View PDF of Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vice President in the U.S

The Vice President in the U.S. Senate: Examining the Consequences of Institutional Design Michael S. Lynch Anthony J. Madonna Asssistant Professor Assistant Professor University of Kansas University of Georgia [email protected] [email protected] September 3, 2010∗ ∗The authors would like to thank Scott H. Ainsworth, Stanley Bach, Richard A. Baker, Ryan Bakker, Richard S. Beth, Sarah A. Binder, Jamie L. Carson, Michael H. Crespin, Keith L. Dougherty, Trey Hood, Scott C. James, Andrew D. Martin, Ryan J. Owens, and Steven S. Smith for comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. Madonna also thanks the University of Georgia American Political Development working group for support and comments, and Rachel Snyder for helpful research assistance. All errors remain the authors. Abstract The constitutional placement of the vice president as the president of the Senate is a unique feature of the chamber. It places control over the Senate's rules and precedents under an individual who is not elected by the chamber and receives no direct benefits from the maintenance of its institutions. We argue that this feature has played an important role in the Senate's development. The vice president has frequently acted in a manner that conflicted with the wishes of chamber majorities. Consequently, senators have been reluctant to allow cham- ber power to be centralized under their largely unaccountable presiding officer. This fear has prevented the Senate from allowing its chair to reduce dilatory action, as the House has done. Accordingly, delay via the filibuster, has become commonplace in the Senate. Such delay has reduced the Senate's efficiency, but has largely freed it from the potential influence of the executive branch. -

FALCON V, LLC, Et Al.,1 DEBTORS. CASE NO. 19-10547 CHAPT

Case 19-10547 Doc 103 Filed 05/21/19 Entered 05/21/19 08:56:32 Page 1 of 13 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA IN RE: CASE NO. 19-10547 FALCON V, L.L.C., et al.,1 CHAPTER 11 DEBTORS. (JOINTLY ADMINISTERED) ORDER APPROVING FALCON V, L.L.C.'S ACQUISITION OF ANADARKO E&P ONSHORE LLC’S INTEREST IN CERTAIN OIL, GAS AND MINERAL INTERESTS Considering the motion of the debtors-in-possession, Falcon V, L.L.C., (“Falcon”) for an order authorizing Falcon’s acquisition of the interest of Anadarko E&P Onshore LLC (“Anadarko”) in certain oil, gas and mineral leases (P-13), the evidence admitted and argument of counsel at a May 14, 2019 hearing, the record of the case and applicable law, IT IS ORDERED that the Debtors are authorized to take all actions necessary to consummate the March 1, 2019 Partial Assignment of Oil, Gas and Mineral Leases (the “Assignment”) by which Anadarko agreed to assign its right, title and interest in and to certain oil, gas and mineral leases in the Port Hudson Field, including the Letter Agreement between Falcon and Anadarko attached to this order as Exhibit 1. IT IS FURTHERED ORDERED that notwithstanding anything to the contrary in this order, the relief granted in this order and any payment to be made hereunder shall be subject to the terms of this court's orders authorizing debtor-in-possession financing and/or granting the use of cash collateral in these chapter 11 cases (including with respect to any budgets governing or related to such use), and the terms of such financing and/or cash collateral orders shall control if 1 The Debtors and the last four digits of their respective taxpayer identification numbers are Falcon V, L.L.C. -

AMERIKA DIENST" Vom 1

"AMERIKA-DIENST U.S.Feature Service INKAJi3LSVr.R2,EI0ENIS ÜBER NAGHRIGJlTEIfoLVIERIAL UND ARTIKEL DES "AMERIKA DIENST" vom 1. April 1949 - >0. Juni 1949 Um Ihnen das'Auffinden von Nachrichten und Artikeln aus früheren Nummern des »AMERIKA DIENST." zu erleichtern, bringen wir Ihnen ein Inhaltsverzeich nis des Materials, das Ihnen im zweiten Quartal 1949 zugegangen ist. Durch eine Aufgliederang nach Sachge bieten soll Ihnen die spätere Verwendung des einen oder anderen nicht allzu zeitgebundenen Artikels ermöglicht werden. Redaktion »AMERIKA DIENST" (U.S. Feature Service). Redaktion: Bad Nauheim, Goethestrasse 4 (Tel. 2027/2209) I "AMERIKA-DIENST U.S. Feature Service INHALTSVERZEICHNIS ÜBER NACEP.IOHTEMMTE-RXAL UNL ARTIKEL DES "AMERIKA LIEHST" vom 1. April 1949 - 3°. Juni 1949 1) Amerikanische pressestimmen Seite 1 2] Leben in den U.o.A. n 4 ii 3 Wissenschaft 6 4 Portrait der Woche ii 6 5 Kunst ii 7 6 Musik it 7 Theater II 7 i Das neue Buch n 8 j: Europäisches Wiederaufbauprogramm II 8 109 Vereinte Nationen II 8 11 I Wirtschaft II 9 12 > Arbeit II 9 13 ) Sozialwesen II 9 M< \ Finanzwesen IT 9 15 ) Pariser Aussenministerkonferenz II 11 16 ) Politik II 10 17 ) Architektur II 10 18 1 Literatur II 10 19 \ Emigration II 11 20 | Erziehung II 11 21 1 Medizinische Forschung II 11 22 I Forstwirtschaft II 11 23 1 Luftbrücke II 11 24 J Flugwesen II 11 25 J Journalistik II 11 26 ) Handel und Industrie II 12 27 ) Religion II 12 28 ) Geschichte (Spezial) II 12 29 i Amerikanische Feiertage II 12 30 ) Meilensteine auf unserem Wege II 12 31 i Zu Ihrer Information II 12 32 ) Internationaler Handel II 13 33 ) Fernsehen II 13 34 ) Artikel für die Frau II 13 35 ) Kurznachrichten für die Frau 11 14 II 36 ) Erziehungswesen , 15 37 ) Medizinische Nachrichten II 16 38 ) Landwirtsc hat" bliche Nachrichten II 17 II 39 ) fU^nderuurruiiQrr) W + + -f 4 + + + •*• t + + + •+ + < + Redaktion: Bad Nauheim, Goethestrasse 4 (Tel. -

Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in Maryland

Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in Maryland Founding the Proprietary Colony The founding and establishment of the propriety government of Maryland was the product of competing factors—political, commercial, social, and religious. It was intertwined with the history of one family, the Calverts, who were well established among the Yorkshire gentry and whose Catholic sympathies were widely known. George Calvert had been a favorite of the Stuart king, James I. In 1625, following a noteworthy career in politics, including periods as clerk of the Privy Council, member of Parliament, special emissary abroad of the king, and a principal secretary of state, Calvert openly declared his Catholicism. This declaration closed any future possibility of public office for him. Shortly thereafter, James elevated Calvert to the Irish peerage as the baron of Baltimore. Calvert’s absence from public office afforded him an opportunity to pursue his interests in overseas colonization. Calvert appealed to Charles I, son of James, for a land grant.1 Calvert’s appeal was honored, but he did not live to see a charter issued. In 1632, Charles granted a proprietary charter to Cecil Calvert, George’s son and the second baron of Baltimore, making him Maryland’s first proprietor. Maryland’s charter was the first long-lasting one of its kind to be issued among the thirteen mainland British American colonies. Proprietorships represented a real share in the king’s authority. They extended unusual power. Maryland’s charter, which constituted Calvert and his heirs as “the true and absolute Lords and Proprietaries of the Region,” might have been “the best example of a sweeping grant of power to a proprietor.” Proprietors could award land grants, confer titles, and establish courts, which included the prerogative of hearing appeals. -

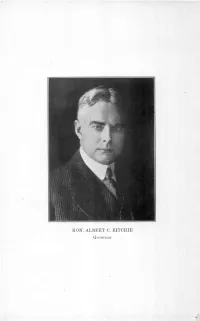

HON. ALBERT C. RITCHIE Governor -3-^3-/6" '' C ^ O 1 N J U

HON. ALBERT C. RITCHIE Governor -3-^3-/6" '' c ^ o 1 n J U MARYLAND MANUAL l 925 A Compendium of Legal, Historical and Statistical Information Relating to the STATE OF MARYLAND Compiled by E. BROOKE LEE, Secretary of State. 20TH CENTURY PRINTING CO. BALTIMORE. MD. State Government, 1925 EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT State House, Annapolis. Baltimore Office 603 Union Trust Building. (iovernor: Albert C. Ritchie Baltimore City Secretary of State: E. Brooke Lee Silver Spring Executive Secretary: Kenneth M. Burns. .Baltimore Stenographers: Miss Virginia Dinwiddie Ellinger ; Baltimore Mrs. Bettie Smith ...Baltimore Clerks: Murray G. Hooper Annapolis Raymond M. Lauer. — Annapolis Chas. Burton Woolley .Annapolis The Governor is elected by the people for a term of four years from the second Wednesday in January ensuing his election (Constitu- tion, Art. 2, Sec. 2) ;* The Secretary of State is appointed by the Gov- ernor, with the consent of the Senate, to hold office during the term of the Governor; all other officers are appointed by the Governor to hold office during his pleasure Under the State Reorganization Law, which became operative Janu- ary 1, 1923, the Executive Department was reorganized and enlarged to include, besides the Secretary of State, the following: Parole Commis- sioner, The Commissioner of the Land Office, The Superintendent of Pub- lic Buildings, The Department of Legislative Reference, The Commis- sioners for Uniform State Laws, The State Librarian. The Secretary of State, in addition to his statutory duties, is the General Secretary -

The Honorable Benjamin L. Cardin United States Senate 509 Hart

The Honorable Benjamin L. Cardin The Honorable Anthony Brown United States Senate U.S. House of Representatives 509 Hart Senate Office Building 1505 Longworth House Office Building Washington, D.C. 20510-2003 Washington, DC 20515 The Honorable Christopher Van Hollen, Jr. The Honorable Steny H. Hoyer United States Senate U.S. House of Representatives 110 Hart Senate Office Building Majority Leader Washington, D.C. 20510-2002 1705 Longworth House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 The Honorable Andrew P. Harris U.S. House of Representatives The Honorable David Trone 1533 Longworth House Office Building U.S. House of Representatives Washington, DC 20515 1213 Longworth House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 The Honorable C. A. Dutch Ruppersberger III U.S. House of Representatives The Honorable Jamie Raskin 2416 Rayburn House Office Building U.S. House of Representatives Washington, DC 20515 431 Cannon House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 The Honorable John P. Sarbanes U.S. House of Representatives 2444 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 April 16, 2020 RE: Joint Letter to Maryland’s Congressional Delegation Maryland Businesses and Bankers Urge Immediate New Funding for the Paycheck Protection Program and Action to Protect Businesses with Applications in Process Dear Maryland U.S. Senators and Representatives: We, the undersigned representing small businesses across Maryland, are writing to urge Maryland’s Congressional leaders to advocate for swift passage of the fourth COVID-19 stimulus package to ensure that the additional $250 billion in funding for the SBA’s Paycheck Protection Program is approved. In less than two weeks, the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) approved $350 billion in financial assistance to small businesses across Maryland and the U.S., helping those businesses maintain their employees and cover operating expenses during the COVID-19 emergency. -

2019 Session Maryland General Assembly This Document Was Prepared By

ROSTER LIST OF& COMMITTEES 2019 Session Maryland General Assembly This document was prepared by: Library and Information Services Office of Policy Analysis Department of Legislative Services General Assembly of Maryland April 29, 2019 For additional copies or further information, please contact: Library and Information Services 90 State Circle Annapolis, Maryland 21401-1991 Baltimore/Annapolis Area: 410-946-5400/5410 Washington Area: 301-970-5400/5410 Other Maryland Areas: 1-800-492-7122, ext. 5400/5410 TTY: 410-946/301-970-5401 TTY users may also use the Maryland Relay Service to contact the General Assembly. E-Mail: [email protected] Maryland General Assembly Web site: http://mgaleg.maryland.gov Department of Legislative Services Web site: http://dls.state.md.us The Department of Legislative Services does not discriminate on the basis of age, ancestry, color, creed, marital status, national origin, race, religion, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, or disability in the admission or access to its programs, services, or activities. The Department's Information Officer has been designated to coordinate compliance with the nondiscrimination requirements contained in Section 35.107 of the Department of Justice Regulations. Requests for assistance should be directed to the Information Officer at the telephone numbers shown above. ii Contents ....................................................................................................................................... Page Senate of Maryland Senate Biographies ............................................................................................................. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

The Vice President in the U.S. Senate: Examining the Consequences of Institutional Design

The Vice President in the U.S. Senate: Examining the Consequences of Institutional Design. Michael S. Lynch Tony Madonna Asssistant Professor Assistant Professor University of Kansas University of Georgia [email protected] [email protected] January 25, 2010∗ ∗The authors would like to thank Scott H. Ainsworth, Stanley Bach, Ryan Bakker, Sarah A. Binder, Jamie L. Carson, Michael H. Crespin, Keith L. Dougherty, Trey Hood, Andrew Martin, Ryan J. Owens and Steven S. Smith for comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. Madonna also thanks the University of Georgia American Political Development working group for support and comments, and Rachel Snyder for helpful research assistance. All errors remain the authors. Abstract The constitutional designation of the vice president as the president of the United States Senate is a unique feature of the chamber. It places control over the Senate's rules and precedents under an individual who is not elected by the chamber and receives no direct benefits from the maintenance of its institutions. We argue that this feature of the Senate has played an important, recurring role in its development. The vice president has frequently acted in a manner that conflicted with the wishes chamber majorities. Consequently, the Senate has developed rules and precedents that insulate the chamber from its presiding officer. These actions have made the Senate a less efficient chamber, but have largely freed it from the potential influence of the executive branch. We examine these arguments using a mix of historical and contemporary case studies, as well as empirical data on contentious rulings on questions of order. -

The Republican

mercenary element to effect and con- success of those who formerly were OUR WASHINGTON LETTER. Conk ling’s nomination to the Su- men ofthe same character. The fol- the government of our lair o|,j Whyte’s outspoken opponents preme Court was discussed here it THE REPUBLICAN. lowing Senators are said to hnvi uni .Mayor [From llegirktrCorrespor dent.] was urged that lie would never to rejeei Stale? slid whose elevation was ilie contin- our ac- -igned a written contract taking OAKLAND, : in power, the in office of men whom the peo- cept a position which would force MARYLAND- any nominee on the objection ot The party uance Washington. I). C., March 20,1882. of its own men, lias failed ple turned down when they elected him to walk behind all Hie "tilers of -ingle member of their syndicate; judgement Nothing appears more certain to lias failed to The work was dune, ibe same class on all occasions of Wells, Winfield, to fulfil its duty, eon. Mayor Whyte. of events than JAS. A. HAYDEN, . Messrs. Williams. Hie observers political that the greatest the was that the Mayor ceremony. Till* most recently ap- Hepron, Bians, Bond, Cooper; Gill. trol public affairs so and result that the Democratic politicians can Editor and Proprietor. number enini- poii tad Justice of Hie Supreme Court Getty, Vanderford, Parsons, Farrow, good of the greatest shall be incurred Governor Hamilton’* not, or will mt, learn anything—not become ty without gaming the friendship ol always walk behind the others Lancaster, Allston and Magruder. accomplished, has unsatisfac- even by experience. -

The World Almanac

• 181~ the prloee and force the aale 118 for the Treuur7 with the 1 t lldatratlOD of powen dlatrlbuted by potute, e ouet In &II. State of .w.YoJUt, where a Democratic majorltr of 110,000 WOR. The Democratic Hooae of eto of a BepubIlean te aDd a ~... the power to ne&ore proeperlty 01 the 01 for a peat party. To dlaeern a the !e8ODJ'CeII 01 a eompeteut and y to eep the tro t of a people' THEVWORLD ALMANAC FOR l!rbc'¥rar ISiS. TUB year,187S i~ the latter part of the s635t.h and t.he begillnln of the ~636th since the creation of the world. accordmg to the Jews. It answers to the 6588th ot9 the Julian Period, the 2628th from the foundation of Rome, the 2651Ht yem' of the Olympiads, and the yea.r 7383-84 of the Byzantine era. The looth year of Amedc;lJ~ Indcpenuence beginl! Jllly 4. ~be .fiour ';::'casons. D. H. M. D. H. M. Winter bewns, 1874. Decembcr 21. 6 14 el"f andJasts 89 0 S9 Spring , 1875, MarcIl 20, 7 13 ev., 92 20 26 Summer·" 1875, June' 21,339 ev., 93 1428 Autumn" 1875, September 23, 6 7 mo., 89 18 I Winter ".. "'IB75, December 22, 0 8 mo., Trop. year, ,365 5 54 Clt:onfunctfon of ~lanetst anlJ otb~ ~bcnomt1ta. -----------------_.__._------_._------------.,.-_._---;--'------ IMonth. Alpect. apart. I' Month.! Aspect. Washington Distance apart. I Wfts1~lnr;to.TIme. ! Dlstan~e , I Tim•• -------- D n X I G' 1--1 D.H.X. -

Catalogue of the Alumni of the University of Pennsylvania

^^^ _ M^ ^3 f37 CATALOGUE OF THE ALUMNI OF THE University of Pennsylvania, COMPRISING LISTS OF THE PROVOSTS, VICE-PROVOSTS, PROFESSORS, TUTORS, INSTRUCTORS, TRUSTEES, AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGIATE DEPARTMENTS, WITH A LIST OF THE RECIPIENTS OF HONORARY DEGREES. 1749-1877. J 3, J J 3 3 3 3 3 3 3', 3 3 J .333 3 ) -> ) 3 3 3 3 Prepared by a Committee of the Society of ths Alumni, PHILADELPHIA: COLLINS, PRINTER, 705 JAYNE STREET. 1877. \ .^^ ^ />( V k ^' Gift. Univ. Cinh il Fh''< :-,• oo Names printed in italics are those of clergymen. Names printed in small capitals are tliose of members of the bar. (Eng.) after a name signifies engineer. "When an honorary degree is followed by a date without the name of any college, it has been conferred by the University; when followed by neither date nor name of college, the source of the degree is unknown to the compilers. Professor, Tutor, Trustee, etc., not being followed by the name of any college, indicate position held in the University. N. B. TJiese explanations refer only to the lists of graduates. (iii) — ) COEEIGENDA. 1769 John Coxe, Judge U. S. District Court, should he President Judge, Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. 1784—Charles Goldsborough should he Charles W. Goldsborough, Governor of Maryland ; M. C. 1805-1817. 1833—William T. Otto should he William T. Otto. (h. Philadelphia, 1816. LL D. (of Indiana Univ.) ; Prof, of Law, Ind. Univ, ; Judge. Circuit Court, Indiana ; Assistant Secre- tary of the Interior; Arbitrator on part of the U. S. under the Convention with Spain, of Feb.