Emergency Remote Teaching in Higher Education: How Academics Identify the Educational Possibilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

YouStarKaraoke.com Songs by Artist 602-752-0274 Title Title Title 1 Giant Leap 1975 3 Doors Down My Culture City Let Me Be Myself (Wvocal) 10 Years 1985 Let Me Go Beautiful Bowling For Soup Live For Today Through The Iris 1999 Man United Squad Loser Through The Iris (Wvocal) Lift It High (All About Belief) Road I'm On Wasteland 2 Live Crew The Road I'm On 10,000 MANIACS Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I M Gone Candy Everybody Wants Doo Wah Diddy When I'm Gone Like The Weather Me So Horny When You're Young More Than This We Want Some PUSSY When You're Young (Wvocal) These Are The Days 2 Pac 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Trouble Me California Love Landing In London 100 Proof Aged In Soul Changes 3 Doors Down Wvocal Somebody's Been Sleeping Dear Mama Every Time You Go (Wvocal) 100 Years How Do You Want It When You're Young (Wvocal) Five For Fighting Thugz Mansion 3 Doors Down 10000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Road I'm On Because The Night 2 Pac & Eminem Road I'm On, The 101 Dalmations One Day At A Time 3 LW Cruella De Vil 2 Pac & Eric Will No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 10CC Do For Love 3 Of A Kind Donna 2 Unlimited Baby Cakes Dreadlock Holiday No Limits 3 Of Hearts I'm Mandy 20 Fingers Arizona Rain I'm Not In Love Short Dick Man Christmas Shoes Rubber Bullets 21St Century Girls Love Is Enough Things We Do For Love, The 21St Century Girls 3 Oh! 3 Wall Street Shuffle 2Pac Don't Trust Me We Do For Love California Love (Original 3 Sl 10CCC Version) Take It Easy I'm Not In Love 3 Colours Red 3 Three Doors Down 112 Beautiful Day Here Without You Come See Me -

PHIL WOODS NEA Jazz Master (2007)

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. PHIL WOODS NEA Jazz Master (2007) Interviewee: Phil Woods (November 2, 1931 - ) Interviewer: Marty Nau and engineered by Ken Kimery Date: June 22-23, 2010 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 66 pp. Marty Nau [MN]: Okay, this is Marty Nau here with the Smithsonian interviewing Phil Woods, a certain dream of mine come true. And Phil for the national record … Phil Woods [PW]: Yes, sir. [MN]: … for the Smithsonian they’d like to have you state your full name. [PW]: Gene Quill [laughs]. No, I’m, I’m Phil Woods. I was born in uh 1931. Uh, November second, which means today I’m 78 but I’m very happy to say I have the body of a 77-year-old man. [MN]: I noticed that immediately. [PW]: I was born in Springfield, Massachusetts. I have one brother, seven years older. And uh, any other facts you’d like to have? [MN]: Well, uh could you talk about your parents? [PW]: My parents. Well, my dad was reported to be a violin player when he was a kid. Um, music was very important in our family. My mom loved music. Uh [mumbles] there were four or five sisters and on my father’s side there was an uncle who played saxophone and one of my mother’s sister’s husbands played saxophone and that’s how I, I was given the sax in the will when he died. -

View Song List

Piano Bar Song List 1 100 Years - Five For Fighting 2 1999 - Prince 3 3am - Matchbox 20 4 500 Miles - The Proclaimers 5 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin' Groovy) - Simon & Garfunkel 6 867-5309 (Jenny) - Tommy Tutone 7 A Groovy Kind Of Love - Phil Collins 8 A Whiter Shade Of Pale - Procol Harum 9 Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) - Nine Days 10 Africa - Toto 11 Afterglow - Genesis 12 Against All Odds - Phil Collins 13 Ain't That A Shame - Fats Domino 14 Ain't Too Proud To Beg - The Temptations 15 All About That Bass - Meghan Trainor 16 All Apologies - Nirvana 17 All For You - Sister Hazel 18 All I Need Is A Miracle - Mike & The Mechanics 19 All I Want - Toad The Wet Sprocket 20 All Of Me - John Legend 21 All Shook Up - Elvis Presley 22 All Star - Smash Mouth 23 All Summer Long - Kid Rock 24 All The Small Things - Blink 182 25 Allentown - Billy Joel 26 Already Gone - Eagles 27 Always Something There To Remind Me - Naked Eyes 28 America - Neil Diamond 29 American Pie - Don McLean 30 Amie - Pure Prairie League 31 Angel Eyes - Jeff Healey Band 32 Another Brick In The Wall - Pink Floyd 33 Another Day In Paradise - Phil Collins 34 Another Saturday Night - Sam Cooke 35 Ants Marching - Dave Matthews Band 36 Any Way You Want It - Journey 37 Are You Gonna Be My Girl? - Jet 38 At Last - Etta James 39 At The Hop - Danny & The Juniors 40 At This Moment - Billy Vera & The Beaters 41 Authority Song - John Mellencamp 42 Baba O'Riley - The Who 43 Back In The High Life - Steve Winwood 44 Back In The U.S.S.R. -

Head Coach Kathy Mcconnell-Miller Season

Fifth Head Coach Kathy McConnell-Miller Season When Kathy McConnell- including the 2008 WNIT run, before returning to her native Miller took over the University Latvia to pursue a professional career. In 2008, the Buffaloes of Colorado program four years landed the consensus Colorado Player of the Year Alyssa Fressle ago, there’s no question the out of Highlands Ranch, who made an immediate contribution Buffaloes were rebuilding and and was rewarded with a spot on the Big 12 All-Rookie Team. the team was a work in CU hit the state jackpot in 2009 with three All-Colorado cal- progress. iber players; twins Meagan and Brenna Malcolm-Peck, Boulder In four seasons at Colorado, natives who played at Horizon High School, and Chucky Jeffery, there is no question that one of the top Class 4A players in 2009 for Sierra High School McConnell-Miller’s Buffaloes in Colorado Springs. The have made progress and the regional additions of program his heading in the right Kailah Bailey and Melissa direction. MacFarlane, both of McConnell-Miller, 41, sports a Omaha, Neb., have given 52-71 record in her four seasons at Colorado and is 143-159 the Buffaloes their third overall in 10 seasons as an NCAA Division I head coach. Top 40 class in the last Injuries, graduation and playing in the nation’s premier four years. women’s basketball conference, the Big 12, hampered the In 2006, Colorado had progress her teams had built her first three seasons in 2008-09 the No. 29 ranked class as the Buffaloes struggled to an 11-18 mark and a 12th place according to the All-Star finish in league play. -

Popular Wedding Covers (346)

The Atlanta Wedding Band is proud to have performed over 100 weddings since the beginning of 2011. We have the distinct honor of being a 5 star band on www.gigmasters.com, not only that, but every client that has booked us through that site has given us 5 out of 5! Atlanta Wedding Band 1418 Dresden Drive Unit 365, Atlanta, Georgia, 30319, United States. 404-272-0337 Popular Wedding Covers (346) For an all inclusive list (700+), scroll further down! Motown/R&B/Funk/Dance (53) Al Green Let’s Stay Together Aretha Franklin Ain’t No Mountain High Enough BeeGees Stayin Alive Ben E. King Stand by Me Beyonce Knowles Irreplaceable Bill Withers Ain’t No Sunshine Lean On Me Black Eyed Peas I Got a Feeling Bruno Mars (Mark Ronson) Marry You Uptown Funk Cee-Lo Green Forget You Chubby Checker The Twist The Commodores Brick House The Contours Do You Love Me Cupid Cupid Shuffle Dexy’s Midnight Runners Come on Eileen Earth Wind and Fire September The Foundations Build me Up Buttercup The Four Tops I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar pie, Honey Bunch) Hall and Oates You Make My Dreams The Isley Brothers Shout Jackson 5 ABC I Want You Back James Brown I Feel Good Jason Derulo It Girl Want to Want Me Kenny Loggins Footloose King Harvest Dancing in the Moonlight Kool and the Gang Celebration Lionel Ritchie All Night Long Louis Armstrong What a Wonderful World Marvin Gaye How Sweet It Is Let’s Get it On Sexual Healing Michael Jackson Billie Jean Man in the Mirror Otis Redding Sittin on the Dock of the Bay Outkast Hey Ya Sorry Ms. -

Skyline Orchestras Rhapsody

Skyline Orchestras Proudly Presents Rhapsody Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, you’ll be viewing the band Rhapsody, led by Charlie D’Oria and Greg Warno. Rhapsody has been performing successfully in the wedding industry for over 20 years. Their experience and professionalism will ensure a great party and a memorable occasion for you and your guests. Who is Rhapsody? Charlie D’Oria……....Lead Vocals, Bass Guitar & Acoustic Guitar Ellen Dumlao………..Female Lead Vocalist & Percussion Will Coleman.……….Male Lead Vocalist & Master of Ceremonies Greg Warno…………..Lead Vocals, Keyboards, Trumpet Steve Briody.…………Guitars and Background Vocals Jon Pereira……………Saxophones & Guitar Paul Caputo…..………Drums & Percussion Joe Citrano……………Trombone and Background Vocals In addition to the music you’ll be hearing tonight, we’ve supplied a song playlist for your convenience. Our repertoire has taken us from Pitbull to Ke$ha, Luke, Bryan to Zac Brown Band, Rhianna to Bon Jovi, Barry White to Sinatra, Lady Gaga to Beyonce, Bruno Mars to Paramore, Neo to Maroon 5. The list is just a part of what the band has done at prior affairs. If you don’t see your favorite songs listed, please ask. Every concern and detail for your musical tastes will be held in the highest regard. Please inquire regarding the many options available. Thank you once again for listening…..Good Luck and enjoy the show! See us at skylineorchestras.com (631) 277-7777 DANCE Dance To The Music—Sly & Family Stone Dance Into The Light – Phil Collins 867-5309- -

Soul Ukulele Songbook

Compiled and arranged by Spencer Gay The Copyrighted songs provided free herein are for education and thus fall under FAIR USE This book is not for sale SOUL SONGS 35 It’s the Same Old Song 1 Ain't No Sunshine 36 I’ve Been Loving You 2 Ain’t Too Proud to Beg 37 Just My Imagination 3 Baby I Need Your Lovin' 38 Just One Look 4 Baby I’m Yours 39 LA La Means I love You 5 Baby, It's You 40 Lean on Me 6 Baby Love 41 Let the Good Times Roll 7 Be My Baby 42 Let’s Get it On 8 Bring It on Home to Me 44 Let’s Stay Together 9 Build Me Up Buttercup 45 Lipstick Traces 10 Celebration 46 The Loco-motion 11 Chapel of Love 47 Lonely Teardrops 12 Come See About Me 48 Mama Said 13 Cupid 49 Money – That’s What I Want 14 Da Do Ron Ron 50 Money, Honey 15 Dancing in the Street 51 Mustang Sally 16 Do You Love Me 52 My Girl 17 Easy 53 My Guy 18 Fever 54 Ninety-Nine and a Half 19 For Once in My Life 55 Nowhere to Run 20 Get Ready 56 Ooh, Baby Baby 21 Heat Wave 57 On Broadway 22 Hi-Heel Sneakers 58 One Fine Day 23 Higher and Higher 59 People Get Ready 24 How Sweet it Is 60 Please, Please, Please 25 I Can't Help Myself 61 Please Mr. Postman 26 I Heard It Through the Grapevine 62 Rainy Night in Georgia 28 (Reach Out) I’ll Be There 63 Rescue Me 30 I Know (You Don’t Love Me No More) 64 Shama lama Ding Dong 31 I'm Losing You 65 Signed Sealed Delivered, I’m Yours 32 I’m Stone in Love with You 66 Sittin’ On the Dock of The Bay 33 If You Don’t Know Me by Now 67 So Fine 34 In the Midnight Hour 68 Someday, We’ll Be Together Ain't No Sunshine 1971 Bill Withers Intro below Strum=D DU UD First note=E Am Em7 Bm Am Ain't no sunshine when she's gone. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

![[History of New Hampshire College]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9389/history-of-new-hampshire-college-4299389.webp)

[History of New Hampshire College]

Author's Note New Hampshire College will always be a place that is special to me. It is my hope that I am able to convey to the reader some of its singular qualities. In talking to different people, it was soon apparent that each person has his or her version of the past. So although I have included facts and figures, the major emphasis in this history is on people's reflections of what they saw and felt. It is in this manner that New Hampshire College can be best depicted, because New Hampshire College is the story of people and how their dreams were realized. Dr. Everitt Sackett (d.o.b. and d.o.d.), was a member of New Hampshire College's Board of Trustees at his death. He was the Executive Secretary of the Coordinating Board of Higher Education and was also the Dean of the School of Liberal writingsArts anda t the University of New Hampshire. I am indebted to him for his extremely extensive research into the papers and archives of New Hampshire College. Without his valuable work, I could not have undertaken this book. My Mother's recall and recollections are an essential part of this account. She was remarkable in the how much she remembered and in the detail in which she remembered it. Whenever I had a question, I turned to her. Mostly, she remembered. On the occasions that she did not, she graciously did the research. I also thank my brother for his time and extremely valuable contributions. He was able to synthesize and make connections to seemly disparate events were extremely important in helping to unify this book. -

The Mississippi Mass Choir

R & B BARGAIN CORNER Bobby “Blue” Bland “Blues You Can Use” CD MCD7444 Get Your Money Where You Spend Your Time/Spending My Life With You/Our First Feelin's/ 24 Hours A Day/I've Got A Problem/Let's Part As Friends/For The Last Time/There's No Easy Way To Say Goodbye James Brown "Golden Hits" CD M6104 Hot Pants/I Got the Feelin'/It's a Man's Man's Man's World/Cold Sweat/I Can't Stand It/Papa's Got A Brand New Bag/Feel Good/Get on the Good Foot/Get Up Offa That Thing/Give It Up or Turn it a Loose Willie Clayton “Gifted” CD MCD7529 Beautiful/Boom,Boom, Boom/Can I Change My Mind/When I Think About Cheating/A LittleBit More/My Lover My Friend/Running Out of Lies/She’s Holding Back/Missing You/Sweet Lady/ Dreams/My Miss America/Trust (featuring Shirley Brown) Dramatics "If You come Back To Me" CD VL3414 Maddy/If You Come Back To Me/Seduction/Scarborough Faire/Lady In Red/For Reality's Sake/Hello Love/ We Haven't Got There Yet/Maddy(revisited) Eddie Floyd "Eddie Loves You So" CD STAX3079 'Til My Back Ain't Got No Bone/Since You Been Gone/Close To You/I Don't Want To Be With Nobody But You/You Don't Know What You Mean To Me/I Will Always Have Faith In You/Head To Toe/Never Get Enough of Your Love/You're So Fine/Consider Me Z. Z. -

Too Many 45 Parties, Too Many Pals Page 2 of 43

Page 1 of 43 **01 Too Many 45 Parties, Too Many Pals Page 2 of 43 **01 Too Many 45 Parties, Too Many Pals Artist Name 1415 songs, 2.6 days, 5.59 GB Alvin Robinson Something You Got Alvin Robinson Let Me Down Easy Artist Name Alvin Robinson Baby Don't You Do It A.C. Reed Talkin' About My Friends Alvin Robinson Something You Got Aarch Hall Jr. Konga Joe Alvin Robinson Let The Good Times Roll Aarch Hall Jr. Monkey In My Hat Band American Spring Fallin' In Love The Abstracts Smell of Incense Amos Milburn Jr. Gloria The Ad Libs Kicked Around Andre Williams Humpin', Bumpin' and Thumping The African Beavers Find My Baby Andre Williams Sweet Little Pussycat The African Beavers You Got Something Andre Williams Just Because of a Kiss The African Beavers Night Time Is the Right Time Andre Williams Bacon Fat The African Beavers Jungle Fever Andre Williams (Mr. Rhythm) with Vocal Group Mean Jean Al Casey and the K-C-Ettes What Are We Gonna Do In '64? Andre Williams with the Don Juans Going Down to Tia Juana Al Casey with the K-C-Ettes Surfin' Hootenanny Angel Down We Go (From The Orig. Soundtrack Of The A.… Angel, Angel Down We Go Al Davis Go Baby Go Angie Caroll Sleep Little Children Al Ferrier Yard Dog Angie Caroll Ah Baby, That's Nice Al Green Sweet As Love, Strong As Death Ann Sexton Have a Little Mercy Al Green I'm Glad You're Mine Ann-Margret It's a Nice World To Visit (But Not To Live In) Al Perkins Need To Belong Apollos That's the Breaks Al Quick and The Masochists Theme From The Sadistic Hypnotist The Arbors Touch Me Al Terry Watch Dog Aretha Franklin One Step Ahead Alan Pierce Swampwater Aretha Franklin I Can't Wait Until I See My Baby's Face Alan Vega Jukebox Babe Arondies 69 Albert Collins Conversation With Collins Arthur Ponder Dr. -

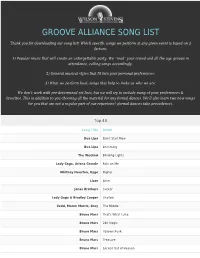

Groove Alliance Song List

GROOVE ALLIANCE SONG LIST Thank you for downloading our song list! Which specific songs we perform at any given event is based on 3 factors: 1) Popular music that will create an unforgettable party. We “read” your crowd and all the age groups in attendance, calling songs accordingly. 2) General musical styles that fit into your personal preferences. 3) What we perform best; songs that help to make us who we are. We don’t work with pre-determined set lists, but we will try to include many of your preferences & favorites. This in addition to you choosing all the material for any formal dances. We’ll also learn two new songs for you that are not a regular part of our repertoire! (formal dances take precedence). Top 40 Song Title Artist Dua Lipa Don't Start Now Dua Lipa Levitating The Weeknd Blinding Lights Lady Gaga, Ariana Grande Rain on Me Whitney Houston, Kygo Higher Lizzo Juice Jonas Brothers Sucker Lady Gaga & Bradley Cooper Shallow Zedd, Maren Morris, Grey The Middle Bruno Mars That's What I Like Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Bruno Mars Just The Way You Are Ariana Grande Break Free Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Suit and Tie DNCE Cake By The Ocean James Arthus Say You Won't Let Go Ed Sheeran Shape Of You Ed Sheeran Perfect Ed Sheeran Thinkin’ Out Loud Leon Bridges Beyond Leon Bridges Coming Home OMI Cheerleader Pitbull Fireball The Weeknd Can't Feel My Face Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance Calvin Harris How Deep Is Your Love? Beyoncé Love On Top Taylor Swift Shake It Off Rihanna Only Girl In The World Rihanna We Found Love Meghan Trainor Lips Are Movin’ Meghan Trainor All About The Bass Meghan Trainor ft.