Three Practices of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness: an Investigation in Comparative Soteriology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conversion to Tibetan Buddhism: Some Reflections Bei Dawei

4 Conversion to Tibetan Buddhism: Some Reflections Bei Dawei Abstract Tibetan Buddhism, it is often said, discourages conversion. The Dalai Lama is one of many Buddhist leaders who have urged spiritual seekers not to convert to Tibetan Buddhism, but to remain with their own religions. And yet, despite such admonitions, conversions somehow occur—Tibetan dharma centers throughout the Americas, Europe, Oceania, and East/Southeast Asia are filled with people raised as Jews, Christians, or followers of the Chinese folk religion. It is appropriate to ask what these new converts have gained, or lost; and what Tibetan Buddhism and other religions might do to better adapt. One paradox that emerges is that Western liberals, who recoil before the fundamentalists of their original religions, have embraced similarly authoritarian, literalist values in foreign garb. This is not simply an issue of superficial cultural differences, or of misbehavior by a few individuals, but a systematic clash of ideals. As the experiences of Stephen Batchelor, June Campbell, and Tara Carreon illustrate, it does not seem possible for a viable “Reform” version of Tibetan Buddhism (along the lines of Reform Judaism, or Unitarian Universalism) ever to arise—such an egalitarian, democratic, critical ethos would tend to undermine the institution of Lamaism, without which Tibetan Buddhism would lose its raison d’être. The contrast with the Chinese folk religion is less obvious, since Tibetan Buddhism appeals to many of the same superstitious compulsions, and there is little direct disagreement. Perhaps the key difference is that Tibetan Buddhism (in common with certain institutionalized forms of Chinese Buddhism) expands through predation upon weaker forms of religious identity and praxis. -

Thich Nhat Hanh the Keys to the Kingdom of God Jewish Roots

Summer 2006 A Journal of the Art of Mindful Living Issue 42 $7/£5 Thich Nhat Hanh The Keys to the Kingdom of God Jewish Roots The Better Way to Live Alone in the Jungle A Mindfulness Retreat for Scientists in the Field of Consciousness A Convergence of Science and Meditation August 19–26, 2006 Science studies the brain from your family to a seven-day mindfulness In the beautiful setting of Plum outside, but do we know what happens retreat to learn about our minds using Village, we will enjoy the powerful when we look inside to experience Buddhist teachings and recent scientific energy of one hundred lay and mo- our own minds? Ancient Buddhist findings. nastic Dharma teachers, and enjoy the wisdom has been found to correspond brotherhood and sisterhood of living in During the retreat participants very closely with recent scientific dis- community. Lectures will be in English are invited to enjoy talks by and pose coveries on the nature of reality. Dis- and will be simultaneously translated questions to Zen Master Thich Nhat coveries in science can help Buddhist into French and Vietnamese. Hanh. Although priority will be given meditators, and Buddhist teachings on to neuroscientists and those who work consciousness can help science. Zen in the scientific fields of the brain, the Master Thich Nhat Hanh and the monks mind, and consciousness, everyone is and nuns of Plum Village invite you and welcome to attend. For further information and to register for these retreats: Upper Hamlet Office, Plum Village, Le Pey, 24240 Thenac, France Tel: (+33) 553 584858, Fax: (+33) 553 584917 E-mail: [email protected] www.plumvillage.org Dear Readers, Hué, Vietnam, March 2005: I am sitting in the rooftop restaurant of our lovely hotel overlooking the Perfume River, enjoying the decadent breakfast buffet. -

Sikkim: the Hidden Land and Its Sacred Lakes

- SIKKIM- The Hidden Holy Land And Its Sacred Lakes Dr. Chowang Acharya & Acharya Sonaro Gyatso Dokharn Various religious textual sources ascertain the fact that Sikkim is one of the sacrosanct hidden Buddhist zones recognized by Guru Padmasambhava, the fountainhead of Tantrayana Buddhism. Denjong Nye-Yig (The Pilgrim's Guide to the Hidden Land of Sikkim), by Lhatsun Jigmed Pawo, based on Lama Gongdu Cycle revealed by Terton Sangay Lingpa (1340-1396) has the following description of Sikkim: "~:n'4~rs~ 'a;~~1 ~~'~o,j'~~ 'ffi~ 'Q,S~'5f~4~~'~~'$'~1 ~s~~'~' qr.;'~~'~~'l:.Jl ~~o.J·UJ~'~~'~f.:1o,j'~'d;f~~l ~~~~'~~~'~'f~q'o,j'~~' ~'~1 ~r~:~5f[lJ~·~~'o,j·~ry~·l:.Jl f~~'~~l~~~'~'~'o,j'~ry~l ~q. il~·~·~~'~~'~'o,j'~ry~'l:.Jl S~'~~~'o.Jg.ii~'~~~'o,j'~ry~l ~~'l:.J~.~, S~'4~ ·o.J~~·~·~~'~'o,j'~ry~'l:.Jl o.J~Q, 'f~~'f~~'Q,~~ 'a:)~ 'o,j'~ry~ 'l:.Jl f~f.:1~'UJ~'l Q,~~'~~'C:iT-Q,S~'~~'UJ~'~'~Q,'Q,S~'5Jj UJ~~'4~'ffi'~~' ~4~~1 ~ 'W~ '~~'~o,j'Q,S~'5f~4~~'~~':n~~1 " "The auspicious Hidden Land ofSikkim, having a square topographical ap pearance, is situated in the southwest ofSamye Monastery, Lhasa, TIbet, and is 10 SIKKIM- THE HIDDEN HOLY LAND close to the southwest flce ofMt. Kyin-thing. Its eastern border touches Mt. Sidhi of India; the western border touches the mountain of Zar district of u- Tsang, Tibet, and the Northern border touches Lake Tsomo Dri-Chu': "The upper range ofthe country, the northeastern side, reaches up to Gangchen Zod-nga and the lower southwesterly range touches Banga (India). -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

Secularism and the Buddhist Monastery of Pema Yangtse in Sikkim'

MELANIE V ANDENHELSKEN 55 SECULARISM AND THE BUDDHIST MONASTERY OF PEMA YANGTSE IN SIKKIM' MELANIE V ANDENHELSKEN Montpellier Thutob Namgyal and Yeshe Dolma's2 account of the founding of the kingdom of Sikkim, shows us a politico-religious system in line with the concept of separate spiritual and temporal domains such as encountered in Tibet.3 However, this concept is very distinct from the Indian notion of secularism, which can be formulated as a privatisation of the religious sphere.4 Indeed, the absolute separation of the lay and religious domains appears to be equally problematic in both Sikkim and Tibet.5 The functioning of the royal monastery of Pemayangtse in Sikkim clearly demonstrates that there can be many interpenetrations of these two domains (that we can also refer to as conjugation), and which are not at variance with certain Buddhist concepts. The relationship that existed between Pemayangtse monastery and the kingdom of Sikkim represents one of the forms of this interpenetration in the Tibetan cultural area. When considering the functioning of Pemayangtse today and in the past, I will examine the relationship between the monastery and the I This paper is adapted from my doctoral thesis entitled: Le monastere bouddhique de Pemayangtse au Siklam (Himalaya oriental, Inde) : un monastere dans le monde. This thesis is the result of two years of fieldwork in India (1996-1997 and 1998- 1999), financed by an Indo-French grant from the French Department of Foreign Affairs and the ICCR, Delhi. My long stay in Sikkim was made possible thanks to the Home Ministry of Sikkim and the Institute of Higher Nyingma Studies, Gangtok. -

Groundwork Buddhist Studies Reader

...thus we have heard... (may be reproduced free forever) Buddhist Studies Reader Published by: Groundwork Education www.layinggroundwork.org Compiled & Edited by Jeff Wagner Second Edition, May 2018 This work is comprised of articles and excerpts from numerous sources. Groundwork and the editors do not own the material, claim copyright or rights to this material, unless written by one of the editors. This work is distributed as a compilation of educational materials for the sole use as non-commercial educational material for educators. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free to edit and share this work in non-commercial ways. Any published derivative works must credit the original creator and maintain this same Creative Commons license. Please notify us of any derivative works or edits. "53 Wearing the broad-brimmed hat of the west, symbolic of the forces that guard the Buddhist Studies Reader wilderness, which is the Natural State of the Dharma and the true path of man on Earth: Published by Groundwork Education, compiled & edited by Jeff Wagner all true paths lead through mountains-- The Practice of Mindfulness by Thích Nhất Hạnh ..................................................1 With a halo of smoke and flame behind, the forest fires of the kali-yuga, fires caused by Like a Leaf, We Have Many Stems by Thích Nhất Hạnh ........................................4 the stupidity of those who think things can be gained and lost whereas in truth all is Mindfulness -

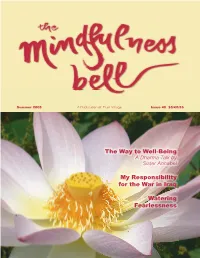

The Way to Well-Being My Responsibility for the War in Iraq

Summer 2008 A Publication of Plum Village Issue 48 $8/%8/£6 The Way to Well-Being A Dharma Talk by Sister Annabel My Responsibility for the War in Iraq Watering Fearlessness ISSUE NO. 48 - SUMMER 2008 Dharma Talk 4 Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh Talks about Tibet 6 The Way to Well-Being By Sister Annabel, True Virtue War’s Aftermath 12 A War Is Never Over Healing and Transformation By Trish Thompson 29 The First Precept 14 Question By Julie Hungiville LeMay By Paul Davis 30 The Leaves of One Tree 15 Spanning a Bridge By Le Thu Thuy By Sister Dang Nghiem 32 On Love and Being Gay 18 “First Time in Vietnam?” By Laurie Arron By Brian McNaught 34 Blue Sky Practice By Susan Hadler Heart to Heart 35 The Fifth Mindfulness Training By Evelyn van de Veen, Scott Morris, and Paul Baranowski Children’s Wisdom 37 Paint a Portrait of Me By Brooke Mitchell 38 The Helping Hand By Brother Phap Dung 40 Bell of Mindfulness By Terry Cortes-Vega 20 My Responsibility for the War in Iraq Sangha News By Bruce Campbell 41 Thay Rewrites the Five Contemplations; New Dharma Teachers Ordained at Plum Village; 20 The Light at the Q&A about Blue Cliff Tip of the Candle By Claude Anshin Thomas Book Reviews Gift of Non-Fear 44 World As Lover, World As Self By Joanna Macy 23 Getting Better, not Bitter The Dharma in Tanzania 44 Buddha Mind, Buddha Body By Thich Nhat Hanh By Karen Brody 25 Watering Fearlessness By David C. -

Copper Mountain

A Free Article from The Shamanism Magazine You may share this article in any non-commercial way but reference to www.SacredHoop.org must be made if it is reprinted anywhere. (Please contact us via email - found on our website - if you wish to republish it in another publication) Sacred Hoop is an independent magazine about Shamanism and Animistic Spirituality. It is based in West Wales, and has been published four times a year since 1993. To get a very special low-cost subscription to Sacred Hoop - please visit : www.SacredHoop.org/offer.html We hope you enjoy reading the article. Nicholas Breeze Wood (editor) hether seen from a Buddhist or shamanic Wviewpoint, Padmasambhava is a being who is able to manipulate reality and the beings who dwell in it in a very magical way, and there is no doubt that the teachings left by him have great power. He is an extremely important figure in Tibetan Buddhism, being the tantric Buddha, and sometimes is reffered to as Padmakara or Guru Rinpoche. As the ‘First Shaman’ he provides a role model for practitioners and the many legends that surround him link back to the pre-historic shamanic world of the Himalayas. These legends were recorded by his Tibetan consort Yeshe Tsogyal after he came to Tibet in the 9th century, and his birth was predicted by the Buddha, who, before he died, said that one even greater than himself would be born in a lotus flower to teach the ways of tantra. PADMASAMBHAVA’S LIFE Guru Rinpoche’s story began at the ‘Ocean of Milk’ or Lake Danakosha in the Land of Odiyana on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, where according to legend, in the reign of king Indrabodhi, he appeared miraculously in a beautiful red lotus blossom, as an eight-year-old child holding a dorje (see picture) and a lotus. -

2018 Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche in Delhi, India

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche in Delhi, India. Photo by Alexvi. RINPOCHE’S REMARKS While it’s important for all human beings to bring reason to every avenue of their lives—social, political, and spiritual— academics particularly treasure, cherish, and nurture the critical, rational, and analytical faculties. In that regard, Buddhist studies have such sophisticated tools for sharpening our critical thinking that they even lead us to critique the critical mind itself. In this world and era of short attention spans, where we are so influenced by headlines, images, and sound bites and swayed by emotion, it’s ever more important to support and cultivate genuine traditions of critical thinking. That is also of paramount importance for followers of Shakyamuni Buddha who cherish his teachings. The traditional approach to the Buddhist path recognizes that a complete understanding and appreciation of the teachings cannot happen through academic and intellectual study alone, but requires us to practice the teachings and bring them into our lives. Prior to such practice, however, it has always been emphasized that hearing and contemplating the teachings is of the utmost importance. In short, study and critical analysis of the Buddhist teachings are as necessary for dedicated practitioners as they are valuable for scholars, leaders, and ordinary people the world over. —Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, in his remarks announcing the Khyentse Gendün Chöpel Professorship of Tibetan Buddhist Studies at the University of Michigan, June, 2018 3 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Sharing Buddha’s Wisdom with Everyone Dear friends and supporters of Khyentse Foundation, As Khyentse Foundation enters its 18th year of operation, I wish to take In managing the activities of the foundation, we try to maintain both an the opportunity to share some thoughts on the basic questions of who open mind and a critical approach. -

Reading Maxine Hong Kingston's the Fifth Book of Peace

UC Santa Barbara Journal of Transnational American Studies Title Life, Writing, and Peace: Reading Maxine Hong Kingston's The Fifth Book of Peace Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/68t2k01g Journal Journal of Transnational American Studies, 1(1) Author Shan, Te-Hsing Publication Date 2009-02-16 DOI 10.5070/T811006948 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Life, Writing, and Peace: Reading Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Fifth Book of Peace TE‐HSING SHAN I. A Weird and Intriguing Text “If a woman is going to write a Book of Peace, it is given her to know devastation”— thus begins Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Fifth Book of Peace (2003).1 Unlike her former award‐winning and critically acclaimed works—The Woman Warrior (1976), China Men (1980), and Tripmaster Monkey: His Fake Book (1989)—the reception of her latest book has been cool, to say the least. As of November 2008, there were only three entries on The Fifth Book of Peace in the MLA International Bibliography, in sharp contrast to the numbers on The Woman Warrior (273 entries), China Men (90 entries), and Tripmaster Monkey (63 entries). These three entries include an eight‐page book essay published in China, a twelve‐page journal article on Kingston’s three works published in Turkey, and a U.S. dissertation on three Asian American female writers. In addition, there are very few reviews in newspapers and journals. This is indeed a phenomenon unthinkable for a writer who has been hailed as one of the most frequently taught writers living in the U.S. -

A Psychological Analysis of Physical and Mental Pain in Buddhism Ashin

A Psychological Analysis of Physical and Mental Pain in Buddhism Ashin Sumanacara1 Mahidol University, Thailand. Pain is a natural part of life and all of us. Ordinary people are inflicted with physical or mental pain. In this paper, firstly we will analyse the concept of physical and mental pain according to the Pali Nikāyas. Next we will discuss the causes of physical and mental pain, and investigate the unwholesome roots: greed (lobha), hatred (dosa) and delusion (moha), and their negative roles in causing physical and mental pain. Then we will highlight the Buddhist path to overcoming physical and mental pain. Finally we will discuss mindfulness and the therapeutic relationship. Mindfulness, as it is understood and applied in Buddhism, is a richer theory than thus far understood and applied in Western psychotherapy. Within Buddhism the development of mindfulness must be understood to be interrelated with the maturity of morality (sīla), concentration (samādhi) and wisdom (paññā). A Word about Buddhism Buddhism, a spiritual movement, arose from the prevalent intellectual, political and cultural milieu of Indian society in the 6th century BCE and has been an influential cultural force in Asia for more than 2550 years. In recent decades, it has gained acceptance in the West, largely due to its solution of mental pain of human beings through mindfulness meditation. The core teachings of the Buddha are contained in the Four Noble Truths, which are as follows: (1) Dukkha: life is characterized by pain; (2) Samudaya: the cause of pain which is craving (taṇhā); (3) Nirodha: pain can be ended by the cessation of craving; and (4) Magga: there is a way to achieve the cessation of pain, which is the Noble Eightfold Path (ariya-aṭṭhangika-magga). -

Guru Padmasambhava and His Five Main Consorts Distinct Identity of Christianity and Islam

Journal of Acharaya Narendra Dev Research Institute l ISSN : 0976-3287 l Vol-27 (Jan 2019-Jun 2019) Guru Padmasambhava and his five main Consorts distinct identity of Christianity and Islam. According to them salvation is possible only if you accept the Guru Padmasambhava and his five main Consorts authority of their prophet and holy book. Conversely, Hinduism does not have a prophet or a holy book and does not claim that one can achieve self-realisation through only the Hindu way. Open-mindedness and simultaneous existence of various schools Heena Thakur*, Dr. Konchok Tashi** have been the hall mark of Indian thought. -------------Hindi----cultural ties with these countries. We are so influenced by western thought that we created religions where none existed. Today Abstract Hinduism, Buddhism and Jaininism are treated as Separate religions when they are actually different ways to achieve self-realisation. We need to disengage ourselves with the western world. We shall not let our culture to This work is based on the selected biographies of Guru Padmasambhava, a well known Indian Tantric stand like an accused in an alien court to be tried under alien law. We shall not compare ourselves point by point master who played a very important role in spreading Buddhism in Tibet and the Himalayan regions. He is with some western ideal, in order to feel either shame or pride ---we do not wish to have to prove to any one regarded as a Second Buddha in the Himalayan region, especially in Tibet. He was the one who revealed whether we are good or bad, civilised or savage (world ----- that we are ourselves is all we wish to feel it for all Vajrayana teachings to the world.