ANPS Occasional Paper No 10 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLV Chinese Language Lessons Sen Lin Hu Chinese Language Camp Lessons for the Classroom

CLV Chinese Language Lessons Sen Lin Hu Chinese Language Camp Lessons For the Classroom Date: Class: Chinese Language Level: Novice High Grade High School Day in 1 Minutes 70 Unit Geography of China: How is my experience in China influenced by where I am? Unit Theme and Question: STAGE 1: What will learners be able to do with what they know by the end of this lesson? DO KNOW What are the learning targets for this lesson? What vocabulary, grammatical structures, language chunks, cultural knowledge, and content information do learners need to accomplish the lesson can-do? Learners will be able to: • Vocabulary: 沙漠, 高原, 高山, 小山, 河流, 森林, • Compare the shape of China to a rooster. 草原, 大海, 耕地(农田),公鸡 • Recognize and name 9 main geographical features of China: • Culture: Geographical location of landforms in China desert, mountains, hills, ocean, grassland, farmland, plateau, • Radicals: 木,艹, 水 forest, river. • Sentence structures: 在 中国(direction)有 ——。 • Locate these geographical features on a map of China • Identify 3 radicals in characters related to geography 在中国西北有沙漠和高原。 • Form sentences describing the locations of landforms (In China’s northwest there is desert, and high plateau.) STAGE 2: How will learners demonstrate what they can do with what they know by the end of the lesson? What will learners do (learning tasks/activities/formative assessments) to demonstrate they can meet the lesson can-do? Learners will: • select from multiple possibilities which animal is represented in the shape of China • name 9 landforms found in China, match -

49 Chapter 5 Topographical Maps

Topographical Maps Chapter 5 Topographical Maps You know that the map is an important geographic tool. You also know that maps are classified on the basis of scale and functions. The topographical maps, which have been referred to in Chapter 1 are of utmost importance to geographers. They serve the purpose of base maps and are used to draw all the other maps. Topographical maps, also known as general purpose maps, are drawn at relatively large scales. These maps show important natural and cultural features such as relief, vegetation, water bodies, cultivated land, settlements, and transportation networks, etc. These maps are prepared and published by the National Mapping Organisation of each country. For example, the Survey of India prepares the topographical maps in India for the entire country. The topographical maps are drawn in the form of series of maps at different scales. Hence, in the given series, all maps employ the same reference point, scale, projection, conventional signs, symbols and colours. The topographical maps in India are prepared in two series, i.e. India and Adjacent Countries Series and The International Map Series of the World. India and Adjacent Countries Series: Topographical maps under India and Adjacent Countries Series were prepared by the Survey of India till the coming into existence of Delhi Survey Conference in 1937. Henceforth, the preparation of maps for the adjoining 49 countries was abandoned and the Survey of India confined itself to prepare and publish the topographical maps for India as per the specifications laid down for the International Map Series of the World. -

The Relevance of Spatial Relation Terms and Geographical Feature Types

The Relevance of Spatial Relation Terms and Geographical Feature Types Chunju Zhang Xueying Zhang Key Laboratory of Virtual Geography Environment (Nanjing Normal University), MOE, Nanjing, China [email protected] Abstract: Spatial relation terms can generally indicate spatial relations de- scribed in natural language context. Their semantic representation is closely re- lated to geographical entities and their characteristics e.g. geometry, scale and geographical feature types. This paper proposes a quantitative approach to ex- plore the semantic relevance of spatial relation terms and geographical feature types of geographical entities in text. Firstly, a classification of spatial relation terms is performed. Secondly, the “Overlap” similarity measure is introduced to define the relevance of spatial relation terms and geographical feature types based on a large scale annotation corpus. Finally, a knowledge base based on protégé is developed to formally represent and visualize geographical feature types, spatial relation classifications, and the relevance of spatial relation terms and geographical feature types. This study indicates that spatial relation terms are strongly relevant to geographical feature types. The semantic representation of topological relation terms is diverse and their relevance with geograph- ical feature types is much stronger than directional relation and distance rela- tion terms, but the annotation quality and the classification granularity of geo- graphical entities in the corpus have a great effect on the performance. Keywords: spatial relation; geographical feature type; spatial relation term; relevance 1 Introduction Natural language describes the nature of people’s internal representation of space and is the primary means for representation and exchange of geographical infor- mation, such as geographical entities, spatial relations, etc. -

Geography of Coachella Valley Curriculum Guide

Exploring the Geography of Coachella Valley A Curriculum Guide for Grade 3, Standard 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements i Table of Contents 1 Unit Overview 2 Common Core State Standards: Reading Standards for Information Text 2 Academic History-Social Science Content Standards for Grade 3 2 Kindergarten to Grade 5 Historical and Social Sciences Analysis Skills 3 Focus Questions and Assessment 3 Geography of the Coachella Valley – Background Information for the Teacher 4 Supplies Needed 6 Lesson 1: Location Match-Up 8 Lesson 2: Looking at Earth 11 Lesson 3: Where I Live 14 Lesson 4: Geographic Terms and Definitions 16 Lesson 5: Right Here in the Coachella Valley 20 Lesson 6: Geographical Features of Coachella Valley 24 Lesson 7: Human-Made Features of Coachella Valley 29 Lesson 8: Communityville 31 Extended Activities 39 Unit 3.1 Exploring the Geography of Coachella Valley Page 1 Unit Overview: Exploring the Geography of Coachella Valley __________________________________________________________________________________ Description of the Unit The unit begins with Matching Vocabulary Cards that help students learn the name of their city, county, state, nation, continent, hemisphere, and planet. In Lesson 2, students use a variety of maps to find these geographic locations while in Lesson 3 they construct a “Flip-Book” titled “Where I Live.” In Lessons 4 and 5, students study geographic terms and definitions and use local maps to identify key geographical features in the Coachella Valley. In Lessons 5 and 6, students construct a map of the Coachella Valley and identify key geographical features and human-made features. The focus in Lesson 8 is on how the natural environment of “Communityville” has been changed over time. -

An Evaluation Model of Level of Detail Consistency of Geographical Features on Digital Maps

International Journal of Geo-Information Article An Evaluation Model of Level of Detail Consistency of Geographical Features on Digital Maps Pengcheng Liu 1,2 and Jia Xiao 1,2,* 1 Hubei Province Key Laboratory for Geographical Process Analysis & Simulation, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, China; [email protected] 2 College of Urban and Environmental Science, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-157-0299-4209 Received: 29 May 2020; Accepted: 24 June 2020; Published: 26 June 2020 Abstract: This paper proposes a method to evaluate the level of detail (LoD) of geographic features on digital maps and assess their LoD consistency. First, the contour of the geometry of the geographic feature is sketched and the hierarchy of its graphical units is constructed. Using the quartile measurement method of statistical analysis, outliers of graphical units are eliminated and the average value of the graphical units below the bottom quartile is used as the statistical LoD parameter for a given data sample. By comparing the LoDs of homogeneous and heterogeneous features, we analyze the differences between the nominal scale and actual scale to evaluate the LoD consistency of features on a digital map. The validation of this method is demonstrated by experiments conducted on contour lines at a 1:5K scale and artificial building polygon data at scales of 1:2K and 1:5K. The results show that our proposed method can extract the scale of features on maps and evaluate their LoD consistency. Keywords: level of detail; graphical unit; geographical feature; digital map 1. -

Generic Terms in the Canadian Geographical Names Database

GEGN.2/2021/59/CRP.59 18 March 2021 English United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names 2021 session New York, 3 – 7 May 2021 Item 11 of the provisional agenda * Toponymic Terminology Generic terms in the Canadian Geographical Names Database Submitted by Canada** Summary: A primary objective of the 2020–2025 strategic plan for the Geographical Names Board of Canada is to improve the content and the management of the Canadian Geographical Names Database. Generic terminology goes hand in hand with geographical naming. It is essential for the organization and classification of geographical names. The Board’s secretariat and the Translation Bureau, Public Services and Procurement Canada, are working together to conduct a full examination of all the generic terms representing geographical features in the Database, including their definitions, organization and current relevance. This is no small feat, given that there are more than 1,400 generic terms in the Database. The Board will review and draft: • The generic code classification, concise code classification, category and subcategory and their organization. • Plural forms of the generic terms (e.g., Lake vs. Lakes). The Translation Bureau, in collaboration with the Board’s secretariat, will: • Review terminology used in the generic definitions. • Organize the generic terms on the basis of a single-concept approach to meet International Organization for Standardization terminology standards. • Examine the feasibility of having a fully bilingual generic code list. The Board’s secretariat will examine the impact on Natural Resources Canada services, naming jurisdictions and the general public * GEGN.2/2021/1 ** Prepared by Kristina Kwiatkowski, Geographical Names Board of Canada Secretariat, Natural Resources Canada and Carolina Herrera, Translation Bureau, Public Services and Procurement Canada. -

Beyond Points: How to Turn SMW Into a Complete Geographic Information System Smwcon 2013, New-York

Beyond points: How to turn SMW into a complete Geographic Information System SMWCon 2013, New-York Pierre Racine Contributor to PostGIS Research Professional Center for Forest Research Québec, Canada Objectives • Demonstrate the need to support complex geometries in SMW. • Emphasis the need to store geometries natively in the DB. • Propose some geospatial functionalities. • Discuss how to transpose common GIS concepts into SMW. Semantic Mediawiki isisis a Database • Meaningful data and types • Queries • More than a database, it is a web data management system – Forms for input and edition. – Display and presentation of data (wikitext and template). – Possible to develop data driven web applications without having to write low level code (PHP, Ruby, Java, Python, etc…) Semantic Maps isisis a SSSpatialSpatial DDDatabaseDatabase • A spatial database – Has special types to store complex geographical entities. – Provide functions to manipulate and query spatial entities. • Semantic Maps can store points (geographic coordinates) – Human constructions (towns, villages, building, etc…). – Geographic features (peaks, falls, islands, etc…). – Events (shows, conferences, scientific observations, etc…). – Moving objects (trucks, plane, boats, cars). • Queries – By any attributes returning a geographic coordinate. – By distance to a specific coordinate. • Display as maps – Basemaps: Google Map, OpenLayers and OpenStreetMap. • Forms – Map allowing to point to generate a geographic coordinate. • Perfect to create what we call a Web GIS application! • But the world is not made just of points… What’s missingmissing? ? 1) Types for representing complex geographic entities • Professional spatial databases allows storing more complex geometries • LineStrings & MultiLineString – Roads, rivers, transmission lines, plane, boat or human trajectories or directions, contour lines, etc… • Polygons & MultiPolygons – Administrative limits (countries, states, agglomerations, postal codes). -

A Cartographic Data Model for Better Geographical Visualization Based on Knowledge

A CARTOGRAPHIC DATA MODEL FOR BETTER GEOGRAPHICAL VISUALIZATION BASED ON KNOWLEDGE Yang MEIa, *, Lin LIa aSchool Of Resource And Environmental Science, Wuhan University,129 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430079, China – [email protected], [email protected] WG II/5 KEY WORDS: Visualization, Cartography, Cartographic Knowledge, Cartographic Data Model, Cartographic Representation, Cartographic Symbol ABSTRACT: Firstly, this paper makes analyses on the geographical visualization and mapping functionality in GIS software which have some shortcomings. So, the idea of geographical information cartographic representation is presented to improve the quality of the geographical information visualization and to satisfy rules of traditional cartography. The digital cartographic representation, which tries to make a model of the mapping procedure based on traditional cartographic knowledge, creates a template-mapping model for cartographic symbols. This template-mapping model achieves the transformation from cartographic specifications to products. Meanwhile, it can well consider characteristics of respective geographical feature, the relations between this feature and other features, the relations between this feature and cartographic region. These three kinds of relations are described with quantity parameters which can be used to map a symbol template to a symbol instance responding to some one geographical feature. With this template-mapping model for cartographic symbol, we can visualize the respective feature’s property in detail and improve the quality of geographical visualization. Hydrology and transportation features are taken as two examples to verify the availability of this cartographic representation model. 1. INTRODUCTION Geographical information visualization is the combination of geographical information representation and scientific Maps are the essential tools for geographical information visualization. The fundamental type of the geographical visualization. -

Mapping the Mississippi

R E S O U R C E L I B R A R Y A C T I V I T Y : 1 H R Mapping the Mississippi Students explore the physical and social characteristics of the Mississippi River through Internet-based research and an interactive map to measure and analyze the river's geography. They compare these methods of investigation to understand the benefits of different types of learning resources. G R A D E S 6 - 12+ S U B J E C T S Earth Science, Experiential Learning, Geography, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Human Geography, Physical Geography C O N T E N T S 3 Links, 2 PDFs OVERVIEW Students explore the physical and social characteristics of the Mississippi River through Internet-based research and an interactive map to measure and analyze the river's geography. They compare these methods of investigation to understand the benefits of different types of learning resources. For the complete activity with media resources, visit: http://www.nationalgeographic.org/activity/mapping-mississippi/ DIRECTIONS 1. Research the physical and human characteristics of the Mississippi River. Explain to students that they will explore the Mississippi River and its watershed in two ways: through Internet research and with an interactive map called FieldScope. Have students work at computers individually, in pairs, or in small groups if necessary. First, have students read the National Geographic encyclopedic entry for watersheds to build their understanding of what a watershed is. Introduce the Mississippi River watershed, explaining how it is a complex physical and geographical feature that has important ecological, social, and historical implications. -

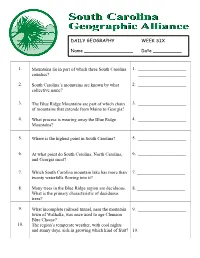

1. 2. Mountains Lie in Part of Which Three South Carolina Counties?

DAILY GEOGRAPHY WEEK SIX Name _________________ Date __________ 1. Mountains lie in part of which three South Carolina 1. _____________________ counties? _____________________ _____________________ 2. South Carolina’s mountains are known by what 2. _____________________ collective name? 3. The Blue Ridge Mountains are part of which chain 3. _____________________ of mountains that extends from Maine to Georgia? 4. What process is wearing away the Blue Ridge 4. _____________________ Mountains? 5. Where is the highest point in South Carolina? 5. _____________________ 6. At what point do South Carolina, North Carolina, 6. _____________________ and Georgia meet? 7. Which South Carolina mountain lake has more than 7. _____________________ twenty waterfalls flowing into it? 8. Many trees in the Blue Ridge region are deciduous. 8. _____________________ What is the primary characteristic of deciduous trees? 9. What incomplete railroad tunnel, near the mountain 9. _____________________ town of Walhalla, was once used to age Clemson Blue Cheese? 10. The region’s temperate weather, with cool nights and sunny days, aids in growing which kind of fruit? 10. _____________________ DAILY GEOGRAPHY WEEK SEVEN Name _________________ Date __________ 1. What geographical term means “at the foot of the 1. _____________________ mountains”? 2. Describe the Piedmont Region of South Carolina. 2. _____________________ 3. What is the geographical term for a large, low area 3. _____________________ of land between areas of high land? 4. Describe the soil in the Piedmont of South Carolina. 4. _____________________ 5. Native Americans in the Piedmont linked camps and 5. _____________________ resources and also traded along what route? 6. What important Piedmont Revolutionary War battle 6. -

Signs on Printed Topographical Maps, Ca

21 • Signs on Printed Topographical Maps, ca. 1470 – ca. 1640 Catherine Delano-Smith Although signs have been used over the centuries to raw material supplied and to Alessandro Scafi for the fair copy of figure 21.7. My thanks also go to all staff in the various library reading rooms record and communicate information on maps, there has who have been unfailingly kind in accommodating outsized requests for 1 never been a standard term for them. In the Renaissance, maps and early books. map signs were described in Latin or the vernacular by Abbreviations used in this chapter include: Plantejaments for David polysemous general words such as “marks,” “notes,” Woodward, Catherine Delano-Smith, and Cordell D. K. Yee, Planteja- ϭ “characters,” or “characteristics.” More often than not, ments i objectius d’una història universal de la cartografia Approaches and Challenges in a Worldwide History of Cartography (Barcelona: Ins- they were called nothing at all. In 1570, John Dee talked titut Cartogràfic Catalunya, 2001). Many of the maps mentioned in this about features’ being “described” or “represented” on chapter are illustrated and/or discussed in other chapters in this volume maps.2 A century later, August Lubin was also alluding to and can be found using the general index. signs as the way engravers “distinguished” places by 1. In this chapter, the word “sign,” not “symbol,” is used through- “marking” them differently on their maps.3 out. Two basic categories of map signs are recognized: abstract signs (geometric shapes that stand on a map for a geographical feature on the Today, map signs are described indiscriminately by car- ground) and pictorial signs. -

Just What Is SDTS and What Does It Really Need?

IJGIS Theme Issue on Interoperability, Volume 12 Number 4, June 1998, pp.403-425 ISSUES AND PROSPECTS FOR THE NEXT GENERATION OF THE SPATIAL DATA TRANSFER STANDARD (SDTS) AUTHORS David Arctur, Ph.D. (author for correspondence) Laser-Scan, Inc. 45635 Willow Pond Plaza, Sterling, Virginia, 20164-4457 USA [email protected] David Hair EROS Data Center, U.S. Geological Survey Sioux Falls, South Dakota, USA [email protected] George Timson Mid-Continent Mapping Center, U.S. Geological Survey Rolla, Missouri, USA [email protected] E. Paul Martin Rocky Mountain Mapping Center, U.S. Geological Survey Denver, Colorado, USA [email protected] Robin Fegeas National Mapping Division, U.S. Geological Survey Reston, Virginia, USA [email protected] KEYWORDS SDTS, OpenGIS, Object-Oriented, Data Sharing/Exchange, Standards SHORT TITLE Issues and Prospects for SDTS ISSN 1365-8816 IJGIS Theme Issue on Interoperability, Volume 12 Number 4, June 1998, pp.403-425 ISSUES AND PROSPECTS FOR THE NEXT GENERATION OF THE SPATIAL DATA TRANSFER STANDARD (SDTS) D. Arctur R. Fegeas, D. Hair, G. Timson, E. Martin Laser-Scan Inc. US Geological Survey ABSTRACT The Spatial Data Transfer Standard (SDTS) was designed to be capable of representing virtually any data model, rather than being a prescription for a single data model. It has fallen short of this ambitious goal for a number of reasons, which this paper investigates. In addition to issues that might have been anticipated in its design, a number of new issues have arisen since its initial development. These include the need to support explicit feature definitions, incremental update, value-added extensions, and change tracking within large, national databases.