Thermal Dependence of Water and Electrolyte Excretion in Two Species of Lizards*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crocodile Geckos Or Other Pets, Visit ©2013 Petsmart Store Support Group, Inc

SHOPPING LIST CROCODILE Step 1: Terrarium The standard for pet care 20-gallon (20-24" tall) or larger terrarium GECKO The Vet Assured Program includes: Screen lid, if not included with habitat Tarentola mauritanica • Specific standards our vendors agree to meet in caring for and observing pets for Step 2: Decor EXPERIENCE LEVEL: INTERMediate common illnesses. Reptile bark or calcium sand substrate • Specific standards for in-store pet care. Artificial/natural rock or wood hiding spot • The PetSmart Promise: If your pet becomes ill and basking site during the initial 14-day period, or if you’re not satisfied for any reason, PetSmart will gladly Branches for climbing and hiding replace the pet or refund the purchase price. Water dishes HEALTH Step 3: Care New surroundings and environments can be Heating and Lighting stressful for pets. Prior to handling your pet, give Reptile habitat thermometers (2) them 3-4 days to adjust to their new surroundings Ceramic heat emitter and fixture or nighttime while monitoring their behavior for any signs of bulb, if necessary stress or illness. Shortly after purchase, have a Lifespan: Approximately 8 years veterinarian familiar with reptiles examine your pet. Reptile habitat hygrometer (humidity gauge) PetSmart recommends that all pets visit a qualified Basking spot bulb and fixture Size: Up to 6” (15 cm) long veterinarian annually for a health exam. Lamp stand for UV and basking bulbs, Habitat: Temperate/Arboreal Environment if desired THINGS TO WATCH FOR Timer for light and heat bulbs, if desired • -

Cretaceous Fossil Gecko Hand Reveals a Strikingly Modern Scansorial Morphology: Qualitative and Biometric Analysis of an Amber-Preserved Lizard Hand

Cretaceous Research 84 (2018) 120e133 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Cretaceous Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/CretRes Cretaceous fossil gecko hand reveals a strikingly modern scansorial morphology: Qualitative and biometric analysis of an amber-preserved lizard hand * Gabriela Fontanarrosa a, Juan D. Daza b, Virginia Abdala a, c, a Instituto de Biodiversidad Neotropical, CONICET, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales e Instituto Miguel Lillo, Universidad Nacional de Tucuman, Argentina b Department of Biological Sciences, Sam Houston State University, 1900 Avenue I, Lee Drain Building Suite 300, Huntsville, TX 77341, USA c Catedra de Biología General, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Tucuman, Argentina article info abstract Article history: Gekkota (geckos and pygopodids) is a clade thought to have originated in the Early Cretaceous and that Received 16 May 2017 today exhibits one of the most remarkable scansorial capabilities among lizards. Little information is Received in revised form available regarding the origin of scansoriality, which subsequently became widespread and diverse in 15 September 2017 terms of ecomorphology in this clade. An undescribed amber fossil (MCZ Re190835) from mid- Accepted in revised form 2 November 2017 Cretaceous outcrops of the north of Myanmar dated at 99 Ma, previously assigned to stem Gekkota, Available online 14 November 2017 preserves carpal, metacarpal and phalangeal bones, as well as supplementary climbing structures, such as adhesive pads and paraphalangeal elements. This fossil documents the presence of highly specialized Keywords: Squamata paleobiology adaptive structures. Here, we analyze in detail the manus of the putative stem Gekkota. We use Paraphalanges morphological comparisons in the context of extant squamates, to produce a detailed descriptive analysis Hand evolution and a linear discriminant analysis (LDA) based on 32 skeletal variables of the manus. -

House Gecko Hemidactylus Frenatus

House Gecko Hemidactylus frenatus LIFE SPAN: 5-10 years AVERAGE SIZE: 3-5 inches CAGE TEMPS: Day Temps – 75-90 0 F HUMIDITY: 60-75% Night Temps – 65-75oF If temp falls below 65° at night, may need supplemental infrared or ceramic heat. WILD HISTORY: Common house geckos are originally from Southeast Asia, but have established non-native colonies in other parts of the world including Australia, the U.S., Central & South America, Africa and Asia. These colonies were most likely established by geckos who hitched rides on ships and cargo into new worlds. Interestingly, the presence or call of a house gecko can be seen as the harbinger of either good or bad luck – depending upon what part of the world the gecko is in. PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTCS: House geckos generally have a yellow-tan or whitish body with brown spots or blotches. The skin on the upper surface of the body has a granular look and feel. The skin on the underbelly is smooth. These geckos have the famous sticky feet that allow them to walk up and down glass without effort. The pads of their feet are actually made up of thousands of tiny, microscopic hairs. House geckos have extremely delicate skin. For this reason, along with the fact that they are easily stressed, they should not be regularly handled. NORMAL BEHAVIOR & INTERACTION: Nocturnal (most active at night). House geckos are very fast- moving, agile lizards. Handling is not recommended. House geckos will drop their tails (lose them) when trying to escape a predator, because of stress, or from constriction from un-shed skin. -

Mitochondrial Introgression Via Ancient Hybridization, and Systematics of the Australian Endemic Pygopodid Gecko Genus Delma Q ⇑ Ian G

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 94 (2016) 577–590 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Mitochondrial introgression via ancient hybridization, and systematics of the Australian endemic pygopodid gecko genus Delma q ⇑ Ian G. Brennan , Aaron M. Bauer, Todd R. Jackman Department of Biology, Villanova University, 800 Lancaster Avenue, Villanova, PA 19085, USA article info abstract Article history: Of the more than 1500 species of geckos found across six continents, few remain as unfamiliar as the Received 11 May 2015 pygopodids – Family Pygopodidae (Gray, 1845). These gekkotans are limited to Australia (44 species) Revised 21 September 2015 and New Guinea (2 species), but have diverged extensively into the most ecologically diverse limbless Accepted 6 October 2015 radiation save Serpentes. Current phylogenetic understanding of the family has relied almost exclusively Available online 23 October 2015 on two works, which have produced and synthesized an immense amount of morphological, geograph- ical, and molecular data. However, current interspecific relationships within the largest genus Delma Gray Keywords: 1831 are based chiefly upon data from two mitochondrial loci (16s, ND2). Here, we reevaluate the inter- Mitochondrial capture specific relationships within the genus Delma using two mitochondrial and four nuclear loci (RAG1, Introgression Biogeography MXRA5, MOS, DYNLL1), and identify points of strong conflict between nuclear and mitochondrial geno- Pygopodidae mic data. We address mito-nuclear discordance, and remedy this conflict by recognizing several points of Gekkota mitochondrial introgression as the result of ancient hybridization events. Owing to the legacy value and intraspecific informativeness, we suggest the continued use of ND2 as a phylogenetic marker. -

The First Confirmed Records of the Mediterranean House Geckos, Hemidactylus Turcicus (Squamata: Gekkonidae) in Bosnia and Herzegovina

BIHAREAN BIOLOGIST 14 (2): 120-121 ©Biharean Biologist, Oradea, Romania, 2020 Article No.: e202301 http://biozoojournals.ro/bihbiol/index.html The first confirmed records of the Mediterranean house geckos, Hemidactylus turcicus (Squamata: Gekkonidae) in Bosnia and Herzegovina Goran ŠUKALO1,*, Dejan DMITROVIĆ1, Sonja NIKOLIĆ2, Ivana MATOVIĆ1, Rastko AJTIĆ3 and Ljiljana TOMOVIĆ2 1. University of Banja Luka, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Mladena Stojanovića 2, 78000 Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. 2. University of Belgrade, Faculty of Biology, Institute of Zoology. Studentski trg 16, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia. 3. Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia, 91 Dr Ivana Ribara Street, 11070 Belgrade, Serbia. * Corresponding author, G. Šukalo, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 16. February 2020 / Accepted: 14. June 2020 / Available online: 20. June 2020 / Printed: December 2020 Abstract. Here we provide the first confirmed records of Hemidactylus turcicus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although this species was for a long time considered common in Bosnia and Herzegovina and it is included in the species list of the country, clear evaluation of the available scientific literature revealed the species presence in the country was never provided. Therefore, the aim of the note is the confirmation of H. turcicus presence in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Key words: historical records, range extension, Adriatic coast, Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Mediterranean house gecko, Hemidactylus turcicus (Lin- available relevant literature records and the authors’ field- naeus, 1758), is an autochthonous and widely distributed work. representative of the Mediterranean fauna of southern Eu- On July 21, 2017, in the area of the city of Neum (Federa- rope, western Asia and northern Africa; also, it was intro- tion of Bosnia and Herzegovina: 42.932N, 17.593E, 16 m a.s.l, duced into North and Central America, and in numerous Fig. -

La Brea and Beyond: the Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas

La Brea and Beyond: The Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas Edited by John M. Harris Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Science Series 42 September 15, 2015 Cover Illustration: Pit 91 in 1915 An asphaltic bone mass in Pit 91 was discovered and exposed by the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science and Art in the summer of 1915. The Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History resumed excavation at this site in 1969. Retrieval of the “microfossils” from the asphaltic matrix has yielded a wealth of insect, mollusk, and plant remains, more than doubling the number of species recovered by earlier excavations. Today, the current excavation site is 900 square feet in extent, yielding fossils that range in age from about 15,000 to about 42,000 radiocarbon years. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Archives, RLB 347. LA BREA AND BEYOND: THE PALEONTOLOGY OF ASPHALT-PRESERVED BIOTAS Edited By John M. Harris NO. 42 SCIENCE SERIES NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Luis M. Chiappe, Vice President for Research and Collections John M. Harris, Committee Chairman Joel W. Martin Gregory Pauly Christine Thacker Xiaoming Wang K. Victoria Brown, Managing Editor Go Online to www.nhm.org/scholarlypublications for open access to volumes of Science Series and Contributions in Science. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Los Angeles, California 90007 ISSN 1-891276-27-1 Published on September 15, 2015 Printed at Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas PREFACE Rancho La Brea was a Mexican land grant Basin during the Late Pleistocene—sagebrush located to the west of El Pueblo de Nuestra scrub dotted with groves of oak and juniper with Sen˜ora la Reina de los A´ ngeles del Rı´ode riparian woodland along the major stream courses Porciu´ncula, now better known as downtown and with chaparral vegetation on the surrounding Los Angeles. -

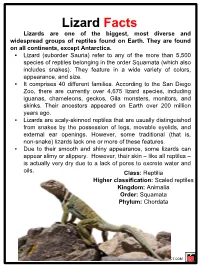

Lizard Facts Lizards Are One of the Biggest, Most Diverse and Widespread Groups of Reptiles Found on Earth

Lizard Facts Lizards are one of the biggest, most diverse and widespread groups of reptiles found on Earth. They are found on all continents, except Antarctica. ▪ Lizard (suborder Sauria) refer to any of the more than 5,500 species of reptiles belonging in the order Squamata (which also includes snakes). They feature in a wide variety of colors, appearance, and size. ▪ It comprises 40 different families. According to the San Diego Zoo, there are currently over 4,675 lizard species, including iguanas, chameleons, geckos, Gila monsters, monitors, and skinks. Their ancestors appeared on Earth over 200 million years ago. ▪ Lizards are scaly-skinned reptiles that are usually distinguished from snakes by the possession of legs, movable eyelids, and external ear openings. However, some traditional (that is, non-snake) lizards lack one or more of these features. ▪ Due to their smooth and shiny appearance, some lizards can appear slimy or slippery. However, their skin – like all reptiles – is actually very dry due to a lack of pores to excrete water and oils. Class: Reptilia Higher classification: Scaled reptiles Kingdom: Animalia Order: Squamata Phylum: Chordata KIDSKONNECT.COM Lizard Facts MOBILITY All lizards are capable of swimming, and a few are quite comfortable in aquatic environments. Many are also good climbers and fast sprinters. Some can even run on two legs, such as the Collared Lizard and the Spiny-Tailed Iguana. LIZARDS AND HUMANS Most lizard species are harmless to humans. Only the very largest lizard species pose any threat of death. The chief impact of lizards on humans is positive, as they are the main predators of pest species. -

Description of a New Flat Gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae: Afroedura) from Mount Gorongosa, Mozambique

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320043814 Description of a new flat gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae: Afroedura) from Mount Gorongosa, Mozambique Article in Zootaxa · September 2017 DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4324.1.8 CITATIONS READS 2 531 8 authors, including: William R Branch Jennifer Anna Guyton Nelson Mandela University Princeton University 250 PUBLICATIONS 4,231 CITATIONS 7 PUBLICATIONS 164 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Andreas Schmitz Michael Barej Natural History Museum of Geneva Museum für Naturkunde - Leibniz Institute for Research on Evolution and Biodiver… 151 PUBLICATIONS 2,701 CITATIONS 38 PUBLICATIONS 274 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Monitoring and Managing Biodiversity Loss in South-East Africa's Montane Ecosystems View project Ad hoc herpetofauna observations View project All content following this page was uploaded by Jennifer Anna Guyton on 27 September 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Zootaxa 4324 (1): 142–160 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2017 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4324.1.8 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:B4FF9A5F-94A7-4E75-9EC8-B3C382A9128C Description of a new flat gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae: Afroedura) from Mount Gorongosa, Mozambique WILLIAM R. BRANCH1,2,13, JENNIFER A. GUYTON3, ANDREAS SCHMITZ4, MICHAEL F. BAREJ5, PIOTR NASKRECKI6,7, HARITH FAROOQ8,9,10,11, LUKE VERBURGT12 & MARK-OLIVER RÖDEL5 1Port Elizabeth Museum, P.O. Box 13147, Humewood 6013, South Africa 2Research Associate, Department of Zoology, Nelson Mandela University, P.O. -

Growth Rates of the Mediterranean Gecko, Hemidactylus Turcicus, in Southwestern Louisiana

Western North American Naturalist Volume 74 Number 1 Article 6 5-23-2014 Growth rates of the Mediterranean gecko, Hemidactylus turcicus, in southwestern Louisiana Mark A. Paulissen Northeastern State University, Tahlequah, OK, [email protected] Harry A. Meyer McNeese State University, Lake Charles, LA, [email protected] Tabatha S. Hibbs Connors State College, Warner, OK, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Part of the Anatomy Commons, Botany Commons, Physiology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Paulissen, Mark A.; Meyer, Harry A.; and Hibbs, Tabatha S. (2014) "Growth rates of the Mediterranean gecko, Hemidactylus turcicus, in southwestern Louisiana," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 74 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol74/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 74(1), © 2014, pp. 71–78 GROWTH RATES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN GECKO, HEMIDACTYLUS TURCICUS, IN SOUTHWESTERN LOUISIANA Mark A. Paulissen1, Harry A. Meyer2, and Tabatha S. Hibbs3 ABSTRACT.—We captured and marked Mediterranean geckos, Hemidactylus turcicus, occupying a one-story building in southwestern Louisiana in 1999–2000 and 2002–2005 and calculated 2 estimates of growth rate: length growth rate (difference in snout–vent length [SVL] between captures divided by time between captures) and mass growth rate (dif- ference in gecko mass between captures divided by time between captures). -

GECKOS Introduction Geckos Are the Most Primitive Group of Lizards

GECKOS Introduction Geckos are the most primitive group of lizards. There are more than 750 species, and they are second only to the skinks in numbers and distribution. Because they are such a large group, there are exceptions to many familiar gecko characteristics. Most geckos have a spectacle similar to that seen in snakes, but some types have true eyelids. Most geckos are cryptically colored and nocturnal, but a few are brilliantly colored and active by day. These diurnal forms have round pupils, while most geckos have vertical pupils. One of the most well known of gecko characteristics is the widened clinging toe pads, enabling the animals to crawl up vertical surfaces and even across ceilings. Again, there are some gecko forms lacking these pads and most of these are terrestrial. They come from tropical and subtropical climates around the world, as well as deserts. Some live only in close association with man. The only factor limiting their distribution is their inability to survive prolonged freezing temperatures. There are 5 native U.S. species and, at last count, 5 introduced species that have taken up residence in the United States. Geckos are among the most vocal lizards. “Gecko” itself is an approximation of the raucous cry of the Asian tokay gecko. One caution to the first time gecko-culturist, gecko tails break off. Please be very careful when moving your animal. Even though the tails may eventually regrow, they usually are not as nicely formed as original. Captivity Requirements Because of their wide distribution and physical diversity one must consider the individual type of gecko when setting up suitable house and meeting water, dietary, and breeding requirements. -

Characterization of Five Complete Cyrtodactylus Mitogenome Structures Reveals Low Structural Diversity and Conservation of Repeated Sequences in the Lineage

Characterization of five complete Cyrtodactylus mitogenome structures reveals low structural diversity and conservation of repeated sequences in the lineage Prapatsorn Areesirisuk1,2,3, Narongrit Muangmai3,4, Kirati Kunya5, Worapong Singchat1,3, Siwapech Sillapaprayoon1,3, Sorravis Lapbenjakul1,3, Watcharaporn Thapana1,3,6, Attachai Kantachumpoo1,3,6, Sudarath Baicharoen7, Budsaba Rerkamnuaychoke2, Surin Peyachoknagul1,8, Kyudong Han9 and Kornsorn Srikulnath1,3,6,10 1 Laboratory of Animal Cytogenetics and Comparative Genomics (ACCG), Department of Genetics, Faculty of Science, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand 2 Human Genetic Laboratory, Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand 3 Animal Breeding and Genetics Consortium of Kasetsart University (ABG-KU), Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand 4 Department of Fishery Biology, Faculty of Fisheries, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand 5 Nakhon Ratchasima Zoo, Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand 6 Center for Advanced Studies in Tropical Natural Resources, National Research University-Kasetsart University (CASTNAR, NRU-KU, Thailand), Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand 7 Bureau of Conservation and Research, Zoological Park Organization under the Royal Patronage of His Majesty the King, Bangkok, Thailand 8 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand 9 Department of Nanobiomedical Science & BK21 PLUS NBM Global Research Center for Regenerative Medicine, Dankook University, Cheonan, Republic of Korea 10 Center of Excellence on Agricultural Biotechnology: (AG-BIO/PERDO-CHE), Bangkok, Thailand ABSTRACT Submitted 30 July 2018 Accepted 15 November 2018 Mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) of five Cyrtodactylus were determined. Their Published 13 December 2018 compositions and structures were similar to most of the available gecko lizard Corresponding author mitogenomes as 13 protein-coding, two rRNA and 22 tRNA genes. -

Molecular Evidence for Gondwanan Origins of Multiple Lineages Within A

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2009) 36, 2044–2055 ORIGINAL Molecular evidence for Gondwanan ARTICLE origins of multiple lineages within a diverse Australasian gecko radiation Paul M. Oliver1,2* and Kate L. Sanders1 1Centre for Evolutionary Biology and ABSTRACT Biodiversity, University of Adelaide and Aim Gondwanan lineages are a prominent component of the Australian 2Terrestrial Vertebrates, South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA, terrestrial biota. However, most squamate (lizard and snake) lineages in Australia Australia appear to be derived from relatively recent dispersal from Asia (< 30 Ma) and in situ diversification, subsequent to the isolation of Australia from other Gondwanan landmasses. We test the hypothesis that the Australian radiation of diplodactyloid geckos (families Carphodactylidae, Diplodactylidae and Pygopodidae), in contrast to other endemic squamate groups, has a Gondwanan origin and comprises multiple lineages that originated before the separation of Australia from Antarctica. Location Australasia. Methods Bayesian (beast) and penalized likelihood rate smoothing (PLRS) (r8s) molecular dating methods and two long nuclear DNA sequences (RAG-1 and c-mos) were used to estimate a timeframe for divergence events among 18 genera and 30 species of Australian diplodactyloids. Results At least five lineages of Australian diplodactyloid geckos are estimated to have originated > 34 Ma (pre-Oligocene) and basal splits among the Australian diplodactyloids occurred c. 70 Ma. However, most extant generic and intergeneric diversity within diplodactyloid lineages appears to post-date the late Oligocene (< 30 Ma). Main conclusions Basal divergences within the diplodactyloids significantly pre-date the final break-up of East Gondwana, indicating that the group is one of the most ancient extant endemic vertebrate radiations east of Wallace’s Line.