Winter 2018 Insight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JBI 4.05 Newsletter

FOCUS ON JBI The Newsletter of JBI International • Spring 2007 JBI International JBI Reunites Senior and Volunteer After 40 Years (established in 1931 become a well-respected actor in the Moscow as the Jewish Braille Theater, but never saw her classmate again. Institute) provides the visually impaired, blind, Irina hurried upstairs to her apartment and physically handicapped returned with a photo album with a picture of and reading disabled of their graduating acting class. Sure enough, it was Victor! all backgrounds and ages with free books, Until that presentation, Irina did not realize how magazines and special valuable her acting skills would be for recording publications of Jewish materials for JBI’s Russian Collection . She and general interest in JBI volunteer Victor Persik reunites and reminisces with jumped at the opportunity to “do some acting Audio, Large Print and old friend Irina Gusso. again,” and we arranged for her to visit the JBI Braille. JBI, an Affiliated familiar name from the past touched off a studios. Little did Victor anticipate the Library of the United Amemory, and then a happy reunion, at JBI. wonderful surprise we had arranged for him States Library of It all began last December during a JBI Russian when he arrrived for his recording session. Congress, enables language outreach presentation at a senior There stood Irina, waiting to greet her old individuals with residence in Irvington, New Jersey, where 20 friend with arms wide open! diminished vision to seniors listened as Inna Suholutsky, our Russian understand and Liaison and Outreach Assistant, spoke about JBI JBI offers a wide variety of materials and participate in the cultural Library’s wealth of Russian Talking Books programs for the Russian community world- life of their communities. -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

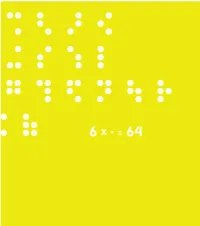

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

1959: Third Conference on Techniques Of

American Foundation ForTheBUND inc. RET 0 RT 5L Hational Braille Cld Service An Organization for the Advancement of Volunteer for Blind People THE THIRD NATIONAL CONFERENCE October 1 959 3 <* • • 3 • • • • 1 l • # # I n Bn j u 3 3 • ® • # • j ^ e « Glut a • • » • c 3 C 3 c 3 j c 3 . - 1 yMV/CL<f OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS OFFICERS President Mi ss Georgie Lee Abel, Ridgewood, N. 1st Vice-President J. Mrs. W. D. Earnest, Jr., R. D. No 1, Butler, N. J, Honorary 2nd Vice-President. Mrs - Alvin H. Kirsner, Des Moines, Iowa Honorary 3rd Vice-President. Mrs. H. J. Brudno, San Mateo, California Corresponding Secretary ....Mrs. Benjamin Friedberger, West Orange, N. Recording J. Secretary Mrs. R. H. Donovan, Brooklyn 38, N. Y. Financial Secretary Mr. Richard Hanna, Madison, N. Treasurer J. Mrs. George Cassidy, East Orange, N. J. Editor of the Bulletin Mrs. George L. Turkeltaub, Great Neck, N. Y. Immediate Past President Miss Josephine L. Taylor, Verona, N. J. DIRECTORS Mr. Robert S. Bray Washington, D. C. Mrs. Sol M. Cohen Florida Mrs. Philip Cohn ..New York Mr. Nelson Coon Massachusetts Mr. Harold Factor Illinois Mrs. Robert Greenwald Texas Miss Marjorie S. Hooper Kentucky Mrs. Dwight A. Johnston Ohio Mrs. Jack Levensky jowa Mr. Guy Marchisio Connecticut Miss Dorothy L. Misbach California Miss Marjorie Postley Pennsylvania COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN Hospitality Mrs. J. L. Maged, Brooklyn, N. Y. Awards Mrs. Emil Drechsler, Newark, N. J Interim Committee on Mathematics....Mrs. A. B. Clark, Fayson Lakes, Butler, N. J. Committee to Study Membership D.^ Mr. Robert S. Bray, Washington,’ C. -

Inspirations from Scientists and Engineers Who Are Blind and Visually Impaired - Lessons to Initiate New Direction for Science Education of Blind Students in Nigeria

Inspirations from Scientists and Engineers Who Are Blind and Visually Impaired - Lessons to Initiate New Direction for Science Education of Blind Students in Nigeria Sariat Adelakun University of Birmingham (United Kingdom) [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Preventing students with visual impairment (SVI) from participating in Science and Mathematics lessons is denying them the opportunity of equal educational opportunity promised by the Federal Government of Nigeria. It is against the Education for all Acts (1990) and No child left behind act (2002) which Nigeria is a signatory. Denying SVI this opportunity put them at a risk of lonely, isolated and unproductive lives (Texas school for the blind and visually impaired). Not only is the possibility of producing future scientist who have impaired vision but the contribution of science in making the blind or visually impaired live a fulfilled life cannot be overstressed. To John Gardener, a blind Physicist it is an awful thing to do to a kid, just wave a course because he cannot learn it. This paper showcase inspirations from scientists who are blind or visually impaired, their contributions in the field and specific techniques used that enabled them to do science are reviewed to serve as direction for Nigeria. For instance, Supalo, a professor of Chemistry employ paid readers to draw responses on all assessment, emphasise the need to develop habit of thinking creatively, know what adaptive technology is available and be good in problem solving skills. Gary Vermeiji said the prevailing attitudes about science and the blind must be reformed. Scientifically inclined blind should not be steered toward the social sciences away from fields in which laboratory and outdoor studies are important. -

Senators Gregory, Anderson, Bieda, Marleau, Johnson, Hood and Ananich Offered the Following Resolution: Senate Resolution No

Senators Gregory, Anderson, Bieda, Marleau, Johnson, Hood and Ananich offered the following resolution: Senate Resolution No. 185. A resolution to proclaim October 16, 2014, as Dr. Abraham Nemeth Day in the state of Michigan. Whereas, Dr. Abraham Nemeth was born on October 16, 1918, in New York City and attended public school as a totally-blind child. He majored in psychology at Brooklyn College and received a master’s degree in psychology from Columbia University; and Whereas, In 1955, Dr. Nemeth joined the faculty of the Department of Mathematics at the University of Detroit Mercy, where he was known for the innovative way he devised to convey mathematical concepts, and served for thirty years until his retirement in 1985; and Whereas, Dr. Nemeth received a Ph.D. in mathematics from Wayne State University in Detroit. He was considered a man of vision and action, with intellectual brilliance and insightful wit; and Whereas, The lack of Braille materials and Dr. Nemeth's determination to pursue his love of math and science led to the creation of what is now known as the Nemeth Braille Code for Mathematics and Science Notation. This was a landmark step in the opportunity for blind students to engage in scientific studies; and Whereas, This unique and revolutionary idea became the official code in the United States, later in Canada and New Zealand, and is recognized as an indispensable tool for instruction in mathematics and science; and Whereas, The Nemeth Code continues to make it possible for blind men and women to pursue careers in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics; supporting themselves and their families and changing the public perception of blindness in a positive way; and Whereas, Dr. -

February 2009: BANA Creates Excellence Award

PRESS RELEASE February 2009 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Judith Dixon, Chairperson Braille Authority of North America PHONE: 1-202-707-0722 E-MAIL: [email protected] BANA Creates Braille Excellence Award In honor of the 200th birthday of Louis Braille, The Braille Authority of North America (BANA) has created the Braille Excellence Award. This award will be given to people or organizations that have developed or contributed to a code, have developed code materials, or software that supports codes, and/or who represent the highest standards of braille production. The first award is being given to Dr. Abraham Nemeth for his contributions making math and science accessible for blind people around the world. Abraham Nemeth was born completely blind in 1918, in New York City, where he spent most of his life. Although mathematics instantly became a passion for Nemeth, he was encouraged by his counselors to pursue a degree in psychology at Brooklyn College. Following his bachelor’s degree, he continued his education at Columbia University, where he earned his master’s in psychology, while attending evening classes in physics and mathematics. As the math courses became increasingly more difficult, Nemeth proceeded to develop his own system of braille mathematics, adopted in the U.S. in 1952, named the Nemeth Braille Code for Mathematics and Science Notation. Shortly after the development of his code, he joined the Department of Mathematics at the University of Detroit, where he created a system of communicating mathematical formulas, called MathSpeak. During this time Nemeth received a Ph.D in mathematics from Wayne State University. -

SR-185, As Adopted by Senate, October 2, 2014 Senators Gregory

SR-185, As Adopted by Senate, October 2, 2014 Senators Gregory, Anderson, Bieda, Marleau, Johnson, Hood and Ananich offered the following resolution: Senate Resolution No. 185. A resolution to proclaim October 16, 2014, as Dr. Abraham Nemeth Day in the state of Michigan. Whereas, Dr. Abraham Nemeth was born on October 16, 1918, in New York City and attended public school as a totally-blind child. He majored in psychology at Brooklyn College and received a master’s degree in psychology from Columbia University; and Whereas, In 1955, Dr. Nemeth joined the faculty of the Department of Mathematics at the University of Detroit Mercy, where he was known for the innovative way he devised to convey mathematical concepts, and served for thirty years until his retirement in 1985; and Whereas, Dr. Nemeth received a Ph.D. in mathematics from Wayne State University in Detroit. He was considered a man of vision and action, with intellectual brilliance and insightful wit; and Whereas, The lack of Braille materials and Dr. Nemeth's determination to pursue his love of math and science led to the creation of what is now known as the Nemeth Braille Code for Mathematics and Science Notation. This was a landmark step in the opportunity for blind students to engage in scientific studies; and Whereas, This unique and revolutionary idea became the official code in the United States, later in Canada and New Zealand, and is recognized as an indispensable tool for instruction in mathematics and science; and Whereas, The Nemeth Code continues to make it possible for blind men and women to pursue careers in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics; supporting themselves and their families and changing the public perception of blindness in a positive way; and Whereas, Dr. -

The Only Thing Worse Than Being Blind Is Having Sight but No Vision. -Helen

BIBHUPRASAD MOHAPATRA RTICLE A The only thing worse than being blind is having sight but no vision. EATURE F -Helen Keller, American author, political activist, and lecturer. Nicholas Saunderson in the chancel of the parish church at Boxworth near Cambridge. Renowned English Scientist, Saunderson possessed the friendship Mathematician and sensible Newtonian of many eminent mathematicians of the was born in the small village of time, such as Sir Isaac Newton, Edmund Thurlstone, Yorkshire, in January 1682 Halley, Abraham De Moivre and Roger ESPITE the fact that they were blind to an exciseman who was a government Cotes. He devised a calculating machine Dphysically, they acquired qualities officer and collected taxes imposed on or abacus, by which he could perform to look at the beauty of the “Queen of goods. He may have been the earliest arithmetical and algebraic operations all Sciences”. Although blind musicians, discoverer of Bayes theorem which was by the sense of touch; this method writers, politicians, and philanthropists named after Thomas Bayes (1701-April 7, is sometimes termed his palpable are most well known, there were some 1761). renowned blind Mathematicians who arithmetic, an account of which is given Unfortunately, when about a year had great vision and also made great in his elaborate Elements of Algebra. old he lost his sight as well as eyes to contributions to Mathematics. Let’s smallpox; but this tragedy did not prevent take a look at some of these great him from acquiring a remarkably good Leonhard Euler mathematicians. education and studying mathematics. He Euler was born on 15 April 1707, in Basel learnt to read by tracing the engravings to Paul Euler and Marguerite Brucker. -

November 2013 Jodi Carlsgaard, Principal Dr

November 2013 Jodi Carlsgaard, Principal Dr. Marjorie Kaiser, Superintendent Upcoming Dates From the Principal’s Desk st Nov. 1 1 Quarter ends Nov. 1-3 Special Olympics State Bowling We have had an outstanding October! Our school Tournament at The Village Bowl, Aberdeen was hustling and bustling at the beginning of the month with homecoming, our students went home Nov 3 Daylight Savings Time ends to spend time with family and friends, parents and nd Nov 4 2 Quarter begins teachers had time to share about student progress, Nov 6 Election Day our students got to show off their artwork, our Nov 11 Veterans Day Program Activities of Daily Living classroom was re-opened 11:30am, Gym and SDSBVI ended the month with some ghoulish fun, costumes, and candy galore! WOW, this is Nov 26 Homegoing just to mention a few things that have gone on this Classes dismiss at 12:10pm month! Lunch served 12:10 – 1:00pm Dorms close at 1:00 PM I had the opportunity to spend some time in Louisville, KY with other Principals of Schools for Nov 28 Happy Thanksgiving the Blind. What an experience! I have learned a Dec 1 Students return great deal about other schools and the best part Dorms open at 1:00pm was I got to share and brag about our school! Dec 2 Classes resume Starting second quarter students will be using IPADS when in class to do research, create projects, read, write, and do calculations. Teachers and students are quite excited to leap into this world of technology. -

Celebrating Mathematicians with Disabilities

CELEBRATING MATHEMATICIANS WITH DISABILITIES ABRAHAM NEMETH JOHN FORBES NASH JR. Abraham was an inventor and mathematician. He studied psychology, and John F. Nash Jr. was an American mathematician who made important earned his undergraduate degree from Brooklyn College and an M.A. from contributions to game theory, differential geometry, and PDEs. He obtained a Columbia University. During his undergrad, he studied mathematics and B.S. and M.S. in mathematics from Carnegie Institute of Technology (now physics, but his academic advisor discouraged him from pursuing Carnegie Mellon University) and a Ph.D. from Princeton University, with a 28- mathematics. After working at agencies for the blind, Abraham decided to page dissertation on noncooperative games. Nash is the only person that has pursue mathematics and obtained a Ph.D. from Wayne State University. been awarded both the Nobel Prize in Economics and the Abel Prize. In advanced courses, he found that there was a need for a braille code that would communicate mathematics in a more effective way. He developed the Nemeth Braille Code for Mathematics and Science Notation, which is still used CARYN LINDA NAVY today. Abraham needed to make use of sighted readers to read mathematics textbook that were otherwise inaccessible; he also needed a method for Navy works on set-theoretic topology. She earned her undergraduate degree dictating his math work for transcription into print. This led to the invention of from MIT, where her undergrad advisor introduced her to topology. She MathSpeak. attended graduate school at University of Wisconsin-Madison and worked as an assistant professor at Bucknell University. -

Literacy Media Decisions Position Paper Released

ASSOCIATION FOR EDUCEDUCATIONION AND REHABILIREHABILITATION OF THE BLINDBLIND AND VISUALVISUALLY IMIMPAIREDIRED AER ReportVol. 30 No. 3 Fall 2013 Literacy Media Decisions Position Paper Released Earlier this year, the AER Board of Directors approved a new position INSIDE THIS ISSUE: paper from the AER Low Vision Rehabilitation Division. Authored by Kelly Lusk, Holly Lawson and Tessa McCarthy with advisory Vanda Pharmaceuticals input from Amanda Lueck, Anne Corn and Barry Kran, “Literacy Media Decisions for Students With Visual Impairments” addresses the becomes major AER sponsor importance of comprehensive evaluations when considering approaches Sequestration hits special to literacy instruction for students who are blind or visually impaired. “For years, Anne Corn and I have felt that the literacy needs of all education students with visual impairments were not well-addressed by current legislation or current practice [in the U.S.],” explained Kelly Lusk, O&M International Conference PhD, CLVT, one of the paper’s co-authors. “The U.S. Individuals with 2013 info Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) specifies individualized education program (IEP) teams must consider braille instruction for students Dr. Abraham Nemeth--In who are visually impaired, which is wonderful. However, the question arises, ‘What happens when braille is not necessarily the best approach Memoriam for a student?’ Current legislation offers little to no guidance for teachers …and much more! and school districts. This position paper addresses that need.” As the authors and contributors of the position paper began working Continued on p. 8 Save money. Get GEICO. Get an additional discount on car insurance as a member of the Association for the Education and Rehabilitation of the Blind and Visually Impaired. -

Brooklyn College Magazine, Fall/Winter 2013, Volume 3 | Number 1

Up Close Film Veteran Jonathan Wacks Leads New Barry R. Feirstein Graduate School of Cinema At the Forefront of Urban Sustainability The Power of Philanthropy to Change Lives B Brooklyn College Magazine Volume 3 | Number 1 | Fall/Winter 2013 11 Holding Destruction at Bay Brooklyn College scientists lead a new institute dedicated to revitalizing Jamaica Bay—one of New York’s greatest natural barriers against superstorms. Brooklyn College Editor-in-Chief Art Director Advisory Committee 2900 Bedford Avenue Keisha-Gaye Anderson Lisa Panazzolo Moraima Cunningham, Director, Student Engagement and Judicial Affairs Brooklyn, NY 11210-2889 Nicole Hosten-Haas, Managing Editor Production Assistant Chief of Staff to the President [email protected] Audrey Peterson Mammen P. Thomas Alex Lang, Assistant Director, Brooklyn College Athletics © 2013 Brooklyn College Steven Schechter, Executive Director of Government and External Affairs Staff Writers Staff Photographers Marla Schreibman ’87, ’89 M.F.A., Director, Alumni Affairs Robert Jones, Jr. ’06, ’08 M.F.A. David Rozenblyum President Jeffrey Sigler ’92, ’95 M.S.,President of the Brooklyn College Alumni Ernesto Mora Craig Stokle Karen L. Gould Association Jamilah Simmons Editorial Assistants Andrew Sillen ’74, Vice President for Institutional Advancement Provost Contributing Writers Taneish Hamilton ’10 Colette Wagner, Assistant Provost for Planning and Special Projects William A. Tramontano Dominique Carson ’12 Mark Zhuravsky ’10 Alex Lang Ikimulisa Livingston Anthony Ramos Jeffrey Sigler ’92, ’95 M.S. 18 Up Close Jonathan Wacks, founding director of the college’s new Barry R. Feirstein Graduate School of Cinema, looks toward cultivating the next generation of film industry leaders. 14 The Other Side of Loss Bernard Garil ’62 and his wife, Ethel, transformed grief into an opportunity for Brooklyn College students to take part in cancer research at some of the nation’s top medical institutions.