How Chester Gould Created Characters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2014 Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College Recommended Citation Hernandez, Dahnya Nicole, "Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960" (2014). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 60. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/60 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUNNY PAGES COMIC STRIPS AND THE AMERICAN FAMILY, 1930-1960 BY DAHNYA HERNANDEZ-ROACH SUBMITTED TO PITZER COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE FIRST READER: PROFESSOR BILL ANTHES SECOND READER: PROFESSOR MATTHEW DELMONT APRIL 25, 2014 0 Table of Contents Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................................................2 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................3 Chapter One: Blondie.....................................................................................................................................18 Chapter Two: Little Orphan Annie............................................................................................................35 -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

October 2020

2020 Newsletter ACCLAIM HEALTH – ACTIVITY NEWSLETTER FAMOUS OCTOBER BIRTHDAYS October 1st, 1924 – Jimmy Carter was the 39th President of the United States of America, turns 95 this year! October 18th, 1919 – Pierre Trudeau was the former Prime Minister of Canada from 1980 – 1984. October 25th 1881 – Pablo Picasso was the world famous Spanish painter. He finished his first painting, The Picador at just 9 years old! ? October, 10th month October 29th 1959 – Mike Gartner, Famous Ice of the Gregorian calendar. Its name is hockey player turns 60! derived from octo, Latin for “eight,” an indication of its position in the early Roman calendar., Happy Birthday to our club membersAugustus, in celebrating their birthday’s in October 8BC,!! naming it after himself. Special dates in October Flower of the October 4th – World Smile Day month October 10th – National Cheese Day th The Flower for the October 15 – National I Love Lucy Day month is the October 28th – National Chocolate Marigold. It blooms Day in a variety of colours like red, yellow, white and orange. It stands for Creativity and symbolizes Peace and Tranquility. The Zodiac signs for October are: Libra (September 22 – October 22) Scorpio (October 23 – November 21 Movie Releases The Sisters was released on October 14th, 1938. Three daughters of a small-town pharmacist undergo trials and tribulations in their problematic marriages between 1904 and 1908. This film starred Bette Davis, Errol Flynn and Anita Louise. Have you seen it?! Songs of the month! (Click on the link below the song to listen) 1. Autumn in New York by Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong https://www.youtube.com/w atch?v=50zL8TnMBN8&featu Remember Charlie re=youtu.be Brown? “It’s the Great Pumpkin 2. -

Complete Chester Goulds Dick Tracy Volume 22 by Chester Gould Ebook

Complete Chester Goulds Dick Tracy Volume 22 by Chester Gould ebook Ebook Complete Chester Goulds Dick Tracy Volume 22 currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Complete Chester Goulds Dick Tracy Volume 22 please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Series:::: Dick Tracy (Book 22)+++Hardcover:::: 288 pages+++Publisher:::: Library of American Comics (June 27, 2017)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 9781631409011+++ISBN-13:::: 978-1631409011+++ASIN:::: 1631409018+++Product Dimensions::::8.8 x 1.1 x 11.4 inches++++++ ISBN10 9781631409011 ISBN13 978-1631409 Download here >> Description: Two worlds are in turmoil when the inter-species romance between Junior and Moon Maid heats up. Can the twinkling of little antennae be too far in the future? Back on Earth, Diet Smith introduces the Two-Way Wrist Television fifty years before the Apple Watch, while Moon Maid turns vigilante and a series of events reveal a mob plot to kill both her and Dick Tracy. The clues eventually lead to Mr. Bribery, who proudly displays his collection of shrunken heads of the people who have crossed him. Volume 22 includes the complete comic strips from April 13, 1964 through December 26, 1965. After hearing so many people complain about the moon era in Dick Tracy, I almost didnt get volume 21, and this volume; #22. I am glad that I got this book and judged for myself. I think the Moon maid is a brilliant and enchanting addition to Dick Tracy. I just dont really get all the complaints; I mean crime and action is really never very far away, and often interlaced with the Moon Maid story, with the Moon Maid herself having many crime-fighting tricks up her sleeves. -

Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop the DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY

$39.99 “The period covered in this volume is arguably one of the strongest in the Gould/Tracy canon, (Different in Canada) and undeniably the cartoonist’s best work since 1952's Crewy Lou continuity. “One of the best things to happen to the Brutality by both the good and bad guys is as strong and disturbing as ever…” comic market in the last few years was IDW’s decision to publish The Complete from the Introduction by Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy.” MAX ALLAN COLLINS —Scoop THE DICK COMPLETE DICK ® TRACY TRACY NEARLY 550 SEQUENTIAL COMICS OCTOBER 1954 In Volume Sixteen—reprinting strips from October 25, 1954 THROUGH through May 13, 1956—Chester Gould presents an amazing MAY 1956 Chester Gould (1900–1985) was born in Pawnee, Oklahoma. number of memorable characters: grotesques such as the He attended Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State murderous Rughead and a 467-lb. killer named Oodles, University) before transferring to Northwestern University in health faddist George Ozone and his wild boys named Neki Chicago, from which he was graduated in 1923. He produced and Hokey, the despicable "Nothing" Yonson, and the amoral the minor comic strips Fillum Fables and The Radio Catts teenager Joe Period. He then introduces nightclub photog- before striking it big with Dick Tracy in 1931. Originally titled Plainclothes Tracy, the rechristened strip became one of turned policewoman Lizz, at a time when women on the the most successful and lauded comic strips of all time, as well force were still a rarity. Plus for the first time Gould brings as a media and merchandising sensation. -

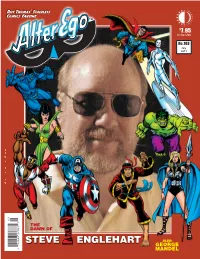

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

THE PALMS at SAN LAUREN by Blue Mountain 5300 Hageman Road • Bakersfield, CA 93308 • (661) 218-8330

THE PALMS AT SAN LAUREN by Blue Mountain 5300 Hageman Road • Bakersfield, CA 93308 • (661) 218-8330 September 2020 Message From Administrator MANAGEMENT TEAM Douglas G. Rice Executive Director Emily Conrad Resident Care Coordinator Ericka Aguirre Memory Care Coordinator Alysia Beene Marketing Director Ann Hauser Marketing Director Theresa Hernandez Dining Service Director Emmalin Cisneros Activity Director (AL) Sonia Ortega Medical Records Timoteo Soe Maintenance Director LICENSE #157208915 OFFICE HOURS MON-FRI 7:30 a.m.-5:00 p.m. Staying positive and helping one another out is key SAT-SUN 8:30 a.m.-5:00 p.m. to running a successful life. I often say to my staff, “I After Hours Assistance: Please call want you to come in and do better than you did 661-477-1241. A staff member can assist you. yesterday.” I firmly believe that setting personal goals and meeting them makes you successful personally and professionally. The Palms at San Lauren’s hope is that you keep you, and your families, happy and healthy. We are working hard to keep your loved ones safe. My staff and I will continue to educate ourselves so that we may provide the best care for our residents. Our community at The Palms is always striving to be better than we were the day before. VETERAN SOCIAL LIVE ENTERTAINMENT VIA ZOOM Employee On a hot July morning, our Veterans at The Palms at San Lauren were greeted with the Spotlight beautiful sound of the National Anthem played by Bakersfield’s own Mike Raney. As the trumpet played there was a feeling of pride and honor that swept over the small crowd. -

The Inventory of the Harold Gray Collection #100

The Inventory of the Harold Gray Collection #100 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Gray, Harold #100 Gifts of Mrs. Harold Gray and others, 1966-1992 Box 1 Folder 1 I. Correspondence. A. Reader mail. 1. Fan mail re: “Little Orphan Annie.” a. 1937. b. 1938. c. 1939. d. Undated (1930s). Folder 2 e. 1940-1943. Folder 3 f. 1944. Folder 4 g. 1945. Folder 5 h. 1946. Folder 6 i. 1947. Folder 7 j. 1948. Folder 8 k. 1949. 2 Box 1 cont’d. Folder 9 l. Undated (1940s). Folder 10 m. 1950. Folder 11 n. 1951. Folder 12 o. 1952. Folder 13 p. 1953-1955. Folder 14 q. 1957-1959. Folder 15 r. Undated (1950s). Folder 16 s. 1960. Folder 17 t. 1961. Folder 18 u. 1962. Folder 19 v. 1963. 3 Box 1 cont’d. Folder 20 w. 1964. Folder 21 x. 1965. Folder 22 y. 1966. Folder 23 z. 1967. Folder 24 aa. 1968. Folder 25 bb. Undated (1960s). Folder 26 2. Reader comments, criticisms and complaints. a. TLS re: depiction of social work in “Annie,” Mar. 3, 1937. Folder 27 b. Letters re: “Annie” character names, 1938-1966. Folder 28 c. Re: “Annie”’s dress and appearance, 1941-1952. Folder 29 d. Protests re: African-American character in “Annie,” 1942; includes: (i) “Maw Green” comic strip. 4 Box 1 cont’d. (ii) TL from HG to R. B. Chandler, publisher of the Mobile Press Register, explaining his choice to draw a black character, asking for understanding, and stating his personal stance on issue of the “color barrier,” Aug. -

Walt & Skeezix

Walt & Skeezix. by Frank O. King. 1921 & 1922. Drawn & Quarterly Books, MONTREAL. Introduction by Jeet Heer. with Chicago Research Notes by Tim Samuelson. A father and son take a walk through the woods in the fall. The father, Walt Wallet, 1960s, until now Frank King hasn’t received the ample appreciation often bestowed on is puffy and rumpled while his adopted son Skeezix is slight, with a young boy’s litheness. Herriman and Schulz by fans of good cartooning. The reason for this neglect is readily Alive with curiosity, Skeezix asks “Uncle Walt” why the fall leaves change color. The apparent: as a strip that dwelt on the daily travails of ordinary people, Gasoline Alley needs answers that Walt provides are less important than the tone and texture of the scene, a to be read in bulk to be appreciated. leisurely communion between parent and child that asks to be savored. Yet even in the pleasures of the moment, there is an undercurrent of sadness as well. The falling leaves The rhythm of Gasoline Alley is not the yuk-yuk gag a day humour of Dilbert nor the remind us that change is a constant part of experience and one day the son will have a life nail-biting melodrama of Dick Tracy. Rather, Gasoline Alley achieves its hold on the audience apart from the father. by being ruminative and cumulative: to catch the mood of the strip you have to imagine This bittersweet moment appeared in Frank King’s Gasoline Alley in a full-page Sunday yourself as the new kid on the block, slowly getting to know the familiar neighborhood strip late in 1930. -

Li'l Abner in Washington Today by Irv Sternberg a New York Mayor Read

Imagine: Li’l Abner in Washington Today By Irv Sternberg A New York mayor read them to children on the radio every Sunday morning. Some mimicked real people. They offered a daily respite from the dark days of the Depression, and were part of my life in the thirties and forties. My favorite comic strips as a child growing up in that period were ‘Li’l Abner,’ ‘Prince Valiant,’ ‘Dick Tracy,’ ‘Blondie,’ and ‘Rex Morgan, MD.’ Some can still be read in certain newspapers, a testimonial to their popularity over the decades. I’ve always favored cartoons that featured quirky characters in uncluttered drawings and told funny or exciting stories in a crisp style. I was amused by Li’l Abner and his friends in hillbilly country, by the well-told adventures and beautifully drawn panels of ‘Prince Valiant’ in the days of King Arthur, and by tough, square- jawed Dick Tracy who introduced the two-way radio wristwatch and the police procedural genre to the comic strips. Now, in the winter of my life, I still read the comics. My current favorites are ‘Pickles,’ ‘Zits,’ ‘Pluggers,’ ‘Luann,’ and ‘Beetle Bailey.’ I like ‘Pickles’ and ‘Pluggers’ because the writers seem to be eavesdropping on my life. In ‘Pickles,’ I relate to his characters, Earl and Opal. I recognize the oddball situations and sometimes testy conversation between these two old-timers. ‘Pluggers’ seems to be based on hilarious situations too close for comfort. ‘Zits’ is about a self-centered, self-indulgent teenager whose behavior is so outrageous I’m just grateful he’s not mine. -

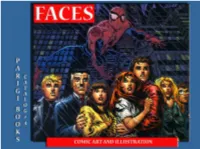

Faces Illustration Featuring, in No 1

face Parigi Books is proud to present fās/ a selection of carefully chosen noun original comic art and noun: face; plural noun: faces illustration featuring, in no 1. particular order, the front part of a person's Virgil Finlay, John Romita, John Romita, Jr, Romano Scarpa, head from the forehead to the Milo Manara, Magnus, Simone chin, or the corresponding part in Bianchi, Johnny Hart, Brant an animal. Parker, Don Rosa, Jeff MacNelly, Russell Crofoot, and many others. All items subject to prior sale. Enjoy! Parigi Books www.parigibooks.com [email protected] +1.518.391.8027 29793 Bianchi, Simone Wolverine #313 Double-Page Splash (pages 14 and 15) Original Comic Art. Marvel Comics, 2012. A spectacular double-page splash from Wolverine #313 (pages 14 and 15). Ink and acrylics on Bristol board. Features Wolverine, Sabretooth, and Romulus. Measures 22 x 17". Signed by Simone Bianchi on the bottom left corner. $2,750.00 30088 Immonen, Stuart; Smith, Cam Fantastic Four Annual #1 Page 31 Original Comic Art. Marvel Comics, 1998. Original comic art for Fantastic Four Annual #1, 1998. Measures approximately 28.5 x 44 cm (11.25 x 17.25"). Pencil and ink on art board. Signed by Stuart Immonen on the upper edge. A dazzling fight scene featuring a nice large shot of Crystal, of the Inhumans, the Wakandan princess Zawadi, Johnny Storm, Blastaar, and the Hooded Haunt. Condition is fine. $275.00 29474 Crofoot, Russel Original Cover Art for Sax Rohmer's Tales of Secret Egypt. No date. Original dustjacket art for the 1st US edition of Tales of Secret Egypt by Sax Rohmer, published by Robert McBride in 1919, and later reprinted by A. -

Commies, H-Bombs and the National Security State: the Cold War in The

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® History Faculty Publications History 1997 Commies, H-Bombs and the National Security State: The oldC War in the Comics Anthony Harkins Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/history_fac_pubs Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Anthony Harkins, “Commies, H-Bombs and the National Security State: The oC ld War in the Comics” in Gail W. Pieper and Kenneth D. Nordin, eds., Understanding the Funnies: Critical Interpretations of Comic Strips (Lisle, IL: Procopian Press, 1997): 12-36. This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harkins 13 , In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the U.S. government into the key components of what later historians would dub the "national securi ty state." The National Security Act of 1947 established a of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the National Security Council. The secret "NSC-68" document of 1950 advocated the development of hydrogen bomb, the rapid buildup of conventional forces, a worldwide sys tem of alliances with anti-Communist governments, and the unpn~ce'Clent€~CI mobilization of American society. That document became a blueprint for waging the cold war over the next twenty years. These years also saw the pas sage of the McCarran Internal Security Act (requiring all Communist organizations and their members to register with the government) and the n the era of Ronald Reagan and Newt Gingrich, some look back upon the rise of Senator Joseph McCarthy and his virulent but unsubstantiated charges 1950s as "a age of innocence and simplicity" (Miller and Nowak of Communists in the federal government.