Acting with Other Factorsin a Variety Ofcontexts, Mating Frequency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papilio (New Series) #24 2016 Issn 2372-9449

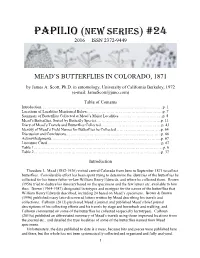

PAPILIO (NEW SERIES) #24 2016 ISSN 2372-9449 MEAD’S BUTTERFLIES IN COLORADO, 1871 by James A. Scott, Ph.D. in entomology, University of California Berkeley, 1972 (e-mail: [email protected]) Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………..……….……………….p. 1 Locations of Localities Mentioned Below…………………………………..……..……….p. 7 Summary of Butterflies Collected at Mead’s Major Localities………………….…..……..p. 8 Mead’s Butterflies, Sorted by Butterfly Species…………………………………………..p. 11 Diary of Mead’s Travels and Butterflies Collected……………………………….……….p. 43 Identity of Mead’s Field Names for Butterflies he Collected……………………….…….p. 64 Discussion and Conclusions………………………………………………….……………p. 66 Acknowledgments………………………………………………………….……………...p. 67 Literature Cited……………………………………………………………….………...….p. 67 Table 1………………………………………………………………………….………..….p. 6 Table 2……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 37 Introduction Theodore L. Mead (1852-1936) visited central Colorado from June to September 1871 to collect butterflies. Considerable effort has been spent trying to determine the identities of the butterflies he collected for his future father-in-law William Henry Edwards, and where he collected them. Brown (1956) tried to deduce his itinerary based on the specimens and the few letters etc. available to him then. Brown (1964-1987) designated lectotypes and neotypes for the names of the butterflies that William Henry Edwards described, including 24 based on Mead’s specimens. Brown & Brown (1996) published many later-discovered letters written by Mead describing his travels and collections. Calhoun (2013) purchased Mead’s journal and published Mead’s brief journal descriptions of his collecting efforts and his travels by stage and horseback and walking, and Calhoun commented on some of the butterflies he collected (especially lectotypes). Calhoun (2015a) published an abbreviated summary of Mead’s travels using those improved locations from the journal etc., and detailed the type localities of some of the butterflies named from Mead specimens. -

This Site Captures Roadside Habitat and Surrounding Second-Growth

Seldom Seen Corners CA This site captures roadside habitat and surrounding second-growth deciduous forest that supports populations of Indian skipper butterfly ( Hesperia sassacus ) and long dash butterfly ( Polites mystic ), invertebrate species of conservation concern in Pennsylvania. Butterflies undergo four stages in their life cycle: egg, caterpillar, pupa, and adult. Once an adult female has mated, she seeks out the species of host plant appropriate for her species on which to lay her fertilized eggs. Most species lay their eggs on a plant that the newly hatched caterpillar will eat. When an egg hatches, a small caterpillar emerges and spends all its time eating and growing. As a caterpillar grows, it sheds its exoskeleton – usually three or four times – over Indian skipper butterfly. Photo: Will Cook the course of two to three weeks. During the caterpillar stage, the animal is highly vulnerable to predation by wasps and birds, parasitization by wasps or flies, or infection by fungal or viral pathogens; most caterpillars do not survive to the next stage of development. Once a caterpillar has reached full size, it attaches itself to a support and encases itself in a hard outer shell (chrysalis), and becomes a pupa. While in the pupa stage, the butterfly transforms into an adult. When the adult inside the chrysalis is fully formed, the chrysalis splits and the adult butterfly emerges (Glassberg 1999). Habitat for Indian skipper is old fields, pastures, and clearings. The caterpillars live in silken tubes at the base of grass clumps and leave them to feed. The older caterpillars overwinter and in the spring pupate in a loose cocoon. -

An Annotated List of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 38: 1–549 (2010) Annotated list of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.38.383 MONOGRAPH www.pensoftonline.net/zookeys Launched to accelerate biodiversity research An annotated list of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada Gregory R. Pohl1, Gary G. Anweiler2, B. Christian Schmidt3, Norbert G. Kondla4 1 Editor-in-chief, co-author of introduction, and author of micromoths portions. Natural Resources Canada, Northern Forestry Centre, 5320 - 122 St., Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6H 3S5 2 Co-author of macromoths portions. University of Alberta, E.H. Strickland Entomological Museum, Department of Biological Sciences, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E3 3 Co-author of introduction and macromoths portions. Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, K.W. Neatby Bldg., 960 Carling Ave., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0C6 4 Author of butterfl ies portions. 242-6220 – 17 Ave. SE, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2A 0W6 Corresponding authors: Gregory R. Pohl ([email protected]), Gary G. Anweiler ([email protected]), B. Christian Schmidt ([email protected]), Norbert G. Kondla ([email protected]) Academic editor: Donald Lafontaine | Received 11 January 2010 | Accepted 7 February 2010 | Published 5 March 2010 Citation: Pohl GR, Anweiler GG, Schmidt BC, Kondla NG (2010) An annotated list of the Lepidoptera of Alberta, Canada. ZooKeys 38: 1–549. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.38.383 Abstract Th is checklist documents the 2367 Lepidoptera species reported to occur in the province of Alberta, Can- ada, based on examination of the major public insect collections in Alberta and the Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes. -

How to Use This Checklist

How To Use This Checklist Swallowtails: Family Papilionidae Special Note: Spring and Summer Azures have recently The information presented in this checklist reflects our __ Pipevine Swallowtail Battus philenor R; May - Sep. been recognized as separate species. Azure taxonomy has not current understanding of the butterflies found within __ Zebra Swallowtail Eurytides marcellus R; May - Aug. been completely sorted out by the experts. Cleveland Metroparks. (This list includes all species that have __ Black Swallowtail Papilio polyxenes C; May - Sep. __ Appalachian Azure Celastrina neglecta-major h; mid - late been recorded in Cuyahoga County, and a few additional __ Giant Swallowtail Papilio cresphontes h; rare in Cleveland May; not recorded in Cuy. Co. species that may occur here.) Record you observations and area; July - Aug. Brush-footed Butterflies: Family Nymphalidae contact a naturalist if you find something that may be of __ Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Papilio glaucus C; May - Oct.; __ American Snout Libytheana carinenta R; June - Oct. interest. females occur as yellow or dark morphs __ Variegated Fritillary Euptoieta claudia R; June - Oct. __ Spicebush Swallowtail Papilio troilus C; May - Oct. __ Great Spangled Fritillary Speyeria cybele C; May - Oct. Species are listed taxonomically, with a common name, a Whites and Sulphurs: Family Pieridae __ Aphrodite Fritillary Speyeria aphrodite O; June - Sep. scientific name, a note about its relative abundance and flight __ Checkered White Pontia protodice h; rare in Cleveland area; __ Regal Fritillary Speyeria idalia X; no recent Ohio records; period. Check off species that you identify within Cleveland May - Oct. formerly in Cleveland Metroparks Metroparks. __ West Virginia White Pieris virginiensis O; late Apr. -

Butterfly Checklist 2013 Date Or Location of Observation ABCD

Butterfly Checklist 2013 Date or Location of Observation ABCD Skippers (Hesperiidae) Silver-spotted Skipper (Epargyreus clarus) N, U Northern Cloudywing (Thorybes pylades) N, R Wild Indigo Duskywing (Erynnis baptisiae) N, C Dreamy Duskywing (Erynnis icelus) N, U Juvenal's Duskywing (Erynnis juvenalis) N, C Columbine Duskywing (Erynnis lucilius) N, U Mottled Duskywing (Erynnis martialis) N, R Common Sootywing (Pholisora catullus) N, U Arctic Skipper (Carterocephalus palaemon) N, U Least Skipper (Ancyloxypha numitor) N, C European Skipper (Thymelicus lineola) E Fiery Skipper (Hylephila phyleus) N, R Leonardus Skipper (Hesperia leonardus) N, R Indian Skipper (Hesperia sassacus) N, R Long Dash (Polites mystic) N,C Crossline Skipper (Polites origenes) N, C Peck's Skipper (Polites peckius) N, C Tawny-edged Skipper (Polites themistocles) N, C Northern Broken Dash (Wallengrenia egeremet) N,C Little Glassywing (Pompeius verna) N, C Mulberry Wing (Poanes massasoit) N, R Hobomok Skipper (Poanes hobomok) N, C Broad-winged Skipper (Poanes viator) N, C Delaware Skipper (Anatrytone logan) N, C Dion Skipper (Euphyes dion) N, U Black Dash (Euphyes conspicua) N, U Two-spotted Skipper (Euphyes bimacula) N,R Dun Skipper (Euphyes vestris) N, C Ocola Skipper (Panoquina ocola) N, R Swallowtails (Papilionidae) Giant Swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes) N, U Eastern Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio glaucus) N, C Black Swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes) N, C Spicebush Swallowtail (Papilio troilus) N, R Mourning Cloak, Chris Hamilton Eastern Tiger Swallowtail, Hamilton Conservation -

Butterflies Swan Island

Checkerspots & Crescents Inornate Ringlet ↓ Coenonympha tullia The Ringlet has a Harris’s Checkerspot Chlosyne harrisii bouncy, irregular Pearl Crescent ↓ Phyciodes tharos flight pattern. Abundant in open Crescents fly from fields from late May May to October. to early October. Especially common Common Wood Nymph ↓ Cercyonis pegala on dirt roads. Pearl and Northern hard The Common to differentiate. Wood Nymph is Northern Pearl Crescent Phyciodes cocyta very abundant. Flies from July to Eastern Comma Polygonia comma Sept. along wood Mourning Cloak Nymphalis antiopa edges and fields. Red Admiral Vanessa atalanta ______________________________________ Butterflies American Lady ↓ Vanessa virginiensis ______________________________________ of ______________________________________ American Lady found on dirt Swan Island roads and open Perkins TWP, Maine patches in fields. Steve Powell Wildlife Flight period is April to October. Management Area White Admiral Limenitis arthemis Viceroy Limenitis archippus ______________________________________ ______________________________________ Satyrs Great Spangled Fritillary Northern Pearly-Eye Enodia anthedon Eyed Brown ↓ Satyrodes eurydice Eyed Brown found in wet, wooded Swan Island – Explore with us! www.maine.gov/swanisland edges. Has erratic Maine Butterfly Survey flight pattern. Flies Checklist and brochure created by Robert E. mbs.umf.maine.edu from late June to Gobeil and Rose Marie F. Gobeil in cooperation with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries Photos of Maine Butterflies early August. www.mainebutterflies.com and Wildlife (MDIFW). Photos by Rose Marie F. Gobeil Little Wood Satyr Megisto cymela ______________________________________ SECOND PRINTING: APRIL 2019 Skippers Pepper & Salt Skipper Amblyscirtes hegon Banded Hairstreak ↓ Satyrium calanus Swallowtails Banded Hairstreak: Silver-spotted Skipper ↓Epargyreus clarus uncommon, found Silver-spotted Black Swallowtail Papilio polyxenes in open glades in Skipper is large Canadian Tiger Swallowtail ↓ Papilio canadensis wooded areas. -

Recovery Strategy for the Dakota Skipper (Hesperia Dacotae) in Canada

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Dakota Skipper (Hesperia dacotae) in Canada Dakota Skipper 2007 About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)? SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is “to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.” What is recovery? In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species’ persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured. What is a recovery strategy? A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage. Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies — Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada — under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARA (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/the_act/default_e.cfm) outline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series. -

Common Butterflies Niobrara Valley Preserve

Common Butterflies - of the - Niobrara Valley Preserve By Neil Dankert Layout and design by Jonathan Nikkila This field guide is the result of 33 years of butterfly research on the Niobrara Valley Preserve. It is hoped that this field guide will enhance the visitor experience at the Preserve and illustrate the great diversity of the Niobrara River area. All butterfly specimen photos are life size to aid with identifications. Five years after The Nature Conservancy’s purchase of the Preserve in 1980, Dr. Harold Nagel (professor Kearney State College) and Neil Dankert (B.S. Biology, Kearney State College) undertook a two year survey to document the occurence and population status of butterfly species found on the Preserve. After this survey, annual butterfly counts were begun (held on or around July 4th every year) which Mr. Dankert continued after Dr. Nagel’s retirement. 2018 marked the 31st year of counts. This research greatly enhanced knowledge of the butterfly fauna in the area. At the time of the Preserve’s purchase Brown County had 49 recorded butterfly species while Keya Paha had 53. Currently these totals are at 85 and 83 species. Special thanks to the staff, past and present, of the Niobrara Valley Preserve and the Nature Conservancy for considerations afforded us over the past 33 years and to the count participants – too numerous to mention – for their time, efforts and support. Butterflies of the Niobrara Valley Preserve 3 Table of Contents --- Page 4... Large Black/Yellow Butterflies Giant Swallowtail Page 6... Large Yellow/Black Butterflies Two Tailed and Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Page 8.. -

Alberta Lepidopterists' Guild Newsletter Spring 2017

ALBERTA LEPIDOPTERISTS’ GUILD NEWSLETTER SPRING 2017 Welcome to the ALG Newsletter, a compendium of news, reports, and items of interest related to lepidopterans and lepidopterists in Alberta. The newsletter is produced twice per year, in spring and fall, edited by John Acorn. Actias luna, Emily Gorda, June 5, 2017, Cold Lake, Alberta Contents: Pohl and Macaulay: Additions and Corrections to the Alberta Lep. List.........................................2 Macnaughton: The Prairie Province Butter>ly Atlas................................................................................5 Pang: Song for a Painted Lady..........................................................................................................................14 Romanyshyn: Quest for Euchloe creusa......................................................................................................15 Bird: Dry Island Butter>ly Count.....................................................................................................................16 Letters to ALG..........................................................................................................................................................19 Acorn: From the Editor, and Butter>ly Roundup Update.....................................................................23 ALG Newsletter Spring 2017– Page 1 Additions to the Alberta Lepidoptera List, and Corrections to the 2016 Update Greg Pohl and Doug Macaulay This note is both an update to the provincial checklist, and a corrigendum to the 2016 -

The Status of Dakota Skipper (Hesperia Dacotae Skinner) in Eastern South Dakota and the Effects of Land Management

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020 The Status of Dakota Skipper (Hesperia dacotae Skinner) in Eastern South Dakota and the Effects of Land Management Kendal Annette Davis South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Kendal Annette, "The Status of Dakota Skipper (Hesperia dacotae Skinner) in Eastern South Dakota and the Effects of Land Management" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3914. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/3914 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE STATUS OF DAKOTA SKIPPER (HESPERIA DACOTAE SKINNER) IN EASTERN SOUTH DAKOTA AND THE EFFECTS OF LAND MANAGEMENT BY KENDAL ANNETTE DAVIS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Major in Plant Sciences South Dakota State University 2020 ii THESIS ACCEPTANCE PAGE KENDAL ANNETTE DAVIS This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investigation by a candidate for the master’s degree and is acceptable for meeting the thesis requirements for this degree. Acceptance of this does not imply that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. Paul Johnson Advisor Date David Wright Department Head Date Dean, Graduate School Date iii AKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank my advisor, Dr. -

Long Dash — Wisconsinbutterflies.Org Page 1 of 5

Long Dash — wisconsinbutterflies.org Page 1 of 5 Wisconsin Butterflies z butterflies z tiger beetles z robber flies Search species Long Dash Polites mystic This butterfly is a fairly easy one to identify when it is fresh with very distinct markings on the hindwing below, but as it wears it becomes a very light skipper where the markings are barely visible. Thus, late in their flight period if I see a light, very worn skipper that doesn’t have easily seen markings it is often this species. In Florence County in 2007 I saw two very worn individuals that contrasted greatly with the very fresh Common Branded Skippers that I was trying to photograph. These individuals were nearly white underneath with barely visible lighter markings on the hind wing below. One of the things that I have noticed about photos that are usually seen online and especially in books is that they are of fresh, nice looking butterflies or skippers. I am sure that I have taken some photos of these worn specimens of this species but even I seemed to have trashed them. Although on the bottom photo you still can easily see the markings on the hind wing below, in more worn individuals these markings are nearly nonexistent. I hope to take a photo of a worn specimen to show this difference. Weekly sightings for Long Dash Identifying characteristics Below, the wings are various shades of brown with a very distinct lighter spot band on the hindwing. Above, the male is orange with a long, wide stigma and a dark border on the forewing. -

A Bibliography of the Catalogs, Lists, Faunal and Other Papers on The

A Bibliography of the Catalogs, Lists, Faunal and Other Papers on the Butterflies of North America North of Mexico Arranged by State and Province (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera) WILLIAM D. FIELD CYRIL F. DOS PASSOS and JOHN H. MASTERS SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 157 SERIAL PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION The emphasis upon publications as a means of diffusing knowledge was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. In his formal plan for the Insti- tution, Joseph Henry articulated a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This keynote of basic research has been adhered to over the years in the issuance of thousands of titles in serial publications under the Smithsonian imprint, com- mencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Annals of Flight Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes original articles and monographs dealing with the research and collections of its several museums and offices and of professional colleagues at other institutions of learning. These papers report newly acquired facts, synoptic interpretations of data, or original theory in specialized fields. These pub- lications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, laboratories, and other interested institutions and specialists throughout the world.