Archaeological Desk Based Assessment | 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Church of St Peter, South Weald PARISH PROFILE

Parish Church of St Peter, South Weald PARISH PROFILE SEPTEMBER 2015 Our Church St Peter’s Church is in the village of South Weald on the outskirts of Brentwood, to the east of the M25 and the London Borough of Havering. It is a lively and flourishing church with a congregation encompassing all ages. Our services are middle of the road but there is a wide range of churchmanship within the congregation and our doors are open to all. More than half of the Electoral Roll live outside the parish. Our Voluntary Aided Primary School in the village has been rated as outstanding in all respects. We are fortunate to have a vibrant and diverse congregation, including a large number of young families. While many start to attend church in order to meet attendance criteria for admission to local church schools, our welcoming and accepting attitude means that a number become committed members of the congregation. Our challenge is to respect the needs of our long-standing members whilst engaging with newcomers. St Peter’s Rule of Life As followers of Christ, we aim: to attend worship regularly, including Holy Communion; to maintain a pattern of daily prayer and develop our spiritual lives; to read and study the Bible; to help grow the church community through our time, talents and money; to assist others and to serve the needs of the local community; to have a concern for the whole world and to work for the coming of God’s kingdom; 1 to share our faith through action and word. -

Archaeological Monitoring at Tilty Hill Barn, Cherry Street, Duton Hill, Great Dunmow, Essex, CM6 2EE March 2018

Archaeological monitoring at Tilty Hill Barn, Cherry Street, Duton Hill, Great Dunmow, Essex, CM6 2EE March 2018 by Dr Elliott Hicks with contributions by Stephen Benfield figures by Ben Holloway and Sarah Carter fieldwork by Mark Baister commissioned by Patricia Wallbank on behalf of Mrs Fi McGhee-Perkins NGR: TL 5967 2748 (centre) Planning reference: UTT/17/2246/FUL & UTT/17/2247/LB CAT project ref.: 18/02d Saffron Walden Museum accession code: SAFWM 2018.3 ECC code: TYTH18 OASIS reference: colchest3-308709 Colchester Archaeological Trust Roman Circus House Roman Circus Walk, Colchester, Essex CO2 7GZ tel.: 01206 501785 email: [email protected] CAT Report 1261 May 2018 Contents 1 Summary 1 2 Introduction 1 3 Archaeological background 1 4 Aims 2 5 Results 2 6 Finds 4 7 Conclusion 5 8 Acknowledgements 5 9 References 5 10 Abbreviations and glossary 5 11 Contents of archive 6 12 Archive deposition 6 Figures after p6 Appendix 1 OASIS Summary List of maps, photographs and figures Cover: general site shot Map 1 Extract from Chapman and André map of Essex, 1777 2 Photograph 1 Site shot – looking south-west 3 Photograph 2 F1 – looking north 3 Photograph 3 Pottery bases 4 Fig 1 Site location Fig 2 Monitoring results Fig 3 Representative sections CAT Report 1261: Archaeological monitoring at Tilty Hill Barn, Cherry Street, Duton Hill, Great Dunmow, Essex – March 2018 1 Summary Archaeological monitoring was carried out at Tilty Hill Barn, Cherry Street, Duton Hill during a single-storey side extension associated groundworks. Remains associated with the historic farmstead which previously stood at this site, a concrete yard surface and two bricks dating to the post-medieval or modern periods, were uncovered. -

2013 CAG Library Index

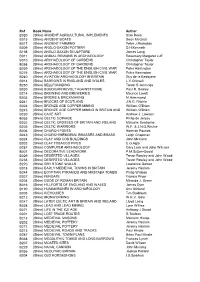

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This Collection Was the Gift of Howard J

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This collection was the gift of Howard J. Garber to Case Western Reserve University from 1979 to 1993. Dr. Howard Garber, who donated the materials in the Howard J. Garber Manuscript Collection, is a former Clevelander and alumnus of Case Western Reserve University. Between 1979 and 1993, Dr. Garber donated over 2,000 autograph letters, documents and books to the Department of Special Collections. Dr. Garber's interest in history, particularly British royalty led to his affinity for collecting manuscripts. The collection focuses primarily on political, historical and literary figures in Great Britain and includes signatures of all the Prime Ministers and First Lords of the Treasury. Many interesting items can be found in the collection, including letters from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning Thomas Hardy, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, King George III, and Virginia Woolf. Descriptions of the Garber Collection books containing autographs and tipped-in letters can be found in the online catalog. Box 1 [oversize location noted in description] Abbott, Charles (1762-1832) English Jurist. • ALS, 1 p., n.d., n.p., to ? A'Beckett, Gilbert A. (1811-1856) Comic Writer. • ALS, 3p., April 7, 1848, Mount Temple, to Morris Barnett. Abercrombie, Lascelles. (1881-1938) Poet and Literary Critic. • A.L.S., 1 p., March 5, n.y., Sheffield, to M----? & Hughes. Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon (1784-1860) British Prime Minister. • ALS, 1 p., June 8, 1827, n.p., to Augustous John Fischer. • ANS, 1 p., August 9, 1839, n.p., to Mr. Wright. • ALS, 1 p., January 10, 1853, London, to Cosmos Innes. -

Great Easton Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals, 2014

Great Easton Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals, Approved June 2014 Great Easton Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals, 2014 Contents 1 Part 1: Appraisal 3 Introduction 3 Planning Legislative Framework 4 Planning Policy Framework 6 The General Character and Setting of Great Easton 7 Origins and Historic Development 9 Character Analysis 11 Great Easton village 14 1 Part 2 - Management Proposals 29 Revised Conservation Area Boundary 29 Planning Controls and Good Practice: The Conservation Area 29 Planning Controls and Good Practice: The Potential Need to Undertake an Archaeological Field Assessment 29 Planning Control and Good Practice: Listed Buildings 29 Planning Controls and Good Practice: Other Buildings that Make an Important Architectural or Historic Contribution 29 Planning Controls and Good Practice: Other Distinctive Features that Make an Important Architectural or Historic Contribution 30 Planning Control and Good Practice: Important Open Spaces, Trees and Groups of Trees 30 Proposed Controls: Other Distinctive Features that make an Important Visual or Historic Contribution 30 Enhancement Proposals to Deal with Detracting Elements 31 1 Maps 32 Figure 1 - 1877 Ordnance Survey Map 32 Fig 2 - Character Analysis 33 Character Analysis Key 34 Figure 3 - Management Plan 35 Management Plan Key 36 1 Appendices 37 Appendix 1 - Sources 37 Great Easton Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals, 2014 3 Part 1: Appraisal 1 Introduction 1.1 This appraisal has been produced by Officers of Uttlesford District Council to assess the current condition of the Great Easton Conservation Area, to identify where improvements can be made and to advise of any boundary changes that are appropriate. -

Document-0.Pdf

A N EXQ UISIT E COLLECT ION OF 29 BEAUTIFU L HOMES Thaxted is a magnificent Medieval town sat in the heart of Uttlesford District, Essex. Home to the distinguished the Guildhall, eminent Thaxted Church and the restored John Webb’s Windmill. Set against a backdrop of exquisite architecture Thaxted is considered to be the jewel in the crown of Essex. whittles Thaxted is a small country town with a recorded history which THAXTED dates back to before the Domesday Book. The town is resplendent in architectural interest, unique in character with a flourishing community. The town remains today what it has been for the last ten centuries - a thriving town which moves with the times, but also embraces its heritage with admirable respect. 2 Images depict local area. 3 4 A CHARMED INTIMACY Although Thaxted is a small town it satisfies the needs of modern living with the charmed intimacy one would expect from Essex’s jewel in the crown. As well as being equipped with the day to day conveniences of a post office, pharmacy, library and village shop, Thaxted offers so much more. The Star is a 15th century Inn which has now been refurbished into a modern, stylish and elegant eatery and The Swan and Maypole public houses, offer an abundance of real ales and local joviality. Just a short walk from The Whittles is Ocean Delight, a good old fashioned fish and chips shop and if you continue further into town you could experience the delectable Indian cuisine of India Villa. Thaxted also has an abundance of outside spaces; the recreation ground features a playing field, a basketball and netball court and a children’s playing area. -

ESSEX. • Smith Mrs

TRADES DIRECTORY.] .FAR 469 ESSEX. • Smith Mrs. Edward, Link farm, West Smith Mrs. Thos. Mudwall, DunmowS.O Spooner Samuel, Steeple, Maldon Hanningfield, Chelmsford Smith WaIter, Blamsters hall, Great Sprigett Jsph. Castle Hedinghm.Hlstead Smith Mrs. Elizabeth, Bardfield hall, Easton, Dunmow Springett James, Gt. Braxted, Witham Great Bardfield, Braintree Smith William, Byron house, Galley- Spurge John, Cooper's Hill house, High Smith F. Spurrier, High Ongar, Ingtstne wood common, Chelmsford Ongar, Brentwood Smith Frederick John, Colliers wood, Smith Wm. Great Chishall, Royston Spurgeon Charles, Broxted, Dunmow8.0 Ardleigh, Colchester Smith Wm. Great Leighs, Chelmsford Spurgeon Obadiah, Woodgates, Broxted, Smith Frederick William, Mocken Herds Smith Wm. Little Bedfords, Havering- Dunmow S.O farm, Barnston, Chelmsford atte-Bower, Romford Squier S. W. Horndon-on-the-Hill,Rmfrd Smith G. Bowsers, Ashdon, Cambridge Smith Wm.Market farm, Old Sampford, Squier Wm. Dunton Hill's farm, East Smith G. Coxtie gm. Sth.Weald, Brntwd Braintree Horndon, Brentwood Smith G. Maidens, High Easter, Chmsfrd Smith W. New ho. Stambourne, Hlstead Squires Charles,Blanketts farm, Childer~ Smith Geo. Purples, Lit. Saling,Braintree SmoothyH. Birdbrk. hall,Brdbrk. Hlsted ditch, Brentwood Smith George Shoobridge, Kings, Little Snape F. Boarded barns,Shelley, Brntwd Staines Albert, Warwicks, White Rooth~ Easton, Dunmow . SnapeF.The Wonts, High Ongar,Brntwd ing, Chelmsford Smith Henry, Place farm, Great Bard- Snow Mrs. A. Martells, Dunmow S.O Staines George, Ray Place farm, Black~ field, Braintree Snow J. Gt. Hallingbury, Bp.'sStortford more, Brentwood Smith Henry, Salcott, Kelvedon Snow John, Mill house, Dunmow S.O Staines Miss M. A.Maldon Wick., Maldon Smith H. C. Stebbing green, Chelmsford Snow Peter, Long's farm, Little Wal- Staines Mrs. -

Essex. Ins 485 E

TRADES DIRECTORY.] ESSEX. INS 485 E. N. Palmer, High street, collector) Saffron Walden Hospital (A. N. Jones, HURDLE MAKERS. (open on tuesday&friday at 10 a.m.),1 H.Stear&H.J.Buck,medicalofficers; B k ttPhir Gl be ad T wnfi Id Moulsham, Chelmsford John Gelling,dispenser;ArthurMidg- ec e lIDon, e ro ,0 e Children's Hospital Home (Mrs.Elizabeth ley, sec. ; Mrs. BerniceWinter,matron), B ~:eeiIChelm~ford h ad R mf rd RadIord, matron), 7 Brandon road, London road, Saffron Walden ~ ge enry, agen am.ro , 0 0 Walthamstow St. Edward's Catholic Reformatory Bridge Mrs. Jane, Havermgwell, Hom~ Convent of Jesus & Mary,Stratfrd. gm e (Dominique Kemp, director; Rev. church, Romford Coope's (Mrs.) Home (Mrs.Janet Carden, Jsph. Zsilkay, chaplain), Green street, Butcher James, ~t Easton, Dunmow matron), Crescent road, Brentwood Plashet e Butcher ~ohn, Tilty, Chelmsford . Deaconesses Institution (Miss Sealy, lady St. James' Orphanage (Miss Caroline Clarke RIChard, Corbets Tey, Upmmster, supt.), 73 Romford road, Stratford e C. Jones, matron), East hI. Colchester Romford Diocesan House of Mercy for Fallen St. John's Nursery (B. R. Cant, pro- H.oward Joseph, Elmstead, Colch~ter Women (Rev. Charles Hy. Cope M.A. prietor), Greenstead, Colchester & L~coln John,Thundersley,RayletghS.O warden; Miss Dorothy Walker, lady St. John's street, Colchester Lmnett G: Runsell, Danbury, Chelmsfrd superior), Great Maplestead, Halstead St. Mary of Egypt's Home (Miss Sophia Maryon Richard, Mo~ton, Brentwood East-End Juvenile Mission Home for Ingersole, superioress), Water lane, Pratt.Thoma~, Matchmg, Harlow Neglected & Destitute Girls ('rhos. Jas. Stratford e PrentICe DaVld, Moreton, Brentwood Barnardo 11.D. -

Geology of London 1922.Pdf

F RtCELEY PR ART (JNIVERSI-.Y Of EARTH CALIFORNIA SCIENCES LIBRARY MEMOIRS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SUEVEY. ENGLAND AND WALES. THE GEOLOGY OF THE LONDON DISTRICT. (BEING THE AREA INCLUDED IN THE FOUR SHEETS OF THE SPECIAL MAP OF LONDON.) BY HORACE B. WOODWARD, F.R.S. SECOND EDITION, REVISED, BY C. E. N. BROMEHEAD, B.A., WITH NOTES ON THE PALAEONTOLOGY, BY C. P. CHATWIN. PUBLISHED P.Y ORDER OF THE LORDS COMMISSIONERS OF HIS MAJESTY'S TREASURY. ' LONDON: PRINTED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased from E. STANFORD, LTD., 12, 13, and 14, LONG ACRE, LONDON, W.C. 2; A. W. & K. JOHNSTON, LTD., 2, ST. ANDREW SQUARE, EDINBURGH ; HODGES, FIGGIS & Co., LTD., 20, NASSAU STREET, and 17 & 18, FREDERICK STREET, DUBLIN ; or from for the sale of any Agent Ordnance Survey Maps ; Qr through any Bookseller, from the DIRECTOR-GENERAL, ORDNANCE SURVEY OFFICE. SOUTHAMPTON. 1922. Price Is. Sd.^Net. MEMOIRS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SUEVET. ENGLAND AND WALESi V THE GEOLOGY OF THE LONDON DISTRICT. (BEING THE AREA INCLUDED IN THE FOUR SHEETS OF THE SPECIAL MAP OF LONDON.) BY HORACE B. WOODWARD, F.R.S. M SECOND EDITION, REVISED, BY C. E. N. BROMEHEAD, B.A., WITH NOTES ON THE PALAEONTOLOGY, BY C. P. CHATWIN. PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE LORDS COMMISSIONERS OF HIS MAJESTY'S TREASURY. LONDON: FEINTED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased from E. STANFORD, LTD., 12, 13, and 14, LONG ACRE, LONDON, ^.C. 2; W. & A. K. JOHNSTON, LTD., 2, ST. ANDREW SQUARE, EDINBURGH ; HODGES, FIGGIS & Co., LTD., 20, NASSAU STREET, and 17 & 18, FREDERICK STREET, DUBLIN; or from for the sale of any Agent Ordnance Survey Maps ; or through any Bookseller, from the DIRECTOR-GENERAL, ORDNANCE SURVEY OFFICE. -

Parish Profile

Parish Profile An invitation to lead the Pilgrim Parishes as our Priest The Pilgrim Parishes Parish Profile Contents SUMMARY OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................... 2 1. THE PERSON WE SEEK .............................................................................................. 3 2. INTRODUCING OURSELVES ...................................................................................... 7 3. OUR MINISTRY ...................................................................................................... 11 4. OUR MISSION & COMMUNITY PRESENCE ............................................................... 17 5. OUR ADMINISTRATION & FINANCES ...................................................................... 23 6. OUR BUILDINGS & PROPERTIES .............................................................................. 25 APPENDIX ........................................................................................................................... 33 Issue 1.0 1 of 38 The Pilgrim Parishes Parish Profile SUMMARY OVERVIEW The Pilgrim Parishes was set up in 2016 when two rural benefices to the north and east of Great Dunmow were joined under the oversight of a fulltime Priest-in-Charge. At present we are at an early stage of working together to become a combined benefice. With the Lord’s guidance we are seeking a new priest with vision and competence to encourage and build up effective mission and ministry to reach out and meet the needs of the people -

Essex, Herts, Middlesex Kent

POST OFFICE DIRECTORY OF ESSEX, HERTS, MIDDLESEX KENT ; CORRECTED TO THE TIME OF PUBLICATION. r LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY KELLY AND CO,, OLD BOSWELL COURT, ST. CLEMENT'S, STRAND. W.C. 1862. PREFACE. TIIE Proprietors, in submitting to their Subscribers and the Public the present (being the Fifth) Edition of the Six HOME COUNTIES DIRECTORY, trust that it may • be found to be equal in accuracy to the previous Editions. Several additions have been made to the present volume : lists of Hundreds and Poor Law Unions have been included in the Topography of each County; it is stated under each Parish in what Hundred, Union and County Court District it is situate, as well as the Diocese, Archdeaconry and Rural Deanery; and the College and University of every Beneficed Clergyman have been given. The Post Office Savings Banks have been noticed; the names of the Parish Clerks are given under each Parish ; and lists of Farm Bailiffs of gentlemen farming their own land have been added. / The bulk of the Directory has again increased considerably: the Third Edition consisted of 1,420 pages; the Fourth had increased to 1,752 pages; and the present contains 1,986 pages. The value of the Directory, however, will depend principally on the fact that it has been most carefully corrected, every parish having been personally visited by the Agents during the last six months. The Proprietors have again to return their thanks to the Clergymen, Clerks of the Peace, Magistrates' Clerks, Registrars, and other Gentlemen who have assisted the Agents while collecting the information. -

Broker List for Mortgage Prisoners

Broker List for Mortgage Prisoners East England Firm name Firm address Firm phone number Firm email Abode Mortgages Limited 14 Bateman Road Brightlingsea Colchester Essex 01206 252025 [email protected] CO7 0SG Agentis Financial & Mortgage Solutions Ground Floor, 36 Thorpe Wood, Peterborough, 07590039956 [email protected] Ltd PE3 6SR AMAS Investments Mill House, Bridges Walk, Thetford, IP24 2EF 01842 752140 [email protected] AMS Financial Services Ltd 75 St Marys Drive, South Benfleet, Essex, SS7 1LH 07710123867 [email protected] Assured Mortgage Advice 152 Great North Road, East Socon, St. Neots, 01480473084 [email protected] Cambridgeshire, PE19 8GS Barrett Batchelor Mortgage Services LLP Suite 203, 27 Tuesday Market Place, King's Lynn, 01553692800 [email protected] Norfolk, PE30 1JJ Barrie Hough Financial Services Limited 9 Lords Court, Basildon, Essex, SS13 1SS 01782836421 [email protected] Cambridgeshire Money Ltd 37 High Street, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, 01733 736205 [email protected] PE29 3AQ County Mortgage Services Ltd Moulsham Mill, Parkway, Chelmsford, Essex, CM2 01245268204 [email protected] 7PX DST Financial Servs Ltd 9 Princes Street, Norwich, NR3 1AZ 01603499060 [email protected] Fidelity Mortgages Ltd Suites 1 & 2, 2nd Floor, Lingwood House, The 01375267222 [email protected] Green, Stanford-Le-Hope, SS17 0EX Four Financial Suite3, 200 London Road, Southend On Sea, 07814411992 [email protected] Essex, SS1 1PJ KDW Financial Planning