Knitting Skills2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

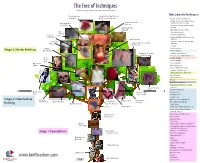

Tree of Techniques

The Tree of Techniques Click any image or technique for more information Skills Learned As You Progress Tiny Complicated “What Will I Do With This Yarn” Seamed Toy Made-Up Custom Pattern Writing Up Your Own Patterns Making Up Your Own Patterns Based Complex Custom-Fit Easy Teddy Bear On the Yarn That You Have Garments or Plush Toy Custom-t Garments with Machine Knitting with Wire Sewing and Beads Tiny Knitted Objects or Toys Tiny Customized Projects Seamed Freeform Embellishing Freeform Toy Embellishing Knitting with Wire, Beads, and Other Custom Sweater Materials Customized Complex Charted Lace Project with Mittens Complex Charted Lace Shawl Fine Yarn with Fine Yarn Steeking Complex Custom Sweaters Stage 3: Master Knitting Fair-Isle Hat Brioche Knitting Knitted or Crocheted Complex Fair-Isle Projects Embellishments Knitted/crocheted Embellishments 2-Color Double-Knitting Brioche Entrelac Knitting Cowl Easy Fair-Isle Easy Teddy Bear Mittens Moebius Knitting Advanced Pattern-Reading Complex Fair-Isle Charts Cabling Without a Cable Needle Basic Sweaters Intermediate Lace Mittens Basic Fair-Isle Knitting Cabling from Patterns and Charts Moebius Scarf or Easy Lace Bowl Continental Knitting Double-Knit Entrelac Scarf, Two-at-a-time Scarf Purse, or Pillow Top-Down Sock Toe-Up Socks Better Cast-Ons and Bind-Os Stage 2: Intermediate Complex Intermediate Easy Mittens Easy Lace Scarf Fair-Isle Pillow Easy Felted Bag Lace Hat Wrap & Turn (Short Rows) Knitting Easy Fair-Isle Bag Basic Toe-Up Socks Tiny Projects Basic Hat Basic Pullover Knitting In -

Woolstock Yarn Shop

4876 Butler Rd Glyndon, MD 21071 410-517-1020 Woolstock Yarn Shop www.woolstock.com Upcoming Classes & Events September-October 2013 What’s Happening at Woolstock “..the number one reason We’re so excited about the fall...new yarns, patterns, new adventures. We’re starting out with some new classes and some old favorites we know are always requested. knitters knit is because they are so smart that they need Don’t know how to knit (or crochet)? Let us show you. knitting to make boring things Learn or Switch … to Continental Knitting interesting. Knitters are so compellingly clever that they Experienced knitters, as well as people who have never held a knit- ting needle before, can benefit from learning this easy method of simply can't tolerate bore- Continental knitting using the exclusive techniques shown in Leslye’s DVD, The Absolute Best Way to Learn How to Knit (shown at left). dom. It takes more to engage Leslye Solomon has been teaching these techniques for many years and entertain this kind of to sold-out classes at major knitting seminars throughout the country. We offer her class by appointment, so you can easily fit the class into human, and they need an your schedule. We can also accommodate small group classes. This easy, ergonomic method of knitting helps to limit motion, thereby outlet or they get into reducing stress on hands, wrists, and necks. Using this method, seed stitch and rib- trouble.”- bing can be knitted with a fluid, easy motion, making your projects faster and more enjoyable. Continental knitting also adds the extra benefit of a more evenly-knitted fabric. -

M Etamorphosis H At

etamorphosis at M H This Tunisian Crochet design takes full advantage of the slow & beautiful color changes of this Chunky Mochi yarn! The Metamorphosis Hat is a “try it, you’ll like it” project. Even if you don’t crochet and don’t even think you want to learn to crochet, you’ll like this cross between the two. What’s inside ... More online ... Tunisian Intro Tunisian Hat Tunisian Project & Tutorial Photo Tutorial Photos Complete Bonus Scarf Hat Pattern & Blanket Facebook Twitter Pinterest Wordpress Laura Cunitz for KnittingNuances.com Copyright 2013 etamorphosis at nitting uances M H K N From the Designer I don’t crochet, don’t even know how to. So why include this semi- crochet hat on our new knitting web site? Because I‘ve had more people ask me to make them this hat than any other project I’ve knit - ever. To be honest, it’s the long colorway changes that make it so beautiful, not any ingenious designing. It’s gotten to the point where I can finish one in less than two hours. The perfect emergency gift. I had so much fun with them that I made six of them as gifts for my daughter and nieces - each in a different color way.This resulted in at least six more since everyone that sees one has to have one. Pick a brim color that works with multiple Chunky Mochi colors and you can knit several brims from it. You can read more about in on our November 2013 blog post. Keep It Loose You can find more free knitting patterns on our web site including our This is a fast, easy and relaxing project. -

Click Here to See the Yarnover 2020 Brochure

MINNESOTA KNITTERS’ GUILD Presents the 34th Annual Minnesota Knit Together April 24–26, 2020 Crowne Plaza in Plymouth 3131 Campus Drive, Plymouth, Minnesota 55441 Friday April 24 Saturday, April 25 Sunday, April 26 Yarnover Dinner with Keynote Yarnover Classes Monthly Minnesota Speaker: Franklin Habit and Vendor Market Knitters’ Guild meeting Join us at the Crowne Plaza, for a 8:00AM Registration opens “The time is Now!” delicious buffet dinner. Then stay with Susanna Hansson 8:00 AM–5:30 PM Marketplace, free for “Impractical Magic: Oddities 10:00 AM–12:00 PM and Curiosities from Weldon’s 9:00AM–12:00 PM Morning Classes Practical Needlework” with Franklin What does knitting mean to us? Habit. Beginning in the 1880s, and 12:00–2:00 PM Lunch Is it a passion, a purpose, or is it for decades thereafter, the editors included with 3 hour or "just" a way to pass time? of Weldon’s Practical Needlework all day classes Process or product knitting — provided an enormous audience of 2:00 PM–5:00 PM Afternoon Classes; does it matter? Do we value amateur craftswomen with patterns Continuation of All Day Classes. our knitting time? How is that for garments designed to be warm, reflected in what we do? strong, long-lived and, well, practical. 7:30 PM–9:30 PM Yarn Bingo. But Weldon’s had another side, too. Free to attend, cash bar available. There are no right or wrong A side that proposed the knitting of Cost: $180 for full day or $90 for answers but I hope all of you will covers for tennis balls, of knitting half day classes for members. -

A Thematic Analysis of the Material Culture of Artwork Using Knit As an Artistic Medium Rebecca Elaine Schuiling

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations Graduate Capstone Projects 12-12-2013 A thematic analysis of the material culture of artwork using knit as an artistic medium Rebecca Elaine Schuiling Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/theses Part of the Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons Recommended Citation Schuiling, Rebecca Elaine, "A thematic analysis of the material culture of artwork using knit as an artistic medium" (2013). Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations. 564. http://commons.emich.edu/theses/564 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses, and Doctoral Dissertations, and Graduate Capstone Projects at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Thematic Analysis of the Material Culture of Artwork Using Knit as an Artistic Medium by Rebecca E. Schuiling Thesis Submitted to the School of Technology Studies Eastern Michigan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Apparel, Textiles, and Merchandising Thesis Committee: Subhas Ghosh, PhD., Chair Julie Becker, M.S. December 12, 2013 Ypsilanti, Michigan A Thematic Analysis of the Material Culture of Artwork Using Knit as an Artistic Medium ii Dedication To the loving memory, grace and spirit of my beautiful mother, Carol Jean Barnhill, who is always with me in mind, heart, and soul. A Thematic Analysis of the Material Culture of Artwork Using Knit as an Artistic Medium iii Acknowledgements I wish to thank my advisor, Dr. -

Knitting in 21St Century America: the Culture and Ideology of Knitting Groups in Rural Oregon

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-1-2017 Knitting in 21st Century America: The Culture and Ideology of Knitting Groups in Rural Oregon Robin Roemer Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Recommended Citation Roemer, Robin, "Knitting in 21st Century America: The Culture and Ideology of Knitting Groups in Rural Oregon" (2017). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 136. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/136 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Knitting in 21st Century America: The Culture and Ideology of Knitting Groups in Rural Oregon By Robin Roemer An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Isidore Lobnibe, Thesis advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director June 2017 Roemer ii Acknowledgments I wish to thank my advisor Isidore Lobnibe, the Anthropology department, Gavin Keulks and the Honors department, and my mom and dad for their help and support. I also want to thank all of the knitters who were interviewed in this study for sharing their knowledge with me and the knitters of the local group mentioned in this study. I want to thank Awana Black for letting me accompany her to events. Roemer iii Abstract Knitting has existed since the Middle Ages, and continues to thrive well into twenty- first century America. -

Crocheter's Way to Do Continental Knitting So I Am a Crocheter at Heart

Crocheter's way to do Continental Knitting So I am a crocheter at heart and I learned how to knit in English style, but that was time consuming and hard on my wrists that tend to get cists in them. So I tried to learn how to do Continental Knitting. Well, any crocheter will tell you placing the yarn over your top 3 fingers and under your pinky just feels plain wrong. Sure you can do a purl stitch with a flick of a finger but to an avid crocheter it is highly uncomfortable. I know why you put the yarn that way but it makes no sense to my brain and I fumbled around for about 30min and finally I figured out a solution. I am probably by no means the first person to figure this out but eh I needed to do a tutorial. So let's start by how you hold the yarn. If you crochet you hold it your "normal way." For me this is over the pinky under the ring and middle finger and over the index finger of my left hand. Now in the normal continental having the yarn under the middle finger causes all kinds of trouble when you try to do a purl stitch. Fear not! See how I get around the yarn slipping off the index finger when I purl. PART 1: The Purl Stitch You will notice that the yarn is in in my normal crochet position (see above for description). 1. The working yarn must be in front of the needle 2. -

Memory in the Fingers an Exploration of Knitting Through the Lens of Modern Knitters’ Lives by Sinclair Rishel

Memory in the Fingers An exploration of knitting through the lens of modern knitters’ lives By Sinclair Rishel A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford, Mississippi April 2016 Approved by __________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Kathleen Wickham __________________________________ Reader: Ms. Ellen Meacham __________________________________ Reader: Mr. Charlie Mitchell © 2016 Sinclair Rishel ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Acknowledgements I would like to take this opportunity to thank those who have been instrumental in the creation of this thesis. To all of my interviewees, your stories have inspired and excited me. It was my great pleasure to tell each one and I thank you for sharing them with me. I hope I’ve done them justice. To my thesis advisor, Dr. Kathleen Wickham, who has accomplished the marvelous feat of taking a massive and complex project and making it approachable. Thank you for all your help and for being willing to take on an unfamiliar subject and tackle the project in my own language. To my friends and family, who have read, proofread, listened, talked, encouraged, and put up with my lectures and unconventional decorating scheme over the past months. This project could not be what it is without your support and I promise, I will refrain in the future from thumbtacking yarn to the walls. To Knit1 Oxford, who has been a repository of knitting community, information, yarn, and inspiration. Thank you, both for the work you do in bringing great beauty to Oxford and for giving me the opportunity to work and learn in such a wonderful place. -

MEDIEVAL KNITTING in the Middle Ages, a “Hot” New Thread Technology Was Sweeping Europe

MEDIEVAL KNITTING In the Middle Ages, a “hot” new thread technology was sweeping Europe. This new technique made it easier than ever to produce colorful and luxurious textiles. It was eagerly borrowed by Europeans from the Islamic countries around the Mediterranean — along with a lot of other things from the same splendid cultural center, such as alchemy, blackwork embroidery, Greek literature, and the concept of zero. This hot new technology was knitting. It was easy to learn, and fast. Unlike weaving, it didn’t require cumbersome or expensive equipment. With a few pieces of wire and some colored thread, knitting could create anything from elaborate brocade-like designs to nicely fitted stockings to warm woolen caps. History Knitting was once thought to be one of those “timeless arts” that went back forever. But in fact, it seems to have been invented sometime late in the first millennium C.E., perhaps as early as the 8th C. The earliest pieces of surviving knitting — which are all from Islamic countries — are dated by their style of decoration to the 9th, 10th and 11th C. Even these earliest pieces are filled with intricate, multi-colored designs. Most of this material comes from graves and trash heaps in Egypt and other dry places, where textiles are more likely to be preserved. The Islamic connection becomes even stronger when we note that the earliest knitted items in what’s now Western Europe are from Spain, where Islamic influence was strong. These early items include a pair of bishop’s ceremonial gloves (dated around 1245) and two cushion-covers. -

Knitting Style – the Grace of Noble Ladies Or the Speed of Peasant Girls? Anu Pink

64 Best of Studia Vernacula Knitting style – the grace of noble ladies or the speed of peasant girls? Anu Pink Knitting is a textile technique with a global spread, yet the method of holding the yarn and needles differs between geographic areas and cultures. There are three main knitting styles: holding the yarn in the right hand or throw- ing, holding the yarn in the left hand or picking and knitting with the yarn in front of the work and manipulating it with the thumb. Knitting methods have been subject to change over time. People have tried to make the move- ments either faster or, as is the case with 19th century England, more graceful. Estonian knitters stayed true to throwing for centuries and were not waived by German, Russian or Scandinavian knitters. However, picking has become prevalent within the last century following the Finnish example and published materials. Studying the Estonians’ knitting style and comparing this to neigh- bouring countries provides an insight into the development of and influences on Estonian knitting. Keywords: knitting, knitting history, knitting styles, picking, throwing, Continental knitting, English knitting, Portuguese knitting, Estonian knitting Introduction The product of any working task is often considered the most valuable part, and not much value is attributed to the techniques used in production. For the worker, of course, working methods matter, especially while still learning or when trying to increase productivity. There has been very little research on the knitting styles used in Estonia one hundred years ago and how different knitting styles may have gained a foothold. -

The Knitting Reference Library Words by Linda Newington

Inspiring the Generations: The Knitting Reference Library Words by Linda Newington. The Knitting Reference Library (KRL) is part of the University of Southampton Library, and is located at Winchester School of Art, a campus of the University. The KRL was launched at the first In the loop conference in 2008 and is founded on the bibliographic collections of Richard Rutt, Montse Stanley and Jane Waller. Each collector possessed a serious passion for knitting, their individual approaches are illustrated through the resources they collected and established as an essential part of their working lives. The library comprises nearly 2000 books, 425 journal and magazine titles, an estimated 12,000 knitting patterns and hundreds of knitting pattern books. It includes many widely known classic books from the Victorian period through the decades of the twentieth century to the present day. Richard Rutt and the history of hand knitting Richard Rutt (1925-2011) once popularly known as the knitting bishop, was a scholar and knitter known for his classic book A history of hand knitting published by Batsford in 1987, it remains a key text on the subject. I first met Richard Rutt at his home in Falmouth to discuss the generous donation of his library. Many return visits were made to discuss knitters and their books whenever I made a trip down to Cornwall. It was always a pleasure to meet with him and his wife Joan and to chat over tea and cake. I also saw many examples of his and Joan’s knitting including hats, gloves, cardigans, jumpers and coats. -

Knitting Retreat

Registration Form Name ____________________ Address___________________ City ______________________ State _____Zip ________ Phone # __________________ Email ____________________ Male Female Please list any food allergies or special needs ____________________ _________________________ Knitting Retreat Room mate/s _______________ September 27-29, 2013 _________________________ _________________________ Complete this portion, detach and mail with a check, made payable to Clara Masessa, for $170 ($180 if you Fellowship are doing the zip line) Fun Send to: Clara Masessa Kraemer Yarns PO Box 72 Nazareth, PA 18064 GPS Coordinates Latitude: (N) 41.23375 Longitude: (W) 75.30745 Cost: $170 (Includes all meals, classes) Things You Need to Know Location: Class offerings Sleeping Arrangements Pocono Plateau Camp (Class size limited to 15 students) Cabins are dormitory-style & Retreat Center Please number in order of pref- Bunk beds (we are using bottom (www.poconoplateau.org) erence for each class period bunks only) PA-191 & Pocono Plateau Rd Saturday Morning What to bring Cresco, PA 18326 Hand Dying Sleeping bag or sheets & blankets Cables Pillow Check-in Learn to Crochet Friday, September 27th Wash cloth & towel Making Felted Balls 6:30 check-in Learn Continental Knitting Soap & shampoo Rain gear Free Time Leave: Flashlight Sunday September 29th 2:00 p.m. Saturday Afternoon Insect repellent Hand Dying Comfortable casual clothes There is time in the schedule for Fair Isle Sturdy shoes (sandals must have back strap) Relaxing A Bunch of