ON 22(4) 601-614.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2016 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Sophie Wolbert SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Wolbert, Sophie, "Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides" (2016). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2470. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2470 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wolbert 1 Trends in Nectar Concentration and Hummingbird Visitation: Investigating different variables in three flowers of the Ecuadorian Cloud Forest: Guzmania jaramilloi, Gasteranthus quitensis, and Besleria solanoides Author: Wolbert, Sophie Academic -

List of the Birds of Peru Lista De Las Aves Del Perú

LIST OF THE BIRDS OF PERU LISTA DE LAS AVES DEL PERÚ By/por MANUEL A. -

Birding in Southern Ecuador February 11 – 27, 2016 TRIP REPORT Folks

Mass Audubon’s Natural History Travel and Joppa Flats Education Center Birding in Southern Ecuador February 11 – 27, 2016 TRIP REPORT Folks, Thank you for participating in our amazing adventure to the wilds of Southern Ecuador. The vistas were amazing, the lodges were varied and delightful, the roads were interesting— thank goodness for Jaime, and the birds were fabulous. With the help of our superb guide Jose Illanes, the group managed to amass a total of 539 species of birds (plus 3 additional subspecies). Everyone helped in finding birds. You all were a delight to travel with, of course, helpful to the leaders and to each other. This was a real team effort. You folks are great. I have included your top birds, memorable experiences, location summaries, and the triplist in this document. I hope it brings back pleasant memories. Hope to see you all soon. Dave David M. Larson, Ph.D. Science and Education Coordinator Mass Audubon’s Joppa Flats Education Center Newburyport, MA 01950 Top Birds: 1. Jocotoco Antpitta 2-3. Solitary Eagle and Orange-throated Tanager (tied) 4-7. Horned Screamer, Long-wattled Umbrellabird, Rainbow Starfrontlet, Torrent Duck (tied) 8-15. Striped Owl, Band-winged Nightjar, Little Sunangel, Lanceolated Monklet, Paradise Tanager, Fasciated Wren, Tawny Antpitta, Giant Conebill (tied) Honorable mention to a host of other birds, bird groups, and etc. Memorable Experiences: 1. Watching the diving display and hearing the vocalizations of Purple-collared Woodstars and all of the antics, colors, and sounds of hummers. 2. Learning and recognizing so many vocalizations. 3. Experiencing the richness of deep and varied colors and abundance of birds. -

Practical-Actions-Report.Pdf

CONTENIDO I.- INTRODUCCIÓN ........................................................................................................................ 5 II. OBJETIVOS DEL ESTUDIO .......................................................................................................... 6 III.- UBICACIÓN DEL ÁREA DE ESTUDIO ....................................................................................... 6 III.- MARCO REFERENCIAL ............................................................................................................ 9 IV.- MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS .................................................................................................... 12 4.1. MATERIALES ..................................................................................................................... 12 4.2. MÉTODOS ........................................................................................................................ 14 4.2.1. ANÁLISIS CARTOGRÁFICO DE LA ZONA ................................................................... 14 4.2.2. PRESENCIA DE ESPECIES CLAVE ................................................................................ 16 4.2.3. IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LA DIETA DE LAS ESPECIES CLAVE .......................................... 28 4.2.4. CAPACITACIÓN A GUÍA LOCALES ............................................................................. 29 5.1. PRESENCIA DE ESPECIES CLAVE ....................................................................................... 31 5.1.1. Determinación de presencia mediante -

Northern Peru Endemics

Northern Peru Endemics With Naturalist Journeys & Caligo Ventures July 8 – 18, 2019 866.900.1146 800.426.7781 520.558.1146 [email protected] www.naturalistjourneys.com or find us on Facebook at Naturalist Journeys, LLC Naturalist Journeys, LLC | Caligo Ventures PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 PH: 520.558.1146 | 800.426.7781 Fax 650.471.7667 naturalistjourneys.com | caligo.com [email protected] | [email protected] Explore Northern Peru on this Naturalist Journeys tour, a jigsaw of Andean mountains and deeply sliced Tour Highlights canyons, for a treasure trove of landscapes and birds. ✓ Observe the stunning Marvelous Spatuletail, arguably the most beautiful Recent upgrades in infrastructure and new lodges have hummingbird in the world, along with over opened up this region as a major birding destination 40 other species including Royal Sunangel, that can be explored in relative comfort. This tour Rainbow Starfrontlet, and Emerald-bellied supports local communities as they develop viable Puffleg ecotourism in the area. ✓ Sample Peru’s culinary delights, now famous around the world, such as chicha The isolating effects of the jagged Andes are nowhere morada and causa rellena more apparent than in northern Peru, where the ✓ Wonder at the Kuelap Archaeological Site, dramatic topography creates extreme habitat contrasts an outstanding pre-Incan ruin constructed — from tropical rainforests and arid valleys to high by the Chachapoyas culture paramo and lowland swamps. On this tour, we visit the ✓ Seek the Long-whiskered Owlet, a mythical dry Marañon Valley, an awesome canyon carved by a denizen of stunted high elevation forest, major tributary of the Amazon and a formidable barrier first mist-netted on the night of August 23, 1976 to the distribution of Andean birds. -

The Conservation Status of Birds on the Cordillera De Colan, Peru

Bird Conservation International (1997) 7:181-195. © BirdLife International 1997 The conservation status of birds on the Cordillera de Colan, Peru C. W. N. DAVIES, R. BARNES, S. H. M. BUTCHART, M. FERNANDEZ and N. SEDDON Summary In July and August 1994, we surveyed two areas in the south of the Cordillera de Colan, Amazonas department, Peru, above the north bank of the rio Utcubamba. We found a high rate of deforestation, with trees being felled for timber, forest being cleared for the cultivation of cash crops, and elfin forest being burned for pasture. Most of the forest on the mountain range may have been cleared in 10 years. We recorded a number of important bird species, highlighting the significance of the area for the conservation of biodiversity; globally threatened birds included Peruvian Pigeon Columba oenops, Military Macaw Am militaris and Royal Sunangel Heliangelus regalis. Elfin forest is under particular threat in the area, but probably still holds species such as Long-whiskered Owlet Xenoglaux lowcryi. We recommend that a protected area containing areas of cloud-forest and elfin forest be established on the Cordillera de Colan. Introduction The Andean mountain chain is one of the most biologically diverse areas of the world. ICBP (1992) identified 23 Endemic Bird Areas (EBAs) in the Andes, reflecting a pattern of endemism corresponding well with data on other animal and plant groups (ICBP 1992). The tropical Andes must be considered a high priority for conservation, because of their high biodiversity and severe environmental degradation. In Peru, there are several large effectively protected areas of wet montane forest in the south and centre the country, the northernmost being Rio Abiseo National Park centred at 8°S, but the only protected area of wet montane forest in the north is the Alto Mayo Protection Forest which aims at watershed rather than biological resource conservation (INRENA 1995). -

La Perla Acquisition, Abra Patricia Reserve in Peru

La Perla Acquisition, Abra Patricia Reserve in Peru A Tropical Forest Forever Fund Grant Continuing with our efforts to protect wintering grounds for nearctic/neotropical migrants, our Tropical Forest Forever Fund,awarded a grant of $25,000 to American Bird Conservancy and ECOAN to acquire a significant forest addition to the Abra Patricia Reserve in Peru: the La Perla tract (shown in red on the map below). The Abra Patricia-Alto Nieva Private Conservation Area is located at mid- altitude in the foothills of the Andes, in the Peruvian Yungas where bird diversity is among the highest on Earth. The reserve protects parts of the upper watershed and headwaters of the Amazon River which is threatened by accessibility through a major paved road as well as the construction of new roads, bringing logging, agriculture, and cattle ranching as well as poaching of wildlife and orchids. A total of 6,690 acres has been acquired for this reserve to protect habitat for migratory and threatened bird species including the endangered Long-Whiskered Owlet and the Ochre-fronted Antpitta. The reserve is owned and managed by ECOAN, the Andean Ecosystem Association which works to conserve birds and other wildlife and their ecosystems in the Andes of Peru. The American Bird Conservancy and ECOAN are in the final stages of acquiring the core tracts of forest needed to complete the Abra Patricia Reserve and the 86- acre La Perla tract is a significant addition. It is located on the southern edge of the reserve and has about 60% forest cover. The World Bank and World Wildlife Fund rank the Peruvian Yungas ecoregion among the richest ecosystems in the world with at least 7,000 species of flowering plants and an exceptional concentration of endemic plant and animal species. -

Northern Peru Marañon Endemics & Marvelous Spatuletail 4Th to 25Th September 2016

Northern Peru Marañon Endemics & Marvelous Spatuletail 4th to 25th September 2016 Marañón Crescentchest by Dubi Shapiro This tour just gets better and better. This year the 7 participants, Rob and Baldomero enjoyed a bird filled trip that found 723 species of birds. We had particular success with some tricky groups, finding 12 Rails and Crakes (all but 1 being seen!), 11 Antpittas (8 seen), 90 Tanagers and allies, 71 Hummingbirds, 95 Flycatchers. We also found many of the iconic endemic species of Northern Peru, such as White-winged Guan, Peruvian Plantcutter, Marañón Crescentchest, Marvellous Spatuletail, Pale-billed Antpitta, Long-whiskered Owlet, Royal Sunangel, Koepcke’s Hermit, Ash-throated RBL Northern Peru Trip Report 2016 2 Antwren, Koepcke’s Screech Owl, Yellow-faced Parrotlet, Grey-bellied Comet and 3 species of Inca Finch. We also found more widely distributed, but always special, species like Andean Condor, King Vulture, Agami Heron and Long-tailed Potoo on what was a very successful tour. Top 10 Birds 1. Marañón Crescentchest 2. Spotted Rail 3. Stygian Owl 4. Ash-throated Antwren 5. Stripe-headed Antpitta 6. Ochre-fronted Antpitta 7. Grey-bellied Comet 8. Long-tailed Potoo 9. Jelski’s Chat-Tyrant 10. = Chestnut-backed Thornbird, Yellow-breasted Brush Finch You know it has been a good tour when neither Marvellous Spatuletail nor Long-whiskered Owlet make the top 10 of birds seen! Day 1: 4 September: Pacific coast and Chaparri Upon meeting, we headed straight towards the coast and birded the fields near Monsefue, quickly finding Coastal Miner. Our main quarry proved trickier and we had to scan a lot of fields before eventually finding a distant flock of Tawny-throated Dotterel; we walked closer, getting nice looks at a flock of 24 of the near-endemic pallidus subspecies of this cracking shorebird. -

Reversed Plumage Ontogeny in a Female Hummingbird: Implications for the Evolution of Iridescent Colours and Sexual Dichromatisrn

Biological Journal ofthe Linnean Society (1992), 47: 183-195. With 3 figures Reversed plumage ontogeny in a female hummingbird: implications for the evolution of iridescent colours and sexual dichromatisrn ROBERT BLEIWEISS Department of <ooLog~ and the zoological Museum, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A. Received 15 Nouember 1990, accepted for publication 18 April 1991 In polygynous birds, bright plumage is typically more extensive in the sexually competitive males and develops at or after sexual maturity. These patterns, coupled with the importance of male plumage in sexual displays, fostered the traditional hypothesis that bright plumages and sexual dichromatism develop through the actions of sexual selection on males. This view remains problematic for hummingbirds, all of which are polygynous, because their bright iridescent plumages are also important non-sexual signals associated with dominance at floral nectar sources. Here I show that female amethyst-throated sunangels [Heliangelus amethysticollis (d’Orbigny & Lafresnaye)], moult from an immature plumage with an iridescent gorget to an adult plumage with a non-iridescent gorget. This ‘reversed’ ontogeny contradicts the notion that iridescent plumage has a sexual function because sexual selection in polygynous birds should be lowest among non- reproductive immature females. Moreover, loss of iridescent plumage in adult females indicates that adult sexual dichromatism in H. amethysticolfzs is due in large part to changes in female ontogeny. I suggest that both the ontogeny and sexual dichromatism evolved in response to competition for nectar KEY WORDS:-Hummingbird - moult - ontogeny - iridescence - sexual selection - feeding ecology. CONTENTS Introduction ................... 183 Materials and methods ................ 184 Results .................... 186 Sexing ................... 186 Age and gonad condition .............. -

Supporting References for Nelson & Ellis

Supplemental Data for Nelson & Ellis (2018) The citations below were used to create Figures 1 & 2 in Nelson, G., & Ellis, S. (2018). The History and Impact of Digitization and Digital Data Mobilization on Biodiversity Research. Publication title by year, author (at least one ADBC funded author or not), and data portal used. This list includes papers that cite the ADBC program, iDigBio, TCNs/PENs, or any of the data portals that received ADBC funds at some point. Publications were coded as "referencing" ADBC if the authors did not use portal data or resources; it includes publications where data was deposited or archived in the portal as well as those that mention ADBC initiatives. Scroll to the bottom of the document for a key regarding authors (e.g., TCNs) and portals. Citation Year Author Portal used Portal or ADBC Program was referenced, but data from the portal not used Acevedo-Charry, O. A., & Coral-Jaramillo, B. (2017). Annotations on the 2017 Other Vertnet; distribution of Doliornis remseni (Cotingidae ) and Buthraupis macaulaylibrary wetmorei (Thraupidae ). Colombian Ornithology, 16, eNB04-1 http://asociacioncolombianadeornitologia.org/wp- content/uploads/2017/11/1412.pdf [Accessed 4 Apr. 2018] Adams, A. J., Pessier, A. P., & Briggs, C. J. (2017). Rapid extirpation of a 2017 Other VertNet North American frog coincides with an increase in fungal pathogen prevalence: Historical analysis and implications for reintroduction. Ecology and Evolution, 7, (23), 10216-10232. Adams, R. P. (2017). Multiple evidences of past evolution are hidden in 2017 Other SEINet nrDNA of Juniperus arizonica and J. coahuilensis populations in the trans-Pecos, Texas region. -

Bioone COMPLETE

BioOne COMPLETE Introduction to the Skeleton of Hummingbirds (Aves: Apodiformes, Trochilidae) in Functional and Phylogenetic Contexts Author: Zusi, Richard L., Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 37012, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20013, USA Source: Ornithological Monographs No. 77 Published By: American Ornithological Society URL: https://doi.org/10.1525/om.2013.77.L1 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne's Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/ebooks on 1/14/2019 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by University of New Mexico Ornithological Monographs Volume (2013), No. 77, 1-94 © The American Ornithologists' Union, 2013. Printed in USA. INTRODUCTION TO THE SKELETON OF HUMMINGBIRDS (AVES: APODIFORMES, TROCHILIDAE) IN FUNCTIONAL AND PHYLOGENETIC CONTEXTS R ic h a r d L. Z u s i1 Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History, P.O. -

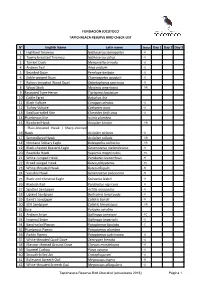

N° English Name Latin Name Status Day 1 Day 2

FUNDACIÓN JOCOTOCO TAPICHALACA RESERVE BIRD CHECK-LIST N° English Name Latin name Status Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 1 Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei - R 2 Tawny-breasted Tinamou Nothocercus julius - U 3 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata - U 4 Andean Teal Anas andium - U 5 Bearded Guan Penelope barbata - U 6 Sickle-winged Guan Chamaepetes goudotii - U 7 Rufous-breasted Wood Quail Odontophorus speciosus - R 8 Wood Stork Mycteria americana - VR 9 Fasciated Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma fasciatum 10 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 11 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus - U 12 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura - U 13 Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus - U 14 Plumbeous Kite Ictinia plumbea 15 Bicolored Hawk Accipiter bicolor - VR Plain-breasted Hawk / Sharp-shinned 16 Hawk Accipiter striatus - U 17 Semicollared Hawk Accipiter collaris - VR 18 Montane Solitary Eagle Buteogallus solitarius - VR 19 Black-chested Buzzard-Eagle Geranoaetus melanoleucus - R 20 Roadside Hawk Rupornis magnirostris - FC 21 White-rumped Hawk Parabuteo leucorrhous - R 22 Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus - FC 23 White-throated Hawk Buteo albigula - R 24 Variable Hawk Geranoaetus polyosoma - R 25 Black-and-chestnut Eagle Spizaetus isidori - R 26 Blackish Rail Pardirallus nigricans - R 27 Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius - R 28 Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda - R 29 Baird's Sandpiper Calidris bairdii - R 30 Stilt Sandpiper Calidris himantopus - VR 31 Sora Porzana carolina 32 Andean Snipe Gallinago jamesoni - FC 33 Imperial Snipe Gallinago imperialis - U 34 Band-tailed Pigeon Patagioenas