Conservation Implications When the Nest Predators Are Known

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Structure Use and Function of Song Categories in Brewer's Sparrows (Spizella Breweri)

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2000 Structure use and function of song categories in Brewer's sparrows (Spizella breweri) Brett L. Walker The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Walker, Brett L., "Structure use and function of song categories in Brewer's sparrows (Spizella breweri)" (2000). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6554. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6554 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission x: No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature: ----- Date :______ i'L/l%j(X>_____________ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE STRUCTURE, USE, AND FUNCTION OF SONG CATEGORIES IN BREWER'S SPARROWS {SPIZELLA BREWERI) by Brett L. -

Plum Tree Island National Wildlife Refuge Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Assessment January 2017 Front Cover: Salt Marsh Jeff Brewer/USACE

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Plum Tree Island National Wildlife Refuge Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Assessment January 2017 Front cover: Salt marsh Jeff Brewer/USACE This blue goose, designed by J.N. “Ding” Darling, has become the symbol of the National Wildlife Refuge System. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is the principal Federal agency responsible for conserving, protecting, and enhancing fish, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. The Service manages the National Wildlife Refuge System comprised of over 150 million acres including over 560 national wildlife refuges and thousands of waterfowl production areas. The Service also operates 70 national fish hatcheries and over 80 ecological services field stations. The agency enforces Federal wildlife laws, manages migratory bird populations, restores nationally significant fisheries, conserves and restores wildlife habitat such as wetlands, administers the Endangered Species Act, and helps foreign governments with their conservation efforts. It also oversees the Federal Assistance Program which distributes hundreds of millions of dollars in excise taxes on fishing and hunting equipment to state wildlife agencies. Comprehensive Conservation Plans (CCPs) provide long-term guidance for management decisions on a refuge and set forth goals, objectives, and strategies needed to accomplish refuge purposes. CCPs also identify the Service’s best estimate of future needs. These plans detail program levels that are sometimes substantially above current budget allocations and, as such, are primarily for Service strategic planning and program prioritization purposes. CCPs do not constitute a commitment for staffing increases, operational and maintenance increases, or funding for future land acquisition. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

Fall 2017 Maryland Birdlife Volume 66, Number 2

Fall 2017 Maryland Birdlife Volume 66, Number 2 Maryland Birdlife 66(2):29–35 First Known Case of a Passerine Presumably Returning a Dead Chick to the Nest Maren E. Gimpel1, 3 and Jennie M. Carr2 1Chester River Field Research Station, Washington College, 210 South Cross Street, Chestertown, Maryland 21620 USA 2Department of Biology, Washington College, 300 Washington Avenue, Chestertown, Maryland 21620 USA 3Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Nest sanitation is a well-documented behavior in birds, with benefits including less damage to eggs and chicks, lowering the risk of infection/infestation, and reduced nest detection by predators. Despite these clear benefits, here we report the first known documented case of a dead chick being placed back into a nest, presumably by a parent. We documented this behavior in a Field Sparrow (Spizella pusilla) as an incidental behavior observed as part of a larger multi-year provisioning study. Although the motivation behind returning a dead chick to a nest remains unclear, this is the first known reported case of such a behavior in any bird species. Keywords: behavior, dead nestling, Field Sparrow, nestling, nest sanitation, Spizella pusilla Many species of passerines engage in a variety of nest sanitation practices. Guigueno and Sealy (2012) reported 274 species of 40 families that engaged in some form of nest sanitation including the removal of debris such as twigs or other vegetation, foreign non-egg-shaped objects, cracked or broken eggs, unhatched eggs, egg shells, fecal sacs, and dead chicks. A clean nest may reduce parasitic infestations and olfaction- or vision-based detection by predators (Tinbergen et al. -

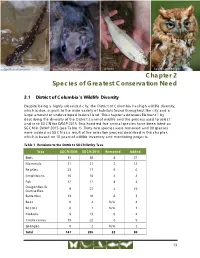

Chapter 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need

Spotted salamander Southern flying squirrel Alewife Eastern screech owl Chapter 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need 2.1 District of Columbia’s Wildlife Diversity Despite being a highly urbanized city, the District of Columbia has high wildlife diversity, which is due, in part, to the wide variety of habitats found throughout the city and a large amount of undeveloped federal land. This chapter addresses Element 1 by describing the diversity of the District’s animal wildlife and the process used to select and rank SGCN for SWAP 2015. Two hundred five animal species have been listed as SGCN in SWAP 2015 (see Table 1). Thirty-two species were removed and 90 species were added as SGCN as a result of the selection process described in this chapter, which is based on 10 years of wildlife inventory and monitoring projects. Table 1 Revisions to the District’s SGCN list by Taxa Taxa SGCN 2005 SGCN 2015 Removed Added Birds 35 58 4 27 Mammals 11 21 2 12 Reptiles 23 17 6 0 Amphibians 16 18 2 4 Fish 12 12 4 4 Dragonflies & 9 27 2 19 Damselflies Butterflies 13 10 6 3 Bees 0 4 N/A 4 Beetles 0 1 N/A 1 Mollusks 9 13 0 4 Crustaceans 19 22 6 9 Sponges 0 2 N/A 2 Total 147 205 32 90 13 Chapter 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need 2.1.1 Terrestrial Wildlife Diversity The District has a substantial number of terrestrial animal species, and diverse natural communities provide an extensive variety of habitat settings for wildlife. -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

East Fort Madison – Manhattan 22” Pipeline Inspections Sites 2015-065 and 2015-066 in Kankakee River

East Fort Madison – Manhattan 22” Pipeline Inspections Sites 2015-065 and 2015-066 in Kankakee River Illinois Department of Natural Resources CONSERVATION PLAN (Revised 3/15/ 17) (Application for an Incidental Take Authorization) Per 520ILCS 10/5.5 and 17 Ill. Adm. Code 1080 150-day minimum required for public review, biological and legal analysis, and permitting Project Applicant: BP US Pipelines & Logistics, 8230 Whitcomb St., Merrillville, IN 46410 Project Name: East Fort Madison – Manhattan 22” Pipeline Inspections Sites 2015-065 and 2015- 066 in Kankakee River County: Will County, Illinois Amount of Impact Area: 20,365ft2 (0.47 acres) below OHWM of Kankakee River Excavation within existing ROW – approximately 0.07 acres Staging – approximately 0.46 acres Access – approximately 0.99 acres 1. A description of the impact likely to result from the proposed taking of the species that would be covered by the authorization, including but not limited to: A. Identification of the area to be affected by the proposed action, includes a legal description and a detailed description including: street address, map(s), and GIS shapefile. Include an indication of ownership or control of affected property. Attach photos of the project area. BP U.S. Pipelines & Logistics (BP) must perform a physical inspection and possible repair of two (2) segments of their No. 1 System, 0.56m (22in) East Fort Madison – Manhattan pipeline within the Kankakee River in Will County, IL (Figure 2.0a). They are referenced as Sites 2015-065 and 2015-066 (“west” and “east” sites, respectively, Figure 2.0b). The project is located within a reach of the Kankakee River located in Will County, Illinois, in Section 22, Township 33N, R9E. -

Population Structure and Gene Flow in the Chipping Sparrow and a Hypothesis for Evolution in the Genus Spizella

Wilson Bull., 105(3), 1993, pp. 399-413 POPULATION STRUCTURE AND GENE FLOW IN THE CHIPPING SPARROW AND A HYPOTHESIS FOR EVOLUTION IN THE GENUS SPIZELLA ROBERT M. ZINK’ AND DONNA L. DITTMANN’ AssTnAcr.-We studied restriction site variation in the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of 55 Chipping Sparrows (Spizella passerina) taken from widely dispersed points in their breeding range. A total of 2 1 haplotypes was observed, and on average, individuals differed little in percent haplotype divergence (0.12%). There was no detectable geographic variation in haplotypes, despite the sampling of three named subspecies. Single-generation dispersal distance was estimated from the mtDNA data at 5.4 km. One phylogenetic hypothesis for six species in the genus (excluding Timberline Sparrow [S. taverneri] and Worthen’s Sparrow [S. worthenl]) suggested that Black-chinned Sparrow (S. atroguluris) and Field Sparrow (S. pusilla) were sister taxa, followed in sequence by Chipping, Brewer’s and Clay-colored sparrows (S. pallida), with the American Tree Sparrow (S. arboreu) most distant. Another hypothesis grouped Chipping and Brewer’s sparrows. Received 24 Aug. 1992, accepted 3 Feb. 1993. An important step in the evolutionary process is the origin of geographic patterns of genetic variation. Patterns of genetic variation form the basis for inferences about evolutionary processes that lead to the origin and maintenance of geographic variation and speciation. In the last 20 years, a number of molecular techniques, including protein electrophoresis and restriction site analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA; Avise et al. 1987), have been used to describe genetic variation within and among avian populations. For north temperate birds, protein electrophoresis revealed few alleles that varied geographically (Barrowclough 1983). -

Report on the Current Conditions for the Saltmarsh Sparrow (Ammospiza Caudacuta)

Report on the Current Conditions for the Saltmarsh Sparrow (Ammospiza caudacuta) U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service August 2020 1 Suggested citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2020. Report on the current conditions for the saltmarsh sparrow. August 2020. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Northeast Region, Charlestown, RI. 106 pp. Cover: Saltmarsh Sparrow (photo credit: Evan Lipton) 2 Executive Summary This report describes the species needs, threats, and current conditions for the saltmarsh sparrow. It is intended to reinforce and support conservation planning for this species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) and partners. As conservation measures are tested and implemented, the Service intends to expand this report to include an assessment of future conditions that reflects the effectiveness of on-the-ground implementation measures to slow or reverse saltmarsh sparrow population declines. The saltmarsh sparrow (Ammospiza caudacuta) is a tidal marsh obligate songbird that occurs exclusively in salt marshes along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States. Its breeding range extends from Maine to Virginia including portions of 10 states. The wintering range includes some of the southern breeding states and extends as far south as Florida. Nests are constructed in the salt marsh grasses just above the mean high water level, and they require a minimum of a 23-day period where the tides do not reach a height that causes nest failure. Across its range, the saltmarsh sparrow is experiencing low reproductive success, due primarily to nest flooding and predation, resulting in rapid population declines. Forty-eight percent of nests across the breeding range failed to produce a single nestling from 2011 to 2015. -

Nesting Success and Population Densities of Grassland Birds in the Breeding and Wintering Seasons in Tennessee and Kentucky

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2008 Nesting Success and Population Densities of Grassland Birds in the Breeding and Wintering Seasons in Tennessee and Kentucky Daniel Matthew Hinnebusch University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Hinnebusch, Daniel Matthew, "Nesting Success and Population Densities of Grassland Birds in the Breeding and Wintering Seasons in Tennessee and Kentucky. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2008. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3629 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Daniel Matthew Hinnebusch entitled "Nesting Success and Population Densities of Grassland Birds in the Breeding and Wintering Seasons in Tennessee and Kentucky." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Wildlife and Fisheries Science. David A. Buehler, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: