A Case Study of User-Group Representatives in Fisheries Management in Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annex 13 Master Plan on Sswrd in Mymensingh District

ANNEX 13 MASTER PLAN ON SSWRD IN MYMENSINGH DISTRICT JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MINISTRY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT, RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND COOPERATIVES (MLGRD&C) LOCAL GOVERNMENT ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT (LGED) MASTER PLAN STUDY ON SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION THROUGH EFFECTIVE USE OF SURFACE WATER IN GREATER MYMENSINGH MASTER PLAN ON SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN MYMENSINGH DISTRICT NOVEMBER 2005 PACIFIC CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL (PCI), JAPAN JICA MASTER PLAN STUDY ON SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION THROUGH EFFECTIVE USE OF SURFACE WATER IN GREATER MYMENSINGH MASTER PLAN ON SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN MYMENSINGH DISTRICT Map of Mymensingh District Chapter 1 Outline of the Master Plan Study 1.1 Background ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 1 1.2 Objectives and Scope of the Study ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 1 1.3 The Study Area ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 2 1.4 Counterparts of the Study ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 2 1.5 Survey and Workshops conducted in the Study ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 3 Chapter 2 Mymensingh District 2.1 General Conditions ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 4 2.2 Natural Conditions ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 4 2.3 Socio-economic Conditions ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 5 2.4 Agriculture in the District ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 5 2.5 Fisheries -

Rivers of Peace: Restructuring India Bangladesh Relations

C-306 Montana, Lokhandwala Complex, Andheri West Mumbai 400053, India E-mail: [email protected] Project Leaders: Sundeep Waslekar, Ilmas Futehally Project Coordinator: Anumita Raj Research Team: Sahiba Trivedi, Aneesha Kumar, Diana Philip, Esha Singh Creative Head: Preeti Rathi Motwani All rights are reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission from the publisher. Copyright © Strategic Foresight Group 2013 ISBN 978-81-88262-19-9 Design and production by MadderRed Printed at Mail Order Solutions India Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India PREFACE At the superficial level, relations between India and Bangladesh seem to be sailing through troubled waters. The failure to sign the Teesta River Agreement is apparently the most visible example of the failure of reason in the relations between the two countries. What is apparent is often not real. Behind the cacophony of critics, the Governments of the two countries have been working diligently to establish sound foundation for constructive relationship between the two countries. There is a positive momentum. There are also difficulties, but they are surmountable. The reason why the Teesta River Agreement has not been signed is that seasonal variations reduce the flow of the river to less than 1 BCM per month during the lean season. This creates difficulties for the mainly agrarian and poor population of the northern districts of West Bengal province in India and the north-western districts of Bangladesh. There is temptation to argue for maximum allocation of the water flow to secure access to water in the lean season. -

Assessment of Soil Loss of the Dhalai River Basin, Tripura, India Using USLE

International Journal of Geosciences, 2013, 4, 11-23 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijg.2013.41002 Published Online January 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ijg) Assessment of Soil Loss of the Dhalai River Basin, Tripura, India Using USLE Kapil Ghosh, Sunil Kumar De*, Shreya Bandyopadhyay, Sushmita Saha Department of Geography and Disaster Management, Tripura University, Suryamaninagar, India Email: *[email protected] Received September 27, 2012; revised November 12, 2012; accepted December 11, 2012 ABSTRACT Soil erosion is one of the most important environmental problems, and it remains as a major threat to the land use of hilly regions of Tripura. The present study aims at estimating potential and actual soil loss (t·h−1·y−1) as well as to in- dentify the major erosion prone sub-watersheds in the study area. Average annual soil loss has been estimated by multi- plying five parameters, i.e.: R (the rainfall erosivity factor), K (the soil erodibility factor), LS (the topographic factor), C (the crop management factor) and P (the conservation support practice). Such estimation is based on the principles de- fined in the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE) with some modifications. This intensity of soil erosion has been di- vided into different priority classes. The whole study area has been subdivided into 23 sub watersheds in order to iden- tify the priority areas in terms of the intensity of soil erosion. Each sub-watershed has further been studied intensively in terms of rainfall, soil type, slope, land use/land cover and soil erosion to determine the dominant factor leading to higher erosion. -

A Case Study on Deepor Beel: the Ramsar Site and the Most

A case study on Deepor Beel: The Ramsar site and the most prominent flood plain wetland of Brahmaputra The genesis Deepor Beel Wildlife Sanctuary and the Ramsar site of international importance recognized under the Ramsar Convention, 1971, located about 18 km southwest of Guwahati city between 90036∕ 39∕∕ E and 91041∕∕25∕∕ E longitude and 26005∕26∕∕ N and 2609∕26∕∕ N latitude and 55 m above the mean sea level is considered as one of the largest and prominent flood-plain lakes in the Brahmaputra valley in Ramcharani Mouza of Guwahati sub-division under Kamrup (Metropolitan) district. Deepor Beel included in the Directory of Asian Wetlands as a wetland type 14 is an open beel connected with a set of inflow and out flow channels. The main inlets of the beel are the Mara Bharalu and the Basishtha-Bahini rivers which carry the sewage as well as rain water from Guwahati city. The only outlet of the beel is Khanajan located towards the north- east having connection with the main river Brahmaputra. Another outlet, Kalmoni has now no existence due to the rampant construction over the channel. Conservation History of Deepor Beel 1989: Preliminary notification of Deepor Beel Wildlife Sanctuary vide FRW 1∕89∕25, 12 January (Area - 4.1sq. km.) 1997: Formation of Deepor beel Management Authority by Government of Assam 2002: Declaration of Ramsar site (Area - 40 sq. km.) 2004: Declaration of Important Bird Area (IBA) by Birdlife International 2009: Final notification of Deepor Beel Wildlife Sanctuary vide FRM 140∕2005∕260, 21 February (Area - 4.1sq. -

A Checklist of Fishes and Fisheries of the Padda (Padma) River Near Rajshahi City

Available online at www.ijpab.com Farjana Habib et al Int. J. Pure App. Biosci. 4 (2): 53-57 (2016) ISSN: 2320 – 7051 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18782/2320-7051.2248 ISSN: 2320 – 7051 Int. J. Pure App. Biosci. 4 (2): 53-57 (2016) Research Article A checklist of Fishes and Fisheries of the Padda (Padma) River near Rajshahi City Farjana Habib 1*, Shahrima Tasnin 1 and N.I.M. Abdus Salam Bhuiyan 2 1Research Scholar, 2Professor Department of Zoology, University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh *Corresponding Author E-mail: [email protected] Received: 22.03.2016 | Revised: 30.03.2016 | Accepted: 5.04.2016 ABSTRACT The present study was carried out to explore the existing fish fauna of the Padda (Padma) River near Rajshahi City Corporation area for a period of seven months (February to August). This study includes a checklist of the species composition found to inhabit the waters of this region, which included 82 species of fishes under 11 orders and two classes. The list also includes two species of prawns. A total of twenty nine fish species of the study area are recorded as threatened according to IUCN red list. This finding will help to evaluate the present status of fishes in Padda River and their seasonal abundance. Key words : Exotic, Endangered, Rajshahi City, Padda (Padma) River INTRODUCTION Padda is one of the main rivers of Bangladesh. It Kilometers (1,400 mi) from the source, the is the main distributary of the Ganges, flowing Padma is joined by the Jamuna generally southeast for 120 kilometers (75 mi) to (Lower Brahmaputra) and the resulting its confluence with the Meghna River near combination flows with the name Padma further the Bay of Bengal 1. -

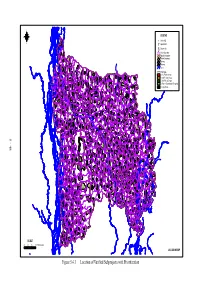

Figure 5.4.1 Location of Verified Subprojects with Prioritization CHAPTER 6 MASTER PLAN on SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT

N LEGEND W E Y Union HQ 339 15 01 0 S Y 339 15 02 0 Y# Upazila HQ Y 339 15 03 0 %[ District HQ Y Union Boundary 339 15 05 0 33915041 Upazila Boundary 339 07 05 0 District Boundary Y 33907010Y Y Railway 339 07 06 0 38990010Y Highway 389 37 01 0 Y339 15 06 0 Y River 339 07 04 0 339 07 02Y 0 Y Y Y Y Y Y Y# 389 37 02 0 Y# 38970020 389 70 03 0 SP Priority Type 38970010 339 15 07 2Y 33907030 Y Y36124010 389 37 04 1 Y Y Y A: 1st Priority Group Y Y 372 18 01 0 361 16 03 0 Y# 36116020 Y Y Y 389 70 04 0 Y 37218021 Y 37240020 Y Y Y Y Y 37240040 B: 2nd Priority Group 339 07 07 0 361 24 02 0 37218022 38990030 36124110 33915080 Y# 372 40 03 0 Y Y 361 24 10 0 Y Y Y 38990022 389 70 08 0 Y C: 3rd Priority Group Y Y Y Y 361 16 01 0 Y Y# 33929010 33929090 Y 38970051 389 70 06 0 Y Y# Y Y 339 29 08 0 Y 37218023 389 37 03 2 D: Further Examination Required 389 90 05 1 38937050 Y 361 16 05 0 Y 389 70 07 0 Y 389 90 04Y 0 361 16 04 0 37218030 339 29 03 0 Y Y Y Y Y 372 40 05 0 372 40 07 0 Y# Y 372 40 08 0 Y 33929100 339 29 13 0 L: Large Scale Y Y 36124120 Y Y Y# 37240060 Y Y 37218050 Y# Y 389 70 09 0 36124030 Y# 389 70 11 0 Y Y Y Y 372Y 18 06 0 38970120 Y 36116060 339 29 04 0 Y Y 36124050 Y SHERPUR 361 24 09 0 339 29 07 0 38970101 Y 389 88 02 0 372 18 07 0 339 29 12 0 Y 36124040 36124060 37240090 Y 372 40 10 0 389 88 03 0 Y Y Y Y 361 24 07 0 Y Y Y 37240110 389 88 01 0 Y Y 38988060 Y Y 36124080 339 29 06 0 339 61 04 4 %[ Y Y 37274010 Y Y 372 83 03 0 389 88 07 0 Y 372 40 12 0 389 88 08 0 Y 37283012 Y# 38967010 372 83 06 0 36181010 Y 339 61 01 0 Y 36181060 Y Y Y 372 -

Bangladesh Delta Plan (BDP) 2100 (Bangladesh in the 21St Century)

Bangladesh Delta Plan (BDP) 2100 (Bangladesh in the 21st Century) Mohammad Asaduzzaman Sarker Senior Assistant Chief General Economics Division Bangladesh Planning Commission Bangladesh Delta Features . Built on the confluence of 3 mighty Rivers- the Ganges, the Brahmaputra and the Meghna; . Largest dynamic delta of the world; . Around 700 Rivers: 57 Trans-boundary (54 with India and 3 with Myanmar); . 93% catchment area lies outside Bangladesh with annual sediment load of 1.0 to 1.4 billion tonnes; . Abundance of water in wet season but scarcity of water in dry season. January 21, 2019 GED, Bangladesh Planning Commission 2 Bangladesh Delta Challenges According to IPCC-AR 5 and other studies . Rising Temperatures (1.4-1.90C increase by 2050, if extreme then 20C plus) . Rainfall Variability (overall increase by 2030, but may decrease in Eastern and southern areas) . Increased Flooding (about 70% area is within 1m from Sea Level) . Droughts (mainly Agricultural Drought) . River Erosion (50,000 households on avg. become homeless each year) . Sea Level Rise (SLR) and consequent Salinity Intrusion (by 2050 SLR may be up to 0.2-1.0 m; salinity increase by 1ppt in 17.5% & by 5ppt in 24% area) . Cyclones and Storm Surges (Frequency and category will increase along with higher storm surges) . Water Logging . Sedimentation . Trans-boundary Challenges 3 GED, Bangladesh Planning Commission Bangladesh Delta Opportunities Highly fertile land The Sundarbans . Agricultural land: 65% . The largest natural mangrove forest . Forest lands: 17% . Unique ecosystem covers an area of 577,000 ha of . Urban areas: 8% which 175,400 ha is under water . Water and wetlands: 10%. -

Information Systems for the Co-Management of Artisanal Fisheries

Information Systems for the Co-Management of Artisanal Fisheries Field Study 1 - Bangladesh UK Department for International Development Fisheries Management Science Programme Project R7042 MRAG Ltd 47 Prince’s Gate South Kensington London SW7 2QA April 1999 Information Systems for the Co-Management of Artisanal Fisheries Field Study 1 - Bangladesh Funding: UK Department for International Development (DFID) Renewable Natural Resources Research Strategy (RNRRS) Fisheries Management Science Programme (FMSP) Project R7042 Collaborators: CARE, Bangladesh, 65 Road No. 7/A, Dhanmondi, Dhaka 1209, Bangladesh Centre for Natural Resource Studies (CNRS), 3/14 Iqbal Road, Ground Floor, Block A Mohammadpur, Dhaka - 1207, Bangladesh Authors: Dr A. S. Halls Mr R. Lewins (Chapter 7) Contents Contents .................................................................1 1. Executive Summary ..................................................5 2. Introduction .......................................................11 2.1 The Objectives of the Project.....................................11 2.2 Objectives of the Field Based Study ...............................11 2.3 Field Study Approach ..........................................11 2.4 Field Work Team..............................................12 2.5 Structure of the Report..........................................13 3. Inland Fisheries and Aquaculture .....................................15 3.1 Background ..................................................15 3.2 Inland Fisheries and the Environment ..............................16 -

Factor Analysis of Water-Related Disasters in Bangladesh

ISSN 0386-5878 Technical Note of PWRI No.4068 Factor Analysis of Water-related Disasters in Bangladesh June 2007 The International Centre for Water Hazard and Risk Management PUBLIC WORKS RESEARCH INSTITUTE 1-6, Minamihara Tukuba-Shi, Ibaraki-Ken, 305-8516 Copyright ○C (2007) by P.W.R.I. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language without the written permission of the Chief Executive of P.W.R.I. この報告書は、独立行政法人土木研究所理事長の承認を得て刊行したものであ る。したがって、本報告書の全部又は一部の転載、複製は、独立行政法人土木研 究所理事長の文書による承認を得ずしてこれを行ってはならない。 Technical Note of PWRI No.4068 Factor Analysis of Water-related Disasters in Bangladesh by Junichi YOSHITANI Norimichi TAKEMOTO Tarek MERABTENE The International Centre for Water Hazard and Risk Managemant Synopsis: Vulnerability to disaster differs considerably depending on natural exposure to hazards and social conditions of countries affected. Therefore, it is important to take practical disaster mitigating measures which meet the local vulnerability conditions of the region. Designating Bangladesh as a research zone, this research aims to propose measures for strengthening the disaster mitigating system tailored to the region starting from identifying the characteristics of the disaster risk threatening the country. To this end, we identified the country’s natural and social characteristics first, and then analyzed the risk challenges and their background as the cause to create and expand the water-related disasters. Furthermore, we also analyzed the system -

Beel Fishery and Livelihood of the Local Community in Rajdhala, Netrakona, Bangladesh

Beel fishery and livelihood of the local community in Rajdhala, Netrakona, Bangladesh Item Type article Authors Rahman, M.A.; Haque, M.M. Download date 26/09/2021 05:30:05 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/33369 Bangladesh J, Fish. Res., 12(1 ), 2008: 95-108 Beel fishery and livelihood of the local community in Rajdhala, Netrakona, Bangladesh M.A. Rahman1'* and M.M. Haque Department of Fisheries Management, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh 2202, Bangladesh 1Ptresent address: Bangladesh Fisheries Research Institute, Riverine Station, Chandpur 3602 *Corresponding author Abstract Baseline survey and Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) during January 2003 to December 2004 on the fishing community revealed that unregulated fishing, use of destructive fishing gears, poaching of fishes, difficulties encountered in enforcing fisheries regulation and the helplessness of fishers to find alternative sources of income during banned fishing period (June to October) were the major management problems. CBFM (Community Based Fisheries Management) system as an alternative management strategy has been introduced to ensure active participation of the target group-the poor fishers living around the beet who were previously deprived to get access to the beet. Establishing a leasing system for controlled access, ensuring greater user-group participation through equitable distribution of all resource benefits among members, attempting to enforce penalties for illegal fishing linked with surprise checks to enforce management regulations are some of the recent steps taken by the BMC (Beet Management Committee). Chapila fish intake by the community was 31.25 g/head/day before stocking the beet by carp fingerlings. After stocking, they consumed chapila as fish protein from 8.33 g to 20.8 g/head/day during the fishing season (November to May) indicating that due to introduction of carp fingerlings, chapila production has been decreased in 2003-2004. -

Decline in Fish Species Diversity Due to Climatic and Anthropogenic Factors

Heliyon 7 (2021) e05861 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Heliyon journal homepage: www.cell.com/heliyon Research article Decline in fish species diversity due to climatic and anthropogenic factors in Hakaluki Haor, an ecologically critical wetland in northeast Bangladesh Md. Saifullah Bin Aziz a, Neaz A. Hasan b, Md. Mostafizur Rahman Mondol a, Md. Mehedi Alam b, Mohammad Mahfujul Haque b,* a Department of Fisheries, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi, Bangladesh b Department of Aquaculture, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh, Bangladesh ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This study evaluates changes in fish species diversity over time in Hakaluki Haor, an ecologically critical wetland Haor in Bangladesh, and the factors affecting this diversity. Fish species diversity data were collected from fishers using Fish species diversity participatory rural appraisal tools and the change in the fish species diversity was determined using Shannon- Fishers Wiener, Margalef's Richness and Pielou's Evenness indices. Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted Principal component analysis with a dataset of 150 fishers survey to characterize the major factors responsible for the reduction of fish species Climate change fi Anthropogenic activity diversity. Out of 63 sh species, 83% of them were under the available category in 2008 which decreased to 51% in 2018. Fish species diversity indices for all 12 taxonomic orders in 2008 declined remarkably in 2018. The first PCA (climatic change) responsible for the reduced fish species diversity explained 24.05% of the variance and consisted of erratic rainfall (positive correlation coefficient 0.680), heavy rainfall (À0.544), temperature fluctu- ation (0.561), and beel siltation (0.503). The second PCA was anthropogenic activity, including the use of harmful fishing gear (0.702), application of urea to harvest fish (0.673), drying beels annually (0.531), and overfishing (0.513). -

ADMINISTRATION and POLITICS in TRIPURA Directorate of Distance Education TRIPURA UNIVERSITY

ADMINISTRATION AND POLITICS IN TRIPURA MA [Political Science] Third Semester POLS 905 E EDCN 803C [ENGLISH EDITION] Directorate of Distance Education TRIPURA UNIVERSITY Reviewer Dr Biswaranjan Mohanty Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, SGTB Khalsa College, University of Delhi Authors: Neeru Sood, Units (1.4.3, 1.5, 1.10, 2.3-2.5, 2.9, 3.3-3.5, 3.9, 4.2, 4.4-4.5, 4.9) © Reserved, 2017 Pradeep Kumar Deepak, Units (1.2-1.4.2, 4.3) © Pradeep Kumar Deepak, 2017 Ruma Bhattacharya, Units (1.6, 2.2, 3.2) © Ruma Bhattacharya, 2017 Vikas Publishing House, Units (1.0-1.1, 1.7-1.9, 1.11, 2.0-2.1, 2.6-2.8, 2.10, 3.0-3.1, 3.6-3.8, 3.10, 4.0-4.1, 4.6-4.8, 4.10) © Reserved, 2017 Books are developed, printed and published on behalf of Directorate of Distance Education, Tripura University by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material, protected by this copyright notice may not be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form of by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the DDE, Tripura University & Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge.