Before the Public Utilities Commission of the State Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T680 76-Inch Sleeper KENWORTH the WORLD’S BEST

T680 76-Inch Sleeper KENWORTH THE WORLD’S BEST. BOLD INTELLIGENT PRODUCTIVE THE CONTINUED BENCHMARK IN PERFORMANCE AND PROFITABILITY Kenworth’s T680 is a true game changer in the business of running trucks at a profit. Aggressive aerodynamic design. A fully integrated, highly efficient PACCAR Powertrain. REWARDING Uptime engineering that results in an unmatched work ethic. Plus a level of luxury, craftsmanship and intuitive control that makes the T680 The Driver’s Truck™ — a factor that helps every Kenworth fleet attract and retain the industry’s best operators. T680 76-Inch Sleeper THE CUTTING EDGE JUST GOT A WHOLE LOT SHARPER. Start with the most highly evolved aerodynamic long-haul tractor, the Kenworth T680. Add special factory-installed aerodynamic enhancements for the tractor that combine to reduce drag to an absolute minimum. Optimize the powertrain with the fuel efficient PACCAR MX-13 engine, PACCAR transmission and PACCAR drive axles. Incorporate Kenworth’s Idle Management System, which eliminates the need to run the truck for off-duty temperature control. And integrate real-time reporting technology to help the driver run in the sweet spot for maximum fuel efficiency. Kenworth luxury, craftsmanship, reliability and driver satisfaction also come as part of the deal. KENWORTH THE WORLD’S BEST. Fuel Saving Intelligence: • Most advanced and aerodynamic truck ever produced by Kenworth • Predictive Cruise Control • Driver Performance Assistant • Front air dams, 19 inch side extenders and chassis fairing extenders, • Predictive Neutral -

Ac Compressors

A/C COMPRESSORS 2019 PARTS GUIDE allianceparts.com INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION ALL-MAKES HEAVY-DUTY A/C COMPRESSORS With parts and accessories for all makes and models1, Alliance Parts is the smartest choice for value on the road. Readily available, easily affordable and assured in quality, Alliance has everything you need to deliver. PARTS NUMBERING SYSTEM All part numbers in this program contain the prefix ABP and N83 (the company-assigned code for this program). The remaining digits are based on part and design. Example – ABP N83 304QP7H154417 All Alliance Parts products in the catalog are set up with an Alliance part number. In the back of this catalog, you will find an extensive cross-reference list. This will help link another manufacturer’s part to an Alliance ABP number. WARRANTY Alliance products are backed by a 1-year/unlimited-mile standard warranty. Additional warranty coverage may apply where specified. Illustrations and photographs used in this catalog may vary slightly from the actual product. Prototype samples are sometimes used for photography. The production parts may vary slightly. Availability of products shown in this catalog is subject to change without notice. 1For nearly all heavy-duty truck makes and models. 2019 | ALLIANCE PARTS A/C COMPRESSORS 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE WOBBLE PLATE COMPRESSORS 1 SPECIFICATIONS ...............................................................................................................................................5 PARTS LIST .........................................................................................................................................................6 -

Trp Parts Catalog

Parts for Trucks, Trailers & Buses ® BUS PARTS 5 CAB Proven, reliable and always innovative. TRP® offers reliable aftermarket products that are designed and tested to exceed customers’ expectations regardless of the vehicle make, model or age. GLASS • BUMPERS • MIRRORS • MIRROR HARDWARE • WIPER BLADES TABLE OF CONTENTS Tested. Reliable. Guaranteed. CAB BUS GLASS Cab Amtran ...........................5-7 Blue Bird .........................5-8 Choosing the right replacement part or service for Carpenter .......................5-10 your vehicle—whether you own Navistar .........................5-10 one, or a fleet—is one of the most important decisions you Thomas .........................5-11 can make for your business. And, with tested TRP® parts Ward ...........................5-14 it’s an easy decision. Wayne ..........................5-14 Regardless of the make you drive, TRP® quality CABOVER GLASS replacement parts are Ford ............................5-15 engineered to fit your truck, trailer or bus. Choose the Freightliner ......................5-15 parts that give you the best Hino ............................5-16 value for your business. Check them out at an approved Isuzu ...........................5-17 TRP® retailer near you. Mack ...........................5-18 Mitsubishi .......................5-19 Navistar .........................5-20 Nissan ..........................5-21 The cross reference information in this catalog is based upon data provided Peterbilt .........................5-21 by several industry sources and our partners. While every attempt is made to ensure the information presented Volvo ...........................5-22 is accurate, we bear no liability due to incorrect or incomplete information. Product Availability Due to export restrictions and market ® demands, not all products are TRP North America always available in every location. 750 Houser Way N. Check for availability in your area with your local TRP® Distributor. -

Electric Vehicle Market Status - Update Manufacturer Commitments to Future Electric Mobility in the U.S

Electric Vehicle Market Status - Update Manufacturer Commitments to Future Electric Mobility in the U.S. and Worldwide September 2020 Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Drivers of Global Electric Vehicle Growth – Global Goals to Phase out Internal Combustion Engines ..... 6 Policy Drivers of U.S. Electric Vehicle Growth ........................................................................................... 8 Manufacturer Commitments ....................................................................................................................... 10 Job Creation ................................................................................................................................................ 13 Charging Network Investments .................................................................................................................. 15 Commercial Fleet Electrification Commitments ........................................................................................ 17 Sales Forecast.............................................................................................................................................. 19 Battery Pack Cost Projections and EV Price Parity ................................................................................... -

Mckissick Trucking Inc. Expedited Settlement Agreement

Docket No. CAA-03-2021-0069 FILED April 20, 2021 7:48 AM U.S. EPA Region III, Regional Hearing Clerk BEFORE THE UNITED STA TES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGE CY REGION Ill 1650 Arch Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103-2029 ) IN THE MATTER OF: DOCKET NO.: CAA-03-2021-0069 ) ) McKissick Trucking, Inc. ) EXPEDITED SETTLEMENT 699 Pinegrove School Road ) AGREEMENT Venus, PA 16364 ) ) Respondent. EXPEDITED SETTLEME T AGREEME T 1. This Expedited Settlement Agreement (or "Agreement") is entered into by the Director, Enforcement & Compliance Assurance Division, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region Ill ("Complainant"), and Mc Kissick Trucking, Inc. ("Respondent"), pursuant to Section 205(c)(l) of the Clean Air Act ("CAA"), as amended, 42 U.S.C § 7524(c)(l), and the Consolidated Rules ofPractice Governing the Administrative Assessment ofCivil Penalties and the Revocation/Termination or Suspension ofPermits ("Consolidated Rules of Practice"), 40 C.F.R. Part 22 (with specific reference to 40 C.F.R. §§ 22. I 3(b), 22.18(b)(2) , and (3)). The Administrator has delegated this authority to the Regional Administrator who, in turn, has delegated it to the Complainant. 2. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ("EPA") has jurisdiction over the above-captioned matter pursuant to Section 205(c)(l) of the CAA, 42 U.S.C § 7524(c)(l), and 40 C.F.R. §§ 22.l(a)(2) and 22.4 of the Consolidated Rules of Practice. 3. At all times relevant to this Agreement, Respondent, a Pennsylvania limited liability company, was, and currently is, a "person" as defined under Section 302(e) of the CAA, 42 U.S.C § 7602(e), and the owner and operator of the facility located at 609 Pinegrove School Road, Venus, PA 16364 (the "Facility"). -

On-Road Truck Market

Donaldson Delivers Filters and Service That Go the Distance Road Ready Performance Durable, rugged and built for the long haul, Donaldson replacement filters are manufactured to the same quality standards as the original. Donaldson delivers the most comprehensive line of filtration solutions for your trucks – and fleets. Downtime means lost revenue. To keep your trucks on the road, you need filters that deliver superior performance – and a reliable supplier that offers complete coverage for your entire truck. Filters are an important part of any effective truck maintenance program. They need to withstand the harsh demands of the road – the starts, the stops, the idling and the strain of a heavy load. Donaldson filters deliver Cabin Air Filtration the right combination of quality and value that help get your trucks to their next scheduled service without interruption. Donaldson Delivers. Air Filtration Crankcase Innovative filtration solutions for engines, Filtration equipment and the people who use them. Power Steering Filtration • Industry-Leading technology – uncompromising product quality • OE Grade – Donaldson is the first-fit choice of equipment manufacturers around the world • Broad Product Coverage – air, lube, fuel, coolant and hydraulic filters and systems, plus exhaust, emissions, and more • Consistent Product Availability – the filters you need, when you need them • Comprehensive Customer Service – experienced and knowledgeable sales and technical support teams • Specialized Fleet Services – designed specifically for the transportation -

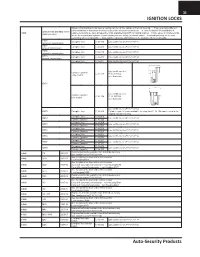

IGNITION LOCKS Auto-Security Products

31 IGNITION LOCKS Nissan / Infi niti ignition locks have a casting number on the outside of the lock housing. There are many different minor variations in this range of locks, mostly in the electrical connections. In order to simplify the availability of Ignition locks identifi ed by the Infi niti replacement parts we have grouped the locks available from ASP by casting number. Future sales of complete locks casting number will be the housing and cylinder of each casting number without electrical switch. Electrical switches will be sold separately whenever possible. Also cylinder repair kits will continue to be available whenever possible. AS51 Complete lock C-16-410 Use tumbler series P-16-181/184 automatic transmission AS51 Complete lock C-16-409 Use tumbler series P-16-181/184 manual transmission AS55 Complete lock C-16-412 Use tumbler series P-16-181/184 automatic transmission AS55 Complete lock C-16-411 Use tumbler series P-16-181/184 manual transmission Complete lock C-16-401 Use tumbler series P-16-161/164 Use tumbler series Cylinder repair kit C-16-127 P-16-161/164 early models see illustration KV71 Use tumbler series Cylinder repair kit C-16-134 P-16-161/164 late models see illustration Use tumbler series P-16-161/164 KV75 Complete lock C-16-402 Cylinder repair kit is not available, the plug from C-16-134 can be used in the original cylinder housing. Complete lock C-16-403 SK53 Use tumbler series P-16-161/164 Cylinder repair kit C-16-126 Complete lock C-16-404 SK61 Use tumbler series P-16-161/164 Cylinder repair kit C-16-129 Complete lock C-16-405 SK63 Use tumbler series P-16-161/164 Cylinder repair kit C-16-129 Complete lock C-16-406 SK66 Use tumbler series P-16-161/164 Cylinder repair kit C-16-133 Complete lock C-16-407 SK67 Use tumbler series P-16-161/164 Cylinder repair kit C-16-133 Complete lock C-16-408 SK69 Use tumbler series P-16-161/164 Cylinder repair kit C-16-133 Replacement locks available from Infi niti dealers only. -

Page 1 of 32 VEHICLE RECALLS by MANUFACTURER, 2000 Report Prepared 1/16/2008

Page 1 of 32 VEHICLE RECALLS BY MANUFACTURER, 2000 Report Prepared 1/16/2008 MANUFACTURER RECALLS VEHICLES ACCUBUIL T, INC 1 8 AM GENERAL CORPORATION 1 980 AMERICAN EAGLE MOTORCYCLE CO 1 14 AMERICAN HONDA MOTOR CO 8 212,212 AMERICAN SUNDIRO MOTORCYCLE 1 2,183 AMERICAN SUZUKI MOTOR CORP. 4 25,023 AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION CORP. 5 1,441 APRILIA USA INC. 2 409 ASTON MARTIN 2 666 ATHEY PRODUCTS CORP. 3 304 B. FOSTER & COMPANY, INC. 1 422 BAYERISCHE MOTOREN WERKE 11 28,738 BLUE BIRD BODY COMPANY 12 62,692 BUELL MOTORCYCLE CO 4 12,230 CABOT COACH BUILDERS, INC. 1 818 CARPENTER INDUSTRIES, INC. 2 6,838 CLASSIC LIMOUSINE 1 492 CLASSIC MANUFACTURING, INC. 1 8 COACHMEN INDUSTRIES, INC. 8 5,271 COACHMEN RV COMPANY 1 576 COLLINS BUS CORPORATION 1 286 COUNTRY COACH INC 6 519 CRANE CARRIER COMPANY 1 138 DABRYAN COACH BUILDERS 1 723 DAIMLERCHRYSLER CORPORATION 30 6,700,752 DAMON CORPORATION 3 824 DAVINCI COACHWORKS, INC 1 144 D'ELEGANT CONVERSIONS, INC. 1 34 DORSEY TRAILERS, INC. 1 210 DUTCHMEN MANUFACTURING, INC 1 105 ELDORADO NATIONAL 1 173 ELECTRIC TRANSIT, INC. 1 54 ELGIN SWEEPER COMPANY 1 40 E-ONE, INC. 1 3 EUROPA INTERNATIONAL, INC. 2 242 EXECUTIVE COACH BUILDERS 1 702 FEATHERLITE LUXURY COACHES 1 83 FEATHERLITE, INC. 2 3,235 FEDERAL COACH, LLC 1 230 FERRARI NORTH AMERICA 8 1,601 FLEETWOOD ENT., INC. 5 12, 119 FORD MOTOR COMPANY 60 7,485,466 FOREST RIVER, INC. 1 115 FORETRAVEL, INC. 3 478 FOURWINNS 2 2,276 FREIGHTLINER CORPORATION 27 233,032 FREIGHTLINER LLC 1 803 GENERAL MOTORS CORP. -

W990 76-Inch Mid-Roof Sleeper KENWORTH the WORLD’S BEST

W990 76-Inch Mid-Roof Sleeper KENWORTH THE WORLD’S BEST. PRESENCE, POWER AND PERSONAL STYLE WRAPPED IN A WORLD-CLASS DESIGN THAT REDEFINES THE LONG-HOOD CONVENTIONAL. Kenworth’s long-hood conventional is the enduring symbol of American trucking — a perfect fusion of power, luxury, craftsmanship and traditional styling. For most professional drivers, it also represents the ultimate reward, a uniquely personal icon that stands for their dedication, achievement and sense of pride. Through the decades, our job has been to carefully — and continually — refine this classic without changing what made it great. Introducing the Kenworth W990, the truck for those who put a premium on making a personal statement. It comes with uncompromising styling, straight ahead performance, premium finishes and lifestyle amenities that put you way ahead of the pack. It just doesn’t get any better than this. W990 76 Inch Mid-Roof Sleeper KENWORTH THE WORLD’S BEST. BOLD. PROUD. TIMELESS. CONFIDENT. AND PERSONAL. LIFE ON THE ROAD HAS NEVER LOOKED SO GOOD. When you drive a Kenworth W990, others notice. It is a look. It is a sound. It is the undeniable recognition of your achievement. With 131.5 inches from bumper to back-of-cab, no one ignores the sheer presence of Kenworth’s latest long-hood classic. Nor will they miss your personalized message so clearly reflected in customized brightwork, hand-stitched upholstery and soul-stirring dual chromed stacks. Then there’s the hand-masked, hand-finished paint job, with a luster so deep you can see it for miles. And the exclusive styling of the Kenworth W990... -

Advanced Technology Equipment Manufacturers*

Advanced Technology Equipment Manufacturers* Revised 04/21/2020 On-Road (Medium/Heavy Duty, Terminal Tractors) OEM Model Technology Vocations GVWR Type Altec Industries, Inc Altec 12E8 JEMS ePTO ePTO ePTO, Utility > 33,000, 26,001 - 33,000 New Altec Industries, Inc Altec JEMS 1820 and 18E20 ePTO ePTO ePTO, Utility > 33,000, 26,001 - 33,000 New Altec Industries, Inc Altec JEMS 4E4 with 3.6 kWh Battery ePTO ePTO, Utility 16,001-19,500, 19,501-26,000 New Altec Industries, Inc Altec JEMS 6E6 with 3.6 kWh Battery ePTO ePTO, Utility 16,001-19,500, 19,501-26,000 New Autocar Autocar 4x2 and 6x4 Xpeditor with Cummins-Westport ISX12N Engine Near-Zero Engine Truck > 33,001 New Autocar Autocar 4x2 and 6x4 Xpeditor with Cummins-Westport L9N Engine Near-Zero Engine Refuse > 33,001 New Blue Bird Blue Bird Electric Powered All American School Bus Zero Emission Bus, School Bus > 30,000 New Blue Bird Blue Bird Electric Powered Vision School Bus 4x2 Configuration Zero Emission Bus, School Bus > 30,000 New BYD Motors BYD 8Y Electric Yard Tractor Zero Emission Terminal Truck 81,000 New BYD Motors BYD C10 45' All-Electric Coach Bus Zero Emission Bus 49,604 New BYD Motors BYD C10MS 45' All-Electric Double-Decker Coach Bus Zero Emission Transit Bus 45' New BYD Motors BYD C6 23' All-Electric Coach Bus Zero Emission Bus 18,331 New BYD Motors BYD K11 60' Articulated All-Electric Transit Bus Zero Emission Bus 65,036 New BYD Motors BYD K7M 30' All-Electric Transit Bus Zero Emission Bus, Transit Bus 30' New BYD Motors BYD K9 40' All-Electric Transit Bus Zero Emission -

Part 573 Safety Recall Report 20E-038

OMB Control No.: 2127-0004 Part 573 Safety Recall Report 20E-038 Manufacturer Name : Dana Incorporated Submission Date : JUL 21, 2020 NHTSA Recall No. : 20E-038 Manufacturer Recall No. : NR Manufacturer Information : Population : Manufacturer Name : Dana Incorporated Number of potentially involved : 1,001 Address : 3939 Technology Drive Estimated percentage with defect : 60 % Maumee OH 43537 Company phone : 419-887-3000 Equipment Information : Brand / Trade 1 : Dana Heavy Vehicle System Model : Output Shaft – 131536 Part No. : 131536 Size : NR Function : OS in DriveAxle Descriptive Information : The issue potentially affects the output shaft component of certain drive axles manufactured for commercial vehicles and distributed by Dana. Dana has identified the manufacturing dates of potentially affected units and customers. Dana has already communicated with all potentially affected customers. Production Dates : NOV 19, 2019 - DEC 05, 2019 Description of Defect : Description of the Defect : Certain output shafts built in front rear drive axles may not have been properly heat treated, which can cause the shaft to fracture at the transition of the shaft splines to the thread. FMVSS 1 : NR FMVSS 2 : NR Description of the Safety Risk : If the rear axle output shaft fractures, the shaft or interaxle driveline could detach from the vehicle and cause an accident or injury. Description of the Cause : Improper machine settings during the induction hardening process resulted in the over heat treatment of certain output shafts. Identification of Any -

Hvy Dty Veh & Eng Res. Guide

The U.S. Department Of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency And Renewable Energy’s National Alternative Fuels Hotline Heavy-Duty Vehicle and Engine Resource Guide This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION CONTACT THE HOTLINE 800-423-1DOE • 703-528-3500 FAX: 703-528-1953 EMAIL: [email protected] Introduction Engine manufacturers are moving forward when it comes to alternative fuel engine technology. This model year (MY96), heavy-duty engine manufacturers are offering a number of natural gas models with additional models nearing production. Electric vehicle manufacturers have several products available with new models nearing completion. Although Caterpillar is the only manufacturer offering propane as a fuel option, Detroit Diesel Corp. (DDC) will be demonstrating a prototype model in 1996, and Cummins will release a model within MY96. Many manufacturers are offering natural gas engines in response to California Air Resource Board’s strict bus emission standards which are effective MY96.