Full Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John J. Marchi Papers

John J. Marchi Papers PM-1 Volume: 65 linear feet • Biographical Note • Chronology • Scope and Content • Series Descriptions • Box & Folder List Biographical Note John J. Marchi, the son of Louis and Alina Marchi, was born on May 20, 1921, in Staten Island, New York. He graduated from Manhattan College with first honors in 1942, later receiving a Juris Doctor from St. John’s University School of Law and Doctor of Judicial Science from Brooklyn Law School in 1953. He engaged in the general practice of law with offices on Staten Island and has lectured extensively to Italian jurists at the request of the State Department. Marchi served in the Coast Guard and Navy during World War II and was on combat duty in the Atlantic and Pacific theatres of war. Marchi also served as a Commander in the Active Reserve after the war, retiring from the service in 1982. John J. Marchi was first elected to the New York State Senate in the 1956 General Election. As a Senator, he quickly rose to influential Senate positions through the chairmanship of many standing and joint committees, including Chairman of the Senate Standing Committee on the City of New York. In 1966, he was elected as a Delegate to the Constitutional Convention and chaired the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Constitutional Issues. That same year, Senator Marchi was named Chairman of the New York State Joint Legislative Committee on Interstate Cooperation, the oldest joint legislative committee in the Legislature. Other senior state government leadership positions followed, and this focus on state government relations and the City of New York permeated Senator Marchi’s career for the next few decades. -

Robert F. Pecorella

1 The Two New Yorks Revisited: The City and The State Robert F. Pecorella On February 3, 1997, five members of the New York State Assembly from upstate districts introduced a concurrent resolution petitioning Congress to allow the division of New York into two states. The proponents defended the resolution in the following terms: “Due to the extreme diversity of New York State, it has become almost ungovernable. It is extremely difficult to write good law which is fair to all concerned when you have areas a diverse as Manhattan and Jefferson County, for instance.”1 This was certainly not the first proposal for geographical division of New York State, and it is unlikely that it will be the last. Regardless of whether the idea emanates from upstate or from New York City, it stands as a sym- bolic gesture of intense political frustration. People from New York City and people from other areas of the state and their political representatives often view each other with emotions ranging from bemusement to hostility. “Rural folk and city dwellers in many countries and over many centuries have viewed each other with fear and suspicion. [T]he sharp differences—racial, reli- gious, cultural, political—between New York City and upstate have aggra- vated the normal rural-urban cleavages.”2 As creations of modernity, cities challenge traditional culture by incubat- ing liberal social and political attitudes; as the nation’s most international city, New York represents the greatest challenge to the traditions of rural life. “From its earliest times . New York was a place of remarkable ethnic, cultural, and racial differences.”3 The differences between people in New York City and those in the rest of the state are both long-standing and easily summarized: city residents have been and are less Protestant, more ethnically diverse, more likely to be foreign-born, and far more likely to be Democrats than people in the rest of the state. -

August 12, 2004 Governor George Pataki Capitol Albany NY 12224

August 12, 2004 Governor George Pataki Capitol Albany NY 12224 Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno 909 Legislative Office Building Albany, New York 12247 Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver LOB 932 Albany, NY 12248 Re: Javits Center Expansion Legislation Dear Governor Pataki, Senator Bruno and Speaker Silver: For several years, Manhattan Community Board No. 4 has supported and continues to support the expansion of the Javits Convention Center. The Board and the communities of Chelsea and Clinton/Hell’s Kitchen believe that the expansion will create economic development and new jobs by better equipping the Javits Center to attract additional shows and exhibitions. However, it is entirely appropriate to ensure that this expansion, like other major development projects, undergoes a full and complete public review. A healthy respect for the local community and the democratic process demands no less. This project should be subject to the City’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP). This will enable our Board, residents, and businesses in the local community to comment on the project and allow the City Council and the City Planning Commission to vote on it. The elected legislative body of the City of New York should have a vote on such an important city asset. In particular, the closing of 39th Street should undergo the normal process for closing a city street. Major development projects within New York City should be reviewed and approved by the City’s elected officials. The fact that this is a State project on State-owned land is no excuse for shortcutting the local government’s process. -

Legislative Turnover Due to Ethical/Criminal Issues

CITIZENS UNION OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK TURNOVER IN THE NYS LEGISLATURE DUE TO ETHICAL OR CRIMINAL ISSUES, 1999 to 2015 May 4, 2015 Citizens Union in 2009 and 2011 released groundbreaking reports on turnover in the state legislature, finding that legislators are more likely to leave office due to ethical or criminal issues than to die in office, or be redistricted out of their seats.i Given corruption scandals continually breaking in Albany, Citizens Union provides on the following pages an updated list of all legislators who have left to date due to ethical or criminal misconduct. Since 2000, 28 state legislators have left office due to criminal or ethical issues and 5 more have been indicted, for a total of 33 legislators who have abused the public trust since 2000. Most recently in May 2015, Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos was charged with six federal counts of conspiracy, extortion, wire fraud and soliciting bribes, related to improper use of his public office in exchange for payments of $220,000 made to his son. His arrest comes less than five months after Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver’s indictment. The five legislators currently who have been charged with misconduct are: Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos, Senator Tom Libous, Senator John Sampson, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Assemblymember William Scarborough. In the 2013-2014 session alone, 8 legislators left office. Four legislators resigned in 2014: Assemblymembers Gabriela Rosa, William Boyland Jr., Dennis Gabryszak and Eric Stevenson. Two more left during the election season in 2014: Senator Malcolm Smith lost the Primary Election in 2014 and later was convicted of corruption, and Assemblymember Micah Kellner did not seeking re-election due to a sexual harassment scandal. -

Deregulating Corruption

Deregulating Corruption Ciara Torres-Spelliscy* The Roberts Supreme Court has, or to be more precise the five most conservative members of the Roberts Court have, spent the last twelve years branding and rebranding the meaning of the word “corruption” both in campaign finance cases and in certain white- collar criminal cases. Not only are the Roberts Court conservatives doing this over the strenuous objections of their more liberal colleagues, they are also breaking with the Rehn- quist Court’s more expansive definition of corruption. The actions of the Roberts Court in defining corruption to mean less and less have been a welcome development among dishon- est politicians. In criminal prosecutions, politicians convicted of honest services fraud and other crimes are all too eager to argue to courts that their convictions should be overturned in light of the Supreme Court’s lax definition of corruption. In some cases, jury convictions have been set aside for politicians who cite the Supreme Court’s latest campaign finance and white-collar crime cases, especially Citizens United v. FEC and McDonnell v. United States. This Article explores what the Supreme Court has done to rebrand corrup- tion, as well as how this impacts the criminal prosecutions of corrupt elected officials. This Article is the basis of a chapter of Professor Torres-Spelliscy’s second book, Political Brands, which will be published by Edward Elgar Publishing in late 2019. INTRODUCTION ................................................. 471 I. HOW AVERAGE VOTERS VIEW CORRUPTION . 474 II. HOW THE SUPREME COURT HAS CHANGED THE MEANING OF CORRUPTION IN CAMPAIGN FINANCE JURISPRUDENCE . 479 A. A Reasonable Take on Campaign Finance Reform from the Rehnquist Court ....................................... -

CPY Document

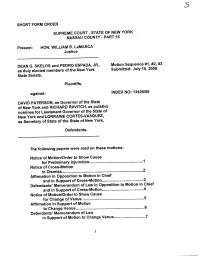

................... ........ .......... ... SHORT FORM ORDER SUPREME COURT - STATE OF NEW YORK NASSAU COUNTY - PART 15 Present: HON. WILLIAM R. LaMARCA Justice DEAN G. SKELOS and PEDRO ESPADA, JR., Motion Sequence #1, #2, #3 15, 2009 as duly elected members of the New York Submitted: July State Senate, Plaintiffs, -against- INDEX NO: 13426/09 DAVID PATERSON, as Governor of the State of New York and RICHARD RAVITCH, as putative nominee for Lieutenant Governor of the State of New York and LORRAINE CORTES-VASQUEZ, as Secretary of State of the State of New York, Defendants. The following papers were read on these motions: Notice of Motion/Order to Show Cause for Prelim inary Injunction.... Notice of Cross-Motion to Cis miss.......................................................................... Affrmation in Opposition to Motion in Chief and in Support of Cross-Motion............................. Defendants' Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Motion in Chief and in Support of Cross-Motion............................... Notice of Motion/Order to Show Cause for Change of Venue ........................................................ Affrmation in Support of Motion to Change V en ue......................... ........ .......... ....... Defendants' Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion to Change Venue......................... ............................................................................. ... Affirmations in Opposition to Cross-Motion and Motion to Change Venue.................................... Affidavit of Daniel Shapi ro.............. -

June 12, 2007 the Honorable Joseph Bruno New York State Senate 909

T HE C ITY OF N EW Y ORK O FFICE OF THE M AYOR N EW Y ORK, NY 10007 June 12, 2007 The Honorable Joseph Bruno New York State Senate 909 Legislative Office Building Albany, NY 12247 Dear Senator Bruno: I write to urge that you enact S5988 before the end of the legislative session, which will enable the City to reactivate a Marine Transfer Station (MTS) on the Gansevoort peninsula in Manhattan. Authorizing the reactivation of the Gansevoort MTS is the final legislative hurdle to implementing the historic Solid Waste Management Plan (SWMP) that was overwhelmingly adopted by the City Council last July and approved by the State DEC in October 2006. Implementation of the SWMP will eliminate an estimated 5.6 million truck miles traveled every year by both long-haul waste trucks in the City and Department of Sanitation (DSNY) trucks, and it will thereby reduce carbon emissions, significantly improve our air quality, and lead to a better quality of life for all New Yorkers. The SWMP will fundamentally transform how New York City handles its solid waste and recyclables, and will rectify the decades-long inequities that have forced a few communities to bear a substantially disproportionate share of sanitation facilities needed to handle the more than 22,000 tons of waste and recyclables that the City generates every day. The Gansevoort MTS is critical to ensuring that every borough, including Manhattan, is responsible for processing its own waste and recyclables rather than exporting them by truck to another borough. Failure to authorize the Gansevoort MTS will jeopardize the entire SWMP. -

Darren Dopp Sworn Testimony Transcript

1 1 STATE OF NEW YORK COMMISSION ON PUBLIC INTEGRITY 2 ================================== In the matter of 3 An Investigation into the Alleged 4 Misuse of Resources of the Division of State Police 5 ==================================== 6 Commission on Public Integrity 80 South Swan Street, Suite 1147 7 Albany, New York 12210-8004 8 Thursday, October 11, 2007 10:00 a.m. 9 STENOGRAPHIC RECORD of an Investigative 10 Interview under oath conducted pursuant to agreement. 11 12 INTERVIEWEE: DARREN DOPP 13 APPEARANCES: HERBERT TEITELBAUM, ESQ. 14 Executive Director 15 MEAVE M. TOOHER, ESQ. Investigative Counsel 16 JOAN P. SULLIVAN, ESQ. 17 Investigative Counsel 18 PRESENT: ROBERT SHEA, Investigator 19 TERENCE KINDLON, ESQ. 74 Chapel Street 20 Albany, New York 12207 (Appearing for the Interviewee) 21 22 23 REPORTED BY: BETH S. GOLDMAN, RPR 24 Certified Shorthand Reporter 2 1 D A R R E N D O P P, 2 called to testify before the Commission, and being 3 duly sworn/affirmed by the notary public, was 4 examined and testified as follows: 5 EXAMINATION BY MS. TOOHER: 6 Q. Would you state your full name for the 7 record, please. 8 A. My name is Darren Dopp. 9 Q. Mr. Dopp, where are you currently employed? 10 A. I am currently employed at a company called 11 Pat Lynch Communications here in Albany. 12 MR. TEITELBAUM: Let me interrupt you 13 for a second. 14 (A discussion was held off the record.) 15 Q. For the record, are you here voluntarily 16 today? 17 A. Yes. 18 Q. You are accompanied by your attorney? 19 A. -

$100 Million in Restore Ny Grants Announced for Community Development Projects

State of New York Executive Chamber Eliot Spitzer, Governor Press Office Stefanie Zakowicz (Upstate ESDC) - 716.856.8111 Warner Johnston (Downstate ESDC) - 212.803-3740 FOR RELEASE: IMMEDIATE 1/15/2008 $100 MILLION IN RESTORE NY GRANTS ANNOUNCED FOR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS Governor Eliot Spitzer, Lieutenant Governor David A. Paterson, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno today announced the recipients of $100 million in Restore New York grants. Empire State Development will provide funding to 64 projects statewide through its Restore NY Communities Initiative. Restore New York was designed to revitalize urban areas and stabilize neighborhoods as a means to attract residents and businesses. This announcement comes less than a week after Governor Spitzer delivered his State of the State address, where he spoke about the need to create livable communities. "The $100 million investment in Restore NY funding demonstrates the state’s commitment to provide a catalyst for meaningful community development projects throughout New York State," said Governor Spitzer as he traveled today in Utica, Plattsburgh and Ithaca. "This year’s projects represent the tremendous potential in urban communities, which will spur economic activity and allow our neighborhoods to flourish. Creating resonant communities will provide the foundation for New York’s Innovation Economy for generations to come." Lieutenant Governor David Paterson said: "This initiative provides critically needed resources in order to complete projects that can transform communities. Reviving community development, particularly in urban cores, can spur meaningful economic developments that create vibrant communities, where New Yorkers will want to live, work and raise families." Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver said: "The Restore NY program is a $300 million Assembly initiative based on a concept originated in Western New York, and I am pleased that the Governor is announcing this second round of important projects. -

Legislative Turnover Due to Ethical/Criminal Issues

CITIZENS UNION OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK TURNOVER IN THE NYS LEGISLATURE DUE TO ETHICAL OR CRIMINAL ISSUES, 1999 to 2015 January 22, 2015 Citizens Union in 2009 and 2011 released groundbreaking reports on turnover in the state legislature, finding that legislators are more likely to leave office due to ethical or criminal issues than to die in office, or be redistricted out of their seats.i Given corruption scandals continually breaking in Albany, Citizens Union provides on the following pages an updated list of all legislators who have left to date due to ethical or criminal misconduct. Since 2000, 28 state legislators have left office due to criminal or ethical issues and 4 more have been indicted, for a total of 32 legislators who have abused the public trust since 2000. Most recently in January in 2015, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver was charged with five federal counts of theft of honest services, wire fraud, mail fraud and extortion related to his receiving $4 million in referral fees due to improper use of his public position. The four legislators currently under indictment are: Senator Tom Libous, Senator John Sampson, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Assemblymember William Scarborough. In the 2013-2014 session alone, 8 legislators left office. Four legislators resigned in 2014: Assemblymembers Gabriela Rosa, William Boyland Jr., Dennis Gabryszak and Eric Stevenson. Two more left during the election season in 2014: Senator Malcolm Smith, after his indictment, lost the Primary Election in 2014, and Assemblymember Micah Kellner did not seeking re-election due to a sexual harassment scandal. -

Report of Investigation Into the Alleged Misuse of New York State Aircraft and the Resources of the New York State Police

REPORT OF INVESTIGATION INTO THE ALLEGED MISUSE OF NEW YORK STATE AIRCRAFT AND THE RESOURCES OF THE NEW YORK STATE POLICE STATE OF NEW YORK OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL July 23, 2007 This Report of Investigation into the Alleged Misuse of New York State Aircraft and the Resources of the New York State Police was prepared by: Ellen Nachtigall Biben Special Deputy Attorney General for Public Integrity Linda A. Lacewell Special Counsel Jerry H. Goldfeder Special Counsel TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................1 FINDINGS............................................................................................................2 PART ONE -- USE OF THE STATE POLICE TO COLLECT, CREATE, AND PRODUCE TO THE GOVERNOR’S LIAISON DOCUMENTS AND INFORMATION REGARDING SENATOR BRUNO’S TRAVEL ................4 I. BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW ....................................................................4 II. THE REPRESENTATION BY THE GOVERNOR’S OFFICE THAT IT WAS ACTING PURSUANT TO A FOIL REQUEST IS NOT SUPPORTED BY THE FACTS ......................................8 A. The Governor’s Office Had a Plan to Generate Press Coverage of Senator Bruno’s Use of State Aircraft ......................................8 B. The FOIL Requests .................................................................................9 III. EVEN ASSUMING THAT THE SUPERINTENDENT AND HOWARD WERE ACTING IN RESPONSE TO A FOIL REQUEST, THEIR CONDUCT WAS NOT REQUIRED UNDER FOIL AND DEVIATED FROM -

The New York State Legislative Process: an Evaluation and Blueprint for Reform

THE NEW YORK STATE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS: AN EVALUATION AND BLUEPRINT FOR REFORM JEREMY M. CREELAN & LAURA M. MOULTON BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE AT NYU SCHOOL OF LAW THE NEW YORK STATE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS: AN EVALUATION AND BLUEPRINT FOR REFORM JEREMY M. CREELAN & LAURA M. MOULTON BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE AT NYU SCHOOL OF LAW www.brennancenter.org Six years of experience have taught me that in every case the reason for the failures of good legislation in the public interest and the passage of ineffective and abortive legislation can be traced directly to the rules. New York State Senator George F. Thompson Thompson Asks Aid for Senate Reform New York Times, Dec. 23, 1918 Some day a legislative leadership with a sense of humor will push through both houses resolutions calling for the abolition of their own legislative bodies and the speedy execution of the members. If read in the usual mumbling tone by the clerk and voted on in the usual uninquiring manner, the resolution will be adopted unanimously. Warren Moscow Politics in the Empire State (Alfred A. Knopf 1948) The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law unites thinkers and advocates in pursuit of a vision of inclusive and effective democracy. Our mission is to develop and implement an innovative, nonpartisan agenda of scholarship, public education, and legal action that promotes equality and human dignity, while safeguarding fundamental freedoms. The Center operates in the areas of Democracy, Poverty, and Criminal Justice. Copyright 2004 by the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report represents the extensive work and dedication of many people.