Collaborating with James Baldwin on a Screenplay of Giovanni's Room

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kam Williams, “The “12 Years a Slave” Interview: Steve Mcqueen”, the New Journal and Guide, February 03, 2014

Kam Williams, “The “12 Years a Slave” Interview: Steve McQueen”, The new journal and guide, February 03, 2014 Artist and filmmaker Steven Rodney McQueen was born in London on October 9, 1969. His critically-acclaimed directorial debut, Hunger, won the Camera d’Or at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival. He followed that up with the incendiary offering Shame, a well- received, thought-provoking drama about addiction and secrecy in the modern world. In 1996, McQueen was the recipient of an ICA Futures Award. A couple of years later, he won a DAAD artist’s scholarship to Berlin. Besides exhibiting at the ICA and at the Kunsthalle in Zürich, he also won the coveted Turner Prize. He has exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Documenta, and at the 53rd Venice Biennale as a representative of Great Britain. His artwork can be found in museum collections around the world like the Tate, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Centre Pompidou. In 2003, he was appointed Official War Artist for the Iraq War by the Imperial War Museum and he subsequently produced the poignant and controversial project Queen and Country commemorating the deaths of British soldiers who perished in the conflict by presenting their portraits as a sheet of stamps. Steve and his wife, cultural critic Bianca Stigter, live and work in Amsterdam which is where they are raising their son, Dexter, and daughter, Alex. Here, he talks about his latest film, 12 Years a Slave, which has been nominated for 9 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

Film Suggestions to Celebrate Black History

Aurora Film Circuit I do apologize that I do not have any Canadian Films listed but also wanted to provide a list of films selected by the National Film Board that portray the multi-layered lives of Canada’s diverse Black communities. Explore the NFB’s collection of films by distinguished Black filmmakers, creators, and allies. (Link below) Black Communities in Canada: A Rich History - NFB Film Info – data gathered from TIFF or IMBd AFC Input – Personal review of the film (Nelia Pacheco Chair/Programmer, AFC) Synopsis – this info was gathered from different sources such as; TIFF, IMBd, Film Reviews etc. FILM TITEL and INFO AFC Input SYNOPSIS FILM SUGGESTIONS TO CELEBRATE BLACK HISTORY MONTH SMALL AXE I am very biased towards the Director Small Axe is based on the real-life experiences of London's West Director: Steve McQueen Steve McQueen, his films are very Indian community and is set between 1969 and 1982 UK, 2020 personal and gorgeous to watch. I 1st – MANGROVE 2hr 7min: English cannot recommend this series Mangrove tells this true story of The Mangrove Nine, who 5 Part Series: ENOUGH, it was fantastic and the clashed with London police in 1970. The trial that followed was stories are a must see. After listening to the first judicial acknowledgment of behaviour motivated by Principal Cast: Gary Beadle, John Boyega, interviews/discussions with Steve racial hatred within the Metropolitan Police Sheyi Cole Kenyah Sandy, Amarah-Jae St. McQueen about this project you see his 2nd – LOVERS ROCK 1hr 10 min: Aubyn and many more.., A single evening at a house party in 1980s West London sets the passion and what this production meant to him, it is a series of “love letters” to his scene, developing intertwined relationships against a Category: TV Mini background of violence, romance and music. -

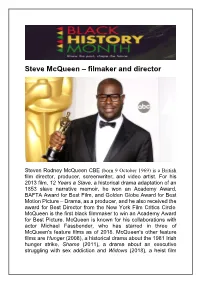

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

BFI Poll Reveals UK's Favourite Black Star Performance

BFI POLL REVEALS UK’S FAVOURITE BLACK STAR PERFORMANCE: SIDNEY POITIER AS “MISTER TIBBS” In the Heat of the Night Angela Bassett’s courageous portrayal of Tina Turner in What’s Love Got to Do with It voted as top performance by over 100 industry experts London: (embargoed until 16:30 BST) Thursday 20 October, 2016 – To mark this week’s official launch of its BLACK STAR season, the BFI announced today that Sidney Poitier’s critically-acclaimed and seminal performance as Detective Virgil Tibbs in In the Heat of the Night (dir. Norman Jewison, 1967) has been voted the public’s Favourite Black Star Performance in a poll which included 100 performances spanning over 80 years in film and TV. Running alongside the public poll, a separate poll of over 100 industry experts voted for Angela Bassett’s Oscar®- nominated performance as Tina Turner in What’s Love Got to Do with It (dir. Brian Gibson, 1993). UK Public Poll Pam Grier followed in second place with her terrific turn as the titular character in Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown – an homage to the 1970’s era of Blaxploitation films in America; Michael K. Williams was number three with his unforgettable portrayal of the legendary Omar Little, the openly gay, notorious stick-up man with a strict moral code feared by drug dealers across the city of Baltimore, in the socially and politically charged hit television series The Wire. British actor Chiwetel Ejiofor followed in fourth with his visceral portrayal of Solomon Northup, his break-out performance in Steve McQueen’s ground-breaking, Oscar®-winning true story, 12 Years A Slave; and Morgan Freeman rounded out the top five with his acclaimed, quiet and layered performance in Frank Darabont’s Oscar®-nominated cult classic, The Shawshank Redemption. -

Widescreen Weekend 2008 Brochure (PDF)

A5 Booklet_08:Layout 1 28/1/08 15:56 Page 41 THIS IS CINERAMA Friday 7 March Dirs. Merian C. Cooper, Michael Todd, Fred Rickey USA 1952 120 mins (U) The first 3-strip film made. This is the original Cinerama feature The Widescreen Weekend continues to welcome all which launched the widescreen those fans of large format and widescreen films – era, and is about as fun a piece of CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and IMAX – Americana as you are ever likely and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of to see. More than a technological curio, it's a document of its era. the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the nostalgic best of cinema. HAMLET (70mm) Sunday 9 March Widescreen Passes £70 / £45 Dir. Kenneth Branagh GB/USA 1996 242 mins (PG) Available from the box office 0870 70 10 200 Kenneth Branagh, Julie Christie, Derek Jacobi, Kate Winslet, Judi Patrons should note that tickets for 2001: A Space Odyssey are priced Dench, Charlton Heston at £10 or £7.50 concessions Anyone who has seen this Hamlet in 70mm knows there is no better-looking version in colour. The greatest of Kenneth Branagh’s many achievements so 61 far, he boldly presents the full text of Hamlet with an amazing cast of actors. STAR! (70mm) Saturday 8 March Dir. Robert Wise USA 1968 174 mins (U) Julie Andrews, Daniel Massey, Richard Crenna, Jenny Agutter Robert Wise followed his box office hits West Side Story and The Sound of Music with Star! Julie 62 63 Andrews returned to the screen as Gertrude Lawrence and the film charts her rise from the music hall to Broadway stardom. -

The Forgotten Revolution of Female Punk Musicians in the 1970S

Peace Review 16:4, December (2004), 439-444 The Forgotten Revolution of Female Punk Musicians in the 1970s Helen Reddington Perhaps it was naive of us to expect a revolution from our subculture, but it's rare for a young person to possess knowledge before the fact. The thing about youth subcultures is that regardless how many of their elders claim that the young person's subculture is "just like the hippies" or "just like the mods," to the committed subculturee nothing before could possibly have had the same inten- sity, importance, or all-absorbing life commitment as the subculture they belong to. Punk in the late 1970s captured the essence of unemployed, bored youth; the older generation had no comprehension of our lack of job prospects and lack of hope. We were a restless generation, and the young women among us had been led to believe that a wonderful Land of Equality lay before us (the 1975 Equal Opportunities Act had raised our expectations), only to find that if we did enter the workplace, it was often to a deep-seated resentment that we were taking men's jobs and depriving them of their birthright as the family breadwinner. Few young people were unaware of the angry sound of the Sex Pistols at this time—by 1977, a rash of punk bands was spreading across the U.K., whose aspirations covered every shade of the spectrum, from commercial success to political activism. The sheer volume of bands caused a skills shortage, which led to the cooption of young women as instrumentalists into punk rock bands, even in the absence of playing experience. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

POPULAR MUSIC from the 1970S

POPULAR MUSIC FROM THE 1970s Week of May 18 1. Watch the video “Elders React to Top Ten Songs of 1970s” Video - Elders React to 1970s 2. MUSIC OF THE 1970s: A few trends The 1970s saw many styles of popular music and countless numbers of recording artists. This week you will experience a mere taste of three types of music from this diverse decade. ● HARD ROCK - These artists turned up the volume. ● COUNTRY ROCK/SOUTHERN ROCK - Country music sensibilities + rock instruments ● DISCO - It was all about providing music so people could “boogie” (1970s slang for “dance.”) Your task: Choose one song in each of the three categories below (for a total of three songs.) Find and listen to all three. Come back to them a day or two later and listen to them again so you become especially familiar with them. (Note: If you don’t like one of the songs you first choose, choose a different one) HARD ROCK (choose one) Led Zeppelin - Stairway To Heaven Queen - Bohemian Rhapsody Aerosmith - Walk This Way COUNTRY ROCK / SOUTHERN ROCK (choose one) Linda Ronstadt - You’re No Good The Eagles - Hotel California Lynyrd Skynyrd - Sweet Home Alabama DISCO (choose one) The Bee Gees - Stayin’ Alive Donna Summer - Last Dance KC and the Sunshine Band - That’s the Way I Like It Earth, Wind and Fire - Boogie Wonderland You will not submit anything this week; just enjoy the music! Week of May 25 Music of the 1970s: Become an Expert (Take two weeks to complete this assignment) Select one musical act from the 1970s. -

Robert De Niro Sr

June 27, 2014 12:44 pm Portrait of an artist: Robert De Niro Sr By Liz Jobey Robert De Niro does not star in his latest film but he did make and narrate it – a documentary about his artist father, whose work remains little known despite great early success Robert De Niro and his father, New York, c 1983 There are two entries for Robert De Niro in the online collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. One is for Taxi Driver, the film directed by Martin Scorsese, for which De Niro was nominated for an Oscar as best actor in 1976; the other is for Raging Bull, also directed by Scorsese and for which De Niro won the award for best actor in 1980. At the Metropolitan Museum, however, the name Robert De Niro tells a different story. Four entries are listed – two drawings in crayon from 1976, a charcoal drawing from 1941 and a self-portrait in oil dated 1951. These are works by Robert De Niro Sr, the actor’s father, a relatively unknown American painter, who died in 1993. He had early success in the 1940s and 1950s, part of a group that included Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and Franz Kline, the core of American Abstract Expressionism, and his portrait came to the museum in 2006, part of the bequest of Muriel Kallis Steinberg Newman, a leading collector. The image is not on view but is accompanied by the following caption: The critic Clement Greenberg pronounced De Niro “an important young abstract painter” upon seeing his 1946 show at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery, Art of This Century.