Assessment of Grassland Ecosystem Conditions in the Southwestern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Para Especies Exóticas En México Eragrostis Curvula (Schrad.) Nees, 1841., CONABIO, 2016 1

Método de Evaluación Rápida de Invasividad (MERI) para especies exóticas en México Eragrostis curvula (Schrad.) Nees, 1841., CONABIO, 2016 Eragrostis curvula (Schrad.) Nees, 1841 Fuente: Tropical Forages E. curvula , es un pasto de origen africano, que se cultiva como ornamental y para detener la erosión; se establece en las orillas de carreteras y ambientes naturales como las dunas. Se ha utilizado contra la erosión, para la producción de forraje en suelos de baja fertilidad y para resiembra en pastizales semiáriados. Presenta abundante producción de semillas, gran capacidad para producir grandes cantidades de materia orgánica tanto en las raíces como en el follaje (Vibrans, 2009). Es capaz de desplazar a la vegetación natural. Favorece la presencia de incendios (Queensland Government, 2016). Información taxonómica Reino: Plantae Phylum: Magnoliophyta Clase: Liliopsida Orden: Poales Familia: Poaceae Género: Eragrostis Nombre científico: Eragrostis curvula (Schrad.) Nees, 1841 Nombre común: Zacate amor seco llorón, zacate llorón, zacate garrapata, amor seco curvado Resultado: 0.5109375 Categoría de invasividad: Muy alto 1 Método de Evaluación Rápida de Invasividad (MERI) para especies exóticas en México Eragrostis curvula (Schrad.) Nees, 1841., CONABIO, 2016 Descripción de la especie Hierba perenne, amacollada, de hasta 1.5 m de alto. Tallo a veces ramificado y con raíces en los nudos inferiores, frecuentemente con anillos glandulares. Hojas alternas, dispuestas en 2 hileras sobre el tallo, con las venas paralelas, divididas en 2 porciones, la inferior envuelve al tallo, más corta que el, y la parte superior muy larga, angosta, enrollada (las de las hojas inferiores arqueadas y dirigidas hacia el suelo); entre la vaina y la lámina. -

The Quarterly Journal of Oregon Field Ornithology

$4.95 The quarterly journal of Oregon field ornithology Volume 20, Number 4, Winter 1994 Oregon's First Verified Rustic Bunting 111 Paul Sherrell The Records of the Oregon Bird Records Committee, 1993-1994 113 Harry Nehls Oregon's Next First State Record Bird 115 Bill Tice What will be Oregon's next state record bird?.. 118 Bill Tice Third Specimen of Nuttall's Woodpecker {Picoides nuttallit) in Oregon from Jackson County and Comments on Earlier Records ..119 M. Ralph Browning Stephen P. Cross Identifying Long-billed Curlews Along the Oregon Coast: A Caution 121 Range D. Bayer Birders Add Dollars to Local Economy 122 Douglas Staller Where do chickadees get fur for their nests? 122 Dennis P. Vroman North American Migration Count 123 Pat French Some Thoughts on Acorn Woodpeckers in Oregon 124 George A. Jobanek NEWS AND NOTES OB 20(4) 128 FIELDNOTES. .131 Eastern Oregon, Spring 1994 131 Steve Summers Western Oregon, Spring 1994 137 Gerard Lillie Western Oregon, Winter 1993-94 143 Supplement to OB 20(3): 104, Fall 1994 Jim Johnson COVER PHOTO Clark's Nutcracker at Crater Lake, 17 April 1994. Photo/Skip Russell. CENTER OFO membership form OFO Bookcase Complete checklist of Oregon birds Oregon s Christmas Bird Counts Oregon Birds is looking for material in these categories: Oregon Birds News Briefs on things of temporal importance, such as meetings, birding trips, The quarterly journal of Oregon field ornithology announcements, news items, etc. Articles are longer contributions dealing with identification, distribution, ecology, is a quarterly publication of Oregon Field OREGON BIRDS management, conservation, taxonomy, Ornithologists, an Oregon not-for-profit corporation. -

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

Life History Account for Lesser Nighthawk

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group LESSER NIGHTHAWK Chordeiles acutipennis Family: CAPRIMULGIDAE Order: CAPRIMULGIFORMES Class: AVES B275 Written by: M. Green Reviewed by: L. Mewaldt Edited by: D. Winkler, R. Duke DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY An uncommon summer resident in arid lowlands, primarily in desert scrub, desert succulent shrub, desert wash, and alkali desert scrub habitats. Also forages over grasslands, desert riparian, and other habitats with high densities of flying insects. Occurs north in the Sacramento Valley to Tehama Co. (Grinnell and Miller 1944) and southern Shasta Co., and to lower Mono Co. east of the Sierra Nevada (McCaskie et al. 1979). More common in desert areas of southeastern California. Casual in winter mostly in southeastern deserts. Transients sometimes noted on the Channel Islands in spring and summer, and rare in spring on Farallon Islands (DeSante and Ainley 1980). SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Feeds on insects, which it hawks on long, low flights over open areas. Also makes short flights from the ground in the manner of a common poorwill (Bent 1940). Cover: Nests and roosts on bare sand and gravel surfaces; desert floor, along washes; sometimes uses levees and dikes for nesting. Forages over grasslands, open riparian areas, agricultural lands, and similar open habitats where insects thrive. Reproduction: Nests in the open on gravelly or sandy substrate. Also uses dikes and levees for nesting. Water: May drink while skimming over water surface (Bent 1940). Pattern: Undisturbed gravel or sand surface for roosting and nesting; open lowlands, riparian areas, agricultural fields, or other insect-rich areas for foraging. -

Using Structured Decision Making to Prioritize Species Assemblages for Conservation T ⁎ Adam W

Journal for Nature Conservation 45 (2018) 48–57 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal for Nature Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jnc Using Structured Decision Making to prioritize species assemblages for conservation T ⁎ Adam W. Greena, , Maureen D. Corrella, T. Luke Georgea, Ian Davidsonb, Seth Gallagherc, Chris Westc, Annamarie Lopatab, Daniel Caseyd, Kevin Ellisone, David C. Pavlacky Jr.a, Laura Quattrinia, Allison E. Shawa, Erin H. Strassera, Tammy VerCauterena, Arvind O. Panjabia a Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, 230 Cherry St., Suite 150, Fort Collins, CO, 80521, USA b National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, 1133 15th St NW #1100, Washington, DC, 20005, USA c National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, 44 Cook St, Suite 100, Denver, CO, 80206, USA d Northern Great Plains Joint Venture, 3302 4th Ave. N, Billings, MT, 59101, USA e World Wildlife Fund, Northern Great Plains Program, 13 S. Willson Ave., Bozeman, MT, 59715, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Species prioritization efforts are a common strategy implemented to efficiently and effectively apply con- Conservation planning servation efforts and allocate resources to address global declines in biodiversity. These structured processes help Grasslands identify species that best represent the entire species community; however, these methods are often subjective Priority species and focus on a limited number of species characteristics. We developed an objective, transparent approach using Prioritization a Structured Decision Making (SDM) framework to identify a group of grassland bird species on which to focus Structured decision making conservation efforts that considers biological, social, and logistical criteria in the Northern Great Plains of North America. The process quantified these criteria to ensure representation of a variety of species and habitats and included the relative value of each criterion to the working group. -

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California A Project of California Partners in Flight and PRBO Conservation Science The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California Version 2.0 2004 Conservation Plan Authors Grant Ballard, PRBO Conservation Science Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science Tom Gardali, PRBO Conservation Science Geoffrey R. Geupel, PRBO Conservation Science Tonya Haff, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Museum of Natural History Collections, Environmental Studies Dept., University of CA) Aaron Holmes, PRBO Conservation Science Diana Humple, PRBO Conservation Science John C. Lovio, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, U.S. Navy (Currently at TAIC, San Diego) Mike Lynes, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Hastings University) Sandy Scoggin, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at San Francisco Bay Joint Venture) Christopher Solek, Cal Poly Ponoma (Currently at UC Berkeley) Diana Stralberg, PRBO Conservation Science Species Account Authors Completed Accounts Mountain Quail - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Greater Roadrunner - Pete Famolaro, Sweetwater Authority Water District. Coastal Cactus Wren - Laszlo Szijj and Chris Solek, Cal Poly Pomona. Wrentit - Geoff Geupel, Grant Ballard, and Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science. Gray Vireo - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Black-chinned Sparrow - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Costa's Hummingbird (coastal) - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Sage Sparrow - Barbara A. Carlson, UC-Riverside Reserve System, and Mary K. Chase. California Gnatcatcher - Patrick Mock, URS Consultants (San Diego). Accounts in Progress Rufous-crowned Sparrow - Scott Morrison, The Nature Conservancy (San Diego). -

Inside Holy Cross - Inside

Inside Holy Cross - inside VOL. XXI, NO. 86 FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 6,1987 the independent student newspaper serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s Three platforms to run for SMC student body offices By MARILYN BENCHIK stated, “No experience necessary,” Assistant Saint Mary’s Editor and said, “ So, we’re just going to go for it.” Canidates for Saint Mary’s student Class officer canidates also attended body offices attended the second pre the Thursday night meeting. Running election information meeting Thursday for senior class officer positions are: night. Julie Bennett, Ana Cote, Patti Petro, Election hopefuls were required to at and Lorie Potenti. Potenti said they are tend only one of the two sessions. The not yet sure who will run for which po first pre-election meeting was held sition. Wednesday night. Sandy Cerimele, “ All four of us have had experience election commissioner, and Jeanne Hel in working with student government in ler, student body president, set the the last three years, and we feel we guidelines for campaigning have a great senior class. We want to procedures. make next year the most memorable,” The three platforms, each consisting Petro said. P of three canidates for the offices of Cote added, “Our experience is one president, vice president for student af of the most im portant factors to be con fairs, and vice president for academic sidered. We’ve already learned to deal affairs, are: Ann Rucker, Ann Reilly, with students’ problems and the issues and Ann Eckhoff; Sarah Cook, Janel which may arise.” Hamann, and Jill Hinterhalter; Eileen Canidates for the junior class posi Hetterich, Smith Hashagen, and Julie tions of president, vice president, sec Parrish. -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

98-100 OB Vol 16#2 Aug1998.Pdf

98 Photo Quiz Bob Curry Rather few of our birds sit length groups. Two species of nighthawks wise along branches as this bird is in the genus Chordeiles have doing. What we have is a dark and occurred in Ontario: the Common light bird with mottled, intricate Nighthawk, which unfortunately is plumage. It displays no legs and far less common than it once was, feet, a tiny somewhat hooked bill, a and the Lesser Nighthawk, which large-headed and no-necked occurred once at Point Pelee associ appearance, and rather long, point ated with a late April push of tropi ed wings. Moreover, it is sleeping! cal air. The other three are true Our only birds which combine nightjars, although two genera are these features are the Caprimulgi involved. Alas, the Whip-poor-will dae or nightjars. It is surprising to also is heard by fewer than it once consider that in a north temperate was in Ontario, but is nonetheless a eastern jurisdiction such as is widespread breeding inhabitant of Ontario, five species of goatsuckers southern and central Ontario. The have been recorded. Poorwill, a western species, has These may be divided into two occurred accidentally on the shore ONTARIO BIRDS AUGUST 1998 99 of James Bay, and the Chuck-will's and light buffy spots, whereas the widow, a denizen of the hot, humid somewhat less cryptic nighthawks southeastern U.S., has occurred in have plain black primaries. The summer (and bred) at a few wide underparts on nighthawks are spread locations, but remains an strongly barred blackish on white extremely rare bird, being recorded or pale buff. -

Sporobolus Latzii B.K.Simon (POACEAE)

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory Sporobolus latzii B.K.Simon (POACEAE) Conservation status Australia: Not listed Northern Territory: Vulnerable Photo: D. Albrecht Description less than 200 plants were found there. Given, however, that the region is relatively poorly Sporobolus latzii is a fairly robust erect tufted sampled (with less than two flora survey or perennial grass with flowering stems to collection points per 100 km2) the existence almost 1 m high from a short rhizome. The of additional populations cannot presently be leaves are minutely roughened, flat and to 16 ruled out. The swamps surveyed represent cm long and 3.5 mm wide. Spikelets are 2-2.3 approximately one third to one half of the mm long and arranged in a panicle 11-13 cm potential swamps in the region (P. Latz pers. long. The main branches of the inflorescence comm.). are solitary and spikelet-bearing throughout. Conservation reserves where reported: None Flowering: recorded in May. Distribution Sporobolus latzii is endemic to the Northern Territory (NT) where it is known only from the type locality in the Wakaya Desert (east of the Davenport Ranges and south of the Barkly Tablelands). The species was originally discovered in 1993 during a biological survey of the Wakaya Desert (Gibson et al. 1994). Some 40 swamps in the Wakaya Desert and additional similar Known locations of Sporobolus latzii swamps to the north of the Wakaya Desert were visited in the course of this survey work, Ecology but Sporobolus latzii was only found at the one Sporobolus latzii occurs in clay soil on the edge site (the type locality; P.Latz pers. -

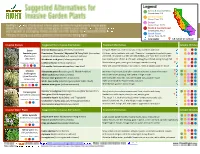

Suggested Non-Invasive Alternatives Invasive Grasses Suggested Non

Sierra & Coastal Mtns. (Sunset Zones 1-3) Central Valley (Sunset Zones 7-9) Desert (Sunset Zones 10-13) North & Central Coast (Sunset Zones 14-17) South Coast (Sunset Zones 18-24) Low water CA native or cultivar Invasive Grasses Suggested Non-invasive Alternatives Featured Information Suitable Climates Green Oriental fountain grass (Pennisetum orientale) Compact, floriferous, cold hardy, very similar aesthetic and habit fountain grass Pennisetum ‘Fireworks’,‘Skyrocket’ & ‘Fairy Tails’ (Pennisetum Cultivars, similar aesthetic and habit. ‘Fireworks’ is magenta striped with green (Pennisetum x advena, often mislabeled as P. setaceum cultivars) and white. ‘Skyrocket’ is green with white edges, and ‘Fairy Tails’ is solid green setaceum) Mendocino reed grass (Calamagrostis foliosa) Cool-season grass 1 ft. tall & 2 ft. wide. Arching flower heads spring through fall Invasive in climate zones: California fescue (Festuca californica) Shade tolerant grass, needs good drainage, tolerates mowing Pink muhly (Muhlenbergia capillaris 'Regal Mist’) Fluffy pink cloud-like blooms, frost tolerant, needs drainage, good en masse Mexican Blue grama grass (Bouteloua gracilis 'Blonde Ambition') Attractive flowerheads, best when cut back in winter, cultivar of CA native feathergrass Alkali sacaton (Sporobolus airoides) Robust yet slower growing, does well in a range of soils (Stipa/Nassella Mexican deer grass (Muhlenbergia dubia) Semi-evergreen mounder, likes well-drained soils, good en masse tenuissima) White awn muhly (Muhlenbergia capillaris 'White Cloud') Fluffy white cloud-like flower heads, easy care Invasive in climate zones: Autumn moor grass (Sesleria autumnalis) Neat clumper, good en masse, tough Pampas grass Foerster's reed grass (Calamagrostis x acutiflora 'Karl Foerster') Stately white plumes from summer until frost, durable and showy (Cortaderia selloana) Deer grass (Muhlenbergia rigens) Smaller form with simple, clean plumes, easy to grow Lomandra hystrix 'Katie Belles' and 'Tropicbelle' Tidy, tough, 4 ft.