INSAF Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

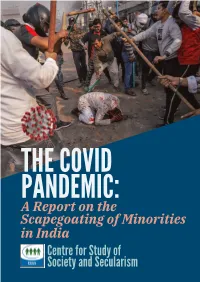

THE COVID PANDEMIC: a Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism I

THE COVID PANDEMIC: A Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism i The Covid Pandemic: A Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism Mumbai ii Published and circulated as a digital copy in April 2021 © Centre for Study of Society and Secularism All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including, printing, photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher and without prominently acknowledging the publisher. Centre for Study of Society and Secularism, 603, New Silver Star, Prabhat Colony Road, Santacruz (East), Mumbai, India Tel: +91 9987853173 Email: [email protected] Website: www.csss-isla.com Cover Photo Credits: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters iii Preface Covid -19 pandemic shook the entire world, particularly from the last week of March 2020. The pandemic nearly brought the world to a standstill. Those of us who lived during the pandemic witnessed unknown times. The fear of getting infected of a very contagious disease that could even cause death was writ large on people’s faces. People were confined to their homes. They stepped out only when absolutely necessary, e.g. to buy provisions or to access medical services; or if they were serving in essential services like hospitals, security and police, etc. Economic activities were down to minimum. Means of public transportation were halted, all educational institutions, industries and work establishments were closed. -

The Lockdown to Contain the Coronavirus Outbreak Has Disrupted Supply Chains. One Crucial Chain Is Delivery of Information and I

JOURNALISM OF COURAGE SINCE 1932 The lockdown to contain the coronavirus outbreak has disrupted supply chains. One crucial chain is delivery of information and insight — news and analysis that is fair and accurate and reliably reported from across a nation in quarantine. A voice you can trust amid the clanging of alarm bells. Vajiram & Ravi and The Indian Express are proud to deliver the electronic version of this morning’s edition of The Indian Express to your Inbox. You may follow The Indian Express’s news and analysis through the day on indianexpress.com DAILY FROM: AHMEDABAD, CHANDIGARH, DELHI, JAIPUR, KOLKATA, LUCKNOW, MUMBAI, NAGPUR, PUNE, VADODARA JOURNALISM OF COURAGE SATURDAY, AUGUST 29, 2020, NEW DELHI, LATE CITY, 18 PAGES SINCE 1932 `6.00 (`8 PATNA &RAIPUR, `12 SRINAGAR) WWW.INDIANEXPRESS.COM SC backs UGC decision to holdexams, CHANGE IN LAW DISCUSSED saysstates can seek deadline extension PMOexplores (UGC) forextension of the terminalsemesterexamination ANANTHAKRISHNANG September 30 deadline. JEE-NEET:6OPP by 30.09.2020 in exercise of commonvoter NEWDELHI,AUGUST28 Maharashtraand Delhihad powerunderDisasterManage- earlier decidedtocancel the ex- STATESSEEKREVIEW ment Act, 2005 shall prevail over THE SUPREME CourtFriday ruled ams and promote studentson OPPOSITION-RULED deadline" fixedbythe UGC“in Lok Sabha Speaker Om Birla holds ameeting aheadofthe that universitiesand other insti- the basis of otherparameters. West Bengal, Jharkhand, respect to the concernedState”. Parliamentsession, in NewDelhi on Friday. ANI tutions of higher education will AbenchofJustices Ashok Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, The courtwas clear that the listforLS,state have to conduct the final-yearex- Bhushan,RSubhashReddyandM Punjab and Maharashtra “decisionofthe State/State ams and “cannot” promote stu- RShah“refused”toquashtheJuly have movedthe DisasterManagement Authority dentsonthe basisofinternalas- 6UGCguidelinesaskinguniversi- SupremeCourt seekinga to promote the studentsinthe SpeakerasksHouse sessment or othercriteria. -

Fatal, Not Funny: Nationalist Outrage & Journalists Against Journalists

Essay Fatal, not Funny: Nationalist Outrage & Journalists against Journalists VIDYA SUBRAHMANIAM India’s dyed-in-the wool ‘nationalist’ TV channels have made it clear that even as they rage against Pakistan, they will also hunt down anyone defying the agenda to counsel peace between India and Pakistan. Vidya Subrahmaniam, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, New Delhi, captures the frenzy that overtook the TV media in the wake of the Pulwama attack and warns of the dangers inherent in allowing a free run to the stirred up faux nationalism that has already turned journalist against journalist. lot has been written about the daily battle scenes enacted in Indian television studios by flag-waving nationalist anchors, some of them A clothed in combat fatigues just in case viewers mistook the stomping of feet and waving of hands for a dance show. Following the killing of 40 jawans in a terrorist attack on a Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) convoy in the Kashmir valley, TV voices had grown shriller and shriller. The call for action was not just against terrorists operating from Pakistan’s soil, but also for taking out Pakistan, to erase it off the map. From Republic TV and Times Now to the full range of Hindi news channels, the studios had been turned into war rooms to cries of Pakistan ko mita denge (we will wipe out Pakistan). No journalist worth her salt could be unfamiliar with the Prime Time drill, as the hazards of surfing the news channels came with the territory. The staple consisted of anchors getting enraged over something or the other that required the Opposition and liberal citizens to be pummelled, even if, or especially if, it was the government The raging against Pakistan seemed to go hand in hand with a magnificent self- that had been up to no good. -

The Contagion of Hate in India

THE CONTAGION OF HATE IN INDIA By Laxmi Murthy Laxmi Murthy is a journalist based in Bangalore, India. Introduction The COVID-19 pandemic that began its sweep This paper attempts to understand the pheno- across the globe in early 2020 has had a menon of hate speech and its potential to devastating effect not only on health, life legitimise discrimination and promote violence and livelihoods, but on the fabric of society against its targets. It lays out the interconnections itself. As with all moments of social crisis, it between Islamophobia, hate speech and acts has deepened existing cleavages, as well as of physical violence against Muslims. The role dented and even demolished already fragile of social media, especially messaging platforms secular democratic structures. While social and like WhatsApp and Facebook, in facilitating economic marginalisation has sharpened, one the easy and rapid spread of fake news and of the starkest consequences has been the rumours and amplifying hate, is also examined. naturalisation of hatred towards India’s largest The complexities of regulating social media minority community. Along with the spread platforms, which have immense political and of COVID-19, Islamophobia spiked and spread corporate backing, have been touched upon. rapidly into every sphere of life. From calls to This paper also looks at the contentious and marginalise,1 isolate,2 segregate3 and boycott contradictory interplay of hate speech with the Muslim communities, to sanctioning the use of constitutionally guaranteed freedom of speech force, hateful prejudice peaked and spilled over and expression and recent jurisprudence on these into violence. An already beleaguered Muslim matters. -

Mother of All Bombs’ Jadhav Chargesheet MPOST BUREAU Access to Jadhav So That We Can Appeal," He Said

millenniumpost.in RNI NO.: WBENG/2015/65962 PUBLISHED FROM DELHI & KOLKATA VOL. 3, ISSUE 101 | Saturday, 15 April 2017 | Kolkata | Pages 16 | Rs 3.00 NO HALF TRUTHS AD ROW: SHAPOORJI 5 HELD FOR N KOREA CONDEMNS WHEN PALLONJI FLOUTS ASSAULTING CRPF MEN, US FOR BRINGING HRITHIK ROSHAN REAL ESTATE NEW VIDEOS SPARK ‘HUGE’ NUKE ASSETS ALMOST GAVE UP REGULATIONS PG3 FRESH ROW PG6 TO REGION PG10 IN LIFE PG16 Quick News44 THE US DROPPED BIGGEST NON-NUCLEAR BOMB AT 7.30 PM ON THURSDAY TARGETING ISIS CAVES PAK SAYS IT HAS CREDIBLE EVIDENCE Imposing only fine India demands copy of on woman convict in ‘Mother of all bombs’ Jadhav chargesheet MPOST BUREAU access to Jadhav so that we can appeal," he said. serious case unfair: SC ISLAMABAD/NEW Sources in New kills 36 ISIS militants DELHI: India on Fri- Delhi said apart from NEW DELHI: The Supreme Court has held KABUL: The attack on a tunnel day demanded from diplomatic options, that imposing only a fine in serious offences, complex in remote eastern Afghan- What is the MOAB bomb? Pakistan a certified India will also explore which entail award of jail terms and fine both, istan with the largest non-nuclear » The GBU-43/B Massive Ordnance Air Blast copy of the charge- legal remedies per- on women convicts would lead to “unfair” weapon ever used in combat by (MOAB) is a 21K-pound, GPS-guided explosive sheet as well as the mitted under Pakistan and “unjust” consequences. Observing this, the US military left 36 Islamic State judgement in the death sen- legal system including Jadhav's the apex court set aside the Himachal Pradesh group fighters dead and no civil- » This is the first time that the US has used the tence of its national Kulb- family appealing against the High Court verdict imposing only a fine on a ian casualties, Afghanistan officials MOAB bomb in combat hushan Jadhav and sought verdict. -

A Comparative Study of Pakistani & Indian English

Araştırma Makalesi (Research Article) A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PAKISTANI & INDIAN ENGLISH DAILIES EDITORIALS ON THE COVERAGE OF DETERIORATING CONDITIONS OF INDIAN MUSLIMS Muhammad FAHİM Riphah International University, Pakistan [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4342-3068 Fahim, M. (2021). A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PAKISTANI & INDIAN ENGLISH DAILIES EDITORIALS ON THE COVERAGE OF Atıf DETERIORATING CONDITIONS OF INDIAN MUSLIMS. İstanbul Aydın Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 13(2), 501-532 ABSTRACT This research examines the stance/slant and the magnitude of media coverage given to the deteriorating conditions of Indian Muslims. Minorities in India, especially the Indian Muslims, enduring an institutional and systematic bias and neglect in all walks of life. Though the Indian constitution bestows equal rights to all its subjects, however, the ground reality is telling completely an opposite story. The Indian Muslims fell victim to communal violence myriads of times since the inception of modern India. Moreover, since Modi’s assertion into the throne, the situation worsened. The purpose of this research was to examine the stance/slant and the magnitude of media coverage given to the deteriorating conditions of Indian Muslims. Two Indian (Times of Indian & Hindustan Time) and two Pakistani (Dawn & The Nation) English dailies were selected for this study based on their circulation and influence in public and the power corridors. The method of content analysis was castoff to fulfill the needs of the study. Six months (Aug 11, 2019, to Feb 11, 2020) of editorial coverage of the said dailies were examined through content analysis. A total of 57 editorials were found published about the deteriorating conditions of Indian Muslims and were examined through content analysis. -

Mother of All Bombs’ Jadhav Chargesheet MPOST BUREAU MPOST BUREAU Access to Jadhav So That NEW DELHI: the Income Tax Department Has We Can Appeal," He Said

RNI NO.: DELENG/2005/15351 millenniumpost.in REGD. NO.: DL(S)-01/3420/2015-17 PUBLISHED FROM DELHI & KOLKATA VOL. 12, ISSUE 103 | Saturday, 15 April 2017 | New Delhi | Pages 16 | Rs 3.00 NO HALF TRUTHS AAP TO FOCUS ON 5 HELD FOR N KOREA CONDEMNS WHEN ‘POSITIVE’ ISSUES ASSAULTING CRPF MEN, US FOR BRINGING HRITHIK ROSHAN INSTEAD OF ATTACKING NEW VIDEOS SPARK ‘HUGE’ NUKE ASSETS ALMOST GAVE UP PM MODI PG3 FRESH ROW PG6 TO REGION PG10 IN LIFE PG16 I-T launches ‘Op Clean THE US DROPPED BIGGEST NON-NUCLEAR BOMB AT 7.30 PM ON THURSDAY TARGETING ISIS CAVES PAK SAYS IT HAS CREDIBLE EVIDENCE Money’-II: 60,000 people India demands copy of under I-T scanner ‘Mother of all bombs’ Jadhav chargesheet MPOST BUREAU MPOST BUREAU access to Jadhav so that NEW DELHI: The Income Tax department has we can appeal," he said. identified over 60,000 “high risk” persons for a ISLAMABAD/NEW Sources in New probe under the second phase of the ‘Opera- kills 36 ISIS militants DELHI: India on Fri- Delhi said apart from tion Clean Money’ which was launched Thurs- KABUL: The attack on a tunnel day demanded from diplomatic options, day to detect black money generation post complex in remote eastern Afghan- What is the MOAB bomb? Pakistan a certified India will also explore demonetisation. istan with the largest non-nuclear » The GBU-43/B Massive Ordnance Air Blast (MOAB) copy of the charge- legal remedies per- The CBDT said the category of people who weapon ever used in combat by is a 21K-pound, GPS-guided explosive sheet as well as the mitted under Pakistan will undergo “detailed investigations” as part of the US military left 36 Islamic State judgement in the death sen- legal system including Jadhav's the next phase of the operation include busi- group fighters dead and no civil- » This is the first time that the US has tence of its national Kulb- family appealing against the nesses claiming cash sales as the source of cash ian casualties, Afghanistan officials used the MOAB bomb in combat hushan Jadhav and sought verdict. -

Hit Job: Using COVID-19 to Deepen Anti-Muslim Bias and Weaken

HIT JOB Using COVID-19 to HITDeepen Anti-Muslim JOB Bias and Weaken Muslim Voice In Association With Using COVID-19 to Deepen Anti-Muslim Bias and Weaken Muslim Voice JUSTICE & EQUALITY FORUM Hit Job, - Page: 1 Citizens Against Hate (CAH) is a collective of individuals and groups committed to a democratic, secular and caring India. It is an open collective, with members drawn from a wide range of backgrounds who are concerned about the growing hold of exclusionary tendencies in society, and the weakening of rule of law. CAH was formed in 2017, in response to the rising trend of hate and vigilante violence, to document violations, provide support to survivors, and engage with institutions for improved justice and policy reforms. Since, we have also worked on other forms of violations – hate speech, sexual violence and state violence, and citizenship rights among others in Assam, Bihar, Haryana, Kashmir, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. Our approach to addressing the justice challenge facing particularly vulnerable communities is through research, outreach and advocacy; and to provide practical help to survivors in their struggles, also helping them to become agents of change. http://citizensagainsthate.org/ Justice and Equality Forum (JEFOR) is a network of researchers and activists pursuing justice for victims of discrimination and violence and seeking to build inclusive societies founded on principles of equality. Members of the research and writing team included Abhimanyu Suresh, Adeela Firdous, Misbah Reshi, Sajjad Hassan and Salim Ansari. Ghazala Jamil, Mathew Jacob, Seema Nair and Shikha Dilawri provided valuable guidance. Design and Layout by: http://www.mediabravo.com Cover page picture credits (clock-wise from top left): PTI (31 March, 2020), Reuters/Adnan Abidi (25 March, 2020), Reuters/Danish Siddiqui (26 March, 2020), IANS (26 January, 2020), Getty Images (19 April, 2020), Reuters/Francis Mascarenhas (11 April, 2020). -

Nationalist Outrage & Journalists Against

Part 1 Essay Fatal, not Funny: Nationalist Outrage & Journalists against Journalists VIDYA SUBRAHMANIAM India’s dyed-in-the wool ‘nationalist’ TV channels have made it clear that even as they rage against Pakistan, they will also hunt down anyone defying the agenda to counsel peace between India and Pakistan. Vidya Subrahmaniam, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, New Delhi, captures the frenzy that overtook the TV media in the wake of the Pulwama attack and warns of the dangers inherent in allowing a free run to the stirred up faux nationalism that has already turned journalist against journalist. lot has been written about the daily battle scenes enacted in Indian television studios by flag-waving nationalist anchors, some of them A clothed in combat fatigues just in case viewers mistook the stomping of feet and waving of hands for a dance show. Following the killing of 40 jawans in a terrorist attack on a Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) convoy in the Kashmir valley, TV voices had grown shriller and shriller. The call for action was not just against terrorists operating from Pakistan’s soil, but also for taking out Pakistan, to erase it off the map. From Republic TV and Times Now to the full range of Hindi news channels, the studios had been turned into war rooms to cries of Pakistan ko mita denge (we will wipe out Pakistan). No journalist worth her salt could be unfamiliar with the Prime Time drill, as the hazards of surfing the news channels came with the territory. -

Crux of the Hindu and PIB Vol 73

aspirantforum.com News of SeptemberTHE CRUX 2020 OF THE HINDU AND PIB THE CRUX OF THE HINDU AND THE PIB Vol. 73 SEPTEMBERImportant News In the Field oF 2020 VOL.73National Economy Internatioonal India and the World Science, Tech and Environment Misclleneous News aspirantforum.com Aspirant Forum AN INITIATIVE BY UPSC ASPIRANTS Visit aspirantforum.com for Guidance and Study Material for IAS Exam aspirantforum.com THE CRUX OF THE HINDU AND PIB SEPTEMBER Aspirant Forum is a Community for the SEPTEMBER 2020 2020 UPSC Civil Services (IAS) Aspirants, VOL.73 VOL.73 to discuss and debate the various things related to the exam. We welcome an active participation from the fellow members to Editorial Team: enrich the knowledge of all PIB Compilation: Nikhil Gupta The Hindu Compilation: The Crux will be published online Shakeel Anwar for free on 10th of every month. Shahid Sarwar We appreciate the friends and Karuna Thakur followers for apprepreciating our Designed by: effort. For any queries, guidance Anupam Rastogi needs and support, Please contact at: [email protected] You may also follow our website Aspirantforum.com for free online coaching and guidance for IAS Visit aspirantforum.com for Guidance and Study Material for IAS Exam aspirantforum.com THE CRUX OF THE HINDU AND PIB Contents SEPTEMBER 2020 VOL.73 National News..................5 Economy News...............61 International News.........131 India and the World........177 Science and Technology + aspirantforum.com Environment..................aspirantforum.com228 Miscellaneous News an Events............................276 Visit aspirantforum.com for Guidance and Study Material for IAS Exam aspirantforum.com THE CRUX OF THE HINDU AND PIB About the ‘CRUX’ SEPTEMBER 2020 Introducing a new and convenient product, to help the aspirants for the various public services examinations. -

List of Permitted Private Satellite TV Channels As on 19.01.2012 Sr

List of Permitted Private Satellite TV Channels as on 19.01.2012 Sr. CHANNEL DATE OF DATE OF TYPE COMPANY ADDRESS TELEPHONE UPLINK/ LANGUAGE BOARD OF DIRECTOR OPERAT No. NAME APPLICATIO PERMISSIO OF NAME NO. DOWNLI IONAL N N CHANN K/UPLIN STATUS (MM/DD/Y EL K Y) ONLY/D OWNLIN K ONLY 1 AAJ TAK 10/10/2000 04/12/2000 NEWS TV TODAY 201,COMPETE 011- UL&DL Hindi Ms. Koel Purie, Ms. Anil Vig, Ms. YES NETWORK NT HOUSE, F- 23684888 Bala Deshpande, Mr. Ranjan B Mittal LIMITED 14,MIDDLE & Mr. Anil Mehra (Shri Rajeev CIRCLE, Thakore & Shri Rakesh Kumar CONNAUGHT Malhotra appointed on 10.01.2005, PLACE NEW Ms. Aroon Purie Rinchet) DELHI-110001 2 JAIN TV 01/11/2000 04/01/2001 NEWS JAIN TV SCINDIA 011- UPLINK HINDI/ENG Dr.J.K. JAIN. ANKUR JAIN, Dr RAGINI YES VILLA,RING 26874046 & LISH JAIN, T.N.CHARTURVEDI, ROAD, DOWNLI B.D.DIKSHIT, P.N.LEKHI, MURLI DHAR SAROJANI NK ASTHANA, Dr SHEKHAR AGARWAL, NAGAR, NEW KAMAL FARUQUI DELHI-110023 3 ADITHYA 21/10/2000 26/03/2001 NEWS SUN TV Murasoli 044- UPLINK English & Mr. Kalanithi Maran, Mrs. Kaveri YES TV NETWORK Maran 44676767, & All Indian Kalanithi, Mr. S Sridharan, Mr. M.K. LIMITED Towers, 73, 044- DOWNLI Languages Harinarayanan, Mr. S. Selvam, Mr. J MRC Nagar 40676161 NK Ravidharan & Mr. Nicholas Martin Main Road, Paul MRC Nagar, Chennai - 600028 List of Permitted Private Satellite TV Channels as on 19.01.2012 Sr. CHANNEL DATE OF DATE OF TYPE COMPANY ADDRESS TELEPHONE UPLINK/ LANGUAGE BOARD OF DIRECTOR OPERAT No.