Stories to Tell Protecting Australian Children’S Screen Content

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’S Eve 2018 – the Night Is Yours

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’s Eve 2018 – The Night is Yours. Image: Jared Leibowtiz Cover: Dianne Appleby, Yawuru Cultural Leader, and her grandson Zeke 11 September 2019 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2019. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 11 September 2019 and provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC continues to be the home and source of Australian stories, told across the nation and to the world. The Corporation’s commitment to innovation in both storytelling and broadcast delivery is stronger than ever, as the needs of its audiences rapidly evolve in line with technological change. Australians expect an independent, accessible public broadcasting service which produces quality drama, comedy and specialist content, entertaining and educational children’s programming, stories of local lives and issues, and news and current affairs coverage that holds power to account and contributes to a healthy democratic process. The ABC is proud to provide such a service. The ABC is truly Yours. Sincerely, Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chair Letter to the Minister iii ABC Radio Melbourne Drive presenter Raf Epstein. -

The Misrepresentation of Representation: in Defense of Regional Storytelling in Netflix's the New Legends of Monkey

The Misrepresentation of Representation: In Defense of Regional Storytelling in Netflix’s The New Legends of Monkey KATE MCEACHEN The 2018 Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC Me), Television New Zealand (TVNZ), and Netflix’s coproduction of the original series The New Legends of Monkey (2018) is a fantasy-based television series that reimagines Monkey (1978), a British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) dubbing of the Japanese television series Saiyūki 西遊記. Saiyūki was an adaptation of the historically significant Chinese novel Xiyou ji (Wu Cheng’en, 1592), known in English as Journey to the West. Monkey gained a cult following in Australia, New Zealand, and other international markets leading to the 2018 reboot The New Legends of Monkey, which, unlike Monkey, was released in the United States (Flanagan). This new iteration prompted cultural confusion from those largely unfamiliar with the preceding series, the contexts in which it was introduced to English-speaking viewers in Australia and New Zealand, or the cult response that resulted. This article presents the recent series with this background in mind and within the context of locally produced television in New Zealand, where The New Legends of Monkey was filmed. Analysis of online discussions exposes the interpretive differences arising from this lack of context regarding the show’s connection to Monkey and highlights the problems viewers face interpreting stories outside of their local production markets—an increasingly relevant problem as more regional productions become accessible to a wide range of audiences through transnational streaming services like Netflix. The 2018 The New Legends of Monkey television adaptation, produced by and for the Australian and New Zealand markets and co-produced for international KATE MCEACHEN is currently pursuing her Doctoral Degree in Cultural Studies at The University of Southern Queensland in Australia. -

Information About NAIDOC Week from The

ABC celebrates NAIDOC Week 2021 Posted Sun 27 Jun 2021, 6:00am Updated Tue 29 Jun 2021, 9:49am NAIDOC Week content and creativity on the ABC Throughout NAIDOC Week, which runs from 4 - 11 July, the ABC will showcase Indigenous storytelling across television, radio and online, including the premieres of arts documentaries Firestarter: The Story of Bangarra, on ABC TV and iview, Tuesday 6th July 8:30pm Premieres Tuesday 6 July at 8.30pm on ABC TV and iview. Firestarter tells the story of how three young Aboriginal brothers - Stephen, David and Russell Page - turned a newly born dance group into a First Nations cultural powerhouse. My Name is Gulpilil on ABC TV and iview, Sunday 11th July 8:30pm Dubboo: Life of a Songman on ABC TV Plus, Wednesday 7th July 9:00pm ABC iview's NAIDOC Week collection will also feature the world premieres of children's programs Red Dirt Riders and Tjitji Lullaby, alongside outstanding Indigenous-led content such as The Australian Dream, FREEMAN, Mabo, Mystery Road, Total Control, Redfern Now and performances by Bangarra Dance Theatre. Across ABC Local Radio and social media, the ABC will feature young Indigenous leaders and Elders in conversation about the NAIDOC Week theme of "Heal Country!". Radio National programs will explore Indigenous stories and issues, including Earshot’s feature on the battle over the Martuwarra Fitzroy River and insights from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander activists and creatives across Awaye!, Soul Search, The Book Show, The Stage Show, Blueprint for Living, Stop Everything! and The History Listen. ABC music networks' celebration of Indigenous talent includes ABC Classic's premiere of Deborah Cheetham's Woven Song, Double J’s Deadly Beats J Files and an extended version of triple j’s new First Nations music show Blak Out. -

ABC Careers Koori Mail NEWSPAPER Content Coordinator Job No: 501563

ABC Careers Koori Mail NEWSPAPER Content Coordinator Job no: 501563 Job no: 501563 CLIENT’S Work type: Ongoing Full Time PROOF Location: Sydney Categories: Administration/Support, Production/Content AD SIZE: • Be a part of Australia's independent national broadcaster WEB AD • Ultimo, Sydney: Convenient CBD location (near Central Station) • Permanent Full-time Position TOTAL INCLUDING • $68K - $75K Plus 15.4% Nominated Super 10% GST: The ABC strives for equity and diversity in the workplace, and to promote a culture of opportunity. Through its services the ABC seeks to represent, connect and engage with all of the Australian $150 community. In line with our focus on diversity, applications are strongly encouraged from Indigenous Australians, people from a range of cultural and linguistic backgrounds, people with disability and CLIENT: ABC LGBTIQ+ individuals. The ABC also aims to achieve a gender-balanced workforce. For more information on inclusive employee networks within the ABC please refer to ABC LinkedIn ATTENTION: and Life Page Michelle About ABC Entertainment & Specialist The Entertainment & Specialist team brings together the ABC’s drama, comedy, Indigenous, music, children’s, entertainment and factual content across television, radio and digital products and PLEASE CHECK THIS AD services, such as iview, ABC listen and associated websites, apps and podcasts. The team includes AND FAX BACK ANY the specialist genres of arts, science, education, religion and ethics. Entertainment & Specialist CHANGES WITH YOUR develops, produces, acquires and distributes Australian stories across ABC TV, ABC Kids, ABC ME CONFIRMATION TO the national networks of ABC Radio, ABC online and audio and video apps, to inform, educate and PROCEED ON entertain all Australians. -

Seven Network Ratings Report Week 44

31 October 2016 Seven Network Ratings Report Week 44: 23 October – 29 October 2016 Seven wins in primetime on combined audiences. - Seven’s broadcast platform of Seven + 7TWO + 7mate + 7flix combines to win primetime in total viewers on the combined audiences of all multiple channels. Seven wins in news. - Seven News leads Nine News. - Seven News – Today Tonight leads Nine News 6:30. Seven wins in breakfast television. - Sunrise leads Today. Seven wins in morning television. - The Morning Show leads Today Extra. Seven wins at 5:30pm. - The Chase leads Hot Seat. Seven wins in primetime on digital channels. - 7TWO is number 1 for total viewers. - 7mate is number 1 for 25-54s. Seven is number 1 in 2016 - Seven is number 1 for total viewers, 16-39s, 18-49s and 25-54s in primetime on primary channels across the current television season. - 7TWO is number 1 for total viewers in primetime on digital channels across the current television season. - 7mate is number for 18-49s and 25-54s in primetime on digital channels across the current television season. Seven + 7TWO + 7mate + 7flix is number 1 in 2016 - Seven’s broadcast platform of Seven + 7TWO + 7mate + 7flix is number 1 in primetime in total viewers, 16-39s, 18-49s and 25-54s on the combined audiences of all multiple channels across the current television season. Seven wins in breakfast television and morning television across Australia. - Sunrise = 546,000 vs Today = 462,000 - The Morning Show = 251,000 vs Today Extra = 184,000 - Metropolitan and Regional Combined Audiences Seven delivers in the most-watched programmes across Australia. -

Bluey Fetches a Second Series As the Smash Hit Achieves Over 75 Million Plays and Counting

RELEASED: THURSDAY 16 MAY 2018 Bluey fetches a second series as the smash hit achieves over 75 million plays and counting Cementing Bluey as the #1 series ever on ABC iview* Families across Australia have asked for more Bluey, and we’re happy to announce more is on the way! Created by Joe Brumm, Bluey is produced by the Emmy® award-winning Ludo Studio for ABC KIDS and is co-commissioned by ABC Children’s and BBC Studios. Financed in association with Screen Australia, Bluey is proudly 100% created, written, animated and post produced in Brisbane Queensland, Australia, with funding from The Queensland Government through Screen Queensland and the Australian Government. The second series of Bluey will continue to celebrate our distinctively Australian family and the role of imaginative play in shaping children’s lives. Bluey will play fun and elaborate new games with her sister Bingo; Chilli’s relationship with her girls will be further explored as she juggles work and family life; Bandit returns with his wry sense of humour; and we’ll meet more of Bluey and Bingo’s family and friends. This true-blue Australian series is created by creator/showrunner Joe Brumm (Charlie and Lola), Emmy® awarding-winning executive producers Charlie Aspinwall and Daley Pearson (Doodles, #7DaysLater), producer Sam Moor (CBeebies), and supervising director Richard Jeffery (Tinga Tinga Tales). The series will be executive produced by Libbie Doherty, Acting ABC Head of Children’s Television, and Henrietta Hurford-Jones, Director of Children’s Content for BBC Studios. “The first series was a massive effort from our talented and dedicated young team. -

Brisbane Tv Guide Sunday

Brisbane tv guide sunday Continue Back to main site ABC Radio Channels Print-friendly 7 Day Guides ABC ABC Kids / ABC COMEDY ABC ME ABC NEWS Watch Live Explore ABC TV Whether it's a rom-com, an action movie or family classics you're after, find out what's on free-to-air TV tonight.5.12PM – Grand Designs6PM – The Drum7PM – ABC News7.30PM – 7.308.01PM – Hard Quiz8.32PM – The Weekly With Charlie9.01PM – You Can't Ask That9.32PM – Planet America10.04PM – Would I Lie to You?10.35PM – ABC Late News11.07PM – Four Corners11.53PM – Media WatchABC Comedy/Kids5.15PM – Olobob Top5.35PM – Nella the Princess5.57PM – Octonauts6.20PM – Bluey6.40PM – Hey Duggee7.13PM – Catie's Amazing7.31PM – Spicks and Specks8PM – Spicks and Specks8.29PM – Friday Night Dinner8.52PM – Gavin & Stacey9.22PM – A Moody Christmas9.51PM – Upper Middle Bogan10.20PM – The Office10.42PM – The Office11.05PM – The Office11.26PM – 30 Rock11.48PM – CommunityABC Me5.02PM – The Next Step5.25PM – Dragons : Race to the Edge5.48PM – The Strange Chores6.31PM – What It's Like7.01PM – Bear Grylls' Survival School7.30PM – Shaun the Sheep8PM – The Adventures of Puss in Boots8.30PM – Danger Mouse8.47PM – Project Planet9.12PM – Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles9.35PM – Japanizi : Going Going Going9.57PM – rageABC News5PM – ABC News Hour6PM – ABC Evening News7PM – ABC National News8PM – ABC News Tonight8.45PM – The Business9.01PM – The Drum10PM – The World11PM – ABC Nightly News11.30PM – 7.30SBS5.30PM – Letters and Numbers6PM – Mastermind Australia6.30PM – SBS World News7.35PM – Britain's Great -

Freeview Adds Web to Live Streaming & on Demand FV Line-Up

Switch Media is excited to have provided end-to-end development and delivery of the Freeview FV website, now available on all major browsers. The project delivery included frontend web platform development built on React with editing driven by Prismic CMS, provision of flexible content APIs with support for complex business rules, Electronic Program Guide and program metadata using Gracenote services, 3rd party player integration, as well as OzTAM VPM and Adobe analytics integration. Now viewers can watch and plan all free-to-air TV or access on-demand shows using their online browsers. Simple and easy to use, Freeview brings the best Australian television content to you on any device. You can watch your favourite shows on your computer, phone, tablet or certified TV, wherever you are, whenever and however you want. Check it out at freeview.com.au/watch-tv News Release Source: B&T, 18 December 2018, By Vanessa Gregory. Link: Freeview Adds Web To Live Streaming & On-Demand FV Line-Up FREEVIEW ADDS WEB TO LIVE STREAMING & ON- DEMAND FV LINE-UP In a world-first, free-to-air (FTA) industry body Freeview has launched the new FV online television platform, which allows viewers to stream live TV or use it for on-demand content needs. A major milestone for Freeview, FV allows Australian viewers to access live streaming and available broadcast video-on-demand (BVOD) content from FTA networks through one single web platform on their Mac or PC. FV on the web rounds out the suite of Freeview viewing products available in Australia, including Freeview Plus for smart TVs, and the Freeview FV app available at the Apple App Store and Google Play. -

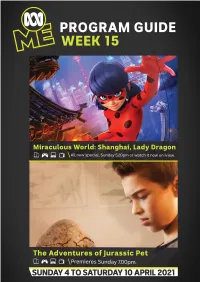

ABC ME Program Guide: Week 15 Index

1 | P a g e ABC ME Program Guide: Week 15 Index Index Sunday, 4 April 2021 ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Monday, 5 April 2021 ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Tuesday, 6 April 2021 .......................................................................................................................................... 11 Wednesday, 7 April 2021 .................................................................................................................................... 15 Thursday, 8 April 2021 ........................................................................................................................................ 19 Friday, 9 April 2021 ............................................................................................................................................. 23 Saturday, 10 April 2021 ....................................................................................................................................... 27 NOTE: Program times may differ in some states if viewing on VAST or Foxtel. More information can be found at ABC Help. 2 | P a g e ABC ME Program Guide: Week 15 Sunday, 4 April 2021 Program Guide Sunday, 4 April 2021 5:30am Voltron: Legendary Defender (Repeat,PG,This program is rated PG, parental guidance is recommended for viewers under fifteen years.) 6:00am -

Regional Free-To-Air Channel Launch & Breakout

REGIONAL FREE-TO-AIR CHANNEL LAUNCH & BREAKOUT Channel Broadcast Launch Channel Breakout Notes 1 January 2004 (Hobart) 30 November 2008 TDT (SD) August 2004 (Launceston) * Renamed from ABC2 on 4 Dec 2017 (reported name change 4 Mar 2018 breakout) 7 March 2005 1 June 2008 * Renamed from ABCKIDS/COMEDY Dec 2020 (reported name change 27 Dec 2020 ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus (SD) June 2008 (RegWA) breakout. Also, ABC changed to ABC TV. 2 July 2009 * Renamed from ONE on 1 Nov 2018 (reported name change 25 Nov 2018 breakout) 27 December 2009 th Bold (SD) 30 July 2009 (Tasmania) * Renamed from Boss to Bold on 10 Dec 2018 August 2011 (RegWA) 12 February 2012 (RegWA) * Renamed from SBS2 on 15 Nov 2016 (reported name change 27 Nov 2016 1 June 2009 28 June 2009 SBS VICELAND (SD) breakout) 9 August 2009 29 November 2009 GO! (SD) 27 December 2009 (NNSW) August 2011 (Reg WA) 12 February 2012 (RegWA) 1 November 2009 (QLD) 27 December 2009 1 December 2009 (Tasmania) 7TWO (SD) 23 December 2009 (NNSW, SNSW, VIC) August 2011 (Reg WA) 12 February 2012 (Reg WA) Copyright © 2021. The Nielsen Company. Confidential Confidential and Proprietary. Company. Nielsen The 2021. © Copyright 4 December 2009 29 November 2009 * Renamed from ABC3 on 19 Sept 2016 (reported name change 2 Oct 2016 breakout) ABC ME (SD) November 2009 (RegWA) 22 July 2010 * Renamed from ABC News 24 on 9 Apr 2017 (reported name change 28 May 2017 1 August 2010 ABC NEWS (HD) August 2010 (RegWA) breakout) 25 September 2010 26 September 2010 7mate (HD) 24 October 2010 (Tasmania) August 2011 (RegWA) 12 February 2012 (RegWA) 26 September 2010 26 September 2010 GEM (HD) August 2011 (RegWA) 12 February 2012 (RegWA) 11 January 2011 9 January 2011 * Renamed from ELEVEN on 1 Nov 2018 (reported name change 25 Nov 2018 Peach (SD) August 2011 (RegWA) 12 February 2012 (RegWA) breakout) June 2010 (RegWA) 12 February 2012 (RegWA) * Channel ceased as at 30 June, 2016 and became WDT. -

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Front Cover: Jeremy Fernandez Reporting from Rosedale, New South Wales

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Front cover: Jeremy Fernandez reporting from Rosedale, New South Wales. Image: David Sciasci Frances Djulibing as Ruby in Operation Buffalo. Image: Ben King / Porchlight Films Letter to the Minister 9 September 2020 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2020. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 9 September 2020 and provides a streamlined, yet full, overview of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC walked beside Australians through the stress, fear and change of late 2019 and early 2020, a time full of uncertainty. It provided constant support for audiences with its wide-ranging and comprehensive news coverage, and help and distraction through quality discussion, entertainment, music, children’s content and specialist services. We adapted to our new operating circumstances expediently, while facing our internal challenges head on. There can be no better example of the ABC’s dedication to Australian stories, culture and experience than its activities throughout 2019-20. I trust you will find the same reflected within this report. Sincerely, -

Today's Television

16 TV MONDAY SEPTEMBER 16 2019 Start the day Zits Insanity Streak with a laugh Who earns a living driving their customers away? Taxi drivers. Where do bees go to the bathroom? At the BP station. Snake Tales Swamp Today’s quiz 1. Retired basketball player Earvin Johnson Jr. is better known by what name? 160919 2. Which musician recorded Cradle of Love and Eyes without a Face? Today’S TeleViSion 3. Justin Trudeau is the current prime minister of nine SeVen abc SbS Ten 6.00 Today. (CC) 6.00 Sunrise. (CC) 6.00 News. 9.00 ABC News 6.00 WorldWatch. 6.30 This Week 6.00 The Talk. (PGa, CC) 7.00 which country? 9.00 Today Extra. (PG, CC) 9.00 The Morning Mornings. 10.00 Antiques With George Stephanopoulos. Ent. Tonight. (R, CC) 7.30 Bold. 11.30 Morning News. (CC) Show. (PG, CC) Roadshow. 11.00 Attenborough (CC) 7.30 WorldWatch. 2.00 (PG, R, CC) 8.00 Celebrity Name 4. Which English city has a 12.00 The Ellen DeGeneres 11.30 Seven Morning And The Empire Of The Ants. Soundtracks: Songs That Defined Game. (PG, R, CC) 8.30 Studio 10. Show. (PG, CC) News. (CC) 12.00 ABC News At Noon. 1.00 History. (Mav, R, CC) (US) 2.50 (PG, CC) 12.00 Dr Phil. (PGl, CC) soccer team known as the Variety show. 12.00 MOVIE: My Father Must Landline. (R, CC) 2.00 Parliament. André Rieu: Forever Vienna. (R, 1.00 Australian Survivor. (PGl, R, Foxes and a rugby union 1.00 Extra.