Parking: Its Effect on the Form and the Experience of the City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Atlanta Preservation Center's

THE ATLANTA PRESERVATION CENTER’S Phoenix2017 Flies A CELEBRATION OF ATLANTA’S HISTORIC SITES FREE CITY-WIDE EVENTS PRESERVEATLANTA.COM Welcome to Phoenix Flies ust as the Grant Mansion, the home of the Atlanta Preservation Center, was being constructed in the mid-1850s, the idea of historic preservation in America was being formulated. It was the invention of women, specifically, the ladies who came J together to preserve George Washington’s Mount Vernon. The motives behind their efforts were rich and complicated and they sought nothing less than to exemplify American character and to illustrate a national identity. In the ensuing decades examples of historic preservation emerged along with the expanding roles for women in American life: The Ladies Hermitage Association in Nashville, Stratford in Virginia, the D.A.R., and the Colonial Dames all promoted preservation as a mission and as vehicles for teaching contributive citizenship. The 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition held in Piedmont Park here in Atlanta featured not only the first Pavilion in an international fair to be designed by a woman architect, but also a Colonial Kitchen and exhibits of historic artifacts as well as the promotion of education and the arts. Women were leaders in the nurture of the arts to enrich American culture. Here in Atlanta they were a force in the establishment of the Opera, Ballet, and Visual arts. Early efforts to preserve old Atlanta, such as the Leyden Columns and the Wren’s Nest were the initiatives of women. The Atlanta Preservation Center, founded in 1979, was championed by the Junior League and headed by Eileen Rhea Brown. -

Atlanta, GA 30309 11,520 SF of RETAIL AVAILABLE

Atlanta, GA 30309 11,520 SF OF RETAIL AVAILABLE LOCATED IN THE HEART OF 12TH AND MIDTOWN A premier apartment high rise building with a WELL POSITIONED RETAIL OPPORTUNITY Surrounded by Atlanta’s Highly affluent market, with Restaurant and retail vibrant commercial area median annual household opportunities available incomes over $74,801, and median net worth 330 Luxury apartment 596,000 SF Building $58 Million Project units. 476 parking spaces SITE PLAN - PHASE 4A / SUITE 3 / 1,861 SF* SITE PLAN 12th S TREET SUITERETAIL 1 RETAIL SUITERETAIL 3 RESIDENTIAL RETAIL RETAIL 1 2 3 LOBBY 4 5 2,423 SF 1,8611,861 SFSF SUITERETAIL 6A 3,6146 A SF Do Not Distrub Tenant E VENU RETAIL A 6 B SERVICE LOADING S C E N T DOCK SUITERETAIL 7 E 3,622 7 SF RETAIL PARKING CR COMPONENT N S I T E P L AN O F T H E RET AIL COMP ONENT ( P H ASE 4 A @ 77 12T H S TREE T ) COME JOIN THE AREA’S 1 2 TGREATH & MID OPERATORS:T O W N C 2013 THIS DRAWING IS THE PROPERTY OF RULE JOY TRAMMELL + RUBIO, LLC. ARCHITECTURE + INTERIOR DESIGN AND MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT WRITTEN CONSENT A TLANT A, GEOR G I A COMMISSI O N N O . 08-028.01 M A Y 28, 2 0 1 3 L:\06-040.01 12th & Midtown Master Plan\PRESENTATION\2011-03-08 Leasing Master Plan *All square footages are approximate until verified. THE MIDTOWN MARKET OVERVIEW A Mecca for INSPIRING THE CREATIVE CLASS and a Nexus for TECHNOLOGY + INNOVATION MORE THAN ONLY 3 BLOCKS AWAY FROM 3,000 EVENTS ANNUALLY PIEDMONT PARK • Atlanta Dogwood Festival, • Festival Peachtree Latino THAT BRING IN an arts and crafts fair • Music Midtown & • The finish line of the Peachtree Music Festival Peachtree Road Race • Atlanta Pride Festival & 6.5M VISITORS • Atlanta Arts Festival Out on Film 8 OF 10 ATLANTA’S “HEART OF THE ARTS”DISTRICT ATLANTA’S LARGEST LAW FIRMS • High Museum • ASO • Woodruff Arts Center • Atlanta Ballet 74% • MODA • Alliance Theater HOLD A BACHELORS DEGREE • SCAD Theater • Botanical Gardens SURROUNDED BY ATLANTA’S TOP EMPLOYERS R. -

REGIONAL RESOURCE PLAN Contents Executive Summary

REGIONAL RESOURCE PLAN Contents Executive Summary ................................................................5 Summary of Resources ...........................................................6 Regionally Important Resources Map ................................12 Introduction ...........................................................................13 Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value .................21 Areas of Historic and Cultural Value ..................................48 Areas of Scenic and Agricultural Value ..............................79 Appendix Cover Photo: Sope Creek Ruins - Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area/ Credit: ARC Tables Table 1: Regionally Important Resources Value Matrix ..19 Table 2: Regionally Important Resources Vulnerability Matrix ......................................................................................20 Table 3: Guidance for Appropriate Development Practices for Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value ...........46 Table 4: General Policies and Protection Measures for Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value ................47 Table 5: National Register of Historic Places Districts Listed by County ....................................................................54 Table 6: National Register of Historic Places Individually Listed by County ....................................................................57 Table 7: Guidance for Appropriate Development Practices for Areas of Historic and Cultural Value ............................77 Table 8: General Policies -

Raise the Curtain

JAN-FEB 2016 THEAtlanta OFFICIAL VISITORS GUIDE OF AtLANTA CoNVENTI ON &Now VISITORS BUREAU ATLANTA.NET RAISE THE CURTAIN THE NEW YEAR USHERS IN EXCITING NEW ADDITIONS TO SOME OF AtLANTA’S FAVORITE ATTRACTIONS INCLUDING THE WORLDS OF PUPPETRY MUSEUM AT CENTER FOR PUPPETRY ARTS. B ARGAIN BITES SEE PAGE 24 V ALENTINE’S DAY GIFT GUIDE SEE PAGE 32 SOP RTS CENTRAL SEE PAGE 36 ATLANTA’S MUST-SEA ATTRACTION. In 2015, Georgia Aquarium won the TripAdvisor Travelers’ Choice award as the #1 aquarium in the U.S. Don’t miss this amazing attraction while you’re here in Atlanta. For one low price, you’ll see all the exhibits and shows, and you’ll get a special discount when you book online. Plan your visit today at GeorgiaAquarium.org | 404.581.4000 | Georgia Aquarium is a not-for-profit organization, inspiring awareness and conservation of aquatic animals. F ATLANTA JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2016 O CONTENTS en’s museum DR D CHIL ENE OP E Y R NEWL THE 6 CALENDAR 36 SPORTS OF EVENTS SPORTS CENTRAL 14 Our hottest picks for Start the year with NASCAR, January and February’s basketball and more. what’S new events 38 ARC AROUND 11 INSIDER INFO THE PARK AT our Tips, conventions, discounts Centennial Olympic Park on tickets and visitor anchors a walkable ring of ATTRACTIONS information booth locations. some of the city’s best- It’s all here. known attractions. Think you’ve already seen most of the city’s top visitor 12 NEIGHBORHOODS 39 RESOURCE Explore our neighborhoods GUIDE venues? Update your bucket and find the perfect fit for Attractions, restaurants, list with these new and improved your interests, plus special venues, services and events in each ’hood. -

Midtown Atlanta’S Innovation District 100% Leased Long-Term to At&T

TWO CLASS A OFFICE BUILDINGS IN MIDTOWN ATLANTA’S INNOVATION DISTRICT 100% LEASED LONG-TERM TO AT&T MIDTOWN ONE AND TWO 754 PEACHTREE STREET & 725 WEST PEACHTREE STREET ATLANTA, GEORGIA Executive Summary 285 285 23 41 19 85 19 41 23 285 141 407 85 285 19 13 29 75 78 6 78 78 41 278 MIDTOWN19 13 278 ONE & TWO 23 29 278 MIDTOWN TWO 280 PARKING 285 70 6 ATLANTA 23 29 278 20 20 278 285 280 20 20 MIDTOWN ONE 280 6 407 278 70 85 42 23 29 19 20 278 6 20 166 294 Luxury residential units 166 285 (Under Construction) 155 Not included in offering 70 75 29 85 6 19 23 139 19 29 285 Hartsfield - Jackson Atlanta International Airport 85 407 2 Midtown One and Two Midtown PARKING MIDTOWN TWO MIDTOWN ONE CORE INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS • Best-in-class, trophy quality, 794,110 RSF in two office buildings and a 2,459 space parking structure constructed in 2001 and 2002. • 100% leased to AT&T as part of its regional headquarters in Atlanta • Investment grade tenant with a market cap in excess of $174 billion • Triple-net lease structure with annual rent escalations. • Outstanding amenity base provided by its position within the “Midtown Mile,” home of the most dense concentration of cultural and retail amenities in all of Atlanta, as well as 4,100 hotel rooms and and a booming high-rise residential market. 3 • Adjacent to the North Avenue MARTA rail transit station. Executive Summary Executive • Outstanding accessibility provided by proximity to the Downtown Connector (I-85/I-75), which is accessible in less than 3 minutes. -

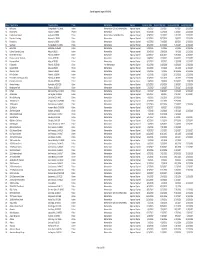

Project-Approval-Log-Condos.Pdf

Condo Approval Log as of 3‐16‐19 State Project Name Project Location Phase Warrantable Decision Expiration Date HOA Cert Exp Date Insurance Exp Date Budget Exp Date AL Bella Luna Orange Beach, AL. 36561 Entire Warrantable ‐ O/O or 2nd Home Only Approval Expired 3/5/2017 2/27/2017 4/7/2017 12/31/2016 AL Brown Crest Auburn, AL 36832 Phase 1 Warrantable Approval Expired 9/24/2016 11/2/2016 2/28/2017 12/31/2016 AL Creekside of Auburn AL, Auburn 36830 Entire Warrantable ‐ Freddie Mac Only Approval Expired 3/28/2017 3/13/2017 11/1/2017 12/31/2017 AL Donahue Crossing Auburn, AL. 36830 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 11/13/2016 10/27/2016 7/4/2017 12/31/2016 AL Residences Auburn, AL 36830 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 9/15/2016 7/14/2016 8/6/2016 12/31/2016 AL Seachase Orange Beach, AL 36561 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 12/1/2016 11/14/2016 5/23/2017 12/31/2016 AZ Bella Vista Scottsdale, AZ 85260 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 9/10/2015 9/3/2015 5/9/2016 12/31/2015 AZ Colonial Grande Casitas Mesa, AZ 85211 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 3/14/2018 2/28/2018 7/6/2018 12/31/2018 AZ Desert Breeze Villas Phoenix, AZ 85037 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 11/25/2017 11/21/2017 6/25/2018 12/31/2017 AZ Discovery at the Orchards Peoria, AZ 85381 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 8/8/2017 7/19/2017 8/24/2017 12/31/2017 AZ Eastwood Park Mesa, AZ 85203 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 9/12/2017 9/7/2017 1/30/2018 12/31/2017 AZ El Segundo Phoenix, AZ 85008 Entire Non‐Warrantable Approval Expired 9/21/2018 8/28/2018 11/8/2018 12/31/2018 AZ Leisure World Mesa, AZ 85206 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 3/11/2018 3/4/2018 1/1/2018 12/31/2017 AZ Mountain Park Phoenix AZ 85020 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 7/13/2015 7/2/2015 11/15/2015 12/31/2015 AZ Palm Gardens Phoenix, AZ 85041 Entire Warrantable Approval Expired 7/11/2016 7/5/2016 11/23/2016 12/31/2016 AZ Pointe Resort @ Tapatio Cliffs Phoenix, AZ. -

12 & MIDTOWN to SHAPE MIDTOWN's FUTURE Daniel

12th & MIDTOWN TO SHAPE MIDTOWN’S FUTURE Daniel Corporation, Selig Enterprises and the Canyon-Johnson Urban Fund Partner on Atlanta’s Midtown Mile ATLANTA (November 10, 2006) — Daniel Corporation, Selig Enterprises and the Canyon-Johnson Urban Fund (CJUF) today announce plans for 12th & Midtown. Spanning three city blocks, 12th & Midtown is a 2.5-million-square-foot mixed-use development featuring Class A office towers, luxury hotels, premium residences and flagship retail. With this development, the team becomes the largest single contributor to Atlanta’s Midtown Mile. “The City of Atlanta is dedicated to improving the Atlanta experience for residents and visitors alike – and 12th & Midtown is a giant step forward in accomplishing this goal,” said Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin. “We are thrilled that Daniel Corporation and Selig Enterprises have teamed up with Earvin “Magic” Johnson and the Canyon-Johnson Urban Fund again. As a team they are committed to providing an improved quality of life for Atlantans while continuing to contribute to the economic growth for the state of Georgia.” The partners have strategically assembled three city blocks at the intersection of Peachtree and 12th streets to create a robust master-plan in the heart of Midtown, which will feature more than 1.2 million square feet of Class A office space, over 500 hotel rooms, more than 600 residences and up to 150,000 square feet of flagship retail space. The development is designed to enhance the pedestrian streetscape and to maximize views of the Atlanta skyline and Piedmont Park. The street level has been carefully designed to accommodate the demands of world-renowned flagship retailers, including 35-foot-high storefronts and super-graphic displays, for a commanding presence along Atlanta’s Midtown Mile. -

Margaret Fletcher [email protected]

Margaret Fletcher [email protected] www.margaretfletcher.com Education 1995–1997 Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Cambridge, Massachusetts Master of Architecture, June 1997 1988–1993 Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama Bachelor of Architecture, June 1993 Magna Cum Laude 1987–1988 Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida General Studies Teaching Experience 2011–present Auburn University School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture Auburn, Alabama Associate Professor of Architecture Program of Architecture Associate Chair ARCH4020: Design Studio Fourth Year ARCH3410: Advanced Portfolio Design ARCH3410, Rome Program: Advanced Visual Communications Workshop ARCH1010, ARCH1020: First Year Design Studio—Architecture ARCH1060: Visual Communications ARCH1420: Introduction to Digital Media (Visual Communications II) ARCH5100: Teaching Methods 2004, 2008 Adjunct Professor of Architecture Seminar WORD | IMAGE, visual representation of architectural ideas First Year Design Studio—Architecture 2004, 2006 Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia Lecturer in Architecture Studio Instructor for Common First Year—Architecture, Industrial Design and Building Construction 1996–1998 Boston Architectural College Boston, Massachusetts Architecture Studio Instructor—Foundation Studios 1995–present Visiting Design Critic Auburn University, Boston Architectural College, Georgia Institute of Technology, Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Northeastern University, Oklahoma State University, Rhode Island School -

As of September 2018 TECH PARKWAY CHERRY ST

INVESTMENT MAP As of September 2018 TECH PARKWAY CHERRY ST ON LE WALLACE ST DE PONCE DE LEON AVE E LEON CE A B C D E F G CE D H I J PON K STATE ST N MARIETTA ST PO North Ave. NORTH AVE NORTH AVE NORTH AVE N INVESTMENT INDEX 1 NORTH AVE 9 D 1 NORTHSIDE DR N A L T R U RECENTLY COMPLETED UNDER CONSTRUCTION PLANNED PROJECT O C W E BOULEVARD PL NORTH AVE LINDEN WAY WILLOW ST SONO 37 LINDEN AVE (SOUTH OF NORTH) 1. 10 Park Place (F-8) 36. Healey Building / 75 23 64 S MORGAN ST Renovations (E-8) MERRITTS AVE MERRITTS AVE 2. 120 Piedmont PIEDMONT AVE 85 WEST PEACHTREE ST Student Housing (H-7) 37. Herdon Homes 2 NORTHYARDS BLVD 24 RENAISSANCE PKWY 2 Redevelopment (A-2) SPRING ST MARIETTA ST BALTIMORE PL 3. 143 Alabama / NORTHSIDE DR Constitution Building (E-9) 38. Herman J. Russell 54 Renaissance KENNEDY ST PINE ST Park Center for Innovation and PINE ST 4. 99-125 Ted Turner Entrepreneurship / Renovation PINE STREET Drive (C-9) (A-11) PINE ST RANKIN ST 5. Atlanta Capital 39. Home Depot Backyard LUCKIE ST ANGIER AVE GRAY ST Center Hotel (E-10) (B-7) HUNNICUT ST 60 ARNOLD ST JOHN ST Civic COURTLAND ST 3 Cen ter 3 6. Atlanta-FultonANGIER AVE 40. Hurt Building / Central Library (F-7) Renovations (F-8) PARKER ST PARKER ST 17 MCAFEE ST LOVEJOY ST 7. Auburn Apartments 41. Hyatt Place Hotel (C-5) CENTENNIAL OLYMPIC PARK DR CURRIER ST MARIETTA ST MILLS ST PARKWAY DR (H-8) NORTHSIDE DR SPRING ST ANGIER PL BOULEVARD 42. -

Downtown Atlanta Available Sites

Downtown Atlanta Available Sites CURRENTLY ON THE MARKET South Downtown 1. Ted Turner Drive at Whitehall Street – Artisan Yards Atlanta, GA 30303 Multi-parcel assemblage under single ownership 9.86 AC (429,502 SF) lot Contact: Bruce Gallman at [email protected] 2. 175-181 Peachtree St SW - Vacant Land/Parking Lot Land of 0.25 AC. Site adjoins Garnett MARTA Station, for sale, lease, or will develop, key corner with 110" frontage on Peachtree St. and 100' frontage on Trinity Ave. For sale at $2,240,000 ($8,712,563/AC) John Paris, Paris Properties at (404) 763-4411 and [email protected] 3. Broad St/Mitchell Street Assemblage 111 Broad Street, SW, Atlanta, GA 30303 (3,648 s.f.) 115 Broad Street, SW, Atlanta, GA 30303 (3,072 s.f.) 185 Mitchell Street, SW, Atlanta, GA 30303 (5,228 s.f.) Parking Lot on Mitchell Street, SW - Between 185 & 191 Mitchell Street 191 Mitchell Street, SW, Atlanta, GA. 30303 (2,645 s.f.) For sale at $3.6 million Contact Dave Aynes, Broker / Investor, (404) 348-4448 X2 (p) or [email protected] 4. 207-211 Peachtree St Atlanta, GA For Sale at $1,050,000 ($35.02/SF) 29,986 SF Retail Freestanding Building Built in 1915 Contact: Herbert Greene, Jr. (404) 589-3599 (p) or [email protected] 5. 196 Peachtree Street Atlanta, GA 19,471 SF Retail Storefront Retail/Office Building Built in 1970 For Sale at $5 million ($256.79/SF) Contact: Herbert Greene, Jr. (404) 589-3599 (p) or [email protected] 6. -

Atlanta, GA 30309 11,520 SF of RETAIL AVAILABLE

Atlanta, GA 30309 11,520 SF OF RETAIL AVAILABLE L O C A T E D IN THE HEART O F 12TH AND M I D T O W N A premier apartment high rise building with aWELL POSITIONED RETAIL OPPORTUNITY Surrounded by Atlanta’s Highly affluent market, with Restaurant and retail vibrant commercial area median annual household opportunities available incomes over $74,801, and median net worth 330 Luxury apartment 596,000 SF Building $58 Million Project units. 476 parking spaces SITE PLAN RESIDENTIA SUITERETAIL1 RETAIL SUITERETAIL 3 RETAIL RETAIL 1 2 3 L LOBBY 4 5 2,423 SF 1,8611,861 SFSF SUITERETAIL6A AT 3,6146A SF LEASE RETAIL 6B SUITE 7 SERVICE 3,622 SF LOADING DOCK RETAIL AT 7 LEASE RETAIL PARKING COMPONENT COME JOIN THE AREA’S GREAT OPERATORS: T H E MIDTOWN MARKET O VER VIEW A Mecca for INSPIRING THE CREATIVE CLASS and aNexus for TECHNOLOGY + INNOVATION MORE THAN O N L Y 3 B L OCK S A W A Y FROM 3,000 EVENTS ANNUALLY PIEDMONT PARK • Atlanta Dogwood Festival, THAT BRING IN • Festival Peachtree Latino an arts and crafts fair • Music Midtown & • The finish line of the Peachtree Music Festival Peachtree Road Race • Atlanta Pride Festival & 6.5M VISITORS • Atlanta Arts Festival Out on Film 8 OF 10 ATLANTA’S “HEART OF THE ARTS”DISTRICT ATLANTA’S LARGEST LAW FIRMS • High Museum • ASO • Woodruff Arts Center • Atlanta Ballet 74% • MODA • Alliance Theater HOLD A BACHELORS DEGREE • SCAD Theater • Botanical Gardens SURROUNDED B Y A TLANT A ’ S T O P EMPL O YERS R. -

Education 1995–1997 Harvard University

Margaret Fletcher Margaret Fletcher 410 Dudley Hall Auburn University, Alabama 36849 334.844.8659 [email protected] Education 1995–1997 Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Cambridge, Massachusetts Master of Architecture, June 1997 1988–1993 Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama Bachelor of Architecture, June 1993 Magna Cum Laude 1987–1988 Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida General Studies Teaching Experience 2011–present Auburn University School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture Auburn, Alabama Associate Professor of Architecture ARCH1010, ARCH1020: First Year Design Studio—Architecture ARCH1060: Visual Communications ARCH1420: Introduction to Digital Media (Visual Communications II) ARCH5100: Teaching Methods 2004, 2008 Adjunct Professor of Architecture Seminar WORD | IMAGE, visual representation of architectural ideas First Year Design Studio—Architecture 2004, 2006 Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia Lecturer in Architecture Studio Instructor for Common First Year—Architecture, Industrial Design and Building Construction 1996–1998 Boston Architectural College Boston, Massachusetts Architecture Studio Instructor—Foundation Studios 1995–present Visiting Design Critic Auburn University, Boston Architectural College, Georgia Institute of Technology, Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Northeastern 4 Dossier Support Document—CV University, Oklahoma State University, Rhode Island School of Design, Southern Polytechnic State University, University of Arkansas, Wentworth Institute