The Conservation and Use of Fossil Vertebrate Sites: British Fossil Reptile Sites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congregational Chapel's Graveyard

https://www.lymeregismuseum.co.uk/research Congregational Chapel Coombe Street, Lyme Regis The Search for a Graveyard Graham Davies, July 2021 The Dinosaurland Fossil Museum in Coombe Street, Lyme Regis, occupies a grade I listed building, a former Congregational (more recently, United Reform) Chapel which closed its doors to religious services in 1985. The Congregational (Independent) Church was formed in Lyme in 1662 following the ejection of the vicar, the Rev A Short, for non-compliance with the Act of Uniformity. He subsequently held services in his own house in Church Street and elsewhere, but was constantly hounded by the authorities. He died in 1697. In 1734 the Rev J Whitty became the new minister and under his guidance a chapel was built in Coombe Street in 1755. Dinosaurland, June 2013 In 2012, research team members, Diane Shaw, Derek Perrey and Graham Davies reviewed the Museum’s Congregational Chapel archives. They found a reference to a ‘curious little graveyard’ on the Lynch, belonging to the Congregational Chapel. In 1841, on behalf of the Chapel, a piece of ground, with two cottages on it (ref 192, 1841 tithe map), situated on the Lynch, was purchased by Mr Theophilus B Goddard from Mr Fowler, of the Hart Inn, at a price of £250. Extensive alterations were made to the cottages, and the part to be used as the burial ground was walled off from the rest. Mr Goddard hoped the Church would repay him his £250 through rents, burial fees and subscriptions. Through lack of subscriptions, Mr Goddard was set free by the Church in 1873 to dispose of the cottages as he saw fit, leaving them the graveyard. -

Jurassic Coast Fossil Acquisition Strategy Consultation Report

Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site Fossil acquisition strategy for the Jurassic Coast- Consultation Document A study to identify ways to safeguard important scientific fossils from the Dorset and East Devon Coast World Heritage Site – prepared by Weightman Associates and Hidden Horizons on behalf of the Jurassic Coast Team, Dorset County Council p Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site Fossil acquisition strategy for the Jurassic Coast CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………………2 2. BACKGROUND…………………………………………………………………………………..2 3. SPECIFIC ISSUES………………………………………..……………………………………….5 4. CONSULTATION WITH STAKEHOLDERS………………………………………………5 5. DISCUSSION……………………………………………………………………………………..11 6. CONCLUSIONS…………………………..……………………………………………………..14 7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………....14 8. APPENDIX..……………………………………………………………………………………...14 1 JURASSIC COAST FOSSIL ACQUISITION STRATEGY 1. Introduction The aim of this project is to identify ways to safeguard important scientific fossils from the Dorset and East Devon Coast World Heritage Site. The identification of placements in accredited museums would enable intellectual access for scientific study and education. Two consulting companies Weightman Associates and Hidden Horizons have been commissioned to undertake this Project. Weightman Associates is a partnership of Gill Weightman and Alan Weightman; they have been in partnership for twenty years working on museum and geology projects. Hidden Horizons Ltd is a museum and heritage consultancy formed in 2013 by Will Watts. When UNESCO granted World Heritage status to the Dorset and East Devon Coast in 2001 it recognised the importance of the Site’s geology and geomorphology. The Jurassic Coast Management Plan 2014-2019 has as one of its aims to “To Conserve and enhance the Site and its setting for science, education and public enjoyment” and the Plan states that a critical success factor is “An increase in the number of scientifically important fossils found along the site that are acquired by or loaned back to local accredited museums”. -

Newsletter for the Friends of Lyme Regis Philpot Museum

MUSEUM FRIEND Newsletter for the Friends of Lyme Regis Philpot Museum January 2018 (Issue 31) Patrons : Sir David Attenborough, Tracy Chevalier, Minnie Churchill Registered Charity No. 278774 CHAIRMAN’S LETTER Dear Friends, Our museum, complete with new Mary Anning Wing, re-opened in July, on time and on budget. A preview, with tea and cake, was enjoyed by the museum volunteers, builders, architects and others involved in the build, all of whom had worked so hard to make this possible. We were bowled over by the new geology gallery and the Fine Foundation Learning Centre; it has been well worth the wait! There have since been two formal openings, the first for all of the local volunteers at which Tracy Chevalier, a Patron of the Friends, gave a gracious speech to the assembled throng in the Marine Theatre. The second was primarily aimed at thanking the HLF and other major granting bodies that donated generously to the Mary Anning Wing. It was great to see Mary Godwin, predecessor to our current Director, and to catch up with Minnie Churchill, another distinguished Patron of the Friends. The star attraction on this occasion was Friends’ Patron, Sir David Attenborough who, in the morning, studied some impressive local fossils with museum geologists Paddy and Chris, followed by a session with local junior school children. In the afternoon, speeches in the Marine Theatre from the Chairman of Trustees and then the Head of HLF for the South West were followed by a typically demonstrative and engaging speech from Sir David on the twin themes of Mary Anning and the importance of Lyme Regis as a birthplace of modern geology. -

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

Notes to Accompany the Malvern U3A Fieldtrip to the Dorset Coast 1-5 October 2018

Notes to accompany the Malvern U3A Fieldtrip to the Dorset Coast 1-5 October 2018 SUMMARY Travel to Lyme Regis; lunch ad hoc; 3:00 pm visit Lyme Regis Museum for Monday 01-Oct Museum tour with Chris Andrew, the Museum education officer and fossil walk guide; Arrive at our Weymouth hotel at approx. 5-5.30 pm Tuesday 02 -Oct No access to beaches in morning due to tides. Several stops on Portland and Fleet which are independent of tides Visit Lulworth Cove and Stair Hole; Poss ible visit to Durdle Door; Lunch at Wednesday 03-Oct Clavell’s Café, Kimmeridge; Visit to Etches Collection, Kimmeridge (with guided tour by Steve Etches). Return to Weymouth hotel. Thur sday 04 -Oct Burton Bradstock; Charmouth ; Bowleaze Cove Beaches are accessible in the morning. Fri day 05 -Oct Drive to Lyme Regis; g uided beach tour by Lyme Regis museum staff; Lunch ad hoc in Lyme Regis; Arrive Ledbury/Malvern in the late afternoon PICK-UP POINTS ( as per letter from Easytravel) Monday 1 Oct. Activity To Do Worcester pick-up Depart Croft Rd at 08.15 Barnards Green pick-up 08.45 Malvern Splash pick-up 08.50 Colwall Stone pick-up 09.10 Pick-ups and travel Ledbury Market House pick-up 09.30 to Lyme Regis Arrive Lyme Regis for Lunch - ad hoc 13.00 – 14.00 Visit Lyme Regis Museum where Chris Andrew from the Museum staff will take us for a tour of 15.00 to 16.30 the Geology Gallery. Depart Lyme Regis for Weymouth 16.30 Check in at Best Western Rembrandt Hotel, 17.30 Weymouth At 6.15pm , we will meet Alan Holiday , our guide for the coming week, in the Garden Lounge of the hotel prior to dinner. -

Weymouth to Portland Railway Walk Uneven Descent to Join the Disused Railway Line Below

This footpath takes you down a steep, Weymouth to Portland Railway Walk uneven descent to join the disused railway line below. This unique landscape As walked on BBC TV’s ‘Railway Walks’ with Julia Bradbury altered by landslips and quarrying is rich in line along dotted fold archaeology and wildlife. Keep a look out This leaflet provides a brief description of the route and main features of for the herd of feral British Primitive goats interest. The whole length is very rich in heritage, geology and wildlife and this View from the Coast Path the Coast from View which have been reintroduced to help is just a flavour of what can be seen on the way. We hope you enjoy the walk control scrub. To avoid the steep path you can continue along the Coast Path at the and that it leads you to explore and find out more. top with excellent views of the weares, railway and Purbeck coast. The 6 mile (approx.) walk can be divided into three sections, each one taking in On reaching the railway line turn right as left will take you very different landscapes and parts of disused railways along the way. to a Portland Port fence with no access. Follow the route along past Durdle Pier, an 18th century stone shipping quay START WEYMOUTH 1 The Rodwell Trail and along the shores of with an old hand winch Derrick Crane. Passing impressive Portland Harbour cliffs you will eventually join the Coast Path down to 2 The Merchants’ railway from Castletown Church Ope Cove where you can return to the main road or to Yeates Incline continue south. -

Lyme Regis 1 Dinosaurland Fossil Museum WC Toilets Marine Aquarium & Long Stay Car Parks 2 Cobb History Exhibition P S P Short Stay Car Parks R 3 Town Mill P I

Lyme Regis 1 Dinosaurland Fossil Museum WC Toilets Marine Aquarium & Long Stay Car Parks 2 Cobb History Exhibition P S P Short Stay Car Parks R 3 Town Mill P I N C G H 4 The Cobb CP Coach Park H E A A D 5 Marine Theatre R R P Town Council Car Parks M O A 6 Guildhall O R D P NCP Car Parks U E A3052 LI ME 7 Lyme Regis Museum T T K I L NE H S N A L Langmoor & Lister Gardens Church N 8 I B KS 3 O M O 1 C AD 9 Jane Austen Garden Footpaths X 65 E M A 10 Lepers Well 0 200 m L IL Golf H 11 Undercliff Nature Reserve Club Produced by PCGraphics (UK) Ltd 2003 C Tourist Information Centre i R H S E U T B R R C M E I L H C Y E River T T Li M m IL H M L LANE E A R M 6 R UPLYME T O NE A O A LA P D U KE G K P NLA G N E E O A T V R R C P S H P 7 D A O R COLWAY T E O CLOSE L N Y B L A E M A P L T LANE I N N E A RI E E L DG E R O Y G A W L R O 5 Y C O F LE 4 L A A HA D I W R H F IE D E H L A N D A W Y O P N E R R A H A R L E R H A W Y CL A T Y K N M U K ' Y IE S O E R L O E V A N A S Y N O E A AD Horn A V E O N V W C B E NE U R A LA Bridg S S CK D S ELIZABETH LE L O A O N TT A O Medical O U E CLOSE PI NE Woodroffe R T S Centre N H A E Cemetery Lyme Regis A V U School OM EN R U Q L Football Club E ERHIL UMM ST GEORGES K S OAD U 3 IN R WC P HILL ST G P L H T AP S Y A E L W M 2 Y R E A CP E R S Y Y E A N D R C SOMERFIELDS N A i E 8 E T O ve A P O R r N 1 Clappentail Park L L L P N A D E im IN 2 St Andrews Meadow N A U G E N RO FERNDOWN E E 3 Springhill Gardens S A 1 R M AV AD D ROAD H D 4 Applebee Way O O RO Fire I A E O V R S 5 Charmouth Close O PO D W IE -

I.—On the Geology of the Neighbourhood of Weymouth and the Adjacent Parts of the Coast of Dorset

Downloaded from http://trn.lyellcollection.org/ at University of Iowa on March 18, 2015 I.—On the Geology of the Neighbourhood of Weymouth and the adjacent Parts of the Coast of Dorset. BY THE REV. W. BUCKLAND, D.D. P.G.S. F.R.S. (PROFESSOR OF GEOLOGY AND MINERALOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD.) AND H. T. DE LA BECHE, ESQ. F.G.S. F.R.S. &c. [Read April 2 and 16, 1830.] 1EW parts of the world present in a small compass so instructive a series of geological phenomena as those which are displayed in the vertical cliffs of the south coast of England. An important portion of this coast, including the Isle of Wight and the Isle of Purbeck, has been well described by Mr. Webster*, and subsequently illustrated by Dr. Fittonf. In the Second Series of the Geological Transactions J, Mr. De la Beche has published sections of the coast from Bridport Harbour to Sidmouth; and in the same volume Dr. Buckland has given drawings of the cliffs from Sidmouth to Beer Head, and from Lyme Regis to the Isle of Portland §. The geological history of the neighbourhood of Weymouth has been partially illustrated by Prof. Sedgwick in the Annals of Philosophy ||; and it will be the object of this paper to supply its full details, illustrated by a map and sections; beginning our observations at the point where Mr. Webster's sections end, viz., at the Pro montory of White Nore, about eight miles E.N.E. of the town of Weymouth, and continuing them to Weymouth and Portland, and thence westward along the Chesil Bank to the cliffs west of Lyme Regis. -

Itinerary #6 - Weymouth Crown Copyright

Itinerary #6 - Weymouth Crown copyright 11 13 12 14 9 10 8 7 2 1 4 3 5 6 Weymouth (popn. 2011, means everything is within walking Weymouth 52,323) is situated on a peninsula, distance of the centre. The shop- sheltered from the north by the ping precinct is partially pedes- 1. Weymouth 180 Ridgeway, from the west by Chesil trianised, while the towns offers a 2. Weymouth Harbour 183 Beach and,f rom the south, by huge range of hotels, guest houses, Esplanade 182 Portland. The estuary of the River restaurants, pubs, traditional fish George III Statue 182 Wey, already a port during the Iron and chips and many small shops Jubilee Clock 182 Age, was developed by the Romans selling traditional seaside wares. Shopping Precinct 183 as a military and commercial deep Pleasure Pier 184 water harbour. Later it became a Royal Navy developments great- South Pier 184 major commercial port, trading ly affected Weymouth from the Sand Sculptures 182 with Europe and North America. 1860s, with the construction of Tudor House 183 Some of the earliest emigrants left the Nothe Fort. The Whitehead 3. The Nothe Fort 188 from here in the 1620s. Torpedo Works were established 4. Melcombe Regis 180 in Wyke Regis 1891, immedi- 5. Wyke Regis 184 Seaside Resorts were becoming ately creating a demand for skilled Rodwell Trail 184 very popular with the rich by the labour. During WWII it em- Sandsfoot Castle 184 late 1700s. Weymouth, with its ployed about 1,600 people, produ- 6. Ferry Bridge 184 long sheltered sandy beach, mild cing up to 20 torpedoes per week. -

Your Free Independent Guide to Lyme Regis

your free independent guide to Lyme Regis @JURASSICMAGS jurassiccoastmagazine.co.uk It’s been a long journey. Excitement builds as you see Lyme in the distance. Take a heading of 284° and follow the leading light into the harbour. The light turns from red to white, you know you’re home. It’s time for a pint. Loaded with 6 different hops including Mosaic and Citra, 284° makes for a refreshing welcome to Lyme Regis. HOPPY LANDINGS WELCOME TO jurassiccoastmagazine.co.uk Evolution Since we set sail in 2014 with our pilot edition of Lyme Magazine, we have noticed one very common theme in our content. Evolution. Lyme Regis is a town which boasts centuries of history, and is situated on a unique coastline which displays millions of years of adaptation. But even today, over the last 6 years, we have seen great change in our little town. A new sea defence scheme, a wonderful new museum, some fantastic new eateries, an eclectic mix of artisans and world class events... just a few of the many designed in Lyme Regis by wonderful attractions that make Lyme one of the UK’s best coastal destinations. //coastline.agency It is because of these wonderful, ever changing highlights that we can keep bringing you Lyme Magazine. Whilst every care has been taken to ensure that Our aim is simple. Help promote businesses in and around Lyme Regis, and to tell the content of this publication is accurate, Coastline the story of the wonderful folk who call ‘The Pearl of Dorset’ home. We do this Publishing Ltd accepts no liability to any party for loss by providing visitors to The Jurassic Coast with a handbag-sized comprehensive or damage caused by errors or omissions. -

Bathing Water Quality in England and Wales -1991

NRA-Water Quality Series 8 BATHING WATER QUALITY IN ENGLAND AND WALES -1991 Report of the National Rivers Authority June 1992 Water Quality Series No. 8 BATHING m TER QUALITY IN ENGLAND AND SCALES - 1991 Report of the National Rivers Authority -rtfona! Rivers AuthonTv $ emotion Centre [ ^ad Office & N R A ^ no---------------- 1 National Rivers Authority I : Water Quality Series No. 8 June 1992 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 099559 National Rivers Authority Rivers House, Waterside Drive, Aztec West, Almondsbury, Bristol BS12 4UD © National Rivers Authority 1992 A ll rights reserved. No part o f this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or othenuise without the prior written permission of the National Rivers Authority First Edition 1992 ISBN No. I 873160 22 4 Other titles in the water quality series: 1. Discharge consent and compliance polity: a blueprint for the future 2. Toxic blue/green algae 3. Bathing water quality in England and Wales — 1990 4. The quality o f rivers, canals and estuaries in England and Wales 5. Proposals for statutory water quality objectives 6. The influence o f agriculture on the quality o f natural waters in England and Wales 7. Water pollution incidents in England and Wales Price £3 (including postage and packing) Further copies may be obtained on application to National Rivers Authority Rivers House, Waterside Drive Aztec West, Almondsbury Bristol BS12 4UD (Cheques should be made payable to The National Rivers Authority) Front cover photograph — Photographic Design Exeter: Polytechnic South West Typeset, printed and bound by Stanley L. -

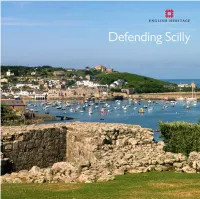

Defending Scilly

Defending Scilly 46992_Text.indd 1 21/1/11 11:56:39 46992_Text.indd 2 21/1/11 11:56:56 Defending Scilly Mark Bowden and Allan Brodie 46992_Text.indd 3 21/1/11 11:57:03 Front cover Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ The incomplete Harry’s Walls of the www.english-heritage.org.uk early 1550s overlook the harbour and English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. St Mary’s Pool. In the distance on the © English Heritage 2011 hilltop is Star Castle with the earliest parts of the Garrison Walls on the Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage.NMR hillside below. [DP085489] Maps on pages 95, 97 and the inside back cover are © Crown Copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019088. Inside front cover First published 2011 Woolpack Battery, the most heavily armed battery of the 1740s, commanded ISBN 978 1 84802 043 6 St Mary’s Sound. Its strategic location led to the installation of a Defence Product code 51530 Electric Light position in front of it in c 1900 and a pillbox was inserted into British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data the tip of the battery during the Second A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. World War. All rights reserved [NMR 26571/007] No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without Frontispiece permission in writing from the publisher.