Pharmaco-Epidemiologic Methods for a Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effects of Antipsychotic Treatment on Metabolic Function: a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis

The effects of antipsychotic treatment on metabolic function: a systematic review and network meta-analysis Toby Pillinger, Robert McCutcheon, Luke Vano, Katherine Beck, Guy Hindley, Atheeshaan Arumuham, Yuya Mizuno, Sridhar Natesan, Orestis Efthimiou, Andrea Cipriani, Oliver Howes ****PROTOCOL**** Review questions 1. What is the magnitude of metabolic dysregulation (defined as alterations in fasting glucose, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and triglyceride levels) and alterations in body weight and body mass index associated with short-term (‘acute’) antipsychotic treatment in individuals with schizophrenia? 2. Does baseline physiology (e.g. body weight) and demographics (e.g. age) of patients predict magnitude of antipsychotic-associated metabolic dysregulation? 3. Are alterations in metabolic parameters over time associated with alterations in degree of psychopathology? 1 Searches We plan to search EMBASE, PsycINFO, and MEDLINE from inception using the following terms: 1 (Acepromazine or Acetophenazine or Amisulpride or Aripiprazole or Asenapine or Benperidol or Blonanserin or Bromperidol or Butaperazine or Carpipramine or Chlorproethazine or Chlorpromazine or Chlorprothixene or Clocapramine or Clopenthixol or Clopentixol or Clothiapine or Clotiapine or Clozapine or Cyamemazine or Cyamepromazine or Dixyrazine or Droperidol or Fluanisone or Flupehenazine or Flupenthixol or Flupentixol or Fluphenazine or Fluspirilen or Fluspirilene or Haloperidol or Iloperidone -

Treatment of Schizophrenia Course Director: Philip Janicak, M.D

S6735- Treatment of Schizophrenia Course Director: Philip Janicak, M.D. #APAAM2016 Saturday, May 14, 2016 Marriott Marquis - Marquis Ballroom D psychiatry.org/ annualmeetingS4637 ANNUAL MEETING May 14-18, 2016 • Atlanta Reference • Janicak PG, Marder SR, Tandon R, Goldman M (Eds.). Schizophrenia: Recent Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. Schizophrenia: Recent Diagnostic Advances, Neurobiology, and the Neuropharmacology of Antipsychotic Drug Therapy Rajiv Tandon, MD Professor of Psychiatry University of Florida College of Medicine Gainesville, Florida Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association New York, New York May 3–7, 2014 Disclosure Information MEMBER, WPA PHARMACOPSYCHIATRY SECTION MEMBER, DSM-5 WORKGROUP ON PSYCHOTIC DISORDERS A CLINICIAN AND CLINICAL RESEARCHER Pharmacological Treatment of Any Disease • Know the Disease that you are treating • Nature; Treatment targets; Treatment goals; • Know the Treatments at your disposal • What they do; How they compare; Costs; • Principles of Treatment • Measurement-based; Targeted; Individualized Program Outline • Nature and Definition of psychosis? • Clinical description • What is wrong in psychotic illness • Dimensions of Psychopathology • Neurobiological Abnormalities • Mechanisms underlying antipsychotic effects? • What contributes to Efficacy • Basis of Side-effect differences 5 Challenges in DSM-IV Construct of Psychotic Disorders ♦ Indistinct Boundaries ♦ With Other Disorders (eg., with OCD) ♦ Within Group of Psychotic Disorders (eg. between -

Psychiatric Medications in Behavioral Healthcarev5

Copyright © The University of South Florida, 2012 Psychiatric Medications in Behavioral Healthcare An Important Notice None of the pages in this tutorial are meant to be a replacement for professional help. The science of medicine is constantly changing, and these changes alter treatment and drug therapies as a result of what is learned through research and clinical experience. The author has relied on resources believed to be reliable at the time material was developed. However, there is always the possibility of human error or changes in medical science and neither the authors nor the University of South Florida can guarantee that all the information in this program is in every respect accurate or complete and they are not responsible for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from the use of such information. Each person that reads this program is encouraged to confirm the information with other sources and understand that it not be interpreted as medical or professional advice. All medical information needs to be carefully reviewed with a health care provider. Course Objectives At the completion of this program participants should be able to: • Identify at 5 categories of medications used to treat the symptoms of psychiatric disorders, the therapeutic effects of medications in each category, and the side effects associated with medications in each category. • Identify at least 5 medications and the benefits of those medications as compared to the medications. • Identify at least 5 reasons that a person may stop taking medications or not take medications as prescribed. • Demonstrate your learned understanding of psychiatric medications by passing the combined post‐ tests. -

A New Therapeutic Target for Spasticity and Neuropathic Pain

UNIVERSITÉ D’AIX-MARSEILLE ÉCOLE DOCTORALE SCIENCES DE LA VIE ET DE LA SANTÉ FACULTÉ DE MÉDECINE UNIVERSITAT AUTÒNOMA DE BARCELONA INSTITUT DE NEUROCIÈNCIES UAB DEPARTAMENT DE BIOLOGIA CEL·LULAR, FISIOLOGIA I IMMUNOLOGIA Thesis Presented to obtain the degree of Doctor PhD program: Neuroscience Irene SANCHEZ-BRUALLA The potassium-chloride cotransporter KCC2: a new therapeutic target for spasticity and neuropathic pain Defended on November 26th 2018 before the jury: Dr. Frédérique SCAMPS (Chargé de recherche, Inserm, Montpellier) Reporter Dr. Julian TAYLOR (Directeur de recherche, Stoke Mandeville Spinal Research, Reporter Aylesbury) Dr. Sandrine BERTRAND (Directeur de recherche, CNRS, Bordeaux) Examiner Dr. Patrick DELMAS (Directeur de recherche, CNRS, Marseille) Examiner Dr. Hatice KUMRU (Praticien hospitalier, Institut Guttmann, Barcelona) Examiner Dr. Vicente MARTÍNEZ (Professeur titulaire, UAB, Barcelona) Examiner Dr. Frédéric BROCARD (Directeur de recherche, CNRS, Marseille) Thesis director Dr. Esther UDINA (Professeur titulaire, UAB, Barcelona) Thesis director This thesis was tutored by Dr. Xavier NAVARRO (Professeur titulaire, UAB, Barcelona) The potassium-chloride cotransporter KCC2 : a new therapeutic target for spasticity and neuropathic pain PhD Program in Integrative and Clinical Neuroscience Institut de Neurosciences de la Timone Aix-Marseille Université Programa de Doctorat en Neurociències Institut de Neurociències UAB Departament de Biologia Cel·lular, Fisiologia i Immunologia Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Author Irene Sánchez Brualla Thesis director Thesis director Tutor Frédéric Brocard Esther Udina Bonet Xavier Navarro Acebes À mes directeurs, mes collègues et mes amis. A mis directores, mis compañeros de trabajo, mi familia y mis amigos. Acknowledgements Je veux remercier spécialement Laurent Vinay, sans lequel je n’aurai pas eu l’opportunité de faire cette thèse. -

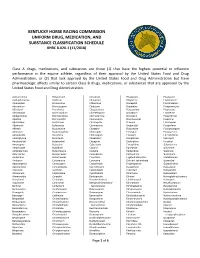

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

A Unitary Mechanism of Calcium Antagonist Drug Action '(Dihydropyridine/Nifedipine/Verapamil/Neuroleptic/Diltiazem) KENNETH M

Proc. Nati Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 80, pp. 860-864, February 1983 Medical Sciences A unitary mechanism of calcium antagonist drug action '(dihydropyridine/nifedipine/verapamil/neuroleptic/diltiazem) KENNETH M. M. MURPHY, ROBERT J. GOULD, BRIAN L. LARGENT, AND SOLOMON H. SNYDER* Departments of Neuroscience, Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, and Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 72S North Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21205 Contributed by Solomon H. Snyder, October 21, 1982 ABSTRACT [3H]Nitrendipine binding to drug receptor sites liquid scintillation counting were carried out as described (7). associated with calcium channels is allosterically regulated by a All experiments, performed in triplicate, were replicated at diverse group of calcium channel antagonists. Verapamil, D-600 least three times with similar results. (methoxyverapamit), tiapamil, lidoflazine, flunarizine, cinnari- Guinea pig ileum longitudinal muscles were prepared for zine, and prenylamine all reduce P3H]nitrendipine binding affin- recording as described by Rosenberger et aL (13) and incubated ity. By contrast, diltiazem, a benzothiazepine calcium channel an- in a modified Tyrode's buffer (14) at 370C with continuous aer- tagonist, enhances [3H]nitrendipine binding. All these drugeffects ation with 95% '02/5% CO2. Ileum longitudinal muscles were involve a single site allosterically linked to the [3H]nitrendipine incubated in this buffer for 30 min before Ca2"-dependent con- binding site. Inhibition of t3H]nitrendipine binding by prenyl- were as described Jim et aL amine, lidoflazine, or tiapamil is reversed by D-600and diltiazem, tractions recorded by (15). which alone respectively slightlyreduceorenhance H]mnitrendipine RESULTS binding. Diltiazem reverses the inhibition of [3H]nitrendipine binding by D-600. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/00398.69 A1 Wermeling Et Al

US 200600398.69A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/00398.69 A1 Wermeling et al. (43) Pub. Date: Feb. 23, 2006 (54) INTRANASAL DELIVERY OF Publication Classification ANTIPSYCHOTC DRUGS (51) Int. Cl. A6IK 9/14 (2006.01) A61 K 3/445 (2006.01) A6IL 9/04 (2006.01) (76) Inventors: Daniel Wermeling, Lexington, KY (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................. 424/46; 514/317 (US); Jodi Miller, Acworth, GA (US) (57) ABSTRACT An intranasal drug product is provided including an antip Correspondence Address: Sychotic drug, Such as haloperidol, in Sprayable Solution in MAYER, BROWN, ROWE & MAW LLP an intranasal metered dose Sprayer. Also provided is a P.O. BOX2828 method of administering an antipsychotic drug, Such as CHICAGO, IL 60690-2828 (US) haloperidol, to a patient, including the Step of delivering an effective amount of the antipsychotic drug to a patient intranasally using an intranasal metered dose Sprayer. A (21) Appl. No.: 10/920,153 method of treating a psychotic episode also is provided, the method including the Step of delivering an antipsychotic drug, Such as haloperidol, intranasally in an amount effective (22) Filed: Aug. 17, 2004 to control the psychotic episode. Patent Application Publication Feb. 23, 2006 US 2006/00398.69 A1 30 525 2 20 -- Treatment A (M) S 15 - Treatment B (IM) 10 -- Treatment C (IN) i 2 O 1 2 3 4 5 6 Time Post-dose (hours) F.G. 1 US 2006/0039869 A1 Feb. 23, 2006 INTRANASAL DELIVERY OF ANTIPSYCHOTC therefore the dosage form of choice in acute situations. In DRUGS addition, the oral Solution cannot be "cheeked' by patients. -

Police Science Technical Abstracts and Notes

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 60 | Issue 2 Article 19 1969 Police Science Technical Abstracts and Notes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Police Science Technical Abstracts and Notes, 60 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 272 (1969) This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE JouRNAL OP CRnxniAL LAW, CRnnNoLOGY AND POLICE SCIENCE Vol. 60, No. 2 Copyright @ 1969 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. POLICE SCIENCE TECHNICAL ABSTRACTS AND NOTES Edited by Joseph D. Nicol* Abstractors William E. Kirwant P. J. Cardosill C. R. Turcotte, Jr.** Jan Beck$ P. L. Callaghan S. M. Komartt G. D. McAlvey§ Ordway Hiltontt Quantitative Gas Chromatographic Determi- Method-Carolyn N. Andres, Journal of the nation of Heroin in Illicit Samples-Julian 0. A.O.A.C., 51(5): 1020-1038 (September 1968). Grooms, Journal of the Association of Official Microcrystalline reactions are described for the Analytical Chemistry, 51(5): 1010-1013, (Sep- identification of twelve related phenothiazine- tember 1968). A gas-liquid chromatographic type tranquilizers with six reagents. The drugs method is described for the quantitative deter- tested were promazine, chiorpromazine, triflu- mination of heroin in the presence of opium alka- promazine, mepazine, prochorperazine, triflu- loids such as morphine and monoacetylmorphine, operazine, methoxypromazine, promethazine, pro- and lactose and procaine. -

Psychopharmacologic Therapy 2828 Valerie Levi, Pharm D Deborah Antai-Otong, MS, RN, CNS, PMHNP, CS, FAAN Duane F

Psychopharmacologic Therapy 2828 Valerie Levi, Pharm D Deborah Antai-Otong, MS, RN, CNS, PMHNP, CS, FAAN Duane F. Pennebaker, PhD, FNAP, FRCNA Joy Riley, DNSc, RN, CS CHAPTER OUTLINE The Human Genome and Pharmacology Protein Binding The Brain and Behavior Active Metabolites Neuroanatomical Structures Relevant Cultural Considerations to Behavior Psychopharmacologic Therapeutic Agents Cortical Structures Medication Administration The Cerebral Cortex Antidepressants The Four Lobes and Their Functions Mood Stabilizers The Association Cortices Anticonvulsants The Basal Ganglia Antipsychotics The Hippocampus and the Amygdala Sedatives and Hypnotic Agents Subcortical Structures Psychopharmacologic Therapy across The Brainstem the Life Span The Cerebellum Sedative and Antianxiety Agents The Diencephalon Antipsychotics Neurophysiology and Behavior Children and Adolescents Neurons Antipsychotics Synaptic Transmission Antidepressants Neurotransmitters Mood Stabilizers Biogenic Amines Sedative and Antianxiety Agents Acetylcholine Older Adults Amino Acids Antidepressants Peptides Mood Stabilizers Neurotransmitter Action Sedative and Antianxiety Agents Pharmacokinetic Concepts Antipsychotics Pharmacology The Role of the Nurse Factors That Include Drug Intensity and The Generalist Nurse Duration The Advanced-Practice Psychiatric Absorption Registered Nurse Distribution Treatment Adherence Metabolism Legal and Ethical Issues Elimination Client Advocacy Steady State, Half-Life, and Clearance Steady State Right to Refuse Half-Life Psychoeducation Clearance Medication Monitoring 767 768 UNIT THREE Therapeutic Interventions Competencies Upon completion of this chapter, the learner should be able to: 1. Describe current knowledge about the brain and 4. Explain the nurse’s role in the administration behavior as it relates to the clinical and pharmaco- and prescription of psychopharmacologic agents kinetics of the major psychopharmacologic agents. within the treatment regime. 2. Describe the clinical and pharmacologic proper- 5. -

Impact of Parity

Appendix D. List of Medications for Identifying MH/SA Use and Spending Restricted and expanded Restricted and expanded Major Depressive MH/SA medications Disorder medications 1 = Restricted 1 = Restricted Drug generic name Drug brand name 0 = Expanded* 0 = Expanded** Donepezel Aricept 1 0 Galantamine Reminyl 1 0 Tacrine Cognex 1 0 Rivastigmine Exelon 1 0 Amitriptyline Elavil, Endep, Amitid 1 1 Clomipramine Anafranil 1 1 Desipramine Norpramin, Pertofrane 1 1 Doxepin Sinequan, Zonalon 1 1 Imipramine Tipramine, Tofranil, Tofranil-PM, 1 1 Norfranil Nortriptyline Aventyl, Pamelor 1 1 Protriptyline Vivactil 1 1 Trimipramine Surmontil 1 1 Amoxapine Asendin 1 1 Maprotiline Ludiomil 1 1 Isocarboxazid Marplan 1 1 Meclobemide Aurorix 1 1 Phenelzine Nardil 1 1 Tranylcypromine Parnate 1 1 Citalopram Celexa 1 1 Escitalopram Lexapro 1 1 Fluoxetine Prozac, Sarafem, Prozac Weekly 1 1 Fluvoxamine Luvox 1 1 Paroxetine Paxil 1 1 Sertraline Zoloft 1 1 Bupropion Wellbutrin, Wellbutrin SR 1 1 Mirtazapine Remeron, Remeron SolTab 1 1 Nefazodone Serzone 1 1 Reboxetine Vestra, Edronax 1 1 Venlafaxine Effexor, Effexor XR 1 1 Trazodone Desyrel, Trazolan, Trialodine, 1 1 Dotazone Chlordiazepoxide/amitriptyline Limbitrol, Limbitrol-DS 1 1 Perphenazine/amitriptyline Etrafon, Etrafon-A, Etrafon-Forte, 1 1 Triavil Carbamazepine Atretol, Epitol, Tegretol, Tregetol- 0 0 Evaluation of Parity in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program D-1 Restricted and expanded Restricted and expanded Major Depressive MH/SA medications Disorder medications 1 = Restricted 1 = Restricted -

Special Project

National Mental Health Benchmarking Project Forensic Forum Special Project Seclusion Medication Audit A joint Australian, State and Territory Government Initiative October 2007 National Benchmarking Project - Forensic Forum Seclusion Medication Audit In previous benchmarking work conducted by the National Benchmarking Project – Forensic Forum on reviewing the Australian Council of Health Care Standards (ACHS) seclusion indicators, significant variation in organisational performance was noted. Participants agreed to further explore, in detail, seclusion events. A detailed audit of seclusion was conducted by participating services in late 2006. Discussion of possible reasons for variation identified that there may be differing prescribing patterns of psychotropic medication. The aim of this sub-project was to better understand the reasons for variation in seclusion practices and prescribing patterns across participating organizations Method: Consumer level data to be submitted for each consumer who was an inpatient on 1st November 2005 for acute in-scope services. Same day admissions are not included in this collection. Detailed specifications for this project were developed by the Queensland Mental Health Benchmarking Unit (QMHBU) with advice and endorsement from the National Benchmarking Project Forensic Forum. Formulae for calculation of Chlorpromazine and Benzodiazepine (Valium) equivalent doses are included in the specifications. This report was compiled by the QMHBU on behalf of the National Benchmarking Project – Forensic Forum; it includes the findings of this sub-project. Service Profile A B C D Group Total number of consumers in census 44 43 40 28 155 Average number of days for consumers (Nov) 25 12 27 29 22 Data was collected for 155 consumers. Average length of stay during the month of data collection was the lowest for Org B (12 days), but was similar for the other participating services (25-29 days). -

Discovery of Antiandrogen Activity of Nonsteroidal Scaffolds of Marketed Drugs

Discovery of antiandrogen activity of nonsteroidal scaffolds of marketed drugs W. H. Bisson*, A. V. Cheltsov*, N. Bruey-Sedano†, B. Lin†, J. Chen‡, N. Goldberger‡,L.T.May§¶, A. Christopoulos¶, J. T. Dalton‡, P. M. Sexton¶, X.-K. Zhang†, and R. Abagyan*ʈ *Department of Molecular Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA 92037; †Department of Oncodevelopmental Biology, The Burnham Institute, La Jolla, CA 92037; ‡College of Pharmacy, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210; §Department of Pharmacology, University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia; and ¶Drug Discovery Biology Laboratory, Department of Pharmacology, Monash University, Victoria 3800, Australia Edited by Etienne-Emile Baulieu, Colle`ge de France, Le Kremlin-Bicetre Cedex, France, and approved June 6, 2007 (received for review November 2, 2006) Finding good drug leads de novo from large chemical libraries, real All drugs have activity that is distinct from that elicited by or virtual, is not an easy task. High-throughput screening is often interaction with their primary (or chosen) target. This activity plagued by low hit rates and many leads that are toxic or exhibit generally underlies the side-effect profile of the drug. It is this poor bioavailability. Exploiting the secondary activity of marketed action at secondary or ‘‘off’’ targets that may potentially be drugs, on the other hand, may help in generating drug leads that harnessed for novel drug development, through optimization of can be optimized for the observed side-effect target, while main- the pharmacological profile of the drug to enhance the second- taining acceptable bioavailability and toxicity profiles. Here, we ary activity and effectively eliminate activity at the original describe an efficient computational methodology to discover leads target.