Andrea Yates: a Continuing Story About Insanity Deborah W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Media Coverage of Domestic Violence Fatalities

News Media Coverage of Domestic Violence Fatalities National Domestic Violence Fatality Review Initiative Delray Beach, FL September 20, 2004 Mike Brigner, J.D. [email protected] Author, Ohio Domestic Violence Benchbook for Judges Former Ohio Domestic Relations Judge Some Statistical Issues A Boston Surprise In one recent year, Boston homicide detectives opened 150 case files That would be an all-time record high for murders in that city BUT: It turned out the city did not actually have a record number of homicides that year WHY? 3 A Boston Surprise In 82 of those 150 cases the victim did not die as originally expected Boston’s medical care system saved over half of potential homicide victims Those 82 cases became aggravated assault files, instead of homicide files Many victims are alive today who would have been a death statistic 25 years ago 4 What Have We Accomplished? DOJ study found that since 1976, the number of women killed by intimate partners has dropped slightly From about 1,600 a year then, To about 1,300 a year now That’s about a 19% decline in fatalities for battered women 5 Maybe, The Answer is Not Much So, if the medical community is arguably saving 50% of battered women who would have died a quarter century ago And women’s death statistics have fallen by only 19% Two logical conclusions: 1. Serious domestic violence incidents are actually increasing 2. The justice system has had no impact upon domestic violence and possibly has contributed to its increase 6 Florida Governor’s Task Force on Domestic -

MISSIONS in EASTERN EUROPE by Stanis Aw Wypych, C.M. the First

MISSIONS IN EASTERN EUROPE by Stanis_aw Wypych, C.M. The first purpose of this article is to describe the pastoral effort of the ConfReres working in three countries which have recently gained independence as a consequence of the collapse of the former Soviet Empire. These are Belorussia, The Ukraine and Lithuania. The selection has been determined by a desire to concentrate on countries in which the congregation originally began its labours in the 17th or 18th century. In the concluding section consideration will also be given to the enormous scope for pastoral opportunity currently developing in Russia. I BELORUSSIA 1. An historical background: Five confreres from the Polish province are currently working in Belorussia, however it is good to remember that the community's presence remained uninterrupted even during the Second World War. Fr. Michael WORONIECKI and his brother Ludovico who died only a few years ago remained all this time working in Belorussia. Father Michael Woroniecki was born in Wilejka Mala near Vilnius in 1908. He entered the congregation in 1927 and was ordained in 1935. He ministered briefly for two years in central Poland before returning East. He first worked in Lwow(Lvov) in the Ukraine from 1937 to 1945. After the War he moved to Lyskow in Belorussia until 1949 when he was arrested and sentenced to prison for 25 years. His sentence included several years forced labour in a frozen metal ore mine in Siberia. Upon his release he returned to the faithful of Belorussia ministering in Rozana until 1990 in which year he was appointed spiritual director of the seminary at Grodno. -

Yates Was Insane When Children Drowned, Jury Finds (Update2) Page 1 of 2 Bloomberg Printer-Friendly Page 7/28/2006

Bloomberg Printer-Friendly Page Page 1 of 2 Yates Was Insane When Children Drowned, Jury Finds (Update2) July 26 (Bloomberg) -- Andrea Yates, the Texas mother accused of drowning her five children in a bathtub in 2001, was found innocent by reason of insanity after a retrial. The jury, selected after an appeals court overturned a 2002 guilty verdict, accepted Yates's plea of not guilty based on the argument that she didn't know it was wrong to kill the children at the time. Yates, 42, will be sent to a mental institution, though it hasn't been determined where. According to Texas law, defendants can be declared not guilty by reason of insanity if it is determined that they were unaware that their actions were wrong at the time they committed the crime. When Yates was first tried in 2002, she also confessed to the killings and pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. ``The jury was able to see past what happened and look at why it happened,'' Rusty Yates, Andrea Yates's former husband, said during a press conference after the verdict. The couple divorced last year. Yates, who had a history of postpartum depression, said she drowned her children one by one and then dialed 911 to request police assistance. When officers arrived, Yates led them into a bedroom where 6- month-old Mary, sons Luke, 2; Paul, 3; and John, 5, lay on a bed, covered with a sheet. The oldest, Noah, 7, was found dead in the bathtub, police said. Postpartum Depression Yates will probably remain in a mental institution for life, said Charles Ewing, a forensic psychologist, professor of law at Buffalo Law School and author of books including ``Battered Women Who Kill'' and ``Fatal Families: The Dynamics of Intrafamilial Homicide.'' ``Theoretically, she's eligible for release when she's no longer mentally ill and dangerous,'' Ewing said. -

Janet Warren's CV

27-CV-15-20713 CURRICULUM VITAE JANET I. WARREN Janet I. Warren, DSW, LCSW The Institute of Law, Psychiatry and Public Policy P.O. Box 800660 UVA Health System University of Virginia Charlottesville, Virginia 229008-0660 (434) 924-8305 [email protected] FACULTY AND RESEARCH APPOINTMENTS 2002 - present Professor of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 2000 - present Associate, Park Dietz and Associates, Newport Beach, California 1996 - present University of Virginia Liaison, FBI Behavioral Sciences Unit, Quantico, Virginia 2000 - 2010 Associate Director, Institute of Law, Psychiatry and Public Policy, University of Virginia 1992 - 2002 Associate Professor of Clinical Psychiatric Medicine, General Medical Faculty, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 1991 - 1992 Assistant Professor of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry, General Medical Faculty, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 1985 - 1991 Assistant Professor, Division of Medical Center Social Work and Department of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry, General Medical Faculty, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 1981 - 1985 Instructor, General Medical Faculty, Division of Medical Center Social Work and Department of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia ADVISORY POSITIONS 1990 - 1991 Ritualistic Crime Task Force, Virginia State Crime Commission, Commonwealth of Virginia 1996-1997 Megan’s Law Crime Task Force, Virginia State Crime Commission, Commonwealth -

Esperanza Mas Alla Del Infierno

Lo que otros están diciendo... “El magnífico amor y sabiduría de Dios no ha sido escrito con tanta claridad desde el tiempo de los patriarcas. Yo aplaudo a Gerry Beauchemin por producir este importante libro. ¡Lo he estado esperando por 25 años!” Michael Wm. Gross, D.D., Th.D., Ph.D., Maryland “Todos deberían leer y estudiar Esperanza Más Allá del Infierno, un libro de esperanza. Léalo, entiéndalo y comparta el mensaje con otros.” Harold Lovelace, M.Th, D.D. Autor de Read and Search God’s Plan, AL “Con un gran discernimiento espiritual y un corazón en sintonía con el amor transformador de Dios, Gerry Beauchemin ha escrito un libro que, si usted lo permite, inspirará amor, paz, gozo, y esperanza – todo el fruto del Espíritu – en su corazón. Thomas Talbott, Profesor Emérito, Willamette University, Oregon Autor de The Inescapable Love of God “Aprendí, apoyé, y enseñé por primera vez las verdades presentadas en este libro hace más de 40 años. Esperanza Más Allá del Infierno encapsula estas verdades mejor que cualquier otra cosa que haya leído. Bill Boylan, Ph.D., Autor, Orador, South Dakota “Este es un excelente libro. Muchos de los que asisten a las iglesias de nuestros días harían bien en leer Esperanza Más Allá del Infierno y estudiar y pensar por sí mismos”. Bob Evely, M.Div., Asbury Theological Seminary, Autor de At the End of the Ages, Kentucky Esperanza Más Allá del Infierno contesta las preguntas que hemos temido hacer acerca del amor infalible e inagotable paciencia de Dios. Pastor Ivan A. Rogers, Ex-Presidente del Colegio Bíblico, Autor de Judas Iscariot: Revisited and Restored, Iowa “Como instructor de Historia de la Iglesia, Esperanza Más Allá del Infierno es uno de los estudios más balanceados disponibles en los juicios correctivos de Dios y la gran verdad de la restauración de todas las cosas en Cristo. -

All-Academic Release November 25, 2015 News Release for Immediate Release Nick Kornder • Asst

ALL-ACADEMIC RELEASE November 25, 2015 NEWS RELEASE www.northernsun.org For Immediate Release Nick Kornder • Asst. Commissioner for Media Relations • 2999 County Road 42 West • Burnsville, Minn. 55306 • P: 651.288.4017 • [email protected] 2015 NSIC Fall All-Academic Teams Announced WOMEN’S CROSS COUNTRY (77) Burnsville, Minn. — The Northern Sun Intercollegiate Conference announced that Leah Seivert So. Augustana Sibley, Iowa 638 student-athletes have earned NSIC All-Academic Teams honors for the 2015 Avery Selberg So. Augustana Moorhead, Minn. Fall athletic season. To be eligible for this honor, the student-athlete must be a Annie Kruse So. Augustana Yankton, S.D. member of the varsity traveling team and have a cumulative grade point average Jolynne Denman Sr. Bemidji State Esko, Minn. of 3.20 or higher. Furthermore, the athlete must have reached sophomore athletic Jordan Gray So. Concordia-St. Paul Crystal, Minn. and academic standing at her/his institution (true freshmen, red-shirt freshmen and Erin Spatenka Jr. Concordia-St. Paul Owatonna, Minn. ineligible athletic transfers are not eligible) and must have completed at least one Maggie Marcus Sr. Concordia-St. Paul Hutchinson, Minn. full academic year at that institution. Jessica Carlson Jr. University of Mary Grand Forks, N.D. Victoria Castillo Jr. University of Mary Austin, Texas MEN’S CROSS COUNTRY (47) Katelynn Engh Jr. University of Mary Maddock, N.D. Adam Kost So. Augustana Sioux Falls, S.D. Jessica Nehl So. University of Mary Watauga, S.D. Keegan Carda Jr. Augustana Sioux Falls, S.D. Kennedy Robbins Jr. University of Mary Billings, Mont. Glen Ellingson Jr. -

Midwestern Journal of Theology

MIDWESTERN JOURNAL OF THEOLOGY Volume 4 Fall 2005 No. 1 CONTENTS Editorial 2 Articles on Nehemiah: A Theological Primer for Nehemiah Mervin Breneman 3 A Teaching Outline for Nehemiah Stephen J. Andrews 18 An Annotated Bibliography Stephenie Long & for Nehemiah Andrew McClurg 27 Preaching from Nehemiah Albert F. Bean 34 Thanksgiving and Prayer to God: A Sermon on Nehemiah 11:17 by Scottish Baptist Preacher, Peter Grant of the Songs Terry L. Wilder 47 Special Report: What’s Going On in Salt Lake City? R. Philip Roberts 51 Book Reviews 57 Book Review Index 91 List of Publishers 93 Books Received 94 2 Midwestern Journal of Theology Editorial This issue is devoted to the Southern Baptist Convention’s January Bible Study book, Nehemiah. The articles contained in this volume are written to aid the busy pastor or teacher who will be leading in studies on this Old Testament book. Our guest contributor to this issue is Dr. Mervin Breneman, Professor of Old Testament at ESEPA Seminary in San Sebastián, Costa Rica. He is the author of numerous scholarly works, including a volume on Ezra and Nehemiah in the New American Commentary series. Breneman contributes to this journal a helpful article titled, “A Theological Primer for Nehemiah.” Other contributors of articles to this issue include: Dr. Stephen Andrews, Professor of OT and Hebrew at MBTS, who provides a teaching outline for Nehemiah. Stephenie Long and Andrew McClurg, MBTS teaching assistants, also supply an annotated bibliography for this OT book. Dr. Albert Bean, Professor of OT and Hebrew at MBTS, furnishes an article on preaching points from Nehemiah, and Dr. -

Re-Arranging Deck Chairs on the Titanic

\\server05\productn\H\HHL\5-1\HHL101.txt unknown Seq: 1 4-MAY-05 12:06 5 HOUS. J. HEALTH L. & POL’Y 1–73 1 R Copyright 2005 Jennifer S. Bard, Houston Journal of Health Law & Policy ISSN 1534-7907 RE-ARRANGING DECK CHAIRS ON THE TITANIC: WHY THE INCARCERATION OF INDIVIDUALS WITH SERIOUS MENTAL ILLNESS VIOLATES PUBLIC HEALTH, ETHICAL, AND CONSTITUTIONAL PRINCIPLES AND THEREFORE CANNOT BE MADE RIGHT BY PIECEMEAL CHANGES TO THE INSANITY DEFENSE Jennifer S. Bard* Anyone who has spent any time in the criminal justice system—as a defense lawyer, as a district attorney, or as a judge—knows that our treatment of criminal defendants with mental disabilities has been, forever, a scandal. Such defendants receive substandard counsel, are treated poorly in prison, receive disparately longer sentences, and are regularly coerced into confessing to crimes * Associate Professor of Law, Texas Tech University School of Law, Lubbock Texas; J.D., Yale Law School, 1987; M.P.H., University of Connecticut, 1997; A.B., Wellesley College, 1983. This work grew out of an invitation to give the second Nordenberg Lecture at the University of Pittsburgh Law School in October 2002, where I had the honor of Chancellor Nordenberg’s presence at the lecture. I very much appreciate the questions and comments following the lecture, which informed this article. Thank you also to Professor Elyn Saks, Orrin B. Evans Professor of Law, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of South- ern California Law School, who read a late draft and made many helpful comments; Donna Vickers of the University of Texas Medical Branch; and to my primary research assistant at Texas Tech Law School, Kristi Ward ’05, for her invaluable contributions to the project. -

Darin Routier Married

Darin routier married Continue Next up in the next countdown( countdownl) Next: NextVideo.title (nextVideo.description) Go to this video now Transcript for Darley Ruthier's ex-husband says she is innocent of the murders of her sons. But she looked into me, she saw DeVon. He looks like me and when I see her all Oslo pays. A lot of people think that because to get Charlie I don't believe under anymore, and that's far from the truth. Donnelly is the 100% innocent she's always been, and she's always going to have I didn't divorce Harley because I felt she was guilty. The variety is all right so I can move on. Hi dear. Some of my other children. This transcript was automatically generated and cannot be 100% accurate. American convicted death row killer Darley RoutierBornDarlie Lynn Peck (1970-01-04) January 4, 1970 (age 50)Altoona, Pennsylvania, U.S. Criminal StatusOn Death PenaltySpouse (s)Darin Routier (divorced)ChildrenDevon, Damon, and DrakeConviction (s)Capital Murder, one countCriminal penaltyDeathImprisoned at TheMountain View Unit, Texas Department of Criminal Justice , Darley Lynn Peck Routier (born January 4, 1970) is an American from Rowlett, Texas, who was convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of her five-year-old son Damon in 1996. She was also charged with capital murder in the death of her six-year-old son, Devon, who was killed at the same time as Damon. Until now, Ruthier has not been specifically tried for Devon's murder. Damon and Devon were stabbed with a large kitchen knife at Ruthier's home, while Ruthier was stabbed in the throat and arm. -

Trial Calendar: Boston, Massachusetts Date: May 21, 2007 PRETRIAL

Trial Calendar: Boston, Massachusetts Date: May 21, 2007 PRETRIAL MEMORANDUM FOR RESPONDENT NAME OF CASE: DOCKET NO. Rhiannon G. O'Donnabhain 6402-06 ATTORNEYS: Petitioner: Respondent: Karen L. Loewy Mary P. Hamilton (617) 426-1350 (617) 565-7915 Jennifer L. Levi John R. Mikalchus (617) 426-1350 (860) 290-4049 Bennett H. Klein Erika B. Cormier (617) 426-1350 (617) 565-5138 William E. Halmkin Molly H. Donohue (617) 338-2836 (617) 565-7828 David J. Nagle (617) 338-2873 Amy E. Sheridan (617) 338-2897 AMOUNTS IN DISPUTE: Year Deficiency 2001 $5,679* *As a result of concessions by the parties described below, the amount in dispute is less than the amount of the deficiency asserted in the notice of deficiency. STATUS OF CASE: Probable Settlement Probable Trial Definite Trial X_ Docket No. 6402-06 - 2 - CURRENT ESTIMATE OF TRIAL TIME: 40 hours MOTIONS RESPONDENT EXPECTS TO MAKE: Motions in Limine If necessary, to preclude Diane Ellaborn, LICSW, Alex Coleman, J.D., Ph.D., and Toby Meltzer, M.D., who have been identified by petitioner’s counsel as fact witnesses, from testifying in the capacity of expert witnesses. STATUS OF STIPULATION OF FACTS: Completed X In Process _ _ The Stipulation of Facts was submitted to the Court on June 15, 2007. A Supplemental Stipulation of Facts is expected to be submitted to the Court on July 3, 2007. ISSUE: Whether the costs of male to female sex reassignment surgery, feminizing hormone treatment, and other costs associated therewith including transportation and purported counseling are deductible medical expenses, as asserted by petitioner; or whether such expenses do not meet the requirements for deductible medical expenses under I.R.C. -

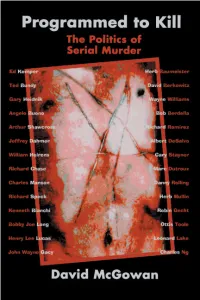

Programmed to Kill

PROGRAMMED TO KILL PROGRAMMED TO KILL The Politics of Serial Murder David McGowan iUniverse, Inc. New York Lincoln Shanghai Programmed to Kill The Politics of Serial Murder All Rights Reserved © 2004 by David McGowan No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. iUniverse, Inc. For information address: iUniverse, Inc. 2021 Pine Lake Road, Suite 100 Lincoln, NE 68512 www.iuniverse.com ISBN: 0-595-77446-6 Printed in the United States of America This book is for all the survivors. “This man, from the moment of conception, was programmed for murder.” —Attorney Ellis Rubin, speaking on behalf of serial killer Bobby Joe Long Contents Introduction: Mind Control 101 ................................................xi PART I: THE PEDOPHOCRACY Chapter 1 From Brussels… ......................................................3 Chapter 2 …to Washington ....................................................23 Chapter 3 Uncle Sam Wants Your Children ............................39 Chapter 4 McMolestation ......................................................46 Chapter 5 It Couldn’t Happen Here ........................................54 Chapter 6 Finders Keepers ......................................................59 PART II: THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT HENRY Chapter 7 Sympathy for the Devil ..........................................71 Chapter 8 Henry: -

Midwestern Journal of Theology Purchase for the Library of Anyone Who Desires Not Only to Be a Scholar of God’S Word, but Also a Proclaimer of That Word

57 Book Reviews Handbook on the Pentateuch. 2d ed. By Victor P. Hamilton. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2005. 468 pp. $32.99. Baker Academic has released a second edition of Victor P. Hamilton’s venerable Handbook on the Pentateuch. Hamilton, Professor of Bible and Theology at Asbury College for over thirty years, first published this work in 1982. Since that time the Handbook has been a popular text in undergraduate and graduate educational institutions around the world. The first edition has gone through twenty printings, has been translated into Russian, and has a Korean version in process also. Hamilton claims that this second edition is substantially revised. That is, it is not a mere reprint with minor typographic corrections. Hamilton first states that he has updated the bibliographies (13). Updating bibliographies and footnotes is a common feature of second editions. But is can said that Hamilton truly “substantially” updates the bibliographies in the Handbook. In the first edition, for example, the bibliography on Genesis 1-3 contains 70 entries classified in two sections. The same bibliography in the second edition contains four sections with over 200 citations. Hamilton updates all of the bibliographies in the same fashion offering a wealth of information to the student. Hamilton also rewrote many of the sections: “substantially adding to or revising what I wrote back in the early 1980s” (13). This is very important because Hamilton notes that the second edition has now been strengthened by his own “developed and developing thoughts on passages within the Pentateuch, informed and enriched greatly by interaction with scholarly colleagues in the Old Testament part of the biblical academy” (13).