Responding to Welfare Reform in Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Under-Occupying Social Housing: Housing Benefit Entitlement

BRIEFING PAPER Number 06272, 1 November 2019 Under-occupying social By Wendy Wilson housing: Housing Benefit entitlement Inside: 1. Why does under-occupation arise? 2. The rationale for Government intervention 3. Defining under-occupation and who is affected 4. The options for tenants 5. What can landlords do? www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 06272, 1 November 2019 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Why does under-occupation arise? 4 2. The rationale for Government intervention 6 3. Defining under-occupation and who is affected 9 3.1 Continuous entitlement to HB since at least 1 January 1996 9 3.2 How many bedrooms are allowed? 10 3.3 Defining a bedroom 11 Bedroom size 12 Bedrooms used for other purposes 13 3.4 What is working-age? 16 3.5 How much Housing Benefit is lost? 17 3.6 Disabled occupants 18 Overnight care 19 Disabled children sharing a room 21 Disabled adults sleeping in separate rooms 25 Spare rooms and storage of disability related equipment 26 Significantly adapted accommodation 27 3.7 Shared care of children 27 Legal challenges 28 3.8 Sheltered and supported housing 30 3.9 Foster carers and adoptive parents 31 3.10 Temporary absences from home 33 Students 33 Armed forces personnel 34 Legal challenges 35 3.11 Separated couples living together 35 3.12 Bereavement, temporary protection and reporting changes of circumstances 36 4. The options for tenants 37 4.1 Discretionary Housing Payments 37 4.2 Moving to a smaller home 38 4.3 Taking in a lodger 39 4.4 Earning more money 40 5. -

134060 Radius Housing

Case Study What action should you take? Bill and Marie live in a 3 bedroom Radius If you have an extra bedroom/s, you should property with their daughter Lucy, aged 7. think about how the Social Sector Size Criteria / ‘Bedroom Tax’ will apply to your They receive Housing Benefit to help pay household. their rent which is £100 per week. This is • You should consider how you will manage paid to Radius Housing on their behalf. to pay any shortfall. • You could also consider moving to a As they currently under occupy by one smaller property. Your Housing Officer can Social Sector Size bedroom their Housing Benefit is reduced assist you to look at alternative housing by 14%. Thus they have a £14 per week options. Criteria (SSSC) shortfall. • If you require the extra room for care needs you should apply to the NIHE Housing Benefits Section and ask for this to be Bedroom Tax Bill and Marie have to pay the shortfall taken into account when assessing your of £14 per week in their rent to their housing costs. landlord. Help and Support If you are concerned about the ‘Bedroom Tax’ and would like further information or advice, please contact our Welfare Advice Service on Tel 0330 123 0888. Alternatively you can get further information on our website www.radiushousing.org or visit www.nidirect.gov.uk/changes-to- housing-benefit @RadiusHousing /RadiusHousing radiushousing © Radius Housing, May 2019 Registered Office: Radius Housing Association, 38 – 52 Lisburn Road, Belfast BT9 6AA Registered in Northern Ireland (No. IP169), VAT Reg. -

General Election - Housing Policy Update 1

GENERAL ELECTION - HOUSING POLICY UPDATE 1 Briefing note April 2015 GENERAL ELECTION - HOUSING POLICY UPDATE Over recent weeks each of the main parties have released their manifestos, including details of their housing policies, and we set out below highlights from them. Our summary is arranged under key topics and the contrast in policy positions is clear. A coalition or minority government may necessitate compromises to many of these policies and it will be interesting to see which of them are eventually implemented. RIGHT TO BUY Conservative Extend Right to Buy ("RTB") to housing association tenants in England. The replacement of properties to be sold under the scheme to be funded by the sale of expensive Council properties as they fall vacant. Labour Have not outrightly opposed the Conservative RTB proposal but have commented that the potential loss of affordable housing could not work unless it was matched by a "massive Government-led house- building programme". UKIP Apply all revenue from RTB sales (after essential costs) into new community housing and prevent non- British nationals accessing RTB or Help to Buy schemes, unless they have served in HM Armed Forces. Liberal Devolve full control of the RTB scheme to Councils. Democrats Do not support the Conservative proposal to extend RTB scheme to housing association tenants. Green Party End RTB discounts SNP The RTB scheme has already been abolished in Scotland and the SNP have criticised the Conservative proposal to extend the RTB scheme to housing association tenants. Plaid Cymru Have criticised the Conservative proposal to extend the RTB scheme to housing association tenants. -

Accommodation Finder Self Help Pack (PDF, 370

Accommodation finder self-help pack Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Finding a suitable home that you can afford 3 a) Bedroom calculator 3 b) LHA rates in Cheshire West and Chester 3 c) Benefits calculator 4 d) Financial statement 4 3. Choosing the right housing option 4 a) Private rented 4 b) Registered providers (housing associations) 5 c) Council housing 6 d) House shares and room renting 7 e) ‘Forfutures’ supported housing 8 f) Other supported housing 8 g) Lodging 8 h) Buying your own home 9 i) Home swap 10 j) Sheltered and extra care housing 10 4) Homelessness 11 Page 2 1. Introduction This self-help pack can be used by anyone trying to find accommodation in the Cheshire West and Chester area. You can increase your chances of finding something suitable by considering the full range of housing options available to you as well as knowing what you can afford. 2. Finding a suitable home that you can afford It is important that the property you choose is both suitable for your households needs and is affordable. a) Bedroom calculator If you claim Housing Benefit (HB), Universal Credit (UC) or Local Housing Allowance (LHA), it is important that you look for a property with the correct number of bedrooms for your household so that you are not impacted by the ‘Spare Room Subsidy’ (more commonly known as ‘Bedroom Tax’). Even if you don’t currently claim HB, UC or LHA it will be a good idea to do this check in case you need to do so in future. -

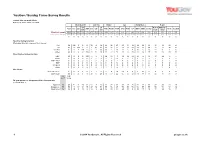

Yougov / Sunday Times Survey Results

YouGov / Sunday Times Survey Results Sample Size: 1903 GB Adults Fieldwork: 12th - 13th September 2013 Voting intention 2010 Vote Gender Age Social grade Region Lib Lib Rest of Midlands Total Con Lab UKIP Con Lab Male Female 18-24 25-39 40-59 60+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland Dem Dem South / Wales Weighted Sample 1903 472 538 129 171 556 490 426 923 980 226 481 651 544 1085 818 244 618 407 468 166 Unweighted Sample 1903 441 586 123 194 554 494 451 884 1019 166 462 751 524 1271 632 280 626 389 464 144 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Headline Voting Intention [Excluding Don't knows and Wouldn't votes] Con 33 100 0 0 0 76 5 13 35 32 32 30 31 40 35 31 30 39 32 33 22 Lab 38 0 100 0 0 3 87 30 37 40 34 42 40 34 36 40 46 26 40 48 35 Lib Dem 9 0 0 100 0 1 1 33 9 10 15 11 8 7 11 7 7 13 7 6 12 Other 20 0 0 0 100 19 6 23 20 19 19 17 22 19 18 22 16 22 21 12 32 Other Parties Voting Intention UKIP 12 0 0 0 100 18 3 10 13 11 6 7 16 13 10 15 9 17 12 10 5 SNP / PCY 3 0 0 0 0 0 2 3 3 3 1 4 2 3 3 2 0 0 2 0 21 Green 3 0 0 0 0 1 0 7 2 4 5 5 3 1 3 2 5 4 3 1 2 BNP 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 3 1 1 0 1 1 2 0 2 1 1 Respect 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 Other 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 2 0 1 0 0 2 1 1 Non Voters Would Not Vote 8 0 0 0 0 3 3 4 7 9 17 11 7 3 8 9 8 12 6 7 4 Don't know 17 0 0 0 0 13 10 25 9 25 22 18 13 21 15 21 18 18 19 17 15 Sep Sep 11-12 12-13 Do you approve or disapprove of the Government's record to date? Approve 31 31 81 5 49 16 62 9 23 37 24 26 29 31 33 33 27 33 33 31 27 25 Disapprove 56 54 8 86 38 73 26 80 62 53 54 41 50 57 57 51 56 52 50 53 56 63 Don't know 13 16 11 8 13 12 13 11 15 10 22 33 20 12 10 15 17 15 17 15 17 12 1 © 2013 YouGov plc. -

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy

Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy Final Report December 2015 Research Report No 913 A report of research carried out by by the Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research and Ipsos MORI on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions. Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department. © Crown copyright 2015. You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. This document/publication is also available on our website at: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-work-pensions/about/ research#research-publications If you would like to know more about DWP research, please email: [email protected] First published December 2015. ISBN 978 1 911003 14 4 Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other Government Department. Evaluation of Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy – Final Report Summary This report presents findings from the evaluation of the Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy (RSRS) undertaken by Ipsos MORI and the Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research. The fieldwork was carried out over the first 20 months of implementation, from April 2013 until November 2014. An interim report was published in July 2014. -

5.2 Relationship Between Benefits and Social Housing (2016)

5.2 Relationship between benefits and social housing There have been a number of major changes to the Housing Benefit Scheme since April 2013. Changes in April 2013 included the introduction of the new under occupation rules that affects tenants living in Social Housing. The amount of Housing Benefit that council tenants and housing association tenants can get if their home is considered too large for their needs has been cut. The rules only affect people of working age (pensioners are not affected). It is commonly referred to as the 'bedroom tax'. Housing Benefit is based on the number of bedrooms a household needs. The new rules allow one bedroom for: a couple (married or unmarried) any person aged 16 or over two children under 16 of the same sex two children aged under 10 regardless of gender any other child (other than a child whose main home is elsewhere) people who need an overnight carer adult children in the Armed Forces (they are treated as living at home even if deployed on operations) disabled children who are unable to share a bedroom with a sibling due to a severe disability. This has meant that tenants may get less help towards rent and service charges if tenants are assessed under these rules as having more bedrooms than the household needs. The rent allowed will be reduced by: 14 per cent if there is one extra bedroom 25 per cent if there are two or more extra bedrooms. The other major change that impacted on housing benefit claimants was the introduction of the Benefit Cap in August 2013. -

Carers UK Briefing on Housing Benefit Size Criteria Rules the Bedroom Tax

Policy Briefing Housing Benefit size criteria rules: the ‘bedroom tax’ January 2013 Summary Housing Benefit is changing and a restriction is being introduced on the number of rooms in a socially rented home which will be covered by Housing Benefit. The new size criteria could have a major impact on certain groups of carers and some families may be unable to cover the shortfall putting them at risk of having to move. Carers UK is particularly concerned that couples where one person is disabled, only one bedroom will be allowed under Housing Benefit rules. This means that a couple who need an extra bedroom for equipment or are unable to sleep in the same room, not be given enough Housing Benefit to cover the extra rent costs of having this room to retain this room. Many homes have been specially adapted, often at a considerable financial cost to local authorities or families themselves. If these families are forced to move, this would be not only distressing for families and disruptive to care arrangements but could risk a greater long-term cost as adaptations need to be replaced in new homes. This note summarises the new rules and looks ahead to further changes on the introduction of Universal Credit later next year. Size criteria rules: what are they? The size criteria rules, have restricted Housing Benefit for private sector tenants for some years. From 1 April 2013 they will also be applied to social sector tenants (people with housing association or local council tenancies for instance). This is commonly referred to as the ‘Bedroom Tax’. -

Adviser Checklist -‐ the Bedroom

Adviser Checklist - The Bedroom Tax Clients living in social sector housing (council, housing association or other social landlord) and who receive Housing BeneFit, will receive a cut in Housing BeneFit iF they have more bedrooms than they are deemed to need. The amount by which HB is reduced is 14% oF the weekly rent For one bedroom, 25% For two or more bedrooms. Does the client in fact have a spare bedroom? Under the social sector rules, one bedroom each is allowed For • Each adult couple (whether married and unmarried, also same sex couples whether in a civil partnership or not) • Any other adult aged 16 or over • Any two children of the same sex aged under 16 • Any two children under the age of 10 • A child • A non-resident carer – if the client is a person who needs overnight care Is the client exempt? The social sector rules do not apply iF: • The client or their partner is at least the qualiFying age For pension credit • Local housing allowance rules or the local reFerence rent rules apply • Shared ownership tenancies • The property is a houseboat, caravan or mobile home • Some temporary accommodation provided by a local authority or registered housing association • The client or their partner/Former partner has been living in the same property and in receipt of Housing BeneFit continuously since 1st January 1996; temporary breaks of up to 4 weeks do not affect exemption, neither do breaks of up to 52 weeks For WelFare to Work recipients. Is the client allowed an additional bedroom? An extra bedroom is allowed in the Following circumstances: • If the client is a foster or kinship carer, providing a child is actually placed with them, or has been [placed with them in the past 52 weeks. -

The Benefit Cap: Public Perceptions and Pre-Implementation Effects

The Benefit Cap: Public perceptions and pre-implementation effects October 2013 Research Report No 850 A report of research carried out by Ipsos MORI on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions © Crown copyright 2013. You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. This document/publication is also available on our website at: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-work-pensions/about/ research#research-publications If you would like to know more about DWP research, please email: [email protected] First published 2013. ISBN 978 1 909532 74 8 Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other Government Department. The Benefit Cap: Public perceptions and pre-implementation effects Summary The Benefit Cap is one of the Government’s most prominent reforms to welfare: Intended as a work incentive, it places a limit on the amount of benefits that out of work households can receive. This quantitative research looked at public attitudes to the Benefit Cap as well as some of the early pre-implementation effects on a specific group of claimants who had received additional Jobcentre Plus support prior to full implementation of the policy. Two different survey methods have been used to gather evidence on these two issues: a nationally representative online survey among 2,017 British adults was used to assess perceptions of the general public and a telephone survey of 500 people identified as ending an out of work benefit claim due to starting a job was used to assess pre-implementation effects. -

Survey Report

YouGov / Sunday Times Survey Results Sample Size: 2078 GB Adults Fieldwork: 17th - 18th July 2014 Westminster VI 2010 Vote Gender Age Social Grade Region Lib Lib Rest of Midlands / Total Con Lab UKIP Con Lab Male Female 18-24 25-39 40-59 60+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland Dem Dem South Wales Weighted Sample 2078 507 600 138 215 614 494 438 1008 1070 247 526 711 594 1184 894 266 675 445 511 181 Unweighted Sample 2078 460 664 125 242 584 545 437 981 1097 199 422 862 595 1381 697 299 575 436 526 242 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Headline Voting Intention [Excluding Wouldn't votes and Don't knows] Con 32 100 0 0 0 74 4 12 29 34 27 25 31 39 34 29 33 37 33 26 21 Lab 37 0 100 0 0 4 82 35 38 37 44 43 40 28 34 42 39 27 41 48 37 Lib Dem 9 0 0 100 0 1 1 33 10 7 10 11 7 8 11 5 13 11 6 7 6 Other 22 0 0 0 100 21 12 20 23 22 19 21 22 25 22 24 15 25 20 20 36 Other Parties Voting Intention UKIP 13 0 0 0 100 17 8 9 14 13 3 10 12 21 12 15 11 16 14 15 5 Green 5 0 0 0 0 2 2 9 4 5 14 4 5 2 5 4 3 7 3 3 4 SNP / PCY 3 0 0 0 0 1 2 2 3 3 2 4 3 2 3 3 0 0 1 1 26 BNP 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 Respect 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Other 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 2 0 1 Non Voters Would Not Vote 8 0 0 0 0 2 1 4 7 8 14 13 5 4 6 10 7 8 7 9 4 Don't know 15 0 0 0 0 13 8 20 13 17 25 15 15 12 14 16 14 15 16 16 13 July July 16-17 17-18 Do you approve or disapprove of the Government’s record to date? Approve 29 29 81 4 45 14 61 7 22 33 25 23 25 28 36 33 24 31 34 30 23 25 Disapprove 56 55 9 87 38 80 27 84 58 55 56 47 55 58 56 52 59 50 50 56 61 64 Don’t know 15 16 10 8 18 6 12 9 20 12 19 31 20 13 8 15 17 18 17 14 16 11 1 © 2014 YouGov plc. -

Ukip 2017 Manifesto

BRITAIN TOGETHER UKIP 2017 MANIFESTO www.ukip.org/manifesto2017 Britain Together Paul Nuttall MEP UKIP Party Leader I have always believed that them down, time and time again. UKIP is at its best when it is You can guarantee that when being radical. It is strongest UKIP says something, we when it is being bold and mean it. leading the political agenda rather than following. This is a unique general election: it is about how the We have done this on Brexit negotiations will be numerous occasions over handled in the years to come the years: when we first said and this makes UKIP more that Britain could not only important than ever before. survive but prosper outside the We are the country’s insurance European Union, the political policy, the guard dogs of Brexit. class laughed at us. When we We have fought for Brexit all our spoke of the need for a points- political lives and we want to based system for migrants If you believe in Britain, ensure that the people get the we were derided as racists kind of Brexit they voted for on if you believe in our values, and xenophobes by the same 23rd June last year. and if you believe in real people. This is now government policy for non-EU migrants. This does not mean we just Brexit, then vote UKIP control immigration and reduce on 8th June. In many ways, UKIP was a the numbers of people coming decade ahead of its time to our country. It means we are on these issues and in this not saddled with a huge divorce manifesto UKIP is once again bill, we reclaim our waters, and setting the agenda.