Enclosing the Pristine Myth: the Case of Madhav National Park, India 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tamarind 1990 - 2004

Tamarind 1990 - 2004 Author A. K. A. Dandjouma, C. Tchiegang, C. Kapseu and R. Ndjouenkeu Title Ricinodendron heudelotii (Bail.) Pierre ex Pax seeds treatments influence on the q Year 2004 Source title Rivista Italiana delle Sostanze Grasse Reference 81(5): 299-303 Abstract The effects of heating Ricinodendron heudelotii seeds on the quality of the oil extracted was studied. The seeds were preheated by dry and wet methods at three temperatures (50, 70 and 90 degrees C) for 10, 20, 30 and 60 minutes. The oil was extracted using the Soxhlet method with hexane. The results showed a significant change in oil acid value when heated at 90 degrees C for 60 minutes, with values of 2.76+or-0.18 for the dry method and 2.90+or-0.14 for the wet method. Heating at the same conditions yielded peroxide values of 10.70+or-0.03 for the dry method and 11.95+or-0.08 for the wet method. Author A. L. Khandare, U. Kumar P, R. G. Shanker, K. Venkaiah and N. Lakshmaiah Title Additional beneficial effect of tamarind ingestion over defluoridated water supply Year 2004 Source title Nutrition Reference 20(5): 433-436 Abstract Objective: We evaluated the effect of tamarind (Tamarindus indicus) on ingestion and whether it provides additional beneficial effects on mobilization of fluoride from the bone after children are provided defluoridated water. Methods: A randomized, diet control study was conducted in 30 subjects from a fluoride endemic area after significantly decreasing urinary fluoride excretion by supplying defluoridated water for 2 wk. -

Ancient Hindu Rock Monuments

ISSN: 2455-2631 © November 2020 IJSDR | Volume 5, Issue 11 ANCIENT HINDU ROCK MONUMENTS, CONFIGURATION AND ARCHITECTURAL FEATURES OF AHILYA DEVI FORT OF HOLKAR DYNASTY, MAHISMATI REGION, MAHESHWAR, NARMADA VALLEY, CENTRAL INDIA Dr. H.D. DIWAN*, APARAJITA SHARMA**, Dr. S.S. BHADAURIA***, Dr. PRAVEEN KADWE***, Dr. D. SANYAL****, Dr. JYOTSANA SHARMA***** *Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University Raipur C.G. India. **Gurukul Mahila Mahavidyalaya Raipur, Pt. R.S.U. Raipur C.G. ***Govt. NPG College of Science, Raipur C.G. ****Architectural Dept., NIT, Raipur C.G. *****Gov. J. Yoganandam Chhattisgarh College, Raipur C.G. Abstract: Holkar Dynasty was established by Malhar Rao on 29th July 1732. Holkar belonging to Maratha clan of Dhangar origin. The Maheshwar lies in the North bank of Narmada river valley and well known Ancient town of Mahismati region. It had been capital of Maratha State. The fort was built by Great Maratha Queen Rajmata Ahilya Devi Holkar and her named in 1767 AD. Rani Ahliya Devi was a prolific builder and patron of Hindu Temple, monuments, Palaces in Maheshwar and Indore and throughout the Indian territory pilgrimages. Ahliya Devi Holkar ruled on the Indore State of Malwa Region, and changed the capital to Maheshwar in Narmada river bank. The study indicates that the Narmada river flows from East to west in a straight course through / lineament zone. The Fort had been constructed on the right bank (North Wards) of River. Geologically, the region is occupied by Basaltic Deccan lava flow rocks of multiple layers, belonging to Cretaceous in age. The river Narmada flows between Northwards Vindhyan hillocks and southwards Satpura hills. -

Utilization of Lignocellulosic Waste from Bidi Industry for Removal of Dye from Aqueous Solution

Int. J. Environ. Res., 2(4): 385-390, Autumn 2008 ISSN: 1735-6865 Utilization of Lignocellulosic Waste from Bidi Industry for Removal of Dye from Aqueous Solution Nagda, G. K.* and Ghole, V. S. Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Pune, Pune, India Received 26 Oct 2007; Revised 15 March 2008; Accepted 15 April 2008 ABSTRACT: A new, local agro-industrial waste was valorized by chemical treatment and tested for its ability to remove cationic dye from aqueous solution. Tendu (Diospyros melanoxylon) leaves refuse, a solid waste from bidi industry which caused disposal problem, was studied as a biosorbent. Raw tendu waste (TLR), along with sulfuric acid carbonized tendu waste (TLR-CM) and tendu waste treated with dilute sulfuric acid (TLR-2N) were utilized as sorbent for uptake of crystal violet from aqueous solutions. Adsorption studies were carried out at various dye concentrations and contact times. It followed the pseudo-second-order kinetics and followed the Langmuir adsorption isotherm. Interestingly, milder acid treatment of the tendu waste enhanced biosorption, whereas drastic acid carbonization of tendu waste resulted in reduced adsorption of dye. The maximum adsorption capacities for crystal violet for TLR-2N, TLR and TLR-CM are 67.57, 42.92 and 22.47 mg/g respectively. Commercial activated carbon had maximum adsorption capacity for crystal violet of 151.52 mg/g. Thus a renewable solid waste with mild acid treatment can offer a cost effective alternative to activated carbon. Key words: Biosorption, Diospyros melanoxylon, Solid tendu waste, Dye, Crystal violet INTRODUCTION Colored wastewater is a consequence of synthetic textile dyes because of the chemical industrial processes both in the dye manufacturing stability of these pollutants (Anjaneyulu et al., industries and in the dye-consuming industries. -

REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932'

EAST INDIA (CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS) REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932' Presented by the Secretary of State for India to Parliament by Command of His Majesty July, 1932 LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H^M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2; 120, George Street, Edinburgh York Street, Manchester; i, St. Andrew’s Crescent, Cardiff 15, Donegall Square West, Belfast or through any Bookseller 1932 Price od. Net Cmd. 4103 A House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. The total cost of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) 4 is estimated to be a,bout £10,605. The cost of printing and publishing this Report is estimated by H.M. Stationery Ofdce at £310^ House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page,. Paras. of Members .. viii Xietter to Frim& Mmister 1-2 Chapter I.—^Introduction 3-7 1-13 Field of Enquiry .. ,. 3 1-2 States visited, or with whom discussions were held .. 3-4 3-4 Memoranda received from States.. .. .. .. 4 5-6 Method of work adopted by Conunittee .. .. 5 7-9 Official publications utilised .. .. .. .. 5. 10 Questions raised outside Terms of Reference .. .. 6 11 Division of subject-matter of Report .., ,.. .. ^7 12 Statistic^information 7 13 Chapter n.—^Historical. Survey 8-15 14-32 The d3masties of India .. .. .. .. .. 8-9 14-20 Decay of the Moghul Empire and rise of the Mahrattas. -

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens Distributed 1901 - 1990

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens distributed 1901 - 1990 Page 1 - https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/57407494 15 July 1901 Dr T Johnson FLS, Science and Art Museum, Dublin Two cases containing the following:- Ackd 20.7.01 1. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 2. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 3. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 4. Wood of Anogeissus acuminata, Ganjam, Paris Exhibition 1900 5. Wood of Xylia dolabriformis, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 6. Wood of Pterocarpus Marsupium, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 7. Wood of Lagerstremia parviflora, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 8. Wood of Anogeissus latifolia , Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 9. Wood of Gyrocarpus jacquini, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 10. Wood of Acrocarpus fraxinifolium, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 11. Wood of Ulmus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 12. Wood of Phyllanthus emblica, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 13. Wood of Adina cordifolia, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 14. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 15. Wood of Cedrela toona, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 16. Wood of Premna bengalensis, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 17. Wood of Artocarpus chaplasha, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 18. Wood of Artocarpus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 19. Wood of Ulmus wallichiana, N. India, Paris Exhibition 1900 20. Wood of Diospyros kurzii , India, Paris Exhibition 1900 21. Wood of Hardwickia binata, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 22. Flowers of Heterotheca inuloides, Mexico, Paris Exhibition 1900 23. Leaves of Datura Stramonium, Paris Exhibition 1900 24. Plant of Mentha viridis, Paris Exhibition 1900 25. Plant of Monsonia ovata, S. -

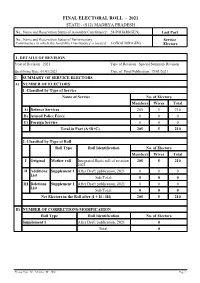

Final Electoral Roll

FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL - 2021 STATE - (S12) MADHYA PRADESH No., Name and Reservation Status of Assembly Constituency: 24-POHARI(GEN) Last Part No., Name and Reservation Status of Parliamentary Service Constituency in which the Assembly Constituency is located: 3-GWALIOR(GEN) Electors 1. DETAILS OF REVISION Year of Revision : 2021 Type of Revision : Special Summary Revision Qualifying Date :01/01/2021 Date of Final Publication: 15/01/2021 2. SUMMARY OF SERVICE ELECTORS A) NUMBER OF ELECTORS 1. Classified by Type of Service Name of Service No. of Electors Members Wives Total A) Defence Services 205 5 210 B) Armed Police Force 0 0 0 C) Foreign Service 0 0 0 Total in Part (A+B+C) 205 5 210 2. Classified by Type of Roll Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Members Wives Total I Original Mother roll Integrated Basic roll of revision 205 5 210 2021 II Additions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 0 0 0 List Sub Total: 0 0 0 III Deletions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 0 0 0 List Sub Total: 0 0 0 Net Electors in the Roll after (I + II - III) 205 5 210 B) NUMBER OF CORRECTIONS/MODIFICATION Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 0 Total: 0 Elector Type: M = Member, W = Wife Page 1 Final Electoral Roll, 2021 of Assembly Constituency 24-POHARI (GEN), (S12) MADHYA PRADESH A . Defence Services Sl.No Name of Elector Elector Rank Husband's Address of Record House Address Type Sl.No. Officer/Commanding Officer for despatch of Ballot Paper (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) Border Security Force 1 BHAGWAN SINGH M CT 145BN BSF, SALBAGAN, PO. -

Asian Ibas & Ramsar Sites Cover

■ INDIA RAMSAR CONVENTION CAME INTO FORCE 1982 RAMSAR DESIGNATION IS: NUMBER OF RAMSAR SITES DESIGNATED (at 31 August 2005) 19 Complete in 11 IBAs AREA OF RAMSAR SITES DESIGNATED (at 31 August 2005) 648,507 ha Partial in 5 IBAs ADMINISTRATIVE AUTHORITY FOR RAMSAR CONVENTION Special Secretary, Lacking in 159 IBAs Conservation Division, Ministry of Environment and Forests India is a large, biologically diverse and densely populated pressures on wetlands from human usage, India has had some country. The wetlands on the Indo-Gangetic plains in the north major success stories in wetland conservation; for example, of the country support huge numbers of breeding and wintering Nalabana Bird Sanctuary (Chilika Lake) (IBA 312) was listed waterbirds, including high proportions of the global populations on the Montreux Record in 1993 due to sedimentation problem, of the threatened Pallas’s Fish-eagle Haliaeetus leucoryphus, Sarus but following successful rehabilitation it was removed from the Crane Grus antigone and Indian Skimmer Rynchops albicollis. Record and received the Ramsar Wetland Conservation Award The Assam plains in north-east India retain many extensive in 2002. wetlands (and associated grasslands and forests) with large Nineteen Ramsar Sites have been designated in India, of which populations of many wetland-dependent bird species; this part 16 overlap with IBAs, and an additional 159 potential Ramsar of India is the global stronghold of the threatened Greater Sites have been identified in the country. Designated and potential Adjutant Leptoptilos dubius, and supports important populations Ramsar Sites are particularly concentrated in the following major of the threatened Spot-billed Pelican Pelecanus philippensis, Lesser wetland regions: in the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, two designated Adjutant Leptoptilos javanicus, White-winged Duck Cairina Ramsar Sites overlap with IBAs and there are six potential scutulata and wintering Baer’s Pochard Aythya baeri. -

National Parks in India (State Wise)

National Parks in India (State Wise) Andaman and Nicobar Islands Rani Jhansi Marine National Park Campbell Bay National Park Galathea National Park Middle Button Island National Park Mount Harriet National Park South Button Island National Park Mahatma Gandhi Marine National Park North Button Island National ParkSaddle Peak National Park Andhra Pradesh Papikonda National Park Sri Venkateswara National Park Arunachal Pradesh Mouling National Park Namdapha National Park Assam Dibru-Saikhowa National Park Orang National Park Manas National Park (UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Nameri National Park Kaziranga National Park (Famous for Indian Rhinoceros, UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Bihar Valmiki National Park Chhattisgarh Kanger Ghati National Park Guru Ghasidas (Sanjay) National Park Indravati National Park Goa Mollem National Park Gujarat Marine National Park, Gulf of Kutch Vansda National Park Blackbuck National Park, Velavadar Gir Forest National Park Haryana WWW.BANKINGSHORTCUTS.COM WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/BANKINGSHORTCUTS 1 National Parks in India (State Wise) Kalesar National Park Sultanpur National Park Himachal Pradesh Inderkilla National Park Khirganga National Park Simbalbara National Park Pin Valley National Park Great Himalayan National Park Jammu and Kashmir Salim Ali National Park Dachigam National Park Hemis National Park Kishtwar National Park Jharkhand Hazaribagh National Park Karnataka Rajiv Gandhi (Rameswaram) National Park Nagarhole National Park Kudremukh National Park Bannerghatta National Park (Bannerghatta Biological Park) -

Final Electoral Roll

FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL - 2021 STATE - (S12) MADHYA PRADESH No., Name and Reservation Status of Assembly Constituency: 16-GWALIOR Last Part EAST(GEN) No., Name and Reservation Status of Parliamentary Service Constituency in which the Assembly Constituency is located: 3-GWALIOR(GEN) Electors 1. DETAILS OF REVISION Year of Revision : 2021 Type of Revision : Special Summary Revision Qualifying Date :01/01/2021 Date of Final Publication: 15/01/2021 2. SUMMARY OF SERVICE ELECTORS A) NUMBER OF ELECTORS 1. Classified by Type of Service Name of Service No. of Electors Members Wives Total A) Defence Services 1202 74 1276 B) Armed Police Force 0 0 0 C) Foreign Service 2 1 3 Total in Part (A+B+C) 1204 75 1279 2. Classified by Type of Roll Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Members Wives Total I Original Mother roll Integrated Basic roll of revision 1200 75 1275 2021 II Additions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 11 0 11 List Sub Total: 11 0 11 III Deletions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 7 0 7 List Sub Total: 7 0 7 Net Electors in the Roll after (I + II - III) 1204 75 1279 B) NUMBER OF CORRECTIONS/MODIFICATION Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 0 Total: 0 Elector Type: M = Member, W = Wife Page 1 Final Electoral Roll, 2021 of Assembly Constituency 16-GWALIOR EAST (GEN), (S12) MADHYA PRADESH A . Defence Services Sl.No Name of Elector Elector Rank Husband's Address of Record House Address Type Sl.No. Officer/Commanding Officer for despatch of Ballot Paper (1) (2) (3) -

Asiatic Cheetah Relocation

Asiatic Cheetah relocation March 22, 2021 In news: By the end of the year 2021, nearly 70 years after the cheetah was declared locally extinct or extirpated, India will receive its first shipment of the cheetahs from Africa. Key Updates As part of the programme, two experts, one from Namibia and the other from South Africa the two countries with the highest cheetah populations in the world, will arrive to train Indian forest officers and wildlife experts on handling, breeding, rehabilitation, medical treatment and conservation of the animals. This is the first time in the world that a large carnivore will be relocated from one continent to another. Cheetah in India & India’s effort related to relocation of Cheetahs In India, this animal is believed to have disappeared from the country when Maharaja Ramanuj Pratap Singh Deo of Koriya hunted and shot the last three recorded Asiatic cheetahs in India in 1947. It was declared extinct by the government in 1952. The current relocation attempt began in 2009, it is only last year that the Supreme Court gave the green signal to the Centre. Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change had set up an expert committee under the chairmanship of Wildlife Trust of India board member and former Director Wildlife of the Indian Government, Dr M K Ranjitsinh, along with members of the Wildlife Institute of India, WWF, NTCA and officials from the Centre and states, have completed an assessment of the sites for relocation. As part of the programme, six sites, which had previously been assessed in 2010, have now been re- assessed by Wildlife Institute of India, Mukundara Hills Tiger Reserve and Shergarh Wildlife Sanctuary in Rajasthan and Gandhi Sagar Wildlife Sanctuary, Kuno National Park, Madhav National Park and Nauradehi Wildlife Sanctuary in Madhya Pradesh. -

GWALIOR & CHAMBAL DIVISION (Madhya Pradesh)- MONITORING

GWALIOR & CHAMBAL DIVISION (Madhya Pradesh)- MONITORING VISIT REPORT April-2013 1 INTRODUCTION A. Profile of the Gwalior & Chambal Division Gwalior and Chambal Divisions are administrative subdivisions of Madhya Pradesh consisting 9% & 6% of state population respectively. Gwalior Division covers five districts namely Ashoknagar, Datia, Guna, Gwalior, and Shivpuri and Chambal Division consists of the three districts namely Morena, Bhind and Sheopur. The MMR of the Chambal Division is 311 and Gwalior Division is 262. Four Districts in the Division have higher IMR & U5MR as compared to State average. The detailed analysis of HMIS data 2012-13 is attached in annexure-I Districts Population Blocks Villages Gwalior Division 6,646,375 24 4636 Gwalior 2,030,543 4 670 Datia 785,000 3 602 Guna 1,240,938 5 1259 Shivpuri 1,725,818 8 1273 Ashoknagar 864,076 4 832 Chambal Division 4,356,514 16 2363 Bhind 1,703,562 6 935 Morena 1,965,000 7 815 Sheopur 687,952 3 613 Grand Total 11,002,889 40 6999 Mortality Statistics –AHS 2011 IMR Neonatal MR U5MR MP 67 44 89 Bhind 53 29 66 Datia 75 43 99 Guna 79 48 96 Gwalior 51 35 69 Morena 64 36 87 Sheopur 74 42 101 Shivpuri 71 45 105 B. Visit Schedule District Facilities Gwalior Hatinapur PHC, Behat HSC, Dist. Hospital Murar Datia Sewada Civil Hospital Bhind Malanpur HSC, Dang HSC, Mehgaon CHC 2 OBSERVATIONS I. Public Health Infrastructure I. As per the population norm there is huge gap exist in terms of infrastructure (shortfall- 51% for SCs, 71%for PHCs and 55% for CHCs). -

Administrative Report on the Census of the Central India Agency, Madhya Pradesh

ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT ON THE CENSUS OF THE CENTRAL INDIA AGENCY, 1921 BY Lieut.-Colonel C. E. LUARD, C.I.E., M.A. (Oxon.), 1.A., Superintendent of Census Operations CALOUTTa SUl'ElUXTENDENT GOVERNMENT PRINTING, INDIA 19;?·~ Agents tor the Sale of Books Published by the Superintendent of Government Printing, India, Calcutta.. OJ EUROPE. COl1:stable & Cn., 10, Or .. n·~c StrJet, L)i'Jester Squa.re, Wneldon & Wesley. Ltd., 2, 3 & 4, Arthur Street, London, W.C. New Oxford Street, London, W. C. 2. Kegan Pa.nl, Tr'cndl, Trnbne" & Co., 68.;4, Carter L"ne, E.C., "au :J\I,New OKlord Street, London, Messrs. E~st and West Ltd.., 3, Victoria St., London, W.C S. W 1. BernMd Quaritch. 11. Gr",fton Stroot, New Bond n. H. Blackwell, GO & 51, Broad SLreet, OxfonJ:. Streot, London, W. Deighton Bell & Co., Ltd., Ca.mbridge. P. S. King & Sons, 2 & 4. Grea.t Smith Street Westminst~r, London, S.W. Oliver & Boyd, Tw"eddalo Ccmrt, Edinburgh. H. S. King & Co .• 65, Cornhill, E.C., and 9, Pal E. Ponsonby, Ltd., l!6, Grafton Stroot, Dublin. Mall, London, W. Ea.rnest Leroux, 28, Rue Bonap"rte, Pal'is. Grindla.v & Co., 54. Parliament Street, London, S.W. Lnzac & Co, 46, Grea.t Hussell Street, London, W.C· MarLinu. Nijhoil', Tho Hague, Holla.nd. W. Thacker & Co., 2, Crew La.no, London, E.C. Otto Harrassowitz" Leipzig. T. }<'isher Unwin, Ltd., No. I, Adelphi Terrace, Friedlander and Sohn, Berlin. London, W.C. IN INDIA AND CEYLON. Thacker, Splllk & Co., Calcutta and Simla.