Scottish Birds 33:4 (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habitats and Species Surveys in the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters: Updated October 2016

TOPIC SHEET NUMBER 34 V3 SOUTH RONALDSAY Along the eastern coast of the island at 30m the HABITATS AND SPECIES SURVEYS IN THE PENTLAND videos revealed a seabed of coarse sand and scoured rocky outcrops. The sand was inhabited FIRTH AND ORKNEY WATERS by echinoderms and crustaceans, while the rock was generally bare with sparse Alcyonium digitatum (Dead men’s fi nger) and numerous DUNCANSBY HEAD PAPA WESTRAY WESTRAY Echinus esculentus. Dense brittlestar beds were The seabed recorded to the south of Duncansby SANDAY found to the south. Further north at a depth Head is fl at bedrock with patches of sand, of 50 m the seabed took the form of a mosaic cobbles and boulders. The rock surface is quite ROUSAY MAINLAND STRONSAY of rippled sand, bedrock and boulders with bare other than dense patches of red algae, ORKNEY occasional hydroids and bryozoans. clumps of hydroids and dense brittlestar beds. SCAPA FLOW HOY COPINSAY SOUTH RONALDSAY PENTLAND FIRTH STROMA DUNCANSBY HEAD CAITHNESS VIDEO AND PHOTOGRAPH SITES IN SOUTHERN PART OF ANEMONES URTICINA FELINA ON TIDESWEPT SURVEYED AREA CIRCALITTORAL ROCK Introduction mussels off Copinsay, also found off Noss Head. An extensive coverage of loose-lying Data availability References Marine Scotland Science has been collecting red alga was found in the east of Scapa Flow video and photographic stills from the Pentland The biotope classifi cations and the underlying Moore, C.G. (2009). Preliminary assessment of the on muddy sand and sandeels were also found Firth and Orkney Islands as part of a wider video and images are all available through conservation importance of benthic epifaunal species off west Hoy. -

A Survey of Leach's Petrels on Shetland in 2011

Contents Scottish Birds 32:1 (2012) 2 President’s Foreword K. Shaw PAPERS 3 The status and distribution of the Lesser Whitethroat in Dumfries & Galloway R. Mearns & B. Mearns 13 The selection of tree species by nesting Magpies in Edinburgh H.E.M. Dott 22 A survey of Leach’s Petrels on Shetland in 2011 W.T.S. Miles, R.M. Tallack, P.V. Harvey, P.M. Ellis, R. Riddington, G. Tyler, S.C. Gear, J.D. Okill, J.G Brown & N. Harper SHORT NOTES 30 Guillemot with yellow bare parts on Bass Rock J.F. Lloyd & N. Wiggin 31 Reduced breeding of Gannets on Bass Rock in 2011 J. Hunt & J.B. Nelson 32 Attempted predation of Pink-footed Geese by a Peregrine D. Hawker 32 Sparrowhawk nest predation by Carrion Crow - unique footage recorded from a nest camera M. Thornton, H. & L. Coventry 35 Black-headed Gulls eating Hawthorn berries J. Busby OBITUARIES 36 Dr Raymond Hewson D. Jenkins & A. Watson 37 Jean Murray (Jan) Donnan B. Smith ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS 38 Scottish seabirds - past, present and future S. Wanless & M.P. Harris 46 NEWS AND NOTICES 48 SOC SPOTLIGHT: the Fife Branch K. Dick, I.G. Cumming, P. Taylor & R. Armstrong 51 FIELD NOTE: Long-tailed Tits J. Maxwell 52 International Wader Study Group conference at Strathpeffer, September 2011 B. Kalejta Summers 54 Siskin and Skylark for company D. Watson 56 NOTES AND COMMENT 57 BOOK REVIEWS 60 RINGERS’ ROUNDUP R. Duncan 66 Twelve Mediterranean Gulls at Buckhaven, Fife on 7 September 2011 - a new Scottish record count J.S. -

Saltcoats/Ardrossan

Bathing water profile: Saltcoats/Ardrossan Bathing water: Saltcoats/Ardrossan EC bathing water ID number: UKS7616049 Location of bathing water: UK/Scotland/North Ayrshire (Map1) Year of designation: 1987 Photograph provided courtesy of North Ayrshire Council Bathing water description Saltcoats/Ardrossan bathing water is a 1 km stretch of sandy beach that lies between the towns of Ardrossan and Saltcoats on the North Ayrshire coast. There are rocky areas at Bath Rocks in the north- west and at the former boating ponds in the south-east. The nearby island of Arran can be seen to the west of the bathing water. The bathing water is also known locally as South Beach. It was designated as a bathing water in 1987. During high and low tides the approximate distance to the water’s edge can vary from 0–390 metres. The sandy beach slopes gently towards the water. For local tide information see: http://easytide.ukho.gov.uk/EasyTide/ Our monitoring point for taking water quality samples is located at the western end of the designated area (Grid Ref NS 23453 41997) as shown on Map 1. Monitoring water quality Please visit our website1 for details of the current EU water quality classification and recent results for this bathing water. During the bathing season (1 June to 15 September), designated bathing waters are monitored by SEPA for faecal indicators (bacteria) and classified according to the levels of these indicators in the water. The European standards used to classify bathing waters arise from recommendations made by the World 1 http://apps.sepa.org.uk/bathingwaters/ Health Organisation and are linked to human health. -

Caithness County Council

Caithness County Council RECORDS’ IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference number: CC Alternative reference number: Title: Caithness County Council Dates of creation: 1720-1975 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 10 bays of shelving Format: Mainly paper RECORDS’ CONTEXT Name of creators: Caithness County Council Administrative history: 1889-1930 County Councils were established under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889. They assumed the powers of the Commissioners of Supply, and of Parochial Boards, excluding those in Burghs, under the Public Health Acts. The County Councils also assumed the powers of the County Road Trusts, and as a consequence were obliged to appoint County Road Boards. Powers of the former Police Committees of the Commissioners were transferred to Standing Joint Committees, composed of County Councillors, Commissioners and the Sheriff of the county. They acted as the police committee of the counties - the executive bodies for the administration of police. The Act thus entrusted to the new County Councils most existing local government functions outwith the burghs except the poor law, education, mental health and licensing. Each county was divided into districts administered by a District Committee of County Councillors. Funded directly by the County Councils, the District Committees were responsible for roads, housing, water supply and public health. Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archive 1 Provision was also made for the creation of Special Districts to be responsible for the provision of services including water supply, drainage, lighting and scavenging. 1930-1975 The Local Government Act (Scotland) 1929 abolished the District Committees and Parish Councils and transferred their powers and duties to the County Councils and District Councils (see CC/6). -

1 Marine Scotland. Draft Sectoral Plan for Offshore Wind

Marine Scotland. Draft Sectoral Plan for Offshore Wind (Dec 2019) Supplementary Advice to SNH Consultation Response (25 March 2020). SNH Assessment of Potential Seascape, Landscape and Visual Impacts and Provision of Design Guidance This document sets out SNH’s Landscape and Visual Impact appraisal of each of the Draft Plan Option (DPO) areas presented in the above consultation and the opportunities for mitigating these, through windfarm siting and design. Due to its size, we are submitting it separately from our main response to the draft Plan. We had hoped to be able to submit this earlier within the consultation period and apologise that this was delayed slightly. Our advice is in three parts: Part 1. Context and Approach taken to Assessment Part 2. DPO Assessment and Design Guidance Part 3. DPO Assessment and Design Guidance: Supporting Maps Should you wish to discuss any of the matters raised in our response we would be pleased to do so. Please contact George Lees at [email protected] / 01738 44417. PART 1. CONTEXT AND APPROACH TAKEN TO ASSESSMENT Background 1. In late spring 2018 SNH were invited to participate as part of a Project Steering group to input to the next Sectoral Plan for Offshore Wind Energy by Marine Scotland. SNH landscape advisors with Marine Energy team colleagues recognised this as a real opportunity to manage on-going, planned change from offshore wind at the strategic and regional level, to safeguard nationally important protected landscapes and distinctive coastal landscape character. It also reflected our ethos of encouraging well designed sustainable development of the right scale in the right place and as very much part of early engagement. -

30297-Nidderdale 2012 Schedule 5:Layout 1

P R O G R A M M E (Time-table will be strictly adhered to where possible) ORDER OF JUDGING: Approx. 08.00 a.m. Breeding Hunters (commencing with Ridden Hunter Class) 09.00 a.m. Sheep Dog Trials 09.00 a.m. Carcass Class 09.00 a.m. Dogs Approx. 09.00 a.m. Riding and Turnout Approx. 09.00 a.m. Coloured Horse/Pony In-hand 09.15 a.m. Young Farmers’ Cattle 09.30 a.m. Dry Stone Walling Ballot 09.30 a.m. Beef Cattle (Local) 09.45 a.m. Sheep Approx. 10.00 a.m. All Other Cattle Judging commences Approx. 10.00 a.m. Children’s Riding Classes Approx. 10.00 a.m. Heavy Weight Agricultural Horses 10.00 a.m. Goats 10.00 a.m. Produce, Home Produce and Crafts (Benching 09.45 a.m.) 10.00 a.m. Flowers, Vegetables and Farm Crops (Benching 09.45 a.m.) 10.00 a.m. Poultry, Pigeons and Rabbits 10.30 a.m. ‘Pateley Pantry’ Stands Approx. 10.45 a.m. Mountain & Moorland 11.00 a.m. Pigs Approx. 11.00 a.m. Ridden Coloured 11.00 a.m. Trade Stands 1.15 p.m. Junior Shepherd/Shepherdess Classes (judged at the sheep pens) Approx. 2.00 p.m. Childrens’ Pet Classes (judged in the cattle rings) 2.00 p.m. Sheep - Supreme Championship MAIN RING ATTRACTIONS: 08.00-12.00 Judging - Horse and Pony classes 12.00-12.35 Inch Perfect Trials Display Team 12.35-12.55 Terrier Racing 12.55-1.30 ATV Manoeuvrability Test 1.30-2.00 Young Farmers Mascot Football 2.00-2.20 Parade of Fox Hounds by West of Yore Hunt & Claro Beagles 2.20-3.00 Inch Perfect Trials Display Team 3.00-3.30 GRAND PARADE AND PRESENTATION OF TROPHIES (Excluding Sheep, Goats, Pigs, Produce and WI) Parade of Tractors celebrating 8 decades of Nidderdale Young Farmers Club 3.30- Show Jumping OTHER ATTRACTIONS: Meltham & Meltham Mills Band playing throughout the day 12.00-12.15 St Cuthbert’s Primary School Band 12.15-1.15 Lofthouse & Middlesmoor Silver Band Forestry Exhibition Heritage Marquee Small Traders/Craft Marquee Pateley Pantry Marquee with Cookery Demonstrations 11.00 a.m. -

Sound of Gigha Proposed Special Protection Area (Pspa) NO

Sound of Gigha Proposed Special Protection Area (pSPA) NO. UK9020318 SPA Site Selection Document: Summary of the scientific case for site selection Document version control Version and Amendments made and author Issued to date and date Version 1 Formal advice submitted to Marine Scotland on Marine draft SPA. Nigel Buxton & Greg Mudge. Scotland 10/07/14 Version 2 Updated to reflect change in site status from draft Marine to proposed and addition of SPA reference Scotland number in preparation for possible formal 30/06/15 consultation. Shona Glen, Tim Walsh & Emma Philip Version 3 Creation of new site selection document. Emma Susie Whiting Philip 17/05/16 Version 4 Document updated to address requirements of Greg revised format agreed by Marine Scotland. Mudge Kate Thompson & Emma Philip 17/06/16 Version 5 Quality assured Emma Greg Mudge Philip 17/6/16 Version 6 Final draft for approval Andrew Emma Philip Bachell 22/06/16 Version 7 Final version for submission to Marine Scotland Marine Scotland, 24/06/16 Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Site summary ........................................................................................................ 2 3. Bird survey information ....................................................................................... 5 4. Assessment against the UK SPA Selection Guidelines .................................... 6 5. Site status and boundary ................................................................................. -

Layout 1 Copy

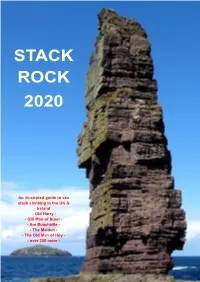

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus Argentatus - Fuscus - Cachinnans) As a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus argentatus - fuscus - cachinnans) as a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations Dorit Liebers-Helbig, Viviane Sternkopf, Andreas J. Helbig{, and Peter de Knijff Abstract Under what circumstances speciation in sexually reproducing animals can occur without geographical disjunction is still controversial. According to the ring species model, a reproductive barrier may arise through “isolation-by-distance” when peripheral populations of a species meet after expanding around some uninhabitable barrier. The classical example for this kind of speciation is the herring gull (Larus argentatus) complex with a circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere. An analysis of mitochondrial DNA variation among 21 gull taxa indicated that members of this complex differentiated largely in allopatry following multiple vicariance and long-distance colonization events, not primarily through “isolation-by-distance”. In a recent approach, we applied nuclear intron sequences and AFLP markers to be compared with the mitochondrial phylogeography. These markers served to reconstruct the overall phylogeny of the genus Larus and to test for the apparent biphyletic origin of two species (argentatus, hyperboreus) as well as the unex- pected position of L. marinus within this complex. All three taxa are members of the herring gull radiation but experienced, to a different degree, extensive mitochon- drial introgression through hybridization. The discrepancies between the mitochon- drial gene tree and the taxon phylogeny based on nuclear markers are illustrated. 1 Introduction Ernst Mayr (1942), based on earlier ideas of Stegmann (1934) and Geyr (1938), proposed that reproductive isolation may evolve in a single species through D. Liebers-Helbig (*) and V. Sternkopf Deutsches Meeresmuseum, Katharinenberg 14-20, 18439 Stralsund, Germany e-mail: [email protected] P. -

November-March 2013 Am Monadh Ruadh Walking Club Programme

November-March 2013 Am Monadh Ruadh Walking Club Programme MEETING POINT: Start time, OS sheet number and grid reference for the meeting point are given for each walk– other map references may be included in the text. PLEASE RING LEADER BEFOREHAND TO CHECK WALK IS TAKING PLACE Some walks are not allocated a specific day to maximise the weather options. Ring the walk leader on the Thursday evening for more information Walks Grading System Our grading system is generally similar to that used by many walking clubs throughout the UK and beyond: A Suitable for fit and experienced hill-walkers. Long mountain days with lots of ascent and descent over rough terrain, some of it steep. A+ indicates a grade at the top end of this category requiring scrambling experience, a good head for heights and the ability to cope with sustained traverses over very rugged and demanding terrain. B Suitable for regular walkers, fit novices or anyone who takes regular aerobic exercise. Mixture of paths, tracks and rough terrain with some steeper gradients in places. B+ indicates a grade at the top end of this category because of longer sections of rough terrain and/or steeper gradients. C Suitable for walkers with average fitness, limited experience, or anyone wanting to walk at an easy pace. Mainly on paths and tracks with easy gradients. C+ indicates a grade at the top end of this category because of some short sections of rougher terrain or steeper gradients (but not both together). Chairman/Walks Co-ordinator: Graham Sage 9 Woodburn Drive Grantown on Spey PH26 3FD Telephone: 01479 870080 E-mail: [email protected] November-March 2013 Am Monadh Ruadh Walking Club Programme Date Meet Leader Walk description Length Ascent Grade 3 Nov Inverdruie Sally GLEN FESHIE Condense cars and drive to 10km/ Sat Long Stay Freshwater forestry commission Car park by Feshiebridge 6ml 01540 CP 651367 NH848046 for 10.15am. -

Identification and Ageing of Glaucous-Winged Gull and Hybrids G

Identification and ageing of Glaucous-winged Gull and hybrids Enno B Ebels, Peter Adriaens & Jon R King laucous-winged Gull Larus glaucescens treated in several (field) guides and identification G breeds around the northern Pacific, from videos published during the last two decades (eg, northern Oregon and Washington, USA, in the Harrison 1983, Grant 1986, Dunn et al 1997, east, via Alaska (including the Aleutian and National Geographic Society 1999, Sibley 2000, Pribilof Islands), USA, to the Komandorskie Doherty & Oddie 2001). This paper discusses the Islands and Kamchatka, north-eastern Russia, in basic aspects of identification of Glaucous-wing- the west. The species winters around the north- ed Gull and various hybrids and illustrates the ern Pacific, from Baja California, Mexico, to different hybrid types and plumages with photo- Hokkaido, Japan (Snow & Perrins 1998). It is a graphs; it does not pretend to be all-inclusive. It rare vagrant in most western states of the USA; it focuses on structure, plumage and bare parts. is very rare inland in central states of the USA, as Differences in voice and/or behaviour (for in- far east as the Great Lakes, and has never been stance, long-call posture) are not treated. The recorded on the American East Coast (cf Sibley paper is based on field studies by Jon King (in 2000). Vagrants have been recorded in Hong Japan and the USA) and Enno Ebels (in Japan), Kong, China, and Hawaii, USA (Snow & Perrins examination by JK of museum skins in various 1998). Amazingly, there are two records of collections, and examination by Peter Adriaens Glaucous-winged Gull in the Western Palearctic: of published and unpublished photographs, a subadult (presumably third-winter) on El including many photographs of spread wings Hierro, Canary Islands, on 7-10 February 1992; from the National Museum of Natural History and an adult at Essaouira, Morocco, on 31 (Washington, DC, USA), the Peabody Museum of January 1995 (Bakker et al 2001 and references Natural History (Yale University, New Haven, therein).