Is That Racist?: One White Family Interrogating Whiteness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigating Black Identity Development: the Power of Interactive Multicultural Read Alouds with Elementary-Aged Children

education sciences Article Navigating Black Identity Development: The Power of Interactive Multicultural Read Alouds with Elementary-Aged Children Rebekah E. Piper College of Education and Human Development, Texas A&M University-San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78224, USA; [email protected] Received: 9 April 2019; Accepted: 23 April 2019; Published: 18 June 2019 Abstract: Racial identity development in young children is influenced by interactions with teachers and curriculum in schools. This article, using the framework of critical race theory, critical literacy, and critical pedagogy, explores how three elementary-aged Black children view their own identity development. Specifically, observing how children interact with Movement-Oriented Civil Rights-Themed Children’s Literature (MO-CRiTLit) in the context of a non-traditional summer literacy program, Freedom Schools, to influence their Black identity. Professional development and preservice teacher preparation are needed to support teachers as they navigate through learning about pedagogical practices that increase student engagement. Keywords: critical literacy; Civil Rights; Black identity; children 1. Introduction The central question addressed by the Supreme Court during the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954) [1] was whether the segregation of children in public schools based on their race, deprived minoritized children of equal educational opportunities when everything else was equal [2–4]. This question has been, and continues to be, answered in the negative, as evidenced in an educational system in which Children of Color are repeatedly reported to have lower reading and numeracy scores in comparison to their white peers. In 2003, Education Trust, Inc. reported that, nationally, fourth-grade African-Americans fell behind their white peers in reading. -

THAT WILL CHANGE YOUR LIFE FOREVER! >> HSM Pastor Eric

Deeper Faith Kit: Matthew & Mark // Purpose Church // HSM START SOMETHING TODAY THAT WILL CHANGE YOUR LIFE FOREVER! >> HSM Pastor Eric © PUBLISHED JUNE 2018 PURPOSE CHURCH STUDENT MINISTRIES WWW.PURPOSECHURCH.COM/HSM V 02 SCRIPTURES TAKEN FROM THE HOLY BIBLE HIGH SCHOOL PASTOR | ERIC HOLMSTROM DFK PRODUCER | BRENDAN HIDALGO DFK THEME EDITOR | LAURA IRVINE DFK CONTENT EDITOR | ANDREW BERBERIAN Deeper Faith Kit: Matthew & Mark // Purpose Church // HSM DEEPER FAITH KIT PAGE TITLE 01 INTRODUCTION 02 COVENANT 05 SALVATION 06 BAPTISM 07 SCRIPTURE 08 PRAY 09 SING 10 COMMUNITY 11 SERVE 12 TITHE 15 DEVOTIONALS / READINGS 96 WHAT'S NEXT? Deeper Faith Kit: Matthew & Mark // Purpose Church // HSM ERIC HOLMSTROM BRENDAN HIDALGO HSM PASTOR // HSM PASTOR STUDENT LEADER // DFK EDITOR I will never forget when my We are so happy you picked up the relationship with Jesus took a huge Deeper Faith Kit: Matthew and turn and became something real Mark! I personally believe that this and life-changing. It wasn’t at a devotional will be the start to a camp, retreat, or an amazing youth lifelong journey that will lead to you group night—it was when I started being the change other people will the most adventurous, dangerous to benefit from! I was personally the enemy, and powerful habit of changed by the first Deeper Faith meeting God in His Word. Coming Kit and started making the Bible a face to face with Jesus through the priority because of it—I believe this Bible has transformed my life more could happen for you too! God is a than any other thing I’ve ever done. -

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

The All American Boy

The All American Boy His teeth I remember most about him. An absolutely perfect set kept totally visible through the mobile shutter of a mouth that rarely closed as he chewed gum and talked, simultaneously. A tricky manoeuvre which demanded great facial mobility. He was in every way the epitome of what the movies, and early TV had taught me to think of as the “All American Boy”. Six foot something, crew cut hair, big beaming smile, looked to be barely twenty. His mother must have been very proud of him! I was helping him to refuel the Neptune P2V on the plateau above Wilkes from numerous 44 gallon drums of ATK we had hauled to the “airstrip” on the Athey waggon behind a D4 driven by Max Berrigan. I think he was an aircraft mechanic. He and eight of his compatriots had just landed after a flight from Mirny, final stop McMurdo. Somehow almost all of the rest of his crew, and ours, had hopped into the weasels to go back to base for a party, leaving just a few of us “volunteers” to refuel. I remember too, feeling more than a little miffed when one of the first things he said after our self- introductions was “That was one hell of a rough landing strip you guys have - nearly as bad as Mirny”. Poor old Max had ploughed up and down with the D4 for hours knocking the tops of the Sastrugi and giving the “strip” as smooth a surface as he could. For there was not really a strip at Wilkes just a slightly flatter area of plateau defined by survey pegs. -

Alternative Spelling and Censorship: the Treatment of Profanities in Virtual Communities Laura-Gabrielle Goudet

Alternative spelling and censorship: the treatment of profanities in virtual communities Laura-Gabrielle Goudet To cite this version: Laura-Gabrielle Goudet. Alternative spelling and censorship: the treatment of profanities in virtual communities. Aspects of Linguistic Impoliteness, 2013. hal-02119772 HAL Id: hal-02119772 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02119772 Submitted on 4 May 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Alternative spelling and censorship: the treatment of profanities in virtual communities Laura-Gabrielle Goudet Université Paris 13, Sorbonne Paris Cité [email protected] [Author’s version of a paper published in Aspects of Linguistic Impoliteness (2013), Cambridge Scholars Publishing] Introduction Discourse on the internet is characterized by the paradoxical ability of users to write and communicate in alternative ways, with minimal supervision or external regularization—in most, not all communities—while new norms arise and are replaced according to users of virtual communities. On most websites, there is no regulating organ, except the Terms of Service that every registered user has to abide by. The standard version (used on websites like Facebook) includes a clause stipulating that the user should not: “use the Services […] to : upload, post, transmit, share, […] any User content [deemed] harmful, threatening, unlawful, defamatory, infringing, abusive, inflammatory, harassing, vulgar, obscene, […] hateful, or racially, ethnically or otherwise objectionable”. -

Domar Source: the Journal of Economic History, Vol

Economic History Association The Causes of Slavery or Serfdom: A Hypothesis Author(s): Evsey D. Domar Source: The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 30, No. 1, The Tasks of Economic History (Mar., 1970), pp. 18-32 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2116721 Accessed: 18-09-2015 10:24 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press and Economic History Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Economic History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 129.199.207.113 on Fri, 18 Sep 2015 10:24:51 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Causes of Slaveryor Serfdom: A Hypothesis I THE purposeof thispaper is to present,or morecorrectly, to revive,a hypothesisregarding the causes of agriculturalserf- dom or slavery (used here interchangeably).The hypothesiswas suggestedby Kliuchevsky'sdescription of the Russian experience in the sixteenthand seventeenthcenturies, but it aims at a wider applicability.' Accordingto Kliuchevsky,from about the second half of the fif- teenthcentury Russia was engaged in long hard wars against her westernand southernneighbors. -

Introduction: Memories of Slavery

INTRODUCTION MEMORIES OF SLAVERY On 27 April 1848, the Second Republic abolished slavery in its French overseas colonies thus ending three centuries of African slave trade and forced plantation labor. One hundred fifty years later the government of the Fifth Republic for the first time or- ganized extensive official celebrations to commemorate this historic event. The past was resurrected, invading the present with countless memories—though undoubtedly not the same for the French nation and for the formerly enslaved popula- tions in the overseas départements of Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana, and Reunion.1 The governmental commemorations of April 1998 were varied and all took place in France. President Jacques Chirac gave an opening speech, Prime Minister Lionel Jospin hon- ored the abolitionary fervor of the small village of Champag- ney, various ministers presented plaques commemorating important abolitionary figures and French Caribbean artists were invited for a variety of artistic performances. The over- seas domains also organized their own local commemorative functions including exhibitions, conferences, and theater pro- ductions as well as the inauguration of memorials. In Mar- tinique, for instance, scenes of the slave trade were reenacted with the arrival of a slave vessel, the unloading of slaves, and the reconstitution of a slave market. In Guadeloupe, a flame honoring the memory of the nèg mawon (fugitive slave) passed from township to township during the entire year preceding the 150th anniversary and was returned to its starting point amid celebrations, dances, and traditional music. 2 Catherine Reinhardt The most revealing aspects of the commemoration lie in the articles of major French and French Caribbean newspapers such as Le Monde, Libération, Le Figaro, and France-Antilles writ- ten for the occasion. -

The Role of Children's Racial Identity and Its Impact on Their

THE ROLE OF CHILDREN’S RACIAL IDENTITY AND ITS IMPACT ON THEIR SCIENCE EDUCATION by Lisa Mekia McDonald Dissertation Committee: Professor Felicia Moore Mensah, Sponsor Professor Denise Mahfood Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date: ___________________________________February 12, 2020 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2020 ABSTRACT THE ROLE OF CHILDREN’S RACIAL IDENTITY AND ITS IMPACT ON THEIR SCIENCE EDUCATION Lisa Mekia McDonald Racial identity plays an important role in the development of children’s narratives. In the structure of the classroom there is a disconnect for students between home and school. The structure of the classroom consists of the social relationships that children have with their peers and teachers. The structure of the classroom also includes how the classroom is set up for learning, such as the curriculum. Racial identity is also a valuable aspect in the construction of knowledge as children learn science. Racial identity is not often addressed with young children and science. Young children need to be able to see themselves in science regardless of their own race or ethnicity. Critical race theory (CRT) was used to examine and situate the context of race with children’s identity. Sociocultural theory was used to describe their process of learning. The participants of this study included 10 children in grades 3 through 5 who attended a diverse urban school located in New York City and their parents (10 parents). A qualitative approach was used to allow both children and parents to share their perspectives on their experience with science and difficult topics that pertain to race and/or skin color. -

From Theory to Practice in a Critical Race Pedagogy Classroom Van T

i.e.: inquiry in education Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 3 2017 In Real Time: From Theory to Practice in a Critical Race Pedagogy Classroom Van T. Lac University of Texas-San Antonio, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nl.edu/ie Recommended Citation Lac, Van T.. (2017). In Real Time: From Theory to Practice in a Critical Race Pedagogy Classroom. i.e.: inquiry in education: Vol. 9: Iss. 1, Article 3. Retrieved from: http://digitalcommons.nl.edu/ie/vol9/iss1/3 Copyright © 2017 by the author(s) i.e.: inquiry in education is published by the Center for Practitioner Research at the National College of Education, National-Louis University, Chicago, IL. Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank the following individuals for offering me critical feedback on this manuscript: Kim Bancroft, Gwen Baxley, Margarita Bianco, Carolyn Kelley, Andy Hatcher, and Pete Miller. This article is available in i.e.: inquiry in education: http://digitalcommons.nl.edu/ie/vol9/iss1/3 Lac: In Real Time In Real Time From Theory to Practice in a Critical Race Pedagogy Classroom Van T. Lac University of Texas-San Antonio, San Antonio, USA Introduction I enter this teacher action research project with an interest in studying how I, as a high school teacher, developed a critical race pedagogy (CRP) curriculum for students in an out-of-school context. My intrigue with race started at an early age growing up in Oakland, California, where my classmates were primarily of African American, Central American, and Southeast Asian descent. As a Southeast Asian student in Oakland schools, even with 100% students of color in my classes, my teachers in school rarely talked about race or racism. -

C.S. Lewis's Humble and Thoughtful Gift of Letter Writing

KNOWING . OING &DC S L EWI S I N S TITUTE Fall 2013 A Teaching Quarterly for Discipleship of Heart and Mind C.S. Lewis’s Humble and Thoughtful Gift of Letter Writing by Joel S. Woodruff, Ed.D. Vice President of Discipleship and Outreach, C.S. Lewis Institute s it a sin to love Aslan, the lion of Narnia, Recalling your tears, I long to see you, so that more than Jesus? This was the concern ex- I may be filled with joy” (2 Tim. 1:2–4 NIV). Ipressed by a nine-year-old American to his The letters of Paul, Peter, John, James, and Jude mother after reading The Chronicles of Narnia. that fill our New Testament give witness to the IN THIS ISSUE How does a mother respond to a question like power of letters to be used by God to disciple that? In this case, she turned straight to the au- and nourish followers of Jesus. While the let- 2 Notes from thor of Narnia, C.S. Lewis, by writing him a let- ters of C.S. Lewis certainly cannot be compared the President ter. At the time, Lewis was receiving hundreds in inspiration and authority to the canon of the by Kerry Knott of letters every year from fans. Surely a busy Holy Scriptures, it is clear that letter writing is scholar, writer, and Christian apologist of inter- a gift and ministry that when developed and 3 Ambassadors at national fame wouldn’t have the time to deal shared with others can still influence lives for the Office by Jeff with this query from a child. -

CSU Chancellor to Retire in 2020 by Brendan Cross STAFF WRITER

Tuesday, Volume 153 Oct. 29, 2019 No. 28 SERVING SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 WWW.SJSUNEWS.COM/SPARTAN_DAILY Opinion A&E Sports The sporting world Kanye blends rap Men’s soccer needs to move away and gospel in highly team wins with from racism anticipated album late goals Page 3 Page 4 Page 6 CSU Chancellor to retire in 2020 By Brendan Cross STAFF WRITER California State University The CSU is deeply Chancellor Timothy White woven into the fabric announced Oct. 22 his intent to retire after the end of the 2019-20 of California, having academic year. created opportunities White, who has served as chancellor since 2012, oversees for so many people more than 480,000 students, who now play critical 50,000 faculty and staff members and 23 campuses, including roles in our economic, San Jose State. social and political life. “The CSU is deeply woven into the fabric Timothy White of California, California State University Chancellor having created opportunities for By 2019, the freshman four- so many people year and six-year rates went up who now play by 8 percentage points and 5 WHITE critical roles in percentage points, respectively. our economic, The transfer graduation rates rose social and by 9 percentage points for two-year political life,” White said in a news transfers and 4 percentage points MAURICIO LA PLANTE | SPARTAN DAILY release. “It has been my great honor for four-years. A San Jose Police offi cer secures the perimeter of the crime scene by parking a vehicle on Fifth and San Fernando Saturday night. -

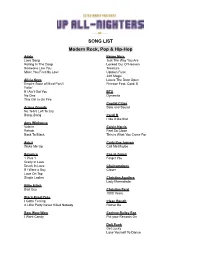

Band Song-List

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat.