 Broadway revival: 26 previews, 101 performances. The Best Man, Gore Vidal. 1960 Broadway run: 520 performances. 2000 Broadway revival: 15 previews, 121 performances. Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson, Alex Timbers (book), Michael Friedman (music and ly73rics). 2008 Los Angeles. 2009 and 2010 off-Broadway runs. Buchanan Dying, John Updike. 1976 Franklin and Marshall College. Bully! Jerome Alden. 1977 Broadway run: 8 previews, 8 performances. 2006 off Broadway revival. The Bully Pulpit, Michael O. Smith. 2008 off-Broadway. Camping with Henry and Tom, Mark St. Germain. 1995 off- Broadway run: 105 performances. Numerous regional theater revivals since then. An Evening with Richard Nixon, Gore Vidal. Broadway run: 14 previews, 16 performances. First Lady, Katherine Dayton and George S. Kaufman. 1935 Broadway run: 246 performances. 1952 off-Broadway revival. 1980 Berkshire Theater Festival revival. 1996 Yale Repertory Theatre revival. First Lady Suite, Michael John LaChiusa. 1993 off-Broadway run: 32 performances. Revivals include Los Angeles 2002, off Broadway 2004, and London 2009. 160 Appendix Frost/Nixon, Peter Morgan. -

Stephanie Braun Plan

FASHION & WEDDING EDITION! TRICIA FREDERICK Sassy, Sexy Sophisticated Style Stylist to the stars River Valley Stephanie Braun PLAN IT! Parties & anna uehling Weddings Plus Born to Create FREE! RiveRvalleywoman.com SeptembeR 2015 • volume 3 • Issue 4 n Early Childhood n Invisalign n Mini Implants Checkups n Whitening n Mouth Guards n Cosmetic Dentistry n Root Canals n Snoring Appliances n Orthodontics (Braces) n Extractions n Extended Hours Dr. Daniel Drugan Dr. Gregory Kjellberg Dr. Larry Parker Dr. Linda Giang-Carlson 127 N. Broadway, New Ulm, MN 56073 phone (507) 233-9400 toll-free (866) 405-4693 after hours (507) 233-9400 www.newulmdental.com 027743 70 18 10 52 contents • Publisher { 2015 } New Century Press { september Chief Operating Officer 6 Jim Hensley General Manager Lisa Miller GO Please direct all editorial inquiries Parties and Weddings Plus ..................................................... 18 and suggestions to: St. Peter: Where History & Progress Meet ....................................... 32 Managing Editor Eileen Madsen Redwood Area: Take It In....................................................... 34 [email protected] Fun, Festivals and Frolics ....................................................... 38 River Valley Road Trip .......................................................... 44 Sales Manager Natasha Weis Springfield, A Lot to Share ..................................................... 51 507-227-2545 Treasures...................................................................... 66 [email protected] Sales -

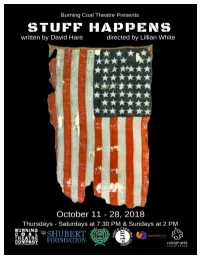

Study-Guide-For-STUFF-HAPPENS

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION AND THE RATIONALE FOR THE INVASION OF IRAQ One of the most weighty justifications for the United States' 2003 invasion of the Iraqi Republic was the pursuit of Weapons of Mass Destruction (hereafter referred to WMD) by the regime of President Saddam Hussein in violation of United Nations Security Council Resolutions 686 & 687. The potential for the Iraqi regime to develop nuclear capability, or that it already held chemical and biological weapons, sat at the forefront of President President George W. Bush Gives a Speech in Cincinatti George W. Bush's rhetoric. In his October 7, 2002 speech at the Cincinatti Museum Center, Bush noted: Tonight I want to take a few minutes to discuss a grave threat to peace, and America's determination to lead the world in confronting that threat. The threat comes from Iraq. It arises directly from the Iraqi regime's own actions -- its history of aggression, and its drive toward an arsenal of terror. Eleven years ago, as a condition for ending the Persian Gulf War, the Iraqi regime was required to destroy its weapons of mass destruction, to cease all development of such weapons, and to stop all support for terrorist groups. The Iraqi regime has violated all of those obligations. It possesses and produces chemical and biological weapons. It is seeking nuclear weapons. It has given shelter and support to terrorism, and practices terror against its own people.1 Or in his March 19, 2003 address to the nation from the Oval Office he began: My fellow citizens, at this hour, American and coalition forces are in the early stages of military operations to disarm Iraq, to free its people and to defend the world from grave danger. -

Forty-Five Minutes That Changed the World: the September Dossier, British Drama, and the New Journalism George Potter Valparaiso University, [email protected]

Valparaiso University ValpoScholar English Faculty Publications Department of English 2017 Forty-Five Minutes that Changed the World: The September Dossier, British Drama, and the New Journalism George Potter Valparaiso University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/eng_fac_pub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Potter, G. “Forty-Five Minutes that Changed the World: The eS ptember Dossier, British Drama, and the New Journalism.” College Literature 44.2 (2017): 231-55. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Forty-five Minutes that Changed the World: The September Dossier, British Drama, and the New Journalism George Potter College Literature, Volume 44, Number 2, Spring 2017, pp. 231-255 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/lit.2017.0011 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/656975 Access provided by Valparaiso University (9 Jun 2017 20:59 GMT) FORTY-FIVE MINUTES THAT CHANGED THE WORLD: THE SEPTEMBER DOSSIER, BRITISH DRAMA, AND THE NEW JOURNALISM GEORGE POTTER September 24, 2002. Just over a year after the attacks of 9/11 and just under two weeks after US President George W. Bush implored the United Nations to take a stand against Iraq, the British Labor government released a dossier analyzing Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction capabilities. -

Winner of 3Rd Annual YALE DRAMA SERIES Award for Playwriting Announced by David Hare

Press contact: Sam Rudy 212 221 8466 or 917 864 1503 Winner of 3rd annual YALE DRAMA SERIES Award for Playwriting announced by David Hare Frances Ya-Chu Cowhig to receive $10,000 award from David C. Horn Foundation for her play LIDLESS about Guantanamo Bay Play to receive staged reading at Yale Rep in September '09 and will be published by Yale University Press (Monday, March 16, 2009) The award-winning playwright David Hare has announced that Frances Ya-Chu Cowhig is the recipient of the 2009 Yale Drama Series Award for Playwriting for her play LIDLESS. Ms. Cowhig's Yale Drama Series prize includes a $10,000 award from the David C. Horn Foundation, along with a staged reading of the work at Yale Rep in September 2009 (date TBA) and the publication of the play by Yale University Press. Mr. Hare, the Olivier Award-winning playwright and Oscar-nominated screenwriter, served as judge of this year's third annual Yale Drama Series, having succeeded playwright Edward Albee, who selected the Series' winning plays during the award's inaugural year in 2007 and again last year. Mr. Hare will repeat as judge of the Yale Drama Series in 2010. Along with the first place honor for LIDLESS, Mr. Hare announced that THE DANGER OF BLEEDING BROWN by Enrique Urueta and HELL MONEY by Ruth McKee had been selected as runners-up for the 2009 competition. LIDLESS -- chosen from 650 submissions -- is Ms. Cowhig's play about a former Guantanamo Bay detainee who journeys to the home of his female U.S.