Post-War School Building with Special Reference to the Problems Faced by the Hampshire Local Education Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warblington Its Castle and Its Church Havant History Booklet No.62

Warblington Its Castle and Its Church Warblington church circa 1920 Historical Notes of a Parish in South Hampshire by W. B. Norris and C. O. Minchin Havant History Booklet No. 62 Havant Emsworth Museum £4 Museum The Yew tree in the churchyard is believed to be over 1,500-years-old Margaret Pole, The Oak north porch circa 1920 Countess of Salisbury 2 This history was originally published in 1920. It has been scanned and reprinted as part of the series of booklets on the history of the Borough of Havant. Ralph Cousins January 2016 Read also Havant Borough History Booklet No. 6: A Short History of Emsworth and Warblington by A. J. C. Reger Read, comment, and order all booklets at hhbkt.com 3 Preface Much of the material embodied in this little history of Warblington has been taken from a book called The Hundred of Bosmere (comprising the Parishes of Havant, Warblington, and Hayling Island). Original copies are now very scarce [it has been re-printed and is also available to read on the web]. It was published in 1817 by the Havant Press, and, though anonymous, is well-known to have been written by Mr Walter Butler, Solicitor, of Havant, who combined a profound knowledge of the records of this part of the County of Hampshire with much patience in research. We have to express our thanks to the proprietors of the Hampshire Telegraph and the Portsmouth Times for permission to use several extracts from articles on the County which appeared in those papers some years since; and to Mrs Jewell, of Emsworth, in this Parish, for information which her great age and most retentive memory have enabled her, most kindly, to place at our service. -

Appeal by Bargate Homes, Land at Lower Road, Bedhampton Pins Reference: App/X1735/W/20/3259067 Closing Submissions on Behalf Of

APPEAL BY BARGATE HOMES, LAND AT LOWER ROAD, BEDHAMPTON PINS REFERENCE: APP/X1735/W/20/3259067 CLOSING SUBMISSIONS ON BEHALF OF HAVANT BOROUGH COUNCIL Structure (1) The development plan (Inspector’s issue 3) (2) Harm to the Old Bedhampton Conservation Area (Inspector’s issue 1) (3) Public benefits (Inspector’s issue 1) (4) Other material considerations (5) The planning balance (Inspector’s Issue 3) (6) Conclusion The development plan: main policies and weight 1 The development plan comprises the Havant Borough Core Strategy and the Havant Borough Local Plan (Allocations) development plan document (the “Allocations Plan”). The plans were adopted in March 2011 and July 2014 respectively. The plan period is 2006 to 2026. The spatial strategy 2 Core Strategy policy CS9 makes provision for the delivery of some 6,300 homes. They are to be developed in accordance with the spatial strategy specified by policy CS17. It concentrates new housing in the Borough’s five main urban areas. It also prioritises the re-use of previously developed land and buildings within those areas. Development in the countryside is to be controlled “in accordance with national policy”. That must mean in accordance with paragraphs 77 to 79 of the National Planning Policy Framework. 3 The boundaries of the urban areas are defined by Allocations Plan Policy AL2 and the Policies Map. The appeal site is located outside the urban boundary of Havant and Bedhampton. Officers concluded that the result is the proposal conflicts with the development plan.[1] Mr Wood agrees. Each is plainly correct. 4 The Core Strategy pre-dates the publication of the National Planning Policy Framework. -

Parish Churches of the Test Valley

to know. to has everything you need you everything has The Test Valley Visitor Guide Visitor Valley Test The 01264 324320 01264 Office Tourist Andover residents alike. residents Tourist Office 01794 512987 512987 01794 Office Tourist Romsey of the Borough’s greatest assets for visitors and and visitors for assets greatest Borough’s the of villages and surrounding countryside, these are one one are these countryside, surrounding and villages ensure visitors are made welcome to any of them. of any to welcome made are visitors ensure of churches, and other historic buildings. Together with the attractive attractive the with Together buildings. historic other and churches, of date list of ALL churches and can offer contact telephone numbers, to to numbers, telephone contact offer can and churches ALL of list date with Bryan Beggs, to share the uniqueness of our beautiful collection collection beautiful our of uniqueness the share to Beggs, Bryan with be locked. The Tourist Offices in Romsey and Andover hold an up to to up an hold Andover and Romsey in Offices Tourist The locked. be This leaflet has been put together by Test Valley Borough Council Council Borough Valley Test by together put been has leaflet This church description. Where an is shown, this indicates the church may may church the indicates this shown, is an Where description. church L wide range of information to help you enjoy your stay in Test Valley. Valley. Test in stay your enjoy you help to information of range wide every day. Where restrictions apply, an is indicated at the end of the the of end the at indicated is an apply, restrictions Where day. -

2019 Pdppr - List of Polling Stations and Streets by Polling District (Proposed) 25 10 2019 Tuesday, 29 October 2019

REVIEW OF POLLING DISTRICT AND POLLING PLACES (Parliamentary Elections) Regulations 2006 ALVERSTOKE WARD (GA) GA1 GOMER COUNTY INFANT SCHOOL, PYRFORD CLOSE, GOSPORT. Broadsands Drive (Gomer, Cadnam, Marchwood, Seaview & Woolston Courts); Broadsands Walk; Browndown Road; Churcher Close; Churcher Walk; Gale Moor Avenue (Milford, Moat, Whitecliffe & Wickham Courts); Gomer Lane (54-68 evens, School House, Cornerways, The Last House, The Cottage Stanley Park) Martello Close; Moat Drive; Moat Walk; Nasmith Close; Portland Drive; Sandcroft Close; Sandford Avenue; Sandown Close; Stokes Bay Road (Stokes Bay Mobile Home Park); Tower Close (Ashurst, Fairoak & Shirrell Courts). ELECTORATE 1,160 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLLING DISTRICT GA1: (1) that no changes be made to polling district GA1 (2) Gomer Infant School, Pyrford Close, be designated the polling place for the polling district GA2 ALVERSTOKE CE AIDED JUNIOR SCHOOL, THE AVENUE, GOSPORT. Anglesey Road (2-54 evens); Avenue Court; Beatty Drive; Beech Grove; Brodrick Avenue; Bury Hall Lane (2-32 evens, 1&1a); Bury Road (63-101a odds); Green Lane (Dolphin House); Halsey Close; Jellicoe Avenue; Kingsmill Close; Little Green; Little Green Orchard; Lodge Gardens; Mound Close; Northcott Close (Wallis Bungalows, Glen House, Northcott House); Sherwin Walk; Tebourba Drive; The Avenue; The Paddock; Westland Gardens. ELECTORATE 1,236 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLLING DISTRICT GA2: (1) that no changes be made to polling district GA2 (2) Alverstoke CE (Aided) Junior School, The Avenue, be designated the polling place for the polling district GA3 ALVERSTOKE COUNTY INFANT SCHOOL, ASHBURTON ROAD, GOSPORT. Alvercliffe Drive; Anglesey Road (64-70 evens, Anglesey Lodge, Orchard House, Landon Court); Ashburton Road (Rodney House); Bankside; Church Road (Charlotte Mews, Alverstoke Court); Coastguard Close; Coward Road; Elgar Close; Green Road; Jellicoe Avenue (95-119 odds & 86-130 evens); Kennedy Crescent; Little Lane; Paget Road; Palmerston Way; Solent Way; South Close; Stokes Bay Road (1 odds), Sword Close; The Spur; Village Road; Western Way. -

654 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

654 bus time schedule & line map 654 Hambledon - Havant Campus View In Website Mode The 654 bus line (Hambledon - Havant Campus) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Denmead: 3:45 PM (2) Hambledon: 3:34 PM - 4:25 PM (3) Havant: 8:00 AM - 8:14 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 654 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 654 bus arriving. Direction: Denmead 654 bus Time Schedule 18 stops Denmead Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 3:45 PM Oaklands School, Purbrook Tuesday 3:45 PM Oaklands School, Stakes Wednesday 3:45 PM Stakes Lodge, Stakes Thursday 3:45 PM Elmwood Avenue, Waterlooville Friday 3:45 PM Precinct, Waterlooville Saturday Not Operational Saint Georges Walk, Portsmouth Hulbert Road Roundabout, Waterlooville Jubilee Road, Waterlooville 654 bus Info Direction: Denmead Highƒeld Avenue, Waterlooville Stops: 18 Trip Duration: 25 min 193 London Road, Portsmouth Line Summary: Oaklands School, Purbrook, Queens Road, Cowplain Oaklands School, Stakes, Stakes Lodge, Stakes, Elmwood Avenue, Waterlooville, Precinct, Waterlooville, Hulbert Road Roundabout, Community School, Cowplain Waterlooville, Jubilee Road, Waterlooville, Highƒeld Hart Plain Avenue, Portsmouth Avenue, Waterlooville, Queens Road, Cowplain, Community School, Cowplain, Silverdale Drive, Silverdale Drive, Waterlooville Waterlooville, Clinton Road, Waterlooville, The Falcon, Sunnymead Drive, Portsmouth Waterlooville, Sunnymead Drive, Waterlooville, Soake Clinton Road, Waterlooville Road, Soake, Mill -

The Test Valley (Electoral Changes) Order 2018

Draft Order laid before Parliament under section 59(9) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009; draft to lie for forty days pursuant to section 6(1) of the Statutory Instruments Act 1946, during which period either House of Parliament may resolve that the Order be not made. DRAFT STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2018 No. LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Test Valley (Electoral Changes) Order 2018 Made - - - - *** Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) and (3) Under section 58(4) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009( a) (“the Act”), the Local Government Boundary Commission for England( b) (“the Commission”) published a report dated October 2017 stating its recommendations for changes to the electoral arrangements for the borough of Test Valley. The Commission has decided to give effect to those recommendations. A draft of the instrument has been laid before each House of Parliament, a period of forty days has expired since the day on which it was laid and neither House has resolved that the instrument be not made. The Commission makes the following Order in exercise of the power conferred by section 59(1) of the Act. Citation and commencement 1. —(1) This Order may be cited as the Test Valley (Electoral Changes) Order 2018. (2) This article and article 2 come into force on the day after the day on which this Order is made. (3) The remainder of this Order comes into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary, or relating, to the election of councillors, on the day after the day on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in England and Wales( c) in 2019. -

Week Ending 17Th February 2017

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 7 Week Ending: 17th February 2017 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column Head of Planning and Building Beech Hurst Weyhill Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 17/00365/TREEN Reduce lowest branch - Church Meadows, Opposite St Mrs Caroline Land Miss Rachel Cooke YES 13.02.2017 Horse Chestnut T1. Reduce Marys Church, Church Lane 07.03.2017 ABBOTTS ANN and thin canopy, reduce Footpath, Abbotts Ann Andover lowest branch - Horse Hampshire Chestnut T2. Reduce canopy - Horse Chestnut T3. 17/00439/FULLN Removal of existing shed 11 Wellington Road, Andover, Mrs Kerry Brown Mrs Donna Dodd 17.02.2017 and erection of a single Hampshire, SP10 3JW 15.03.2017 ANDOVER TOWN storey outbuilding for use as (HARROWAY) storage unit, workshop and gym 17/00315/FULLN Installation -

2014 Air Quality Progress Report for Fareham Borough Council

2014 Air Quality Progress Report for Fareham Borough Council In fulfillment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management October 2014 LAQM Progress Report 2014 1 Fareham Borough Council Local Authority Heather Cusack Officer Department Regulatory Services Civic Offices Civic Way Address Fareham Hampshire PO16 7AZ Telephone 01329 236100 e-mail [email protected] Report Reference LAQM PROGRESS REPORT 2014 number Date October 2014 Alex Moon Prepared by Technical Officer Date October 2014 Ian Rickman Approved by Shared Head of Environmental Health Partnership Date October 2014 Signature LAQM Progress Report 2014 2 Fareham Borough Council Executive Summary Fareham Borough Council has undertaken this 2014 progress report in fulfilment of the Local Air Quality Management (LAQM) process as set out in Part IV of the Environment Act (1995), the Air Quality Strategy (AQS) for England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland 2007 and the relevant Policy and Technical Guidance documents. Two Air Quality Management Areas (AQMAs) are still currently in place at Gosport Road and Portland Street for nitrogen dioxide (NO2). Following the conclusions of this report it is recommended that the present AQMA declarations should remain. The monitoring data for 2013 has indicated that the annual mean NO2 objective was achieved at all monitoring locations except for two sites within the existing AQMAs that is, G7 and PS3 and one site outside the existing AQMAs, G10. A detailed assessment was conducted at G10 in 2010 which showed no exceedances at the façade of the properties and the AQMAs were not adjusted. As the exceedance is marginal (40.50µg/m3), a continuation of monitoring will take place in order to fully assess whether a detailed assessment is required in the future. -

View Document Or Right Click for Other Options

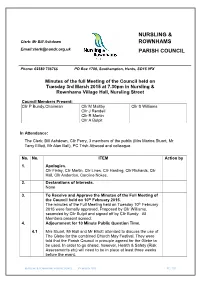

NURSLING & Clerk: Mr Bill Ashdown ROWNHAMS Email:[email protected] PARISH COUNCIL Phone: 02380 736766 PO Box 1780, Southampton, Hants, SO15 9FX Minutes of the full Meeting of the Council held on Tuesday 3rd March 2015 at 7.30pm in Nursling & Rownhams Village Hall, Nursling Street Council Members Present: Cllr P Bundy,Chairman Cllr M Maltby Cllr S Williams Cllr J Rendell Cllr R Martin Cllr A Bulpit In Attendance: The Clerk: Bill Ashdown, Cllr Perry, 3 members of the public (Mrs Marina Stuart, Mr Terry Elliott, Mr Alan Ball), PC Trish Attwood and colleague. No. No. ITEM Action by 1. Apologies. Cllr Finlay, Cllr Martin, Cllr Lines, Cllr Harding, Cllr Richards, Cllr Hall, Cllr Anderdon, Caroline Nokes. 2. Declarations of Interests. None 3. To Receive and Approve the Minutes of the Full Meeting of the Council held on 10th February 2015. The minutes of the Full Meeting held on Tuesday 10th February 2015 were formally approved. Proposed by Cllr Williams, seconded by Cllr Bulpit and signed off by Cllr Bundy. All Members present agreed. 4. Adjournment for 10 Minute Public Question Time. 4.1 Mrs Stuart, Mr Ball and Mr Elliott attended to discuss the use of The Glebe for the combined Church May Festival. They were told that the Parish Council in principle agreed for the Glebe to be used. In order to go ahead, however, Health & Safety (Risk Assessments etc) will need to be in place at least three weeks before the event. NURSLING & ROWNHAMS PARISH COUNCIL 3RD MARCH 2015 PG. 59 No. No. ITEM Action by 5. -

Bridgemary School Wych Lane, Gosport, PO13 0JN

School report Bridgemary School Wych Lane, Gosport, PO13 0JN Inspection dates 30 April–1 May 2013 Previous inspection: Not previously inspected Overall effectiveness This inspection: Inadequate 4 Achievement of pupils Inadequate 4 Quality of teaching Inadequate 4 Behaviour and safety of pupils Requires improvement 3 Leadership and management Requires improvement 3 Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is a school that has serious weaknesses. Students do not make sufficient progress and Behaviour and safety require improvement. achieve standards that are below average in The new behaviour policy is making a too many subjects. difference, but there is still low-level disruption Achievement in science is inadequate in some lessons. A few students are not always because students do not make the amount of punctual or fail to attend school regularly. progress they should. The quality of leadership and management The science curriculum does not meet the requires improvement. The headteacher, needs of all students, particularly the more governors and other leaders have a clear focus able. on what is required to improve the quality of Too much teaching is inadequate or requires teaching and students’ achievement. New improvement. Work does not take account of policies and procedures are not yet applied students’ different abilities. Teachers do not consistently by all staff, which is slowing the always expect enough of students. As a drive for improvement. result, students achieve poor results that do not reflect their capabilities. The school has the following strengths Students are given good advice and guidance The school has effective systems for about the subjects that they chose to study. -

Winchester Museums Service Historic Resources Centre

GB 1869 AA2/110 Winchester Museums Service Historic Resources Centre This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 41727 The National Archives ppl-6 of the following report is a list of the archaeological sites in Hampshire which John Peere Williams-Freeman helped to excavate. There are notes, correspondence and plans relating to each site. p7 summarises Williams-Freeman's other papers held by the Winchester Museums Service. William Freeman Index of Archaeology in Hampshire. Abbots Ann, Roman Villa, Hampshire 23 SW Aldershot, Earthwork - Bats Hogsty, Hampshire 20 SE Aldershot, Iron Age Hill Fort - Ceasar's Camp, Hampshire 20 SE Alton, Underground Passage' - Theddon Grange, Hampshire 35 NW Alverstoke, Mound Cemetery etc, Hampshire 83 SW Ampfield, Misc finds, Hampshire 49 SW Ampress,Promy fort, Hampshire 80 SW Andover, Iron Age Hill Fort - Bagsbury or Balksbury, Hampshire 23 SE Andover, Skeleton, Hampshire 24 NW Andover, Dug-out canoe or trough, Hampshire 22 NE Appleshaw, Flint implement from gravel pit, Hampshire 15 SW Ashley, Ring-motte and Castle, Hampshire 40 SW Ashley, Earthwork, Roman Building etc, Hampshire 40 SW Avington, Cross-dyke and 'Ring' - Chesford Head, Hampshire 50 NE Barton Stacey, Linear Earthwork - The Andyke, Hampshire 24 SE Basing, Park Pale - Pyotts Hill, Hampshire 19 SW Basing, Motte and Bailey - Oliver's Battery, Hampshire 19 NW Bitterne (Clausentum), Roman site, Hampshire 65 NE Basing, Motte and Bailey, Hampshire 19 NW Basingstoke, Iron -

Archaeological Excavations at Leigh Park, Near Havant, Hampshire, 1992

Proc Hampsh Field Club & Archaeol Soc, Vol 51, 1995, 201-232 201 ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS AT LEIGH PARK, NEAR HAVANT, HAMPSHIRE 1992 By CK CURRIE with a contribution by CLARE DE ROUFFIGNAC ABSTRACT HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Excavations were carried out on the extensive landscape gardensThe earlier landscape around Leigh Park had of Sir George Staunton at Leigh Park, near Havant. The resultsstrong connections with medieval stock pasturing indicated an earlier beginning to elements of the designed in Havant Thicket and the Royal Forest of Bere landscape than previously considered. Walled gardens and other(Pile 1989, 13). It would appear that the features already existed before an earlier owner, William gardener's cottage, the farm and Leigh House, Garrett's, time (c 1802—19). Both Garrett and Staunton plus other houses now vanished, formed the (1802-59) added considerably to the landscape design. During this period, a hamlet with possible medieval, and earlier, origins hamlet of West Leigh. This small settlement of was swept away. A good assemblage of seed remains from both approximately six separate houses is shown on an the medieval and designed landscape phases was recovered that undated map which research has dated to adds a further dimension to our knowledge of the site. c 1792-1800 (HRO 124M71 E/Pl). These cottages were either incorporated into the estate by Staunton's time, or had been demolished. INTRODUCTION The first mention of a house on the site of Leigh House dates from 1767 when a Charles Webber Leigh Park, near Havant, Hampshire stands on the purchased the reversionary right to a messuage, northern edge of the Leigh Park Housing Estate barn and gateroom, together with nine acres of (NGR SU 721 086) (Fig 1).