Canadian Impact Assessment Registry Reference Number 80101 Grassy Mountain Coal Project Crowsnest Pass, AB Following Is My

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highway 3: Transportation Mitigation for Wildlife and Connectivity in the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem

Highway 3: Transportation Mitigation for Wildlife and Connectivity May 2010 Prepared with the: support of: Galvin Family Fund Kayak Foundation HIGHWAY 3: TRANSPORTATION MITIGATION FOR WILDLIFE AND CONNECTIVITY IN THE CROWN OF THE CONTINENT ECOSYSTEM Final Report May 2010 Prepared by: Anthony Clevenger, PhD Western Transportation Institute, Montana State University Clayton Apps, PhD, Aspen Wildlife Research Tracy Lee, MSc, Miistakis Institute, University of Calgary Mike Quinn, PhD, Miistakis Institute, University of Calgary Dale Paton, Graduate Student, University of Calgary Dave Poulton, LLB, LLM, Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative Robert Ament, M Sc, Western Transportation Institute, Montana State University TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables .....................................................................................................................................................iv List of Figures.....................................................................................................................................................v Executive Summary .........................................................................................................................................vi Introduction........................................................................................................................................................1 Background........................................................................................................................................................3 -

Municipal Development Plan

Municipality of Crowsnest Pass MUNICIPAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN BYLAW NO. 1059, 2020 © 2021 Oldman River Regional Services Commission Prepared for the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass This document is protected by Copyright and Trademark and may not be reproduced or modified in any manner, or for any purpose, except by written permission of the Oldman River Regional Services Commission. This document has been prepared for the sole use of the Municipality addressed and the Oldman River Regional Services Commission. This disclaimer is attached to and forms part of the document. ii MUNICIPALITY OF CROWSNEST PASS BYLAW NO. 1059, 2020 MUNICIPAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN BYLAW BEING a bylaw of the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass, in the Province of Alberta, to adopt a new Municipal Development Plan for the municipality. AND WHEREAS section 632 of the Municipal Government Act requires all municipalities in the provinceto adopt a municipaldevelopment plan by bylaw; AND WHEREAS the purpose of the proposed Bylaw No. 1059, 2020 is to provide a comprehensive, long-range land use plan and development framework pursuant to the provisions outlined in the Act; AND WHEREAS the municipal council has requested the preparation of a long-range plan to fulfill the requirementsof the Act and provide for its consideration at a public hearing; NOW THEREFORE, under the authority and subject to the provisions of the Municipal Government Act, Revised Statutes of Alberta 2000, Chapter M-26, as amended, the Council of the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass in the province of Alberta duly assembled does hereby enact the following: 1. Bylaw No. 1059, 2020, being the new Municipal Development Plan Bylaw is hereby adopted. -

AGENDA November 14, 2017 5:30 P.M

DISTRICT OF ELKFORD COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE AGENDA November 14, 2017 5:30 P.M. Council Chambers Elkford's Mission - Through innovative leadership we provide opportunities for responsible growth, in harmony with industry and the environment. We take advantage of opportunities that enhance affordable community living and sustain the quality of life citizens, businesses and visitors expect. Page 1 APPROVAL OF AGENDA (a) Approval of November 14, 2017 Agenda 2 ADOPTION OF MINUTES 3 - 4 (a) Adoption of August 28, 2017 Minutes 3 DELEGATIONS 5 - 134 (a) Draft Community Wildfire Protection Plan • Presenter: Tove Pashkowski, B.A. Blackwell & Associates Ltd. 4 ADJOURNMENT (a) Move to Adjourn Page 1 of 134 Page 2 of 134 DISTRICT OF ELKFORD COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE Minutes August 28, 2017 Present: Mayor McKerracher, Chair Councillor McGregor Councillor Fairbairn Councillor Wildeman Councillor Bertrand Councillor Zarowny Absent: Councillor Robinson Staff Present: Curtis Helgesen, Chief Administrative Officer Scott Beeching, Director, Planning and Development Services Garity Stanley, Director, Leisure Services Duane Allen, Superintendent, Public Works Marilyn Rookes, Director, Financial Services Corey Kortmeyer, Director, Fire Rescue and Emergency Services Curtis Nyuli, Deputy Director, Fire Rescue and Emergency Services Dorothy Szawlowski, Deputy Director, Corporate Services, Recorder There being a quorum of Council, Mayor McKerracher called the meeting to order at 5:37 pm. APPROVAL OF AGENDA (a) Approval of August 28, 2017 Agenda Moved, Seconded AND RESOLVED THAT the agenda for the August 28, 2017 Committee of the Whole Meeting be approved as circulated. CARRIED ADOPTION OF MINUTES (a) Adoption of August 14, 2017 Minutes Moved, Seconded AND RESOLVED THAT the minutes from the August 14, 2017 Committee of the Whole Meeting be adopted as circulated. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

Dinosaur Provincial Park and Area Tourism Development Plan Study

Final Report Dinosaur Provincial Park and Area Tourism Development Plan Study Submitted to: Canadian Badlands Ltd. Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation by IBI Group July 2010 Government of Alberta and Canadian Badlands Ltd. DINOSAUR PROVINCIAL PARK AND AREA TOURISM DEVELOPMENT PLAN STUDY REPORT FINAL REPORT JULY 2010 IBI GROUP FINAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Purpose and Scope of the Study ......................................................................................................... 8 1.2 Study Limitations .................................................................................................................................. 9 1.3 Outline of Report ................................................................................................................................... 9 2. CHARACTERIZATION OF THE STUDY AREA .................................................................... 10 2.1 County of Newell ................................................................................................................................. 13 2.2 City of Brooks ...................................................................................................................................... 16 2.3 Special Area No. 2 .............................................................................................................................. -

R O C K Y M O U N T a I

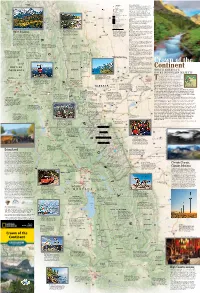

KOOTENAY 115° 114°W Map Key What Is Geotourism All About? NATIONAL According to National Geographic, geotourism “sustains or enhances Community PARK the geographical character of a place—its environment, culture, Museum aesthetics, heritage, and the well-being of its residents.” Geotravelers, To Natural or scenic area then, are people who like that idea, who enjoy authentic sense of Calgary place and care about maintaining it. They find that relaxing and Other point of interest E having fun gets better—provides a richer experience—when they get E Black Diamond Outdoor experience involved in the place and learn about what goes on there. BOB CREEK WILDLAND, AB ALBERTA PARKS Turner Geotravelers soak up local culture, hire local guides, buy local Valley World Heritage site C Radium l foods, protect the environment, and take pride in discovering and EHot Springs os Scenic route ed observing local customs. Travel-spending choices can help or hurt, so i n 22 National Wild and Scenic River geotravelers patronize establishments that care about conservation, BARING CREEK IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK, MT CHUCKHANEY.COM wi nt er Urban area preservation, beautification, and benefits to local people. 543 Learn more at crownofthecontinent.natgeotourism.com. Columbia High River E 23 Protected Areas Wetlands Indian or First Nation reserve Geotraveler Tips: Buy Local 93 541 National forest or reserve High C w Patronize businesses that support the community and its conservation O Frank 40 oo KMt. Joffre N d Longview Lake National park and preservation efforts. Seek out local products, foods, services, and T E 11250 ft I E ELK N 3429 m E Longview Jerky Shop shops. -

IN THIS ISSUE in This Issue Local Poet and Artisan Michael Leeb - Heritage Partner News Investigates Some of Our Earliest Local Stories

Issue #53, December 2018 IN THIS ISSUE In this issue local poet and artisan Michael Leeb - Heritage Partner News investigates some of our earliest local stories. I like to - The List think that I have a grasp on local history, but I had - Feature Articles – The Raven’s always assumed that the battle beneath Crowsnest Nest by Michael Leeb, and Mountain was a myth. Michael’s article cracks open a Coleman Cenotaph by Ian door on this shadowy era of Pass history. Aboriginal McKenzie historians often rely heavily on oral histories and - Book Review – Megan by Iris some of Michael’s work is necessarily speculative. Noble - Sign of the Times Only a few First Nations persons presently reside - News, 100 Years Ago within Crowsnest Pass, and written references to their - Local Heritage Attractions historic presence here are incidental and fragmentary. - Newsletter Archives Articles such as Michael’s will hopefully stimulate interest in further research and documentation of our local indigenous history, challenging as that might be. - Ian McKenzie Thomas Gushul (white shirt) with children Evan and Paraska and unknown friend, early 1920s. Photo: Crowsnest Museum and Archives (6358 Gushul glass negative) Heritage News is a publication of the Crowsnest Heritage Initiative. We are a cooperative committee of local heritage organizations and interested individuals who seek to promote the understanding and appreciation of heritage within the Municipality of Crowsnest Pass, Alberta. For more information on who we are and what we do, click here: http://www.crowsnestheritage.ca/crowsnest-heritage-initiative/ This issue was edited and produced by Ian McKenzie and proofread by Isabel Russell. -

Nicholas Morant Fonds (M300 / S20 / V500)

NICHOLAS MORANT FONDS (M300 / S20 / V500) I.A. PHOTOGRAPHY SERIES : NEGATIVES AND TRANSPARENCIES 1.b. Darkroom files : black and white A-1. Noorduyn aircraft. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 7 photographs : negatives, film, b/w, 6x6 cm. -- Geographic region: Canada. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-1. A-2. High altitude vapor tracks. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 2 photographs : negatives, film, b/w. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- NM note: air tracks. -- Geographic region: Canada. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-2. A-3. Montage air stuff featuring Harvards at Uplands mostly. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 25 photographs : negatives, film, b/w. -- Ottawa airport. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- Geographic region: Ontario. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-3. A-4. R.A.F. Ferry command, Dorval. -- Storage location: missing on acquisition A-5. C.P. Airlines aerial shots. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 6 photographs : negatives, film, b/w. -- Canadian Pacific Airlines. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- NM note: very early shots; first Yukon southern delivery. -- Geographic region: Yukon. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-5. A-6. Pacific coast vigil. -- [ca.1940]. -- 2 photographs : negatives, film, b/w. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- NM note: army on west coast. -- Geographic region: British Columbia. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-6. A-7. Alaskan mountains for montage. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 3 photographs : negatives, film, b/w. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- Geographic region: United States. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-7. A-9. Boeing, Vancouver, on Catalinas. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 8 photographs : negatives, film, b/w. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- Geographic region: British Columbia. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-9. -

Oberti Resort Design Case Study

Oberti Resort Design Case Study by Phil Bamber, Kelly Chow, Jessica Lortie & Tanay Wood 1 OBERTI RESORT DESIGN: A SLIPPERY SLOPE Oberto Oberti, founder of Oberti Resort Design, is in first stages of designing a unique resort concept to add to his record. Oberti is determined to be at the forefront of the next innovative project in British Columbia by developing a new ski hill and resort in North America. The resort will operate during the summer months in order to cater to skiers and snowboarders year round. Oberti’s perplexing vision encompasses a unique mountain experience that will increase Oberti Resort Design’s market share of the ski resort industry. However, the implementation of a new ski resort is tricky due to the large project scope and implementation costs. The timing of opening the ski resort and the location of the resort will be critical to the success of the resort. Now, with financing from Japanese investors, Oberti needs to decide which direction to steer the project in to maximize the success of the new ski resort and adhere to its shareholders. This extraordinary mountain experience plans to attract 180,000 ski visits in the first year of operations, whilst maintaining a stable financial position. OBERTI RESORT DESIGN & PHEDIAS GROUP: BACKGROUND After growing up in Northern Italy within close proximity to the Alps, mountains have been a constant source of inspiration in Oberto Oberti’s life.1 Oberti’s personal mountain endeavours have stimulated curiosity and enriched his design concepts. He first started out as an architect and later established Oberti Resort Design in 2005. -

Glaciers of the Canadian Rockies

Glaciers of North America— GLACIERS OF CANADA GLACIERS OF THE CANADIAN ROCKIES By C. SIMON L. OMMANNEY SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD Edited by RICHARD S. WILLIAMS, Jr., and JANE G. FERRIGNO U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1386–J–1 The Rocky Mountains of Canada include four distinct ranges from the U.S. border to northern British Columbia: Border, Continental, Hart, and Muskwa Ranges. They cover about 170,000 km2, are about 150 km wide, and have an estimated glacierized area of 38,613 km2. Mount Robson, at 3,954 m, is the highest peak. Glaciers range in size from ice fields, with major outlet glaciers, to glacierets. Small mountain-type glaciers in cirques, niches, and ice aprons are scattered throughout the ranges. Ice-cored moraines and rock glaciers are also common CONTENTS Page Abstract ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- J199 Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------- 199 FIGURE 1. Mountain ranges of the southern Rocky Mountains------------ 201 2. Mountain ranges of the northern Rocky Mountains ------------ 202 3. Oblique aerial photograph of Mount Assiniboine, Banff National Park, Rocky Mountains----------------------------- 203 4. Sketch map showing glaciers of the Canadian Rocky Mountains -------------------------------------------- 204 5. Photograph of the Victoria Glacier, Rocky Mountains, Alberta, in August 1973 -------------------------------------- 209 TABLE 1. Named glaciers of the Rocky Mountains cited in the chapter -

Carnivores and Corridors in the Crowsnest Pass

Carnivores and Corridors in the Crowsnest Pass Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 50 Carnivores and Corridors in the Crowsnest Pass Prepared by: Cheryl-Lesley Chetkiewicz and Mark S. Boyce, Principal Investigator Department of Biological Sciences University of Alberta Prepared for: Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Division Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 50 December 2002 Publication No. I/071 ISBN: 0-7785-2182-6 (Printed Edition) ISBN: 0-7785-2183-4 (On-line Edition) ISSN: 1496-7219 (Printed Edition) ISSN: 1496-7146 (On-line Edition) Illustration by: Brian Huffman For copies of this report, contact: Information Centre- Publications Alberta Environment/ Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920- 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone: (780) 422-2079 OR Information Service Alberta Environment/ Alberta Sustainable Resource Development #100, 3115- 12 Street NE Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2E 7J2 Telephone: (403) 297- 3362 OR Visit our web site at: http://www3.gov.ab.ca/srd/fw/riskspecies/ This publication may be cited as: Chetkiewicz, C. 2002. Carnivores and corridors in the Crowsnest Pass. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Fish and Wildlife Division, Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 50. Edmonton, AB. DISCLAIMER The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies or positions of the Department or of the Alberta Government. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Habitat loss, fragmentation and subsequent isolation of habitat patches due to human activities are major factors contributing to species endangerment. Large carnivores such as grizzly bears and cougars are particularly susceptible to fragmentation because they are wide-ranging and exist at relatively low population densities. -

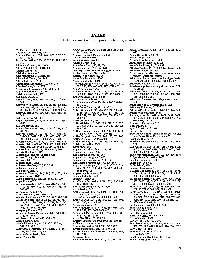

The Letters F and T Refer to Figures Or Tables Respectively

INDEX The letters f and t refer to figures or tables respectively "A" Marker, 312f, 313f Amherstberg Formation, 664f, 728f, 733,736f, Ashville Formation, 368f, 397, 400f, 412, 416, Abitibi River, 680,683, 706 741f, 765, 796 685 Acadian Orogeny, 686, 725, 727, 727f, 728, Amica-Bear Rock Formation, 544 Asiak Thrust Belt, 60, 82f 767, 771, 807 Amisk lowlands, 604 Askin Group, 259f Active Formation, 128f, 132f, 133, 139, 140f, ammolite see aragonite Assiniboia valley system, 393 145 Amsden Group, 244 Assiniboine Member, 412, 418 Adam Creek, Ont., 693,705f Amundsen Basin, 60, 69, 70f Assiniboine River, 44, 609, 637 Adam Till, 690f, 691, 6911,693 Amundsen Gulf, 476, 477, 478 Athabasca, Alta., 17,18,20f, 387,442,551,552 Adanac Mines, 339 ancestral North America miogeocline, 259f Athabasca Basin, 70f, 494 Adel Mountains, 415 Ancient Innuitian Margin, 51 Athabasca mobile zone see Athabasca Adel Mountains Volcanics, 455 Ancient Wall Complex, 184 polymetamorphic terrane Adirondack Dome, 714, 765 Anderdon Formation, 736f Athabasca oil sands see also oil and gas fields, Adirondack Inlier, 711 Anderdon Member, 664f 19, 21, 22, 386, 392, 507, 553, 606, 607 Adirondack Mountains, 719, 729,743 Anderson Basin, 50f, 52f, 359f, 360, 374, 381, Athabasca Plain, 617f Aftonian Interglacial, 773 382, 398, 399, 400, 401, 417, 477f, 478 Athabasca polymetamorphic terrane, 70f, Aguathuna Formation, 735f, 738f, 743 Anderson Member, 765 71-72,73 Aida Formation, 84,104, 614 Anderson Plain, 38, 106, 116, 122, 146, 325, Athabasca River, 15, 20f, 35, 43, 273f, 287f, Aklak