Sleep-Disordered Breathing Affects Auditory Processing in 5•Fi7 Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physiology of Basal Ganglia Disorders: an Overview

LE JOURNAL CANADIEN DES SCIENCES NEUROLOGIQUES SILVERSIDES LECTURE Physiology of Basal Ganglia Disorders: An Overview Mark Hallett ABSTRACT: The pathophysiology of the movement disorders arising from basal ganglia disorders has been uncer tain, in part because of a lack of a good theory of how the basal ganglia contribute to normal voluntary movement. An hypothesis for basal ganglia function is proposed here based on recent advances in anatomy and physiology. Briefly, the model proposes that the purpose of the basal ganglia circuits is to select and inhibit specific motor synergies to carry out a desired action. The direct pathway is to select and the indirect pathway is to inhibit these synergies. The clinical and physiological features of Parkinson's disease, L-DOPA dyskinesias, Huntington's disease, dystonia and tic are reviewed. An explanation of these features is put forward based upon the model. RESUME: La physiologie des affections du noyau lenticulaire, du noyau caude, de I'avant-mur et du noyau amygdalien. La pathophysiologie des desordres du mouvement resultant d'affections du noyau lenticulaire, du noyau caude, de l'avant-mur et du noyau amygdalien est demeuree incertaine, en partie parce qu'il n'existe pas de bonne theorie expliquant le role de ces structures anatomiques dans le controle du mouvement volontaire normal. Nous proposons ici une hypothese sur leur fonction basee sur des progres recents en anatomie et en physiologie. En resume, le modele pro pose que leurs circuits ont pour fonction de selectionner et d'inhiber des synergies motrices specifiques pour ex£cuter Taction desiree. La voie directe est de selectionner et la voie indirecte est d'inhiber ces synergies. -

Clinical Rating Scale for Pantothenate Kinase-Associated Neurodegeneration: a Pilot Study

RESEARCH ARTICLE Clinical Rating Scale for Pantothenate Kinase-Associated Neurodegeneration: A Pilot Study Alejandra Darling, MD,1 Cristina Tello, PhD,2 Marı´a Josep Martı´, MD, PhD,3 Cristina Garrido, MD,4 Sergio Aguilera-Albesa, MD, PhD,5 Miguel Tomas Vila, MD,6 Itziar Gaston, MD,7 Marcos Madruga, MD,8 Luis Gonzalez Gutierrez, MD,9 Julio Ramos Lizana, MD,10 Montserrat Pujol, MD,11 Tania Gavilan Iglesias, MD,12 Kylee Tustin,13 Jean Pierre Lin, MD, PhD,13 Giovanna Zorzi, MD, PhD,14 Nardo Nardocci, MD, PhD,14 Loreto Martorell, PhD,15 Gustavo Lorenzo Sanz, MD,16 Fuencisla Gutierrez, MD,17 Pedro J. Garcı´a, MD,18 Lidia Vela, MD,19 Carlos Hernandez Lahoz, MD,20 Juan Darı´o Ortigoza Escobar, MD,1 Laura Martı´ Sanchez, 1 Fradique Moreira, MD ,21 Miguel Coelho, MD,22 Leonor Correia Guedes,23 Ana Castro Caldas, MD,24 Joaquim Ferreira, MD,22,23 Paula Pires, MD,24 Cristina Costa, MD,25 Paulo Rego, MD,26 Marina Magalhaes,~ MD,27 Marı´a Stamelou, MD,28,29 Daniel Cuadras Palleja, MD,30 Carmen Rodrı´guez-Blazquez, PhD,31 Pablo Martı´nez-Martı´n, MD, PhD,31 Vincenzo Lupo, PhD,2 Leonidas Stefanis, MD,28 Roser Pons, MD,32 Carmen Espinos, PhD,2 Teresa Temudo, MD, PhD,4 and Belen Perez Duenas,~ MD, PhD1,33* 1Unit of Pediatric Movement Disorders, Hospital Sant Joan de Deu, Barcelona, Spain 2Unit of Genetics and Genomics of Neuromuscular and Neurodegenerative Disorders, Centro de Investigacion Prı´ncipe Felipe, Valencia, Spain 3Neurology Department, Hospital Clı´nic de Barcelona, Institut d’Investigacions Biomediques IDIBAPS. -

Radiologic-Clinical Correlation Hemiballismus

Radiologic-Clinical Correlation Hemiballismus James M. Provenzale and Michael A. Schwarzschild From the Departments of Radiology (J.M.P.), Duke University Medical Center, Durham, and f'leurology (M.A.S.), Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston Clinical History derived from the Greek word meaning "to A 65-year-old recently retired surgeon in throw," because the typical involuntary good health developed disinhibited behavior movements of the affected limbs resemble over the course of a few months, followed by the motions of throwing ( 1) . Such move onset of unintentional, forceful flinging move ments usually involve one side of the body ments of his right arm and leg. Magnetic res (hemiballismus) but may involve one ex onance imaging demonstrated a 1-cm rim tremity (monoballism), both legs (parabal enhancing mass in the left subthalamic lism), or all the extremities (biballism) (2, 3). region, which was of high signal intensity on The motions are centered around the shoul T2-weighted images (Figs 1A-E). Positive der and hip joints and have a forceful, flinging serum human immunodeficiency virus anti quality. Usually either the arm or the leg is gen and antibody titers were found, with predominantly involved. Although at least mildly elevated cerebrospinal fluid toxo some volitional control over the affected plasma titers. Anti-toxoplasmosis treatment limbs is still maintained, the involuntary with sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine was be movements typically can be checked by the gun, with resolution of the hemiballistic patient for only a few moments ( 1). The movements within a few weeks and decrease movements are usually continuous but may in size of the lesion. -

Movement Disorders Program & the Murray Center for Research on Parkinson's Disease & Related Disorders

Movement Disorders Medical University of South Carolina MUSC Health Movement DisordersMovement Disorders Program Program Program & The Murray 96 Jonathan Lucas Street, and the Murray Center for Research on Parkinson’sSuite Disease 301 CSB, MSC and 606 Related Disorders Center for Research on Charleston, SC 29425 Parkinson’s Disease & Related Disorders muschealth.org 843-792-3221 Changing What’s Possible “Our focus is providing patients with the best care possible, from treatment options to the latest technology and research. We have an amazing team of experts that provides compassionate care to each individual that we see.” — Dr. Vanessa Hinson Getting help from the MUSC Health Movement Disorders Program Millions of Americans suffer from movement disorders. These are typically characterized by involuntary movements, shaking, slowness of movement, or uncontrollable muscle contractions. As a result, day to day activities like walking, dressing, dining, or writing can become challenging. The MUSC Health Movement Disorders Program offers a comprehensive range of services, from diagnostic testing and innovative treatments to rehabilitation and follow-up support. Our team understands that Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders can significantly impact quality of life. Our goal is to provide you and your family continuity of care with empathy and compassion throughout the treatment experience. Please use this guide to learn more about Diseases Treated – information about the disorders and symptoms you might feel Specialty Procedures – treatments that show significant improvement for many patients Research – opportunities to participate in clinical trials at the MUSC Health Movement Disorders Program Profiles – MUSC Health movement disorder specialists We are dedicated to finding the cure for disabling movement disorders and to help bring about new treatments that can improve our patients’ lives. -

Hunting Down a Case of Progressive Movement Disorder, Dementia, and Genetic Anticipation – a Case Report on Huntington’S Disease

Madhavi et al (2020): r A case report of Huntington’s disease Nov 2020 Vol. 23 Issue 21 HUNTING DOWN A CASE OF PROGRESSIVE MOVEMENT DISORDER, DEMENTIA, AND GENETIC ANTICIPATION – A CASE REPORT ON HUNTINGTON’S DISEASE 1*Dr. K.Vani Madhavi, 2Dr. Anand Acharya, 3Dr Vijaya Vishnu 1,3Department of SPM, 2Department of Pharmacology , 1,2,3Konaseema Institute of medical Sciences Research Foundation, Amalapuram, Andhra Pradesh, India *corresponding author: 1Dr. K.Vani Madhavi E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract The Huntington Disease HD is a progressive, fatal, highly penetrant autosomal dominant disease considered by involuntary choreiform movements. A developing number of reformists generative conditions mirror the introduction of Huntington's ailment (HD). Separating between these HD-like conditions is vital once a patient by blend of development problems, psychological decrease, social irregularities and infection course demonstrates negative to the hereditary testing for HD causative transformations, that is, IT15 quality trinucleotide-rehash extension. The disparity finding of HD-like conditions is intricate and might prompt superfluous and exorbitant examinations. We suggest guidelines for this differential determination zeroing in on a predetermined number of clinical highlights ('warnings') that can be distinguished over precise clinical assessment, assortment of recorded information and a couple of routine auxiliary examinations. Present highlights incorporate the traditional foundation of the patient, the contribution of the facio-bucco-lingual and cervical region with development problem, the co-event of cerebellar highlights and seizures, the occurrence of exceptional stride examples and eye development irregularities, and an atypical movement of ailment. Extra assistance may get from the intellectual social introduction of the patient, just as by a limited amount of subordinate examinations, chiefly MRI and routine blood tests. -

Differential Changes in Arteriolar Cerebral Blood Volume Between Parkinson's Disease Patients with Normal and Impaired Cogniti

RESEARCH ARTICLE Differential Changes in Arteriolar Cerebral Blood Volume between Parkinson’s Disease Patients with Normal and Impaired Cognition and Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) Patients without Movement Disorder – An Exploratory Study Adrian G. Paez1,2, Chunming Gu1,2,3, Suraj Rajan4,5, Xinyuan Miao1,2, Di Cao1,2,3, Vidyulata Kamath5, Arnold Bakker5, Paul G. Unschuld6, Alexander Y. Pantelyat4, Liana S. Rosenthal4, and Jun Hua1,2 1F.M. Kirby Research Center for Functional Brain Imaging, Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, MD; 2Neurosection, Division of MR Research, Department of Radiology, 3Department of Biomedical Engineering; 4Department of Neurology; and 5Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD; and 6Department of Psychogeriatric Medicine, Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Corresponding Author: Key Words: Dementia, blood vessel, perfusion, iVASO, MRI Jun Hua, PhD Abbreviations: Parkinson’s disease (PD), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), arteriolar Department of Radiology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, cerebral blood volume (CBVa), PD dementia (PDD), cerebral blood flow (CBF), F.M. Kirby Research Center for Functional Brain Imaging, Kennedy presupplementary motor area (preSMA), inflow-based vascular-space-occupancy Krieger Institute, 707 N Broadway, Baltimore, MD, 21205, (iVASO), gray matter (GM), time of repetition (TR), time of inversion (TI), statistical E-mail: [email protected] parametric mapping (SPM), signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPRDS) Cognitive impairment amongst Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients is highly prevalent and associated with an increased risk of dementia. There is growing evidence that altered cerebrovascular functions contribute to cognitive impairment. -

The Clinical Approach to Movement Disorders Wilson F

REVIEWS The clinical approach to movement disorders Wilson F. Abdo, Bart P. C. van de Warrenburg, David J. Burn, Niall P. Quinn and Bastiaan R. Bloem Abstract | Movement disorders are commonly encountered in the clinic. In this Review, aimed at trainees and general neurologists, we provide a practical step-by-step approach to help clinicians in their ‘pattern recognition’ of movement disorders, as part of a process that ultimately leads to the diagnosis. The key to success is establishing the phenomenology of the clinical syndrome, which is determined from the specific combination of the dominant movement disorder, other abnormal movements in patients presenting with a mixed movement disorder, and a set of associated neurological and non-neurological abnormalities. Definition of the clinical syndrome in this manner should, in turn, result in a differential diagnosis. Sometimes, simple pattern recognition will suffice and lead directly to the diagnosis, but often ancillary investigations, guided by the dominant movement disorder, are required. We illustrate this diagnostic process for the most common types of movement disorder, namely, akinetic –rigid syndromes and the various types of hyperkinetic disorders (myoclonus, chorea, tics, dystonia and tremor). Abdo, W. F. et al. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 29–37 (2010); doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.196 1 Continuing Medical Education online 85 years. The prevalence of essential tremor—the most common form of tremor—is 4% in people aged over This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance 40 years, increasing to 14% in people over 65 years of with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council age.2,3 The prevalence of tics in school-age children and for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of 4 MedscapeCME and Nature Publishing Group. -

Stanford Movement Disorders Center

MEDICINE Stanford Movement Disorders Center The ability to move our bodies as we please is something most of us take for granted. Yet, for some people, the brain and the body are no longer in sync. Simple movements become difficult and/or unwanted movements interrupt the normal repertoire. Movement disorders occur when the circuitry within the sensorimotor network in the brain is not functioning correctly. With our aging population, it is expected that the prevalence of movement disorders in the United States will double by 2030. Still, with improved treatments and new research, there is reason to hope. Movement disorders can be difficult to diagnose and require an in-depth evaluation by a movement disorders specialist. The Stanford Movement Disorders Center provides comprehensive evaluations and care by a multispecialty team that works together to help maintain quality of life for people with movement disorders. Experts from neurosurgery, behavioral neurology, neuropsychology, sleep medicine, psychiatry, nuclear medicine, radiology, genetics, nursing, and pharmacy collaborate closely with our movement disorders neurologists to provide medical care that is both cutting edge and compassionate. Parkinson’s disease: Promising new methods for diagnosis and treatment Parkinson’s disease is a chronic neurological disorder and is the second most common neurodegenerative disease in America, after Alzheimer’s disease. There are many factors that may contribute to the development of Parkinson’s disease such as genetics, injury, environ- mental toxins, a vascular or metabolic disorder, or certain medications. Increasing age is one of the strongest factors. In the brain, nerve cells (neurons) normally secrete a chemical called dopamine that relays messages between certain parts of the brain, facilitating smooth, coordinated muscle movements. -

Physical and Occupational Therapy

Physical and Occupational Therapy Huntington’s Disease Family Guide Series Physical and Occupational Therapy Family Guide Series Reviewed by: Suzanne Imbriglio, PT Edited by Karen Tarapata Deb Lovecky HDSA Printing of this publication was made possible through an educational grant provided by The Bess Spiva Timmons Foundation Disclaimer Statements and opinions in this book are not necessarily those of the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, nor does HDSA promote, endorse, or recommend any treatment mentioned herein. The reader should consult a physician or other appropriate healthcare professional concerning any advice, treatment or therapy set forth in this book. © 2010, Huntington’s Disease Society of America All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any way without the expressed written permission of HDSA. Contents Introduction Movement Disorders in HD 4 Cognitive Disorders 8 The Movement Disorder and Nutrition 9 Physical Therapy in Early Stage HD Pre-Program Evaluation 11 General Physical Conditioning for Early Stage HD 14 Cognitive Functioning and Physical Therapy 16 Physical Therapy in Mid-Stage HD Assessment in Mid-Stage HD 17 Functional Strategies for Balance and Seating 19 Physical Therapy in Later Stage HD Restraints and Specialized Seating 23 Accommodating the Cognitive Disorder in Later Stage HD 24 Occupational Therapy in Early Stage HD Addressing the Cognitive Disability 26 Safety in the Home 28 Occupational Therapy in Mid-Stage HD Problems and Strategies 29 Occupational Therapy in Later Stage HD Contractures 33 Hope for the Future 34 Introduction Understanding Huntington’s Disease Huntington’s Disease (HD) is a hereditary neurological disorder that leads to severe physical and mental disabilities. -

Movement Disorders and AIDS: a Review

Parkinsonism and Related Disorders 10 (2004) 323–334 www.elsevier.com/locate/parkreldis Review Movement disorders and AIDS: a review Winona Tsea,*, Maria G. Cersosimob, Jean-Michel Graciesa, Susan Morgelloc, C. Warren Olanowa, William Kollera aDepartment of Neurology, Mount Sinai Medical Center, One Gustave L. Levy Place, Box 1052, New York, NY 10029, USA bDepartment of Neurology, University of Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina cDepartment of Pathology, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY, USA Abstract Movement disorders are a potential neurologic complication of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), and may sometimes represent the initial manifestation of HIV infection. Dopaminergic dysfunction and the predilection of HIV infection to affect subcortical structures are thought to underlie the development of movement disorders such as parkinsonism in AIDS patients. In this review, we will discuss the clinical presentations, etiology and treatment of the various AIDS-related hypokinetic and hyperkinetic movement disorders, such as parkinsonism, chorea, myoclonus and dystonia. This review will also summarize current concepts regarding the pathophysiology of parkinsonism in HIV infection. q 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Parkinsonism; AIDS; Human immunodeficiency virus; Movement disorders; Dopamine; Chorea Contents 1. Introduction............................................................................. 324 2. Tremor ................................................................................ 324 2.1. -

Movement Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases

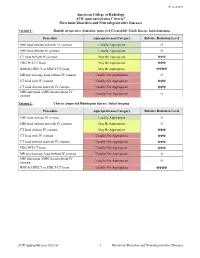

Revised 2019 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Movement Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases Variant 1: Rapidly progressive dementia; suspected Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level MRI head without and with IV contrast Usually Appropriate O MRI head without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O CT head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ FDG-PET/CT brain May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ HMPAO SPECT or SPECT/CT brain May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ MR spectroscopy head without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O CT head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ MRI functional (fMRI) head without IV Usually Not Appropriate O contrast Variant 2: Chorea; suspected Huntington disease. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level MRI head without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O MRI head without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate O CT head without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT head with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT head without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ FDG-PET/CT brain Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ MR spectroscopy head without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI functional (fMRI) head without IV Usually Not Appropriate O contrast HMPAO SPECT or SPECT/CT brain Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Movement Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases Variant 3: Parkinsonian syndromes. Initial -

MDS Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Parkinson's Disease

REVIEW CME MDS Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Parkinson’s Disease Ronald B. Postuma, MD, MSc,1†* Daniela Berg, MD,2†* Matthew Stern, MD,3 Werner Poewe, MD,4 C. Warren Olanow, MD, FRCPC,5 Wolfgang Oertel, MD,6 Jose Obeso, MD, PhD,7 Kenneth Marek, MD,8 Irene Litvan, MD,9 Anthony E. Lang, OC, MD, FRCPC,10 Glenda Halliday, PhD,12 Christopher G. Goetz, MD,13 Thomas Gasser, MD,2 Bruno Dubois, MD, PhD,14 Piu Chan, MD, PhD,15 Bastiaan R. Bloem, MD, PhD,16 Charles H. Adler, MD, PhD,17 and Gunther€ Deuschl, MD18 1Department of Neurology, Montreal General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 2Department of Neurodegeneration, Hertie-Institute for Clinical Brain Research and German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases, Tuebingen, Germany 3Penn Neurological Institute, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA 4Department of Neurology, Innsbruck Medical University, Innsbruck, Austria 5Department of Neurology, The Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, New York, USA 6Department of Neurology, Philipps University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany 7University of Navarra-FIMA, Pamplona, Spain 8Institute for Neurodegenerative Disorders, New Haven, Connecticut, USA 9Department of Neurosciences, UC San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA 10Division of Neurology, Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 12Neuroscience Research Australia & University of NSW, Randwick, Australia 13Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA 14Hopital De La Salpetriere, Paris, France 15Xuanwu Hospital of Capitol of Medical University, Beijing, Peoples Republic of China 16Department