HBS Entrepreneurs Oral History Collection Baker Library Special Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semiconductor Industry Social Media Review

Revealed SOCIAL SUCCESS White Paper Who’s winning the social media battle in the semiconductor industry? Issue 2, September 3, 2014 The contents of this White Paper are protected by copyright and must not be reproduced without permission © 2014 Publitek Ltd. All rights reserved Who’s winning the social media battle in the semiconductor industry? Issue 2 SOCIAL SUCCESS Who’s winning the social media battle in the semiconductor industry? Report title OVERVIEW This time, in the interest of We’ve combined quantitative balance, we have decided to and qualitative measures to This report is an update to our include these companies - Intel, reach a ranking for each original white paper from channel. Cross-channel ranking Samsung, Sony, Toshiba, Nvidia led us to the overall index. September 2013. - as well as others, to again analyse the following channels: As before, we took a company’s Last time, we took the top individual “number semiconductor companies 1. Blogs score” (quantitative measure) (according to gross turnover - 2. Facebook for a channel, and multiplied main source: Wikipedia), of this by its “good practice score” 3. Google+ which five were ruled out due (qualitative measure). 4. LinkedIn to the diversity of their offering 5. Twitter The companies were ranked by and the difficulty of segmenting performance in each channel. 6. YouTube activity relating to An average was then taken of semiconductors. ! their positions in each to create the final table. !2 Who’s winning the social media battle in the semiconductor industry? Issue 2 Due to the instantaneous nature of social media, this time we decided to analyse a narrower time frame, and picked a single month - August 2014. -

32 Page Pegasus Layout 090606.Pub

1 Welcome to the Fall 2006 issue of museum for your inspection. The museum give young and old alike the thrill and skill has also acquired through donation a collec- needed to fly Fairchild airplanes. the New Pegasus magazine. It seems only a tion of WWII era airplane gauges, radios and short time since our Premier issue was sent navigation equipment and they are also being The most exciting event to date in pre- out, but summer has come and gone and fall added to the overall display. serving Hagerstown’s aviation heritage hap- is upon us. The spring and summer were pened in the desert of Wyoming at the end of filled with many accomplishments for the A grant from the Washington County August. Donors throughout the community museum, perhaps the greatest of which was Gaming Commission has been received that of Hagerstown and across the country came the completion of several key documents for provides funding for the acquisition of five together to help purchase and thus secure the guiding our future. The board, with the help last of the flying Fairchild C-82 “Flying of several gracious advisors in our commu- Boxcars”. In this issue you will be able to nity, worked diligently on the museum’s ride along with John Seburn and myself in Strategic Plan and Organizational Guide. the article, “Airplane Auction Anxiety-Bid Both of these documents are of vital impor- for the Boxcar”. You can experience the tance to our organization’s overall health and emotional roller coaster ride of the trip as growth and I am pleased to say that the docu- well as those few nail-biting seconds before ments are now completed and are serving as the auction hammer fell and Hagerstown had the guiding outline for our steps forward. -

Timeline of the Semiconductor Industry in South Portland

Timeline of the Semiconductor Industry in South Portland Note: Thank you to Kathy DiPhilippo, Executive Director/Curator of the South Portland Historical Society and Judith Borelli, Governmental Relations of Texas Inc. for providing some of the information for this timeline below. Fairchild Semiconductor 1962 Fairchild Semiconductor (a subsidiary of Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corp.) opened in the former Boland's auto building (present day Back in Motion) at 185 Ocean Street in June of 1962. They were there only temporarily, as the Western Avenue building was still being constructed. 1963 Fairchild Semiconductor moves to Western Avenue in February 1963. 1979 Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corp. is acquired/merged with Schlumberger, Ltd. (New York) for $363 million. 1987 Schlumberger, Ltd. sells its Fairchild Semiconductor Corp. subsidiary to National Semiconductor Corp. for $122 million. 1997 National Semiconductor sells the majority ownership interest in Fairchild Semiconductor to an investment group (made up of Fairchild managers, including Kirk Pond, and Citcorp Venture Capital Ltd.) for $550 million. Added Corporate Campus on Running Hill Road. 1999 In an initial public offering in August 1999, Fairchild Semiconductor International, Inc. becomes a publicly traded corporation on the New York Stock Exchange. 2016 Fairchild Semiconductor International, Inc. is acquired by ON Semiconductor for $2.4 billion. National Semiconductor 1987 National Semiconductor acquires Fairchild Semiconductor Corp. from Schlumberger, Ltd. for $122 million. 1995 National Semiconductor breaks ground on new 200mm factory in December 1995. 1996 National Semiconductor announces plans for a $600 million expansion of its facilities in South Portland; construction of a new wafer fabrication plant begins. 1997 Plant construction for 200mm factory completed and production starts. -

Doktori (Phd) Értekezés

NEMZETI KÖZSZOLGÁLATI EGYETEM Hadtudományi Doktori Iskola Doktori (PhD) értekezés Kis J. Ervin Budapest, 2017. NEMZETI KÖZSZOLGÁLATI EGYETEM Hadtudományi Doktori Iskola Kis J. Ervin A LÉGVÉDELMI ÉS LÉGIERŐK EVOLÚCIÓJA, HELYE, SZEREPE, AZ ARAB-IZRAELI 1967-ES, 1973-AS és 1982- ES HÁBORÚK SORÁN, VALAMINT AZ IZRAELI LÉGIERŐ HAMÁSZ ÉS A HEZBOLLAH ELLENI HÁBORÚS ALKALMAZÁSÁNAK TAPASZTALATAI Doktori (PhD) értekezés Témavezető: Dr. habil. Jobbágy Zoltán ezredes, (Ph.D.) egyetemi docens Budapest, 2017 2 TARTALOMJEGYZÉK I. BEVEZETÉS ....................................................................................................................... 5 I.1. A kutatási témaválasztás indoklás ..................................................................................... 9 I.2 A kutatási téma feldolgozásának és aktualitásának indoklása ........................................ 9 I.3 A tudományos probléma megfogalmazása ................................................................... 12 I.4 Hipotézisek ..... .................................................................................................................... 14 I.5 Kutatási célok...................................................................................................................... 14 I.6 Alkalmazott kutatási módszerek ...................................................................................... 20 I.7. A témával foglalkozó szakirodalom áttekintése.................................................. .............21 I.8 Az értekezés felépítése ....................................................................................................... -

National Venture Capital Association Venture Capital Oral History Project Funded by Charles W

National Venture Capital Association Venture Capital Oral History Project Funded by Charles W. Newhall III William H. Draper III Interview Conducted and Edited by Mauree Jane Perry October, 2005 All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the National Venture Capital Association. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the National Venture Capital Association. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the National Venture Capital Association, 1655 North Fort Myer Drive, Suite 850, Arlington, Virginia 22209, or faxed to: 703-524-3940. All requests should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. Copyright © 2009 by the National Venture Capital Association www.nvca.org This collection of interviews, Venture Capital Greats, recognizes the contributions of individuals who have followed in the footsteps of early venture capital pioneers such as Andrew Mellon and Laurance Rockefeller, J. H. Whitney and Georges Doriot, and the mid-century associations of Draper, Gaither & Anderson and Davis & Rock — families and firms who financed advanced technologies and built iconic US companies. Each interviewee was asked to reflect on his formative years, his career path, and the subsequent challenges faced as a venture capitalist. Their stories reveal passion and judgment, risk and rewards, and suggest in a variety of ways what the small venture capital industry has contributed to the American economy. As the venture capital industry prepares for a new market reality in the early years of the 21st century, the National Venture Capital Association reports (2008) that venture capital investments represented 2% of US GDP and was responsible for 10.4 million American jobs and 2.3 trillion in sales. -

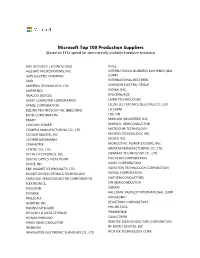

Microsoft Top 100 Production Suppliers (Based on FY14 Spend for Commercially Available Hardware Products)

Microsoft Top 100 Production Suppliers (Based on FY14 spend for commercially available hardware products) AAC ACOUSTIC TECHNOLOGIES INTEL ALLEGRO MICROSYSTEMS, INC. INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES (IBM ALPS ELECTRIC COMPANY CORP.) AMD INTERNATIONAL RECTIFIER AMPEREX TECHNOLOGY, LTD. JOHNSON ELECTRIC GROUP AMPHENOL KIONIX, INC. ANALOG DEVICES KYOCERA/AVX ASKEY COMPUTER CORPORATION LAIRD TECHNOLOGIES ATMEL CORPORATION LELON ELECTRONICS (SUZHOU) CO., LTD BIZLINK TECHNOLOGY INC (BIZCONN) LG CHEM BOYD CORPORATION LITE-ON BRADY MARLOW INDUSTRIES, INC. CHICONY POWER MARVELL SEMICONDUCTOR COMPEQ MANUFACTURING CO., LTD. MICROCHIP TECHNOLOGY COOLER MASTER, INC. MICRON TECHNOLOGY, INC. COOPER BUSSMANN MOLEX, INC. CYMMETRIK MONOLITHIC POWER SYSTEMS, INC. CYNTEC CO., LTD. MURATA MANUFACTURING CO., LTD. DELTA ELECTRONICS, INC. NEWMAX TECHNOLOGY CO., LTD. DIGITAL OPTICS VISTA POINT NICHICON CORPORATION DIODE, INC. NIDEC CORPORATION E&E MAGNETICS PRODUCTS, LTD. NUVOTON TECHNOLOGY CORPORATION ELLINGTON ELECTRONICS TECHNOLOGY NVIDIA CORPORATION FAIRCHILD SEMICONDUCTOR CORPORATION NXP SEMICONDUCTORS FLEXTRONICS ON SEMICONDUCTOR FOXCONN OSRAM FOXLINK PALCONN, PALPILOT INTERNATIONAL CORP. FREESCALE PANASONIC GOERTEK, INC. PEGATRON CORPORATION HANNSTAR BOARD PHILIPS PLDS HITACHI-LG DATA STORAGE PRIMESENSE HONDA PRINTING QUALCOMM HYNIX SEMICONDUCTOR REALTEK SEMICONDUCTOR CORPORATION INFINEON RF MICRO DEVICES, INC. INNOVATOR ELECTRONIC SHENZHEN CO., LTD RICHTEK TECHNOLOGY CORP. ROHM CORPORATION SAMSUNG DISPLAY SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS SAMSUNG SDI SAMSUNG SEMICONDUCTOR SEAGATE SHEN ZHEN JIA AI MOTOR CO., LTD. SHENZHEN HORN AUDIO CO., LTD. SHINKO ELECTRIC INDUSTRIES CO., LTD. STARLITE PRINTER, LTD. STMICROELECTRONICS SUNG WEI SUNUNION ENVIRONMENTAL PACKAGING CO., LTD TDK TE CONNECTIVITY TEXAS INSTRUMENTS TOSHIBA TPK TOUCH SOLUTIONS, INC. UNIMICRON TECHNOLOGY CORP. UNIPLAS (SHANGHAI) CO., LTD. UNISTEEL UNIVERSAL ELECTRONICS INCORPORATED VOLEX WACOM CO., LTD. WELL SHIN TECHNOLOGY WINBOND WOLFSON MICROELECTRONICS, LTD. X-CON ELECTRONICS, LTD. YUE WAH CIRCUITS CO., LTD. -

Fairchild Aviation Corporation, Factory No. 1) MD-137 851 Pennsylvania Avenue Hagerstown Washington County Maryland

KREIDER-REISNER AIRCRAFT COMPANY, FACTORY NO. 1 HAER MD-137 (Fairchild Aviation Corporation, Factory No. 1) MD-137 851 Pennsylvania Avenue Hagerstown Washington County Maryland PHOTOGRAPHS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 ADDENDUM TO: HAER MD-137 KREIDER-REISNER AIRCRAFT COMPANY, FACTORY NO. 1 MD-137 (Fairchild Aviation Corporation, Factory No. 1) 851 Pennsylvania Avenue Hagerstown Washington County Maryland WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD KREIDER-REISNER AIRCRAFT COMPANY, FACTORY NO. 1 (FAIRCHILD AVIATION CORPORATION, FACTORY NO. 1) HAER No. MD-137 LOCATION: 881 Pennsylvania Avenue (Originally 1 Park Lane), Hagerstown, Washington County, Maryland Fairchild Factory No. 1 is located at latitude: 39.654706, longitude: - 77.719042. The coordinate represents the main entrance of the factory, on the north wall at Park Lane. This coordinate was obtained on 22 August, 2007 by plotting its location on the 1:24000 Hagerstown, MD USGS Topographic Quadrangle Map. The accuracy of the coordinate is +/- 12 meters. The coordinate’s datum is North American Datum 1927. The Fairchild Factory No. 1 location has no restriction on its release to the public. DATES OF CONSTRUCTION: 1929, 1931, 1935, 1941, 1965, 1987 BUILDER: Kreider-Reisner Aircraft Company, a subsidiary of Fairchild Aviation Corporation PRESENT OWNER: Vincent Groh PRESENT USE: Light industry, storage SIGNIFICANCE: Kreider-Reisner Factory No. 1 (also known as Fairchild No. 1) was built as a result of a partnership between upstart airplane builders Ammon H. -

2012 High Voltage Design Workshop

2012 HIGH VOLTAGE Electrical Engineering Division DESIGN WORKSHOP Code 560, NASA GSFC Attend On-site or by Webcast DATES: OCT 22-23, 2012 TIME: 7:30 (PDT) AM Start A High Voltage design workshop to be conducted by Steven Battel combining lessons of theoretical and practical design concepts with PLACE: Hameetman Auditorium experience and knowledge from many successful Flight Projects. Cahill Physics and Astronomy BLDG 1216 California Boulevard There is no cost for participation. Registration is necessary to send Located on the campus of participants Webcast and latest workshop information. California Institute of Technology 1200 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, CA 2012 High Voltage Design Workshop: DAY 1 Part 2 GROUNDWORK AND FEEDBACK Lecturer: Steve Battel HIGH POWER KLYSTRON FAST HV MODULATOR Steve Battel is known within the space community for LOW POWER HV MODULATOR his engineering work related to high voltage systems and precision analog electronics used in space science instrumentation. He is a graduate of the RECEPTION (5:30 – 7 PM) University of Michigan and has 35 years experience as an engineer and manager for NASA and DoD projects. He has developed 58 different high DAY 2 voltage designs for space applications with more than 380 units built and 150 CHEMIN HV DESIGN units successfully flown. ALTERNATE CHEMIN HV DESIGN President of Battel Engineering since 1990, Steve has also held engineering MAVEN IUVS HV DESIGN and management positions at the University of Michigan Space Physics USEFUL DESIGN NUGGETS Research Laboratory, Lockheed Palo Alto Research Laboratory, University of ION PUMP HV DESIGN California, Berkeley Space Sciences Laboratory and the University of Arizona BULK HV SUPPLY DESIGN Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. -

Signature Redacted Signature of Author

FAIRMICCO INC. - A CASE STUDY OF AN INDUSTRY/GHETTO COMMUNITY ENTERPRISE IN WASHINGTON, D. C. by RICHARD BORZILLERI B.S.A.E. UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME (1952) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1971 Signature redacted Signature of Author.. Ajfred P. Sloan SyVol of Management, May 1, 1971 Signature redacted Certified by........................................................... Thesis Supervisor Signature redacted Accepted by..........-...... .................. Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Archives 1 *S. INS). rEc JUL 6 1971 1-18RARIES FAIRMICCO INC. - A CASE STUDY OF AN INDUSTRY/GHETTO COMMUNITY ENTERPRISE IN WASHINGTON, D. C. by Richard Borzilleri Submitted to the Alfred P. Sloan School of Management on May 1, 1971, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Management. ABSTRACT This thesis is a case study of Fairmicco Inc., a black capitalism enterprise established to attack the hardcore unemployment problem in Washington, D. C. The sponsors of Fairmicco were the Fairchild Hiller Corporation, the Model Inner City Community Organization (MICCO), a black non-profit confederation of local organizations, and the U. S. Government, which provided initial financing and contracts through its Departments of Commerce, Labor and Defense. Research data for the project were obtained primarily through interviews with various Fairchild Hiller and Fairmicco Inc. personnel, who were deeply involved with the formation and operation of the company. Against the background of the national and local environments existing in 1967, the study describes and analyzes significant events in the company's history from incorporation in February 1968 to present day. -

Discrete Semiconductor Products Fairchild@50

Fairchild Oral History Panel: Discrete Semiconductor Products Fairchild@50 (Panel Session # 3) Participants: Jim Diller Bill Elder Uli Hegel Bill Kirkham Moderated by: George Wells Recorded: October 5, 2007 Mountain View, California CHM Reference number: X4208.2008 © 2007 Computer History Museum Fairchild Semiconductor: Discrete Products George Wells: My name's George Wells. I came to Fairchild in 1969, right in the midst of the Hogan's Heroes, shall we say, subculture, at the time. It was difficult to be in that environment as a bystander, as someone watching a play unfold. It was a difficult time, but we got through that. I came to San Rafael, Wilf asked me to get my ass up to San Rafael and turn it around or shut it down. So I was up in San Rafael for a while, and then I made my way through various different divisions, collecting about 15 of them by the time I was finished. I ended up as executive vice president, working for Wilf, and left the company about a year and a half after the Schlumberger debacle. That's it in a nutshell. Let me just turn over now to Uli Hegel, who was with Fairchild for 38 years, one of the longest serving members, I believe, in the room. Maybe the longest serving member. Uli, why don't you tell us what you did when you came, when you came and what jobs you had when you were there. Uli Hegel: I came to Fairchild in 1959, September 9, and hired into R&D as a forerunner to the preproduction days. -

NJDARM: Collection Guide

NJDARM: Collection Guide - NEW JERSEY STATE ARCHIVES COLLECTION GUIDE Record Group: Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Inc. Series: Aerial Negatives and Prints of New Jersey Sites, 1946-1949, 1951 & 1957 Accession #: 1995.047 Series #: PFAIR001 Guide Date: 2/1997 (JK); rev. 8/2002 (JN) Volume: 7.0 c.f. [14 boxes] Contents | Views List Content Note The founder of Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Sherman Mills Fairchild (1896-1971), was a pioneer in the field of aerial photography. He was the son of a wealthy congressman from New York, George Winthrop Fairchild, whose time- clock and adding-machine business eventually became the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM). In 1916, the younger Fairchild established himself as a technological leader when he developed the first synchronized camera shutter and flash. During World War I, he became interested in aerial photography and, in March 1919, completed a specialized camera for this purpose with a large, between-the-lens shutter. Shortly afterward he established the Fairchild Aerial Camera Corporation with financing from his father. By 1924, he had formed Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Inc., and secured a $7,000 contract to photo-map Newark, New Jersey. This was the first aerial mapping of a major city, but was completed at a cost to the Fairchild company of nearly $30,000. During the next few years, Fairchild's aerial survey company saw greater success mapping areas in Canada, New York City and other eastern cities. Originally purchasing airplanes for the business, Sherman Fairchild eventually began manufacturing his own planes. Unfortunately, little information is available in print with regard to the photo- mapping activities of Fairchild Aerial Surveys during the succeeding decades. -

Fairchild Singapore Story

The Fairchild Singapore Story 1968 - 1987 “Fairchild Singapore Pte Ltd started in 1968. In 1987, it was acquired by National Semiconductor and ceased to exist. The National Semiconductor site at Lower Delta was shutdown and operations were moved to the former Fairchild site at Lorong 3, Toa Payoh. This book is an attempt to weave the hundreds of individual stories from former Fairchild employees into a coherent whole.” 1 IMPORTANT NOTE This is a draft. The final may look significantly different. Your views are welcome on how we can do better. 2 CONTENTS WHAT THIS BOOK IS ABOUT FOREWORD ?? ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION How Fairchild Singapore Came About CHAPTER 1 The Managing Directors CHAPTER 2 Official Opening 1969 CHAPTER 3 1975: Official Opening of Factory Two CHAPTER 4 1977 - 79: Bruce’s Leadership CHAPTER 5 1979: A Schlumberger Company 3 CHAPTER 6 1986: Sold to Fujitsu CHAPTER 7 1987: Sold to National Semiconductor CHAPTER 8 Birth of the Semiconductor Industry in Singapore CHAPTER 9 Aerospace & Defence Division CHAPTER 10 Memory & High Speed Logic Division CHAPTER 11 Digital Integrated Circuit Division CHAPTER 12 Design Centre CHAPTER 13 The Ceramic Division CHAPTER 14 The Quality & Reliability Division CHAPTER 15 The Mil-Aero Division CHAPTER 16 The Standard Ceramic Division CHAPTER 17 The Plastic Leaded Chip Carrier Division 4 CHAPTER 18 Retrenchments CHAPTER 19 The Expats CHAPTER 20 Personnel Department CHAPTER 21 IT Group CHAPTER 22 Life After Fairchild APPENDICES _______________________ ?? INDEX 5 What this Book is About “Fairchild Singapore plant together with other multinational corporations in Singapore have allowed the country to move from Third World to First within one generation” ingapore’s first generation of leaders did what was good for the country.