The College All-Star Football Classic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerry Kramer

SCOUTING REPORT JERRY KRAMER Updated: March 19, 2016 Contents Overall Analysis __________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Game Reviews ____________________________________________________________________________________________ 5 REVISION LISTING DATE DESCRIPTION February 10, 2015 Initial Release March 19, 2016 Added the following games: 10/19/58, 11/15/59, and 1/15/67 OVERALL ANALYSIS Overall Analysis POSITION Right Guard HEIGHT AND WEIGHT Height: 6’3” Weight: 245 TEAMS 1958-68 Green Bay Packers UNIFORM NUMBER 64 SCOUTS Primary Scout: Ken Crippen Secondary Scout: Matt Reaser Page 1 http://www.kencrippen.com OVERALL ANALYSIS STRENGTHS • Excellent quickness and agility • Run blocking is exceptional • Can pull effectively and seal the blocks WEAKNESSES • Can get off-balance on pass blocking • Occasionally pushed back on a bull rush • Has a habit of not playing snap-to-whistle on pass plays BOTTOM LINE Kramer is excellent at run blocking, but not as good on pass blocking. Whether he is run blocking or pass blocking, he shows good hand placement. He missed many games in 1961 and 1964 due to injury. Also kicked field goals and extra points for the team in 1962-63 and 1968. He led the league in field goal percentage in 1962. Run Blocking: When pulling, he is quick to get into position and gains proper leverage against the defender. While staying on the line to run block, he shows excellent explosion into the defender and can turn the defender away from the runner. Pass Blocking: He can get pushed a little far into the backfield and lose his balance. He also has a habit of not playing snap-to-whistle. -

Tony Adamle: Doctor of Defense

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 24, No. 3 (2002) Tony Adamle: Doctor of Defense By Bob Carroll Paul Brown “always wanted his players to better themselves, and he wanted us known for being more than just football players,” Tony Adamle told an Akron Beacon Journal reporter in 1999. In the case of Adamle, the former Cleveland Browns linebacker who passed away on October 8, 2000, at age 76, his post-football career brought him even more honor than captaining a world championship team. Tony was born May 15, 1924, in Fairmont, West Virginia, to parents who had immigrated from Slovenia. By the time he reached high school, his family had moved to Cleveland where he attended Collinwood High. From there, he moved on to Ohio State University where he first played under Brown who became the OSU coach in 1941. World War II interrupted Adamle’s college days along with those of so many others. He joined the U.S. Air Force and served in the Middle East theatre. By the time he returned, Paul Bixler had succeeded Paul Brown, who had moved on to create Cleveland’s team in the new All-America Football Conference. Adamle lettered for the Buckeyes in 1946 and played well enough that he was selected to the 1947 College All-Star Game. He started at fullback on a team that pulled off a rare 16-0 victory over the NFL’s 1946 champions, the Chicago Bears. Six other members of the starting lineup were destined to make a mark in the AAFC, including the game’s stars, quarterback George Ratterman and running back Buddy Young. -

Mike Golic Named Walter Camp Man of the Year Recipient

For Immediate Release: November 9, 2018 Contact: Al Carbone (203) 671-4421 Follow us on Twitter @WalterCampFF Former Notre Dame Standout and Media Personality Mike Golic Named Walter Camp Man of the Year Recipient NEW HAVEN, CT – Former University of Notre Dame standout and current award-winning media personality Mike Golic is the recipient of the Walter Camp Football Foundation’s 2018 “Man of the Year” award. The Walter Camp “Man of the Year” award honors an individual who has been closely associated with the game of football as a player, coach or close attendant to the game. He must have attained a measure of success and been a leader in his chosen profession. He must have contributed to the public service for the benefit of his community, country and his fellow man. He must have an impeccable reputation for integrity and must be dedicated to our American Heritage and the philosophy of Walter Camp. Golic joins a distinguished list of former “Man of the Year” winners, including Roger Staubach (Navy), Gale Sayers (Kansas), Dick Butkus (Illinois), John Elway (Stanford), Jerome Bettis (Notre Dame), and last year’s recipient Calvin Johnson (Georgia Tech). “We are thrilled to have Mike Golic as our Man of the Year,” Foundation President Mike Madera said. “Not only has Mike had great success on the football field and in the broadcast booth, but he is a champion off the field as well. His work in the community is well-documented. We feel Mike is a great representation of what the Foundation stands for.” A native of Willowick, Ohio, Golic graduated from the University of Notre Dame in 1985 as a finance and management major. -

Illinois ... Football Guide

796.33263 lie LL991 f CENTRAL CIRCULATION '- BOOKSTACKS r '.- - »L:sL.^i;:f j:^:i:j r The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return to the library from which it was borrowed on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutllotlen, UNIVERSITY and undarllnlnfl of books are reasons OF for disciplinary action and may result In dismissal from ILUNOIS UBRARY the University. TO RENEW CAll TEUPHONE CENTEK, 333-8400 AT URBANA04AMPAIGN UNIVERSITY OF ILtlNOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN APPL LiFr: STU0i£3 JAN 1 9 \m^ , USRARy U. OF 1. URBANA-CHAMPAIGN CONTENTS 2 Division of Intercollegiate 85 University of Michigan Traditions Athletics Directory 86 Michigan State University 158 The Big Ten Conference 87 AU-Time Record vs. Opponents 159 The First Season The University of Illinois 88 Opponents Directory 160 Homecoming 4 The Uni\'ersity at a Glance 161 The Marching Illini 6 President and Chancellor 1990 in Reveiw 162 Chief llliniwek 7 Board of Trustees 90 1990 lUinois Stats 8 Academics 93 1990 Game-by-Game Starters Athletes Behind the Traditions 94 1990 Big Ten Stats 164 All-Time Letterwinners The Division of 97 1990 Season in Review 176 Retired Numbers intercollegiate Athletics 1 09 1 990 Football Award Winners 178 Illinois' All-Century Team 12 DIA History 1 80 College Football Hall of Fame 13 DIA Staff The Record Book 183 Illinois' Consensus All-Americans 18 Head Coach /Director of Athletics 112 Punt Return Records 184 All-Big Ten Players John Mackovic 112 Kickoff Return Records 186 The Silver Football Award 23 Assistant -

Baseball's All-Star Game

University of Central Florida STARS On Sport and Society Public History 6-27-1995 Baseball's All-Star Game Richard C. Crepeau University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Cultural History Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Sports Management Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Public History at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in On Sport and Society by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Crepeau, Richard C., "Baseball's All-Star Game" (1995). On Sport and Society. 392. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety/392 SPORT AND SOCIETY FOR H-ARETE June 27, 1995 Baseball's All-Star Game is coming up on Tuesday at The Ball Park in Arlington, one of the newest, and by most accounts one of the most beautiful of the new stadiums. Although the concept of an All-Star game dates back to 1858 and a game between all- star teams from Brooklyn and New York, it was sixty-two years ago that the first modern all-star game was held, July 6, 1933. In six decades this game has become a marvelous showcase for the best baseball talent, the marking point for mid-season, and a great promotional event for baseball. The game itself was the creation of Arch Ward sports editor of the Chicago Tribune who was able to persuade the owners to hold a game between the American and National League All-Stars in Chicago in conjunction with the Century of Progress Exhibition of 1933. -

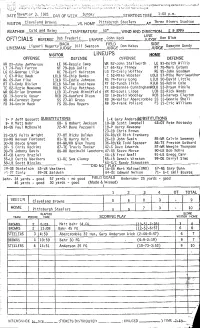

OFIICIALS Referelbob Frederic UMPIRE JUDGE BACK FIELD SIDE Ligourii4agert Swanson Don Hakes Duwaynegandy LINESMAN JIJDGE__

____ _____ _____ ______JUDGE___________ ' 'tSbi.Th,14i' 1(orn Al• (ireirt r, sm—un .J;'u Lv,e "Se s On ci Sunday 1:00 p.m. DAY OF WEEK TIME, Rivers Stadium VISITOR Cleveland Browns VS. HOMEPittsburgh Steelers AT__Three 500 WEATHER Cold and Rainy TEMPERATURE WIND AND DIRECTION. E @ 8MPH LI NE John Keck Ron Blum OFIICIALS REFERELBob Frederic UMPIRE JUDGE BACK FIELD SIDE LigouriI4agert Swanson Don Hakes DuwayneGandy LINESMAN JIJDGE__.. UN EU PS HOME OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE WR89—John Jefferson LE96—ReggieCamp WR82-John Stallworth LE93-Keith Willis LT74-Paul Farren NT79—Bob Golic LT65-Ray Pinney NT78—Mark Catano LG62-George Lilja RE78—Carl Hairston LG73-Craig Woifley RE95—John Goodman C61-Mike Baab LOLB56—Chip Banks C52-Mike Webster LOLB57-Mike Merriweather RG69—Dan Fike LJLB51—Eddie Johnson RG 74-Terry Long LILB50—David Little RT63—Cody Risien RILB50—Tom Cousineau PT62-Tunch 11km RILB56-RobinCole TE82-Ozzie Newsonie ROLB57—Clay Matthews TE89-Bennie CunninghamR0LB53-BryanHinkle t'JR86-Brian Brennan LCB31—Frank Hinnifield WR83-Louis Lipps LCB22-Rick Woods QB19—Bernie Kosar RC B29-Hanford Dixon QB19-David Woodley RCB33-Harvey Clayton RB44-Earnest Byner $527—Al Gross RB34-Walter Abercrombie SS31-Donnie Shell FB34-Kevin Mack ES20-Don Rogers RB3D-Frank Pollard FS21—Eric Williams 7— P Jeff GossettSUBSTITUTIONS 1-K Gary Anders&JJBSTITUTIONS 9- K Matt Bahr 68— G Robert Jackson 10-QB Scott Campbell 63-UT Pete Rostosky 16-05Paul McDonald 72-NT Dave Puzzuoli 16-P Harry Newsome 23—GB Chris Brown 22-GB/S FelixWright 77-01 Ricky Bolden 24-RB/KR -

Kapp-Ing a Memorable Campaign

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol 19, No. 1 (1997) Kapp-ing A Memorable Campaign `Injun' Joe Kapp spirited the '69 Vikings to an NFL championship By Ed Gruver He was called "Injun" Joe, despite the fact his heritage was a mix of Mexican and German blood, and he quarterbacked an NFL championship team, despite owning a passing arm that produced more wounded ducks than his hunter-head coach, Bud Grant, who spent pre-dawn hours squatting with a rifle in a Minneapolis duck blind. But in 1969, a season that remains memorable in the minds of Minnesota football fans, "Injun" Joe Kapp blazed a trail through the National Football League and bonded the Vikings into a formidable league champion, a family of men whose slogan, "Forty for Sixty," was testament to their togetherness. "I liked Joe," Grant said once. "Everybody liked Joe, he's a likeable guy. In this business, you play the people who get the job done, and Joe did that." John Beasley, who played tight end on the Vikings' '69 team, called Kapp "a piece of work...big and loud and fearless." Even the Viking defense rallied behind Kapp, an occurrence not so common on NFL teams, where offensive and defensive players are sometimes at odds with another. Witness the New York Giants teams of the late 1950s and early 1960s, where middle linebacker Sam Huff would tell halfback Frank Gifford, "Hold 'em Frank, and we'll score for you." No such situation occurred on the '69 Vikings, a fact made clear by Minnesota safety Dale Hackbart. "Playing with Kapp was like playing in the sandlot," Hackbart said. -

Illinois ... Football Guide

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign !~he Quad s the :enter of :ampus ife 3 . H«H» H 1 i % UI 6 U= tiii L L,._ L-'IA-OHAMPAIGK The 1990 Illinois Football Media Guide • The University of Illinois . • A 100-year Tradition, continued ~> The University at a Glance 118 Chronology 4 President Stanley Ikenberrv • The Athletes . 4 Chancellor Morton Weir 122 Consensus All-American/ 5 UI Board of Trustees All-Big Ten 6 Academics 124 Football Captains/ " Life on Campus Most Valuable Players • The Division of 125 All-Stars Intercollegiate Athletics 127 Academic All-Americans/ 10 A Brief History Academic All-Big Ten 11 Football Facilities 128 Hall of Fame Winners 12 John Mackovic 129 Silver Football Award 10 Assistant Coaches 130 Fighting Illini in the 20 D.I.A. Staff Heisman Voting • 1990 Outlook... 131 Bruce Capel Award 28 Alpha/Numerical Outlook 132 Illini in the NFL 30 1990 Outlook • Statistical Highlights 34 1990 Fighting Illini 134 V early Statistical Leaders • 1990 Opponents at a Glance 136 Individual Records-Offense 64 Opponent Previews 143 Individual Records-Defense All-Time Record vs. Opponents 41 NCAA Records 75 UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 78 UI Travel Plans/ 145 Freshman /Single-Play/ ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN Opponent Directory Regular Season UNIVERSITY OF responsible for its charging this material is • A Look back at the 1989 Season Team Records The person on or before theidue date. 146 Ail-Time Marks renewal or return to the library Sll 1989 Illinois Stats for is $125.00, $300.00 14, Top Performances minimum fee for a lost item 82 1989 Big Ten Stats The 149 Television Appearances journals. -

1967 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER the Following Players Comprise the 1967 Season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set

1967 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER The following players comprise the 1967 season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. ATLANTA ATLANTA BALTIMORE BALTIMORE OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Tommy McDonald End: Sam Williams EB: Willie Richardson End: Ordell Braase Jerry Simmons TC OC Jim Norton Raymond Berry Roy Hilton Gary Barnes Bo Wood OC Ray Perkins Lou Michaels KA KOA PB Ron Smith TA TB OA Bobby Richards Jimmy Orr Bubba Smith Tackle: Errol Linden OC Bob Hughes Alex Hawkins Andy Stynchula Don Talbert OC Tackle: Karl Rubke Don Alley Tackle: Fred Miller Guard: Jim Simon Chuck Sieminski Tackle: Sam Ball Billy Ray Smith Lou Kirouac -

Football Bowl Subdivision Records

FOOTBALL BOWL SUBDIVISION RECORDS Individual Records 2 Team Records 24 All-Time Individual Leaders on Offense 35 All-Time Individual Leaders on Defense 63 All-Time Individual Leaders on Special Teams 75 All-Time Team Season Leaders 86 Annual Team Champions 91 Toughest-Schedule Annual Leaders 98 Annual Most-Improved Teams 100 All-Time Won-Loss Records 103 Winningest Teams by Decade 106 National Poll Rankings 111 College Football Playoff 164 Bowl Coalition, Alliance and Bowl Championship Series History 166 Streaks and Rivalries 182 Major-College Statistics Trends 186 FBS Membership Since 1978 195 College Football Rules Changes 196 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Under a three-division reorganization plan adopted by the special NCAA NCAA DEFENSIVE FOOTBALL STATISTICS COMPILATION Convention of August 1973, teams classified major-college in football on August 1, 1973, were placed in Division I. College-division teams were divided POLICIES into Division II and Division III. At the NCAA Convention of January 1978, All individual defensive statistics reported to the NCAA must be compiled by Division I was divided into Division I-A and Division I-AA for football only (In the press box statistics crew during the game. Defensive numbers compiled 2006, I-A was renamed Football Bowl Subdivision, and I-AA was renamed by the coaching staff or other university/college personnel using game film will Football Championship Subdivision.). not be considered “official” NCAA statistics. Before 2002, postseason games were not included in NCAA final football This policy does not preclude a conference or institution from making after- statistics or records. Beginning with the 2002 season, all postseason games the-game changes to press box numbers. -

1976-04-13 V10 119.Pdf

Bleier appears before enthusiastic crowd, reflects on career by Cathy Nolan came to N.D. in 1964, Ara had just Staff Reporter come in, too, and brought football back to Notre Dame. Speaking before an enthusiastic "Before every game, I used to crowd at Washington Hall last say a prayer at the Grotto," Bleier Rocky Bleier, Senior Class said. "I asked for two things: , stressed the importance of either let me be All-American, or a ~--~n~~~:·setting attainable goals" and team captain." Bleier was chosen 'putting things in the right priori team captain. He contributed his ty ... responsibilities as captain as "hav Bleier, presently a fullback for ing helped hirn to look at his life'· the Pittsburgh Steelers, reflected and "put him in the right direc- on his four years at Notre Dame, tion.'' his football career, and his tour of --· ... unrversrty of notre dome st mary's college duty in Vietnam. Bleier said it was Vol. X, No. 119 Tuesday, a "privilege to come back as a Senior Class Fellow, but I didn't know if he really deserved the Tryouts may be reheld recognition.'' Commenting on coeducation at Notre Dame, Bleier said, "Notre Dame hasn't really changed for me. The only difference I noticed is New cheerleaders disputeU that now when I speak, I must say hello ladies and gentlemen, instead by Jim Commyn of just hello. gentlemen." Staff Reporter Bleier recalled an earlier visit he made to Notre Dame in 1969. "I The Notre Dame cheerleaders was on leave from the service, so I arc currently under tire because of decided to come back for the the proccchircs used in selecting NO-USC game. -

Jackie Smith: Revolutionary Receiver

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 16, No. 6 (1994) JACKIE SMITH: REVOLUTIONARY RECEIVER By Don Smith Jackie Smith wanted to play high school football but managed to see action for only half a season. He had no intention of playing college football but wound up as a four-year regular. He never even dreamed of playing professional football but he played 16 quality seasons in the National Football League. The improbable career of the 6-4, 232-pound tight end completed its incredible cycle in January, 1994, when he was accorded his sport's ultimate honor, election into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In between his aborted attempt to play football in high school and his final NFL season in 1978, Smith, hard- working and determined, fashioned a landmark career with the St. Louis Cardinals for 15 seasons from 1963 to 1977. He finished his pro football tenure with the Dallas Cowboys in 1978. At the time of his retirement, Smith ranked as the leading tight end receiver in NFL history. He had 480 catches for 7,918 yards and 40 touchdowns. Jackie hit his personal high-water mark with 56 receptions for 1,205 yards and nine touchdowns in 1967, when he was named to the all-NFL team. He caught more than 40 passes seven different years and was selected to play in the Pro Bowl after five of those seasons. Not only was he the top-ranking tight end when he retired, he also ranked llth among all career receivers and third among active receivers at the time.