Holmes V Hatch Ltd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovation Ecosystem

Central Alberta Alberta Real Estate Regional Innovation Wood Buffalo Alberta Biodiversity Regional (CATAPULT) Alberta Industrial Foundation Network for Southern Regional Innovation Monitoring Miistakis Institute Municipality of Heartland Association Tri-region (Spruce Alberta Network Canadian Association Canadian Institute Wood Buffalo Edmonton Grove, Stony Plain, Grande Prairie Edmonton Regional of Petroleum Producers Renewable Fuels County of (TEC Edmonton, Startup Innovation Network Resource BC Bioenergy Alberta Land Parkland County) (Spark!) East Central Alberta Grande Prairie Association Wetaskiwin Municipal District Edmonton, NABI, NAIT) East MEGlobal Industries Suppliers Association Land Trust Stewardship Regional Innovation Regional Innovation Petroleum Services Association Alberta Centre Pembina Institute of Greenview Central Central Alberta Alliance Calgary Network Network Petroleum Association of Bioenergy Regional Innovation Concordia Technology Alliance Canadian Lumber St. Paul Town of Sundre University Athabasca NOVA Chemicals Canada BioAlberta Producers Waterton Biosphere Athabasca County Southern Alberta Network Canada Standards Association Alberta Land Medicine Hat University Reserve Association City of Red Deer (TecConnect) Southeast Alberta Transalta Institute (APEX) Canadian (WBRA) City of Edmonton Calgary Regional Regional Innovation MacEwan Enerplus BioTalent University University of Sundre Clean Power Innovation Network University Canada ENVIRONMENTAL Sturgeon County Red Deer County of Alberta Lethbridge Petroleum -

NI 43-101 Preliminary Economic Assessment Report

N.I. 43-101 TECHNICAL REPORT & PRELIMINARY ECONOMIC ASSESSMENT FOR THE TURNAGAIN PROJECT British Columbia, Canada Report date: November 18, 2020 Effective date: October 28, 2020 Prepared for: Suite 203 – 700 West Pender St., Vancouver, BC, V6C 1G8 www.gigametals.com Prepared by: 1066 W. Hastings St., Vancouver, BC, V6E 3X2 Qualified Persons Ian Thompson, P.Eng., Persio Rosario, P.Eng., Evan Jones, P.Eng., Gerald Schwab, P.Eng., & Stefan Hlouschko, P.Eng. – Hatch Ltd. • Garth Kirkham, P.Geo – Kirkham Geosystems • Daniel Friedman, P.Eng. – Knight Piésold • Ron Monk, P.Eng. – Kerr Wood Leidal • Chris Martin, C.Eng. MIMMM – Blue Coast Metallurgy • Andrew Mitchell, PhD, C.Eng – Wood Mackenzie Kirkham Geosystems Ltd. IMPORTANT NOTICE TO READER This report was prepared by the qualified persons (QPs) listed in Table 2.1. Each QP assumes responsibility for those sections or areas of this report that are referenced opposite their name in Table 2.1. None of the QPs, however, accepts any responsibility or liability for the sections or areas of this report that were prepared by other QPs. This report was prepared to allow Giga Metals Corporation (the “Owner”) to reach informed decisions respecting the development of the Turnagain Project. Except for the purposes legislated under provincial securities law, any use of this report by any third party is at that party's sole risk, and none of the contributors shall have any liability to any third party for any such use for any reason whatsoever, including negligence. This report is intended to be read as a whole, and sections should not be read or relied upon out of context. -

Copper Shines Brightly for Mcewen Mining - Enhanced Economics of Los Azules

COPPER SHINES BRIGHTLY FOR MCEWEN MINING - ENHANCED ECONOMICS OF LOS AZULES $2.2 Billion After-Tax NPV@8% and IRR of 20.1% 3.6 Year Payback at $3.00/lb. Copper and 36 Year Mine Life 415 Million lbs. Average Annual Copper Production For The First 10 Years $1.11/lb. Copper Average Cash Production Cost (C1) For First 10 Years TORONTO, Sep 7, 2017 - McEwen Mining Inc. (NYSE: MUX) (TSX: MUX) is pleased to announce the results of a new Preliminary Economic Assessment (PEA) on its 100% owned Los Azules Copper Project. The results of the 2017 PEA demonstrate that Los Azules is a robust, high margin, rapid pay-back, and long-life open pit mine at current copper, gold and silver prices. The 2017 PEA was prepared by Hatch Ltd., a global multidisciplinary management, engineering and development consultancy known for leadership in mining innovation, under the direction of Donald Brown C. P. Eng (Senior Vice President of Projects for McEwen Mining) with contributions from other industry specialists. The reforms introduced by the government of Argentina under the leadership of President Macri to encourage mining investment by eliminating taxes on exported mineral concentrates was a key factor driving the new PEA for Los Azules. “Los Azules is a giant porphyry copper deposit that offers tremendous potential to generate wealth for McEwen Mining shareowners and other stakeholders,” said Rob McEwen, Chairman and Chief Owner. “Our next steps are to advance permitting and prefeasibility/feasibility studies to move Los Azules towards production.” Los Azules is located in the San Juan Province of north-western Argentina. -

Our Members Our Members

SUBSCRIBE TO MAC NEWS Home > Members & Partners > Our Members Our Members Members and associate members of the Mining Association of Canada play a vital role in ensuring the continued strength and sustainability of Canada’s mining industry. Our members account for most of Canada’s production of base and precious metals, uranium, diamonds, metallurgical coal and mined oil sands, and are actively engaged in mineral exploration, mining, smelting, rening and semi-fabrication. Full Members AGNICO EAGLE MINES LIMITED ALEXCO RESOURCE CORP. ARCELORMITTAL MINES CANADA B2GOLD CORP. BAFFINLAND BARRICK BHP CAMECO CORPORATION CANADIAN NATURAL RESOURCES LIMITED COPPER MOUNTAIN MINING CORPORATION DE BEERS CANADA INC. ELDORADO GOLD EQUINOX GOLD CORPORATION EXCELLON RESOURCES INC. FIRST QUANTUM MINERALS LTD. FORT HILLS LIMITED PARTNERSHIP GLENCORE CANADA CORPORATION HD MINING INTERNATIONAL LTD. HECLA QUÉBEC INC. HUDBAY MINERALS INC. IAMGOLD CORPORATION IMPALA CANADA LIMITED IRON ORE COMPANY OF CANADA KINROSS GOLD CORPORATION KIRKLAND LAKE GOLD LUNDIN FOUNDATION LUNDIN MINING CORPORATION MCEWEN MINING NEW GOLD INC. NEWMONT NEXGEN ENERGY LTD. NORONT RESOURCES LTD. NORZINC LTD. (FORMERLY CANADIAN ZINC CORPORATION) NYRSTAR CANADA (HOLDINGS) LTD. PAN AMERICAN SILVER CORP. RIO TINTO CANADA RIVERSDALE RESOURCES LIMITED ROYAL CANADIAN MINT SHERRITT INTERNATIONAL STAR DIAMOND CORPORATION SUNCOR ENERGY INC. SYNCRUDE CANADA LTD. TECK RESOURCES LIMITED TREVALI VALE WESTERN COPPER AND GOLD YAMANA GOLD INC. Associates AUSENCO LIMITED AVALON ADVANCED MATERIALS INC. BARR ENGINEERING AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE CANADA LTD. BBA INC. BENNETT JONES LLP BGC ENGINEERING INC. BUREAU VERITAS LABORATORIES CANADA NORTH ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES LTD. CEMENTATION CANADA INC. CEMI - CENTRE FOR EXCELLENCE IN MINING INNOVATION CHAMBER OF MARINE COMMERCE CHARLES TENNANT & COMPANY (CANADA) LTD. -

Changing Times — the Challenges and Risks of Managing Aging Infrastructure Under a New Financial Reality

United States Society on Dams Changing Times — The Challenges and Risks of Managing Aging Infrastructure Under a New Financial Reality 33rd Annual USSD Conference Phoenix, Arizona, February 11-15, 2013 CONTENTS Plenary Session USACE Experience in Performing Constructability Reviews ...............1 David Paul, Mike Zoccola and Vanessa Bateman, Corps of Engineers; and Dan Hertel, Engineering Solutions, LLC Levees Levee Evaluation with Ground-Penetrating Radar ....................3 Hussein Khalefa Chlaib, Haydar Al-Shukri, Hanan Mahdi, M. Mert Su, Aycan Catakli and Najah Abd, University of Arkansas at Little Rock How Enhanced and Economically Viable Engineering Analysis Can Help Levee Owners Evaluate Their Inventory in Response to FEMA’s Proposed Approach for Non-Accredited Levees ..................................5 Todd Mitchell, Paul Grosskruger and Cornelia Dean, Fugro Constultants, Inc.; and Bob Woldringh, Furgro Engineers, BV Use of Fragility Curves in Assigning Levee Remediation Priorities ...........7 Rich Millet, Sujan Punyamurthula, Derek Morley and Loren Murray, URS Corporation Probabilistic Evaluation of Levee Distress for the Sacramento River Bank Protection Project .....................................9 Khaled Chowdhury, URS Corporation; Derek Morley and Mary Perlea, Corps of Engineers; Wilbur Huang, California Department of Water Resources; and Matthew Weil and Saritha Aella, URS Corporation Integrating Levee Performance Assessments into Complex Flood Protection Systems ..........................................11 T. Mitchell, -

(“PEA”) for the Production of High- Grade Nickel Concentrate from the Turnagain Nickel Deposit

October 28, 2020 TSX.V – GIGA Giga Metals Corporation Announces Results of a Comprehensive Preliminary Economic Assessment (“PEA”) for the Production of High- grade Nickel Concentrate from the Turnagain Nickel Deposit Vancouver, B.C. – Giga Metals Corp. (TSX VENTURE: GIGA) ( “Giga Metals” or the “Company”) today announced the results of a preliminary economic assessment (“PEA”) prepared in accordance with National Instrument 43-101 (“NI 43-101”) for the Turnagain Nickel-Cobalt Project (“Turnagain”) located 65 km east of Dease Lake in British Columbia, Canada. The PEA is an update of the 2011 PEA confirming the ability of Turnagain to produce high-quality nickel concentrate, such as that needed to make pure nickel products for the electric vehicle (EV) market, in a socially and environmentally responsible manner. The PEA has been prepared by Hatch Ltd, a global engineering company with substantial expertise in the mining sector, with input from Hatch personnel and industry expert consultants including Wood Mackenzie (nickel and cobalt markets, smelter terms), Blue Coast Metallurgy (process design), Knight Piésold (tailings and water management), Kerr Wood Leidal (power supply and costs), and Kirkham Geosystems (resource model and estimates). Giga Metals’ primary driver for this update was to deliver a reliable and comprehensive PEA incorporating all project- related components for use for discussion with strategic investors, for targeting improvement opportunities, and to serve as a base for future engineering studies. Summary The PEA indicates a long-life, large-scale project. With a projected build capital of US$1.4B (Phase 1) and US$0.5B (Phase 2) including significant investment for a powerline delivering low-cost, clean, low-carbon power from BC Hydro (mainly hydroelectric), the projected capital intensity is US$51,500 per annual tonne nickel at full rates (years 6 to 20). -

Greenfield Mine Lifecycle Costs

Ministry of the Economy Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada Potash Mining Supply Chain Requirement Guide For Greenfield Mine Lifecycle Costs H341318-0000-00-236-0001 Rev. 0 September 14, 2012 Saskatchewan Ministry of the Economy - Potash Mining Supply Chain Requirement Guide Greenfield Mine Lifecycle Costs Project Report September 14, 2012 Saskatchewan Ministry of the Economy Potash Mining Supply Chain Requirement Guide DISTRIBUTION Greenfield Mine Lifecycle Costs Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 1 2. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Model Study Size .................................................................................................................................. 2 3.1 Current Canadian Potash Facilities and Operational Capacities ................................................. 3 3.2 Greenfield Facilities Under Construction in Canada in 2012 ........................................................ 3 3.3 Potential Entrants Into Potash Mining in Canada in 2012 ............................................................ 3 3.4 Companies Conducting Exploration Projects in Saskatchewan But Not Yet Under Construction in 2012 ..................................................................................................................... 4 3.5 Recommended Study Size .......................................................................................................... -

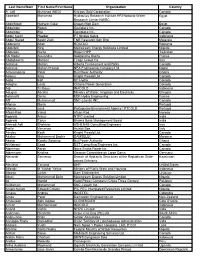

Participant List by Surname

Last Name/Nom First Name/First Name Organization Country A. Jalil Muhanad (NED) Kinross Gold Corporation Canada Abdellatif Mohamed Hydraulics Research Institute HRI National Water Egypt Research Center NWRC AbdelMoeti Hussein Galal Aswan High Dam Egypt Abdelnour Razek Geniglace Inc. Canada Abdelnour Elie Geniglace Inc. Canada Abdul Karim Haedar PT Nindya Karya Indonesia Abdul Razad Azwin Zailti TNB Research Sdn Bhd Malaysia Abdulamit Altan ROCOLD Romania Abdullahi Siraj Mainstream Energy Solutions Limited Nigeria Abduloev Nurilo Rogun HPP Tajikistan Abi Nader Alexandre Soletanche Bachy France Abolghasem Mohsen Tirage Group Co. Iran Acharya Mohan Alberta Environment and Parks Canada Acharya Mohan Prasad NEA Engineering Company Ltd. Nepal Acheampong Peter Bui Power Authority Ghana Adams Amy Knight Piesold Ltd. Canada Addo Kofi BC Hydro Canada Adeghe Louis Ontario Power Generation Canada Adji Tri Bayu INACOLD Indonesia Adugna Abraha Ministry of Water, Irrigation and Electricity Ethiopia Aelbrecht Denis EDF-Hydro Engineering France Afif Muhammad SNC-Lavalin INC. Canada Afonso Maria Portugal Afonso José Portuguese Environment Agency / PTCOLD Portugal Afsari-Rad Vahid Afsari-Rad Norway Agarwal Ankur NTPC Limited India Agarwal Tarun Bhakra Beas Management Board India Ahmadi Adli Shahryar ASHENAB Consulting Engineers Iran Aiello Vincenzo Astaldi Spa Italy Ainsley Keith Knight Piesold Ltd. Canada Akalay Mohammed Bachir DAMSELEC Morocco Akosa Kwaku Sarpong Bui Power Authority Ghana Al Katranji Saad DST Consulting Engineers Inc. Canada Alderman Aaron Nova Scotia Power Inc. Canada Aldermann Kristina German Committee on Large Dams Germany Alexandr Semenov Branch of Hydraulic Structures of the Republican State- Kazakstan owned Enterpris Alexieva Tatyana BHP United States Alfarobi M Yushar Yahya Ministry of Public Work and Housing Indonesia Algorta Javier Dam Engineering Uruguay Alhaji Mohammed Bello Mainstream Energy Solution Limited Nigeria Ali Hamid Karot Power Company (China Three Gorges) Pakistan Al-Mamun Mohammad SNC-Lavalin Inc. -

A New Era for Oil &

Oil & Gas 2 | Oil & Gas | Energy A new era for oil & gas Across the globe, demand for oil and gas continues to grow. At the same time, the industry is realizing it must come to terms with new pricing levels, ever-increasing environmental consciousness, and a shift to producing less carbon intensive forms of energy. Today, companies like yours are focused on sector transition to more flexible, lower carbon the bottom line. Conventional oil and gas generation. Interest in gas monetization developments are seeking to extract maximum opportunities, like gas-to-liquids (GTL) and value out of existing facilities and for new liquefied natural gas (LNG) is strongly gaining investments. They’re looking to reduce capital interest as a transportation fuel. expenditures by shaving down the size of their projects and rolling them out in phases. To thrive in this complex, shifting environment, you need your projects to become leaner, Unconventional sources of supply are also smarter, and simpler. They need to be better evolving. Heavy oil, tight oil and gas, oil sands, executed—more quickly and efficiently. That oil shale, waste, and biomass are all being means utilizing strategies and innovations that investigated, pursued, and perfected where the cut capital outlays and operating costs without economic and strategic conditions are right. compromising the integrity of your operation. Hydrocarbons, both oil and gas, are being found You need innovative solutions, in-depth industry in new areas. More pipelines, rail, and marine knowledge, and new technologies that can infrastructure are needed to transport it. reduce capital intensity and your environmental footprint. -

Nuclear Power Brochure.Pdf

Nuclear Power 2 | Energy | Nuclear Power It’s a nuclear world Everywhere, nuclear power is experiencing a renaissance. Reactors are being built in Finland, France, the United Kingdom, and China, with plans for many more. In Canada, the United States, and Argentina, major refurbishment programs are under way to safely prolong the life of units. Building, operating, and maintaining nuclear It’s labor intensive. The facilities must be power facilities efficiently and reliably is no easy meticulously maintained, and nuclear waste feat. You need a partner who understands the products must be dealt with. Expertly, safely, industry and who’s experienced with supporting and effectively. your ongoing operations, refurbishments, new builds, and waste management. One who For decades, we’ve worked with organizations can help you meet due diligence requirements like yours in North America and abroad. We and comply with regulations, licensing, and know the full nuclear fuel cycle and scope, from safety legislation. One with strong connections cradle to grave. We have the experience and to the procurement pipeline, who’s able to the bench strength to provide you with the very provide all the ongoing maintenance services best in nuclear power-and-energy engineering, that your facilities need. planning, and management consulting services. Nuclear technology offers safe, clean, low-cost Big. Small. New. Refurbished. Whatever your electrical power. But building the reactors, plans, whatever your scope. staffing them with capable, qualified personnel, We can help. and meeting regulatory requirements is complex. 3 Uranium processing Regulatory requirements, Value can be enhanced when you work with a codes, and standards team that’s experienced in the entire nuclear The world’s nuclear regulatory environment is fuel cycle. -

2016 Delegate List

2016 Delegate List Job Title Company Country Trader 9 Plus Resource LTD China Sales Support Manager ABB United Kingdom Group Account Executive ABB South Africa Head of Product Management and R&D ABB Switzerland Group Account Manager ABB Azerbaijan General Manager Pulp, Paper, Metals, Cement and Mining – South America ABB Ltda Brazil Country Manager of ABB in Chile ABB S.A. Chile Country Managing Director Peru ABB S.A. Peru Local Business Unit Manager ABB S.A. Chile Strategic Account Manager ABB SA Chile Product Group Manager Grinding – Chile ABB Switzerland Ltd Switzerland Area Sales Manager South America – Grinding ABB Switzerland Ltd Switzerland Regional Manager Americas – Minerals Processing ABB Switzerland Ltd Switzerland Head of Sales – Minerals Processing ABB Switzerland Ltd Switzerland Chief Technology Officer, Process Automation ABB Switzerland Ltd Switzerland Global Product Group Manager – Grinding & Material Handling ABB Switzerland Ltd Switzerland Vice President ABB Switzerland Ltd Switzerland Strategic Accounts Manager ABB Switzerland Ltd Switzerland Sales Manager WLAM Aggreko Chile Ing. Civil Industrial Aggreko Chile Metals Marketing Director Air Liquide France Commercial Director, Air Liquide Chile Air Liquide France Commercial Director, Air Liquide Global E&C Solutions France S.A. Air Liquide France AkzoNobel Functional Account Manager Chemicals S.A. Netherlands Director Business Allgemeine Gold- und Development & Marketing Silberscheideanstalt AG Germany ALTAMIRA Area Manager South America INFORMATION Spain President & CEO Alturas Minerals Corp Chile Business Development Manager Alxar Minería Chile CEO Alxar Minería Chile Geology Manager Alxar Minería Chile CEO Sierra Norte Alxar Minería Chile Project Engineer Alxar Minería Chile Amec Foster Wheeler International Ingeniería y Director of Operations Construcción Limitada Chile Amec Foster Wheeler Business Development International Ingeniería y Manager Construcción Ltda. -

Galaxy Sal De Vida Definitive Feasibility Study Update

ASX ANNOUNCEMENT / MEDIA RELEASE meeting a lithium future Perth, Western Australia 13 September 2012 GALAXY SAL DE VIDA DEFINITIVE FEASIBILITY STUDY UPDATE Highlights DFS anticipated to be completed in Q1 2013 Sal de Vida team boosted following key lithium expert appointments including industry veteran Dr Vijay Mehta as Senior Technical Advisor Sal de Vida team highly qualified in lithium brine operations Galaxy Resources Ltd (ASX: GXY) (“Galaxy” or “the Company”) advises that the Definitive Feasibility Study (“DFS”) being undertaken on its Sal de Vida lithium and potash brine project (“Sal de Vida” or “the Project”) in Argentina is progressing well and is expected to be completed in Q1 2013. Galaxy acquired a 70% stake in the Sal de Vida project following its merger with Lithium One Inc., which was completed in July 2012. Argentinean engineering firm TAGING S.A. (“TAGING”), which specialises in Argentinian mining projects with extensive experience in lithium brine projects, has been appointed to complete the DFS. International engineering company Hatch Ltd (“Hatch”) is providing specialist process input for Galaxy during the DFS process. Hatch was the designer and EPCM contractor for Galaxy’s Jiangsu Lithium Carbonate Plant (“Jiangsu”) in China and also has extensive lithium brine and operational experience in South America. A number of lithium experts to bolster the existing Sal de Vida project team have also been appointed. Most notable is the appointment of lithium industry veteran Dr Vijay Mehta as Senior Technical Advisor. Dr Mehta has 45+ years of experience in brine based lithium processing technology, including 30 years at FMC Lithium, where he developed the lithium plant at FMC’s Hombre Muerto Salar project, which adjoins Sal de Vida.