Poster Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arlington Springs Man”

“Arlington Springs Man” Resource Summary: Study guide questions for viewing the video with answer key, vocabulary worksheet relating to Santa Rosa Island, additional articles about the island and Arlington Springs Man, maps of the current and prehistoric island. Subject Areas: science, human geography Grade Level Range: 5-10 Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.9-10.2 Write informative/explanatory texts, including the narration of historical events, scientific procedures/ experiments, or technical processes. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.WHST.9-10.2.D Use precise language and domain-specific vocabulary to manage the complexity of the topic and convey a style appropriate to the discipline and context as well as to the expertise of likely readers. Resource Provided By: Lucy Carleton, English/ELD, Carpinteria High School, Carpinteria Unified School District Resource Details: “Arlington Springs Man” Running time 9 minutes. Cast: Dr. Jon Erlandson, archaeologist, University of Oregon Dr. John Johnson, curator of anthropology, Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Don Morris, archaeologist Channel Islands national Park (retired) Phil Orr, (non speaking role) Curator of anthropology Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Study Guide “Arlington Springs Man” The West of the West 1. Define strata: 2. In what ways is Santa Rosa Island just like a layer cake? 3. Why is Santa Rosa Island such a perfect place for archaeologists and geologists to study? 4. What caused the formation of the prehistoric mega-island Santarosae (Santa Rosae) and which of the current Channel Islands were part of it? 5. How far can a modern-day elephant swim? What can you conclude about how mammoths arrived to the islands? 6. -

Contributions by Employer

2/4/2019 CONTRIBUTIONS FOR HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT HOME / CAMPAIGN FINANCE REPORTS AND DATA / PRESIDENTIAL REPORTS / 2008 APRIL MONTHLY / REPORT FOR C00431569 / CONTRIBUTIONS BY EMPLOYER CONTRIBUTIONS BY EMPLOYER HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT PO Box 101436 Arlington, Virginia 22210 FEC Committee ID #: C00431569 This report contains activity for a Primary Election Report type: April Monthly This Report is an Amendment Filed 05/22/2008 EMPLOYER SUM NO EMPLOYER WAS SUPPLIED 6,724,037.59 (N,P) ENERGY, INC. 800.00 (SELF) 500.00 (SELF) DOUGLASS & ASSOCI 200.00 - 175.00 1)SAN FRANCISCO PARATRAN 10.50 1-800-FLOWERS.COM 10.00 101 CASINO 187.65 115 R&P BEER 50.00 1199 NATIONAL BENEFIT FU 120.00 1199 SEIU 210.00 1199SEIU BENEFIT FUNDS 45.00 11I NETWORKS INC 500.00 11TH HOUR PRODUCTIONS, L 250.00 1291/2 JAZZ GRILLE 400.00 15 WEST REALTY ASSOCIATES 250.00 1730 CORP. 140.00 1800FLOWERS.COM 100.00 1ST FRANKLIN FINANCIAL 210.00 20 CENTURY FOX TELEVISIO 150.00 20TH CENTURY FOX 250.00 20TH CENTURY FOX FILM CO 50.00 20TH TELEVISION (FOX) 349.15 21ST CENTURY 100.00 24 SEVEN INC 500.00 24SEVEN INC 100.00 3 KIDS TICKETS INC 121.00 3 VILLAGE CENTRAL SCHOOL 250.00 3000BC 205.00 312 WEST 58TH CORP 2,000.00 321 MANAGEMENT 150.00 321 THEATRICAL MGT 100.00 http://docquery.fec.gov/pres/2008/M4/C00431569/A_EMPLOYER_C00431569.html 1/336 2/4/2019 CONTRIBUTIONS FOR HILLARY CLINTON FOR PRESIDENT 333 WEST END TENANTS COR 100.00 360 PICTURES 150.00 3B MANUFACTURING 70.00 3D INVESTMENTS 50.00 3D LEADERSHIP, LLC 50.00 3H TECHNOLOGY 100.00 3M 629.18 3M COMPANY 550.00 4-C (SOCIAL SERVICE AGEN 100.00 402EIGHT AVE CORP 2,500.00 47 PICTURES, INC. -

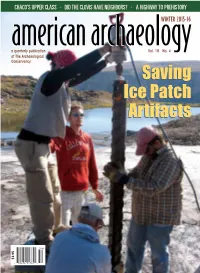

Saving Ice Patch Artifacts Saving Ice Patch Artifacts

CHACO’S UPPER CLASS • DID THE CLOVIS HAVE NEIGHBORS? • A HIGHWAY TO PREHISTORY american archaeologyWINTER 2015-16 americana quarterly publication archaeology Vol. 19 No. 4 of The Archaeological Conservancy SavingSaving IceIce PatchPatch ArtifactsArtifacts $3.95 american archaeologyWINTER 2015-16 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 19 No. 4 COVER FEATURE 12 ARCHAEOLOGY IN THE ICE PATCHES BY TAMARA STEWART Archaeologists are racing to preserve fragile artifacts that are exposed when ice patches melt. 19 THE ROAD TO PREHISTORY BY ELIZABETH LUNDAY A highway-expansion project in Texas led to the discovery of several ancient Caddo sites and raised issues about preservation. 26 CHACO’S UPPER CLASS EE L BY CHARLES C. POLING New research suggests an elite class emerged at RAIG C / Chaco Canyon much earlier than previously thought. AAR NST 32 DID THE CLOVIS PEOPLE HAVE NEIGHBORS? I 12 BY MARCIA HILL GOSSARD Discoveries from the Cooper’s Ferry site indicate that two different cultures inhabited North America 44 new acquisition roughly 13,000 years ago. CONSERVANCY ACQUIRES A PORTION OF MANZANARES PUEBLO IN NEW MEXICO 38 LIFE ON THE NORTHERN FRONTIER Manzanares is one of the sites included in the Galisteo BY WAYNE CURTIS Basin Archaeological Sites Protection Act. Researchers are trying to understand what life was like at an English settlement in southern Maine around 46 new acquisition the turn of the 18th century. DONATION OF TOWN SQUARE BANK MOUND UNITES LOCAL COMMUNITY Various people played a role in the Conservancy’s 19 acquisition of a prehistoric mound. 47 point acquisition A LONG TIME COMING The Conservancy waited for 20 years to acquire T the Dingfelder Circle. -

Charles Lindbergh's Contribution to Aerial Archaeology

THE FATES OF ANCIENT REMAINS • SUMMER TRAVEL • SPANISH-INDIGENOUS RELIGIOUS HARMONY american archaeologySUMMER 2017 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 21 No. 2 Charles Lindbergh’s Contribution To Aerial Archaeology $3.95 US/$5.95 CAN summer 2017 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 21 No. 2 COVER FEATURE 18 CHARLES LINDBERGH’S LITTLE-KNOWN PASSION BY TAMARA JAGER STEWART The famous aviator made important contributions to aerial archaeology. 12 COMITY IN THE CAVES BY JULIAN SMITH Sixteenth-century inscriptions found in caves on Mona Island in the Caribbean suggest that the Spanish respected the natives’ religious expressions. 26 A TOUR OF CIVIL WAR BATTLEFIELDS BY PAULA NEELY ON S These sites serve as a reminder of this crucial moment in America’s history. E SAM C LI A 35 CURING THE CURATION PROBLEM BY TOM KOPPEL The Sustainable Archaeology project in Ontario, Canada, endeavors to preserve and share the province’s cultural heritage. JAGO COOPER AND 12 41 THE FATES OF VERY ANCIENT REMAINS BY MIKE TONER Only a few sets of human remains over 8,000 years old have been discovered in America. What becomes of these remains can vary dramatically from one case to the next. 47 THE POINT-6 PROGRAM BEGINS 48 new acquisition THAT PLACE CALLED HOME OR Dahinda Meda protected Terrarium’s remarkable C E cultural resources for decades. Now the Y S Y Conservancy will continue his work. DD 26 BU 2 LAY OF THE LAND 3 LETTERS 50 FiELD NOTES 52 REVIEWS 54 EXPEDITIONS 5 EVENTS 7 IN THE NEWS COVER: In 1929, Charles and Anne Lindbergh photographed Pueblo • Humans In California 130,000 Years Ago? del Arroyo, a great house in Chaco Canyon. -

Shannon Walker (Ph.D.) NASA Astronaut

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas 77058 May 2021 Shannon Walker (Ph.D.) NASA Astronaut Summary: Shannon Walker was selected by NASA to be an astronaut in 2004. She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Physics, a Master of Science and a Doctorate of Philosophy in Space Physics from Rice University. Walker began her professional career at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in 1987 as a Robotics Flight Controller for the Space Shuttle Program. In 2010, she served as Flight Engineer for Expedition 24/25, a long-duration mission aboard the International Space Station that lasted 163 days. Walker most recently served as mission specialist on the on the Crew-1 SpaceX Crew Dragon, named Resilience, which landed May 2, 2021. She also served as Flight Engineer on the International Space Station for Expedition 64. Personal Data: Born June 4, 1965 in Houston, Texas. Married to astronaut Andy Thomas. Recreational interests include cooking, running, weight training, camping and travel. Her mother, Sherry Walker, resides in Houston, Texas. Her father, Robert Walker, is deceased. Education: Graduated from Westbury Senior High, Houston, Texas, in 1983; received a Bachelor of Arts degree in Physics from Rice University in 1987; received a Master of Science and a Doctorate of Philosophy in Space Physics from Rice University in 1992 and 1993, respectively. NASA Experience: Dr. Walker began her professional career with the Rockwell Space Operations Company at the Johnson Space Center in 1987 as a Robotics Flight Controller for the Space Shuttle Program. She worked Space Shuttle missions as a Flight Controller in the Mission Control Center, including STS-27, STS-32, STS-51, STS-56, STS-60, STS-61, and STS-66. -

Juan Manuel Rivera Acosta Phd Thesis

LEAVE US ALONE, WE DO NOT WANT YOUR HELP. LET US LIVE OUR LIVES; INDIGENOUS RESISTANCE AND ETHNOGENESIS IN NUEVA VIZCAYA (COLONIAL MEXICO) Juan Manuel Rivera Acosta A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2017 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11060 This item is protected by original copyright Leave us alone, we do not want your help. Let us live our lives; Indigenous resistance and ethnogenesis in Nueva Vizcaya (colonial Mexico) Juan Manuel Rivera Acosta This thesis is submitted in partial FulFilment For the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews October 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Juan Manuel Rivera Acosta, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 75,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in Social Anthropology and Amerindian Studies in September 2010; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2015. Date 29-10-2015 signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in Social Anthropology and Amerindian Studies in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Monterey Bay 99S Membership Meeting July 20, 2011

Monterey Bay 99s established August 14, 1965 Geneva Cranford 1923-2011 Our beloved Geneva, a charter member of the MB99s, flew to new horizons on July 25 at the age of 88. Above, Geneva completes a skydiving jump from 15,000 feet on her 80th birthday in a gold lamé jumpsuit she designed and made herself for the occasion. More photos on p. 4. August Chapter Meeting What’s Inside The August meeting will begin at 6pm on Wednes- Prop Wash / Current Membership 2 day, Aug. 17, in the EAA hangar at WVI. Fly-In MB99s Meeting Minutes / Section Mtg Info 3 Work Party & Pot Luck Dinner. Exit Hwy 1 at Remembering Geneva 4 Airport Blvd., go toward hills, turn left after 3rd stop- Fly-In Info / Member Activities 5 light (Hangar Way) onto Aviation Way, proceed past1 International Highlights by Mary Doherty 6&7 WVI terminal and Zuniga's restaurant. EAA hangar Calendar 8 and parking lot is on the left. Monterey Bay Chapter Officers Prop Wash By Alice Talnack Chair: Alice Talnack It’s showtime! That is, “Watsonville Fly-In & Airshow 2011” showtime. Vice-Chair: Donna Crane-Bailey Secretary: Mona Kendrick This month’s MB99s meeting will be held at 6:00 p.m. instead of our regu- Treasurer: Sarah Chauvet lar 7:00 p.m. time. That gives us time to enjoy our traditional potluck din- Past Chair: Michaele Serasio Logbook Editor: Dena Taylor ner before we roll up our sleeves and get to work on what we need to do Phone: 831-462-5548 for our airshow responsibility of Pilot Registration. -

Felix A. Soto Taro, Ph.D., PMP Aspiring NASA Astronaut Candidate

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20120006541 2019-08-30T19:56:01+00:00Z NASA Astronaut Selection and Training Overview by Felix A. Soto Taro, Ph.D., PMP Aspiring NASA Astronaut Candidate March 2012 Agenda • Definition • Categories • Overview of Astronaut Selection Process - Qualifications - Interviews - Training - Steps • Astronauts Hobbies • Recommendations • Some Useful Websites Definition of Astronaut • The term "astronaut" derives from the Greek words meaning "space sailor," and refers to all who have been launched as crew members aboard NASA spacecraft bound for orbit and beyond. • Since the inception of NASA's human space flight program, we have also maintained the term "astronaut" as the title for those selected to join the NASA corps of astronauts who make "space sailing" their career profession. • The term "cosmonaut" refers to those space sailors who are members of the Russian space program. Definition of Astronaut (continued) • The crew of each launched spacecraft is made up of astronauts and/or cosmonauts. • The crew assignments and duties of commander, pilot, Space Shuttle mission specialist, or International Space Station flight engineer are drawn from the NASA professional career astronauts. •A special category of astronauts typically titled "payload specialist" refers to individuals selected and trained by commercial or research organizations for flights of a specific payload on a space flight mission. At the present time, these payload specialists may be cosmonauts or astronauts designated by the international partners, individuals selected by the research community, or a company or consortia flying a commercial payload aboard the spacecraft. Space Flyers Categories • Active astronauts are U.S. astronauts who are currently eligible for flight assignment, including those who are assigned to crews. -

Arlington Springs Man” Resource Summary: Students Begin by Reading the Article and Marking the Text

“Arlington Springs Man” Resource Summary: Students begin by reading the article and marking the text. Students then watch the video segment and engage in a class discussion and personal reflection. Next students use information from the article and video to create a “One-Pager” as a summative representation of their learning. Subject Areas: Geoscience Processes, Fossils, Relative and Absolute Dating Grade Level Range: 7th-8th Grade Standards: MS- Construct an explanation based on evidence for how geoscience processes ESS2-2. have changed Earth's surface at varying time and spatial scales. MS- Analyze and interpret data on the distribution of fossils and rocks, continental ESS2-3 shapes, and seafloor structures to provide evidence of the past plate motions. Resource Provided By: Kalley Ridgway, 7th Grade Science, La Colina Junior High, Santa Barbara Unified School District Resource Details: *Lesson designed to follow a learning segment on fossils and relative/absolute dating. Plan is divided into a 3-day learning segment (150 minutes total). Day 1: Students start by watching the 9 min. video segment: Arlington Springs Man (https://channelislands.squarespace.com/tales/arlington-springs-man). Students are provided with questions to answer while watching the video. Question ideas: • Why is it helpful to paleontologists that the Channel Islands have no burrowing animals? • Where did pygmy mammoths come from? How did they get on the islands? • When do they believe pygmy mammoths disappeared? • Who was given the nickname “The Last of the Bone -

Printable Press Release

Press Release Patterson helps prepare astronauts for future visit to asteroid (October 13, 2011) Professor Mark Patterson of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, an aquanaut with several previous trips to “inner space” aboard the Aquarius underwater habitat, will assist a team of NASA astro- nauts as they visit the habitat from October 17-29 to develop techniques for a planned future trip to an asteroid. Patterson is part of the science support team for NEEMO 15—the latest mission of the NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations project. NEEMO sends groups of NASA astronauts and engineers to live in the Aquarius undersea research station as training for work in the weightlessness of outer space. Patterson, Director of the Autonomous Systems Laboratory at VIMS, is a pioneer in the development and use of underwa- ter robots for marine research. His role during the upcoming 13-day NEEMO mission will be to assist the aquanauts as they deploy and operate an oceanographic sensor that will be Aquanauts: Professor Mark Patterson (2nd from mounted atop a one-person DeepWorker submarine. Patterson R) with a group of fellow aquanauts during a will assist on the first five days of the mission. 2004 dive from the Aquarius underwater habitat. “For the NEEMO 15 mission—the first in what will be many dress rehearsals for going to an asteroid—I’ll be flying an ocean profiler on DeepWorker,” says Patterson. The instrument—which Patterson has previously deployed on his autonomous underwater vehicle Fetch—measures ocean acidity, levels of dissolved oxygen and carbon dioxide, and water temperature. -

Fire History on the California Channel Islands Spanning Human Arrival in the Americas

Page 1 of 27 For the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 1 2 3 4 Fire history on the California Channel Islands 5 6 spanning human arrival in the Americas 7 8 Mark Hardiman[1], Andrew C. Scott[2], Nicholas Pinter[3], 9 10 R. Scott Anderson[4], Ana Ejarque[5,6], Alice Carter-Champion[7], 11 Richard Staff[8] 12 1 Department of Geography, University of Portsmouth, U.K. 13 2 Department of Earth Sciences, Royal Holloway, University of London, U.K. 14 3 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California Davis, U.S.A 15 4 School of Earth Sciences and Environmental Sustainability, Northern Arizona University, U.S.A. 16 5 CNRS, UMR 6042, GEOLAB, 4 rue Ledru, F-63057 Clermont-Ferrand cedex 1, France. 17 6 Université Clermont Auvergne, Université Blaise Pascal, GEOLAB, BP 10448, F-63000 Clermont- 18 Ferrand, France. 7 Department of Geography, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, Surrey, UK. 19 8 Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU), Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art 20 (RLAHA), University of Oxford, Dyson Perrins Building, South Parks Road, Oxford, UK. 21 22 Keywords: Fire, Charcoal, Radiocarbon dating, Arlington Springs Man, Clovis Culture, Landscape history, 23 Islands 24 25 Summary 26 27 28 Recent studies have suggested that the first arrival of humans in the Americas during the end of the 29 last Ice Age is associated with marked anthropogenic influences on landscape, in particular with the 30 31 use of fire which would have given even small populations the ability to have broad impacts on the 32 landscape. -

Women in STEM: Hidden Figures, Modern Figures

Science Briefing February 2, 2017 Kimberly Arcand (Chandra/SAO) Dr. Jedidah C. Isler (Vanderbilt University) Women in STEM: Dr. Cady Coleman (Retired USAF, Former Astronaut) Hidden Figures, Modern Figures Dr. Julie McEnery (NASA GSFC) Facilitator: Jessica Kenney (STScI) 1 Additional Resources http://nasawavelength.org/list/1642 Video: VanguardSTEM: Conversation with Margot Lee Shetterly Webinar: STAR_Net – Wed. Feb. 15 – Girls STEAM Ahead with NASA Activities: Coloring the Universe (with Pencil Code) Observing with NASA Websites: Women in Science VanguardSTEM Women@NASA Women in the High Energy Universe Women’s History Month 2016 Exhibits: Here, There, and Everywhere AstrOlympics Light: Beyond the Bulb From Earth to the Universe Visions of the Universe 2 Kim Arcand Visualization Lead [email protected] @kimberlykowal (Twitter, IG) 3 4 As of 2011, women made up only about 26% of U.S. STEM workers 5 Computer science is the only field in science, engineering and mathematics in which the number of women receiving bachelors degrees has decreased since 2002—even after it showed a modest increase in recent years. (Larson, 2014) 6 According to studies, contributing factors include: • a culture that encourages young women to play with dolls rather than robots and pursue traditionally female careers • a self-perpetuating stereotype that a programmer is a white male. (Larson, 2014) 7 Why should we care? By 2020, it is estimated that there will be 1.4 million computer-science related jobs available, in the U.S. but: Only 400,000 CS graduates to fill them. 8 Medication Why Women can experience more and varied side effects from many medications than men do because should such medicines can be biased towards male subjects we care? (Beerya & Zucker) Engineering Better job security and Automobile air bags have been pay but also, more and more dangerous for women of varied viewpoints.