Odawara Art Foundation Enoura Observatory Opens to the Public from October 9, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’S Daughters – Part 2

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 8. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Abstract This section discusses the complex psychological and philosophical reason for Shogun Yoshimune’s contrasting handlings of his two adopted daughters’ and his favorite son’s weddings. In my thinking, Yoshimune lived up to his philosophical principles by the illogical, puzzling treatment of the three weddings. We can witness the manifestation of his modest and frugal personality inherited from his ancestor Ieyasu, cohabiting with his strong but unconventional sense of obligation and respect for his benefactor Tsunayoshi. Disciplines Family, Life Course, and Society | Inequality and Stratification | Social and Cultural Anthropology This is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 Weddings of Shogun’s Daughters #2- Seigle 1 11Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 e. -

18 Japan Tour Packages

J A P A N 18 Packages / Page 1 of 2 6D 5N Wonderful Central Hokkaido Tour 6D 5N Beautiful East Hokkaido Tour • D1: Arrival in Chitose – Furano • D1: Arrival in Chitose – Tokachigawa (D) • D2: Furano – Biei – Asahikawa (B, L, D) Tokachigawa Onsen Furano Ice Cream Factory, Farm Tomita, Shikisai-no-oka, Shirogane Blue Pond • D2: Tokachigawa – Ikeda – Akan Mashu National Park (B, L, D) • D3: Asahikawa – Otaru (B) Ikeda Wine Castle, Lake Mashu, Lake Kussharo, Onsen in Lake Akan Otokoyama Sake Brewing Museum, Asahiyama Zoo, Asahikawa Ramen Village • D3: Akan Mashu National Park – Abashiri – Shiretoko (B, L, D) • D4: Otaru – Niseko – Lake Toya – Noboribetsu (B, L, D) Abashiri Prison Museum, Mount Tento – view Okhotsk Sea, Okhotsk Otaru Canal, Sakaimachi Street, Otaru Music Box Museum, Kitachi Glass Shop, Ryu-hyo Museum, Shiretoko Goko Lakes (UNESCO) LeTao Confectionery, Niseko Milk Kobo, Niseko Cheese Factory, Lake Toya, • D4: Shiretoko – Kitami – Sounkyo (B, L, D) Noboribetsu Onsen Kitakitsune Farm, Ginga-no-taki and Ryusei-no-taki, Kurodake Ropeway • D5: Noboribetsu – Chitose (B, L) – view Daisetsuzan Mountain Range and Sounkyo Gorge Noboribetsu Jigokudani , Enmado Temple, Noboribetsu Date Jidai Village • D5: Sounkyo – Sapporo (B, L, D) • D6: Departure from Chitose (B) Shiroi Koibito Park (White Lover Chocolate), Odori Park, Sapporo TV Tower, Sapporo Clock Tower, Tanukikoji Shopping Street 6D 5N Delightful South Hokkaido Tour • D6: Sapporo – Departure from Chitose (B) • D1: Arrival in Chitose – Tomakomai • D2: Tomakomai – Noboribetsu (B, D) 6D 5N Extraordinary Shikoku Island Tour Sea Station Plat Seaport Market, Northern Horse Park, Lake • D1: Arrival in Osaka – Naruto – Takamatsu Utonai, Noboribetsu Onsen Naruto Whirlpools, Japanese Sweet-making Experience, Takamatsu Shopping St. -

EARLY MODERN JAPAN 2008 Samurai and the World of Goods

EARLY MODERN JAPAN 2008 Samurai and the World of Goods: vast majority, who were based in urban centers, could ill afford to be indifferent to money and the Diaries of the Toyama Family commerce. Largely divorced from the land and of Hachinohe incumbent upon the lord for their livelihood, usually disbursed in the form of stipends, samu- © Constantine N. Vaporis, University of rai were, willy-nilly, drawn into the commercial Maryland, Baltimore County economy. While the playful (gesaku) literature of the late Tokugawa period tended to portray them as unrefined “country samurai” (inaka samurai, Introduction i.e. samurai from the provincial castle towns) a Samurai are often depicted in popular repre- reading of personal diaries kept by samurai re- sentations as indifferent to—if not disdainful veals that, far from exhibiting a lack of concern of—monetary affairs, leading a life devoted to for monetary affairs, they were keenly price con- the study of the twin ways of scholastic, meaning scious, having no real alternative but to learn the largely Confucian, learning and martial arts. Fu- art of thrift. This was true of Edo-based samurai kuzawa Yukichi, reminiscing about his younger as well, despite the fact that unlike their cohorts days, would have us believe that they “were in the domain they were largely spared the ashamed of being seen handling money.” He forced paybacks, infamously dubbed “loans to maintained that “it was customary for samurai to the lord” (onkariage), that most domain govern- wrap their faces with hand-towels and go out ments resorted to by the beginning of the eight- after dark whenever they had an errand to do” in eenth century.3 order to avoid being seen engaging in commerce. -

1. Outlines and Characteristics of the Great East Japan Earthquake

The Great East Japan Earthquake Report on the Damage to the Cultural Heritage A ship washed up on the rooft op of an building by Tsunami (Oduchi Town, Iwate Prefecture ) i Collapsed buildings (Kesennuma City, Miyagi Prefecture ) ii Introduction The Tohoku Earthquake (East Japan Great Earthquake) which occurred on 11th March 2011 was a tremendous earthquake measuring magnitude 9.0. The tsunami caused by this earthquake was 8-9m high, which subsequently reached an upstream height of up to 40m, causing vast and heavy damage over a 500km span of the pacifi c east coast of Japan (the immediate footage of the power of such forces now being widely known throughout the world). The total damage and casualties due to the earthquake and subsequent tsunami are estimated to be approximately 19,500 dead and missing persons; in terms of buildings, 115,000 totally destroyed, 162,000 half destroyed, and 559,000 buildings being parti ally destroyed. Immediately aft er the earthquake, starti ng with President Gustavo Araoz’s message enti tled ‘ICO- MOS expresses its solidarity with Japan’, we received warm messages of support and encourage- ment from ICOMOS members throughout the world. On behalf of Japan ICOMOS, I would like to take this opportunity again to express our deepest grati tude and appreciati on to you all. There have been many enquiries from all over the world about the state of damage to cultural heritage in Japan due to the unfolding events. Accordingly, with the cooperati on of the Agency for Cultural Aff airs, Japan ICOMOS issued on 22nd March 2011 a fi rst immediate report regarding the state of Important Cultural Properti es designated by the Government, and sent it to the ICOMOS headquarters, as well as making it public on the Japan ICOMOS website. -

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogunâ•Žs

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Economics Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Abstract In this study I shall discuss the marriage politics of Japan's early ruling families (mainly from the 6th to the 12th centuries) and the adaptation of these practices to new circumstances by the leaders of the following centuries. Marriage politics culminated with the founder of the Edo bakufu, the first shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616). To show how practices continued to change, I shall discuss the weddings given by the fifth shogun sunaT yoshi (1646-1709) and the eighth shogun Yoshimune (1684-1751). The marriages of Tsunayoshi's natural and adopted daughters reveal his motivations for the adoptions and for his choice of the daughters’ husbands. The marriages of Yoshimune's adopted daughters show how his atypical philosophy of rulership resulted in a break with the earlier Tokugawa marriage politics. -

Nihonbashi: Edo's Contested Center Marcia Yonemoto

, East Asian History NUMBERS 17/18· JUNE/DECEMBER 1999 Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University 1 Editor Geremie R. Barme Assistant Editor Helen Lo Editorial Board Mark Elvin (Convenor) John Clark Andrew Fraser Helen Hardacre Colin Jeffcott W. ]. F. Jenner Lo Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Design and Production Helen Lo Business Manager Marion Weeks Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This double issue of East Asian History, 17/18, was printed in FebrualY 2000. Contributions to The Editor, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 26249 3140 Fax +61 26249 5525 email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to Subscriptions, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Whose Strange Stories? P'u Sung-ling (1640-1715), Herbert Giles (1845- 1935), and the Liao-chai chih-yi John Minford and To ng Man 49 Nihonbashi: Edo's Contested Center Marcia Yonemoto 71 Was Toregene Qatun Ogodei's "Sixth Empress"? 1. de Rachewiltz 77 Photography and Portraiture in Nineteenth-Century China Regine Thiriez 103 Sapajou Richard Rigby 131 Overcoming Risk: a Chinese Mining Company during the Nanjing Decade Ti m Wright 169 Garden and Museum: Shadows of Memory at Peking University Vera Schwarcz iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing M.c�J�n, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Talisman-"Passport for wandering souls on the way to Hades," from Henri Dore, Researches into Chinese superstitions (Shanghai: T'usewei Printing Press, 1914-38) NIHONBASHI: EDO'S CONTESTED CENTER � Marcia Yonemoto As the Tokugawa 11&)II regime consolidated its military and political conquest Izushi [Pictorial sources from the Edo period] of Japan around the turn of the seventeenth century, it began the enormous (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1975), vol.4; project of remaking Edo rI p as its capital city. -

The Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2013 Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Persinger, Allan, "Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 748. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/748 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Kimberly M. Blaeser My dissertation is a creative translation from Japanese into English of the poetry of Yosa Buson, an 18th century (1716 – 1783) poet. Buson is considered to be one of the most important of the Edo Era poets and is still influential in modern Japanese literature. By taking account of Japanese culture, identity and aesthetics the dissertation project bridges the gap between American and Japanese poetics, while at the same time revealing the complexity of thought in Buson's poetry and bringing the target audience closer to the text of a powerful and mov- ing writer. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48194-6 — Japan's Castles Oleg Benesch , Ran Zwigenberg Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48194-6 — Japan's Castles Oleg Benesch , Ran Zwigenberg Index More Information Index 10th Division, 101, 117, 123, 174 Aichi Prefecture, 77, 83, 86, 90, 124, 149, 10th Infantry Brigade, 72 171, 179, 304, 327 10th Infantry Regiment, 101, 108, 323 Aizu, Battle of, 28 11th Infantry Regiment, 173 Aizu-Wakamatsu, 37, 38, 53, 74, 92, 108, 12th Division, 104 161, 163, 167, 268, 270, 276, 277, 12th Infantry Regiment, 71 278, 279, 281, 282, 296, 299, 300, 14th Infantry Regiment, 104, 108, 223 307, 313, 317, 327 15th Division, 125 Aizu-Wakamatsu Castle, 9, 28, 38, 62, 75, 17th Infantry Regiment, 109 77, 81, 277, 282, 286, 290, 311 18th Infantry Regiment, 124, 324 Akamatsu Miyokichi, 64 19th Infantry Regiment, 35 Akasaka Detached Palace, 33, 194, 1st Cavalry Division (US Army), 189, 190 195, 204 1st Infantry Regiment, 110 Akashi Castle, 52, 69, 78 22nd Infantry Regiment, 72, 123 Akechi Mitsuhide, 93 23rd Infantry Regiment, 124 Alnwick Castle, 52 29th Infantry Regiment, 161 Alsace, 58, 309 2nd Division, 35, 117, 324 Amakasu Masahiko, 110 2nd General Army, 2 Amakusa Shirō , 163 33rd Division, 199 Amanuma Shun’ichi, 151 39th Infantry Regiment, 101 American Civil War, 26, 105 3rd Cavalry Regiment, 125 anarchists, 110 3rd Division, 102, 108, 125 Ansei Purge, 56 3rd Infantry Battalion, 101 anti-military feeling, 121, 126, 133 47th Infantry Regiment, 104 Aoba Castle (Sendai), 35, 117, 124, 224 4th Division, 77, 108, 111, 112, 114, 121, Aomori, 30, 34 129, 131, 133–136, 166, 180, 324, Aoyama family, 159 325, 326 Arakawa -

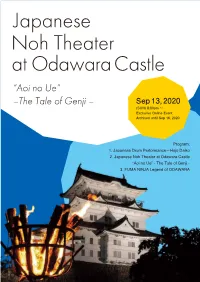

Aoi No Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00Pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived Until Sep 16, 2020

Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived until Sep 16, 2020 Program: 1. Japanese Drum Performance—Hojo Daiko 2. Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” - The Tale of Genji - 3. FUMA NINJA Legend of ODAWARA The Tale of Genji is a classic work of Japanese literature dating back to the 11th century and is considered one of the first novels ever written. It was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a poet, What is Noh? novelist, and lady-in-waiting in the imperial court of Japan. During the Heian period women were discouraged from furthering their education, but Murasaki Shikibu showed great aptitude Noh is a Japanese traditional performing art born in the 14th being raised in her father’s household that had more of a progressive attitude towards the century. Since then, Noh has been performed continuously until education of women. today. It is Japan’s oldest form of theatrical performance still in existence. The word“Noh” is derived from the Japanese word The overall story of The Tale of Genji follows different storylines in the imperial Heian court. for“skill” or“talent”. The Program The themes of love, lust, friendship, loyalty, and family bonds are all examined in the novel. The The use of Noh masks convey human emotions and historical and Highlights basic story follows Genji, who is the son of the emperor and is left out of succession talks for heroes and heroines. Noh plays typically last from 2-3 hours and political reasons. -

EARLY MODERN JAPAN FALL-WINTER, 2004 Patronage

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KnowledgeBank at OSU EARLY MODERN JAPAN FALL-WINTER, 2004 Patronage and the Building Arts in not limited to those who worked in wood, but included thatchers, plasterers, shinglers, and so Tokugawa Japan on. Individuals of lesser ability or status, or ©Lee Butler who were subordinate to the daiku, were shōku University of Michigan 少工, 小工 or “minor craftsmen.” 2 In the warring states era (1467-1568), daiku came to In modern parlance, the term daiku 大工, like refer only to carpenters — those who worked its English counterpart, “carpenter,” refers to one with wood — apparently because of the who builds houses. It is a generic term, fundamental nature of their work, and because suggesting most commonly, however, someone they generally oversaw the whole construction who is involved in the basic construction, as process; their head usually functioned as a opposed to a specialist who is called in to lay the “general contractor.” By the late sixteenth floor, install the roof, or complete a similarly century, the head daiku of a project was narrow task. Neither term, daiku or carpenter, distinguished from his woodworking connotes a level of ability or quality of work; subordinates by the term tōryō 棟梁 (master daiku can be skilled or unskilled. However, builder), or literally the “beams and girders” or both daiku and carpenters deal primarily with “ridgepole” of the group.3 rough work, where tolerances of as much as a The following three-quarters of a century was centimeter can be acceptable and where structural a period of remarkable prosperity for those in the integrity means more than appearance. -

Tokugawa Ieyasu, Shogun

Tokugawa Ieyasu, Shogun 徳川家康 Tokugawa Ieyasu, Shogun Constructed and resided at Hamamatsu Castle for 17 years in order to build up his military prowess into his adulthood. Bronze statue of Tokugawa Ieyasu in his youth 1542 (Tenbun 11) Born in Okazaki, Aichi Prefecture (Until age 1) 1547 (Tenbun 16) Got kidnapped on the way taken to Sunpu as a hostage and sold to Oda Nobuhide. (At age 6) 1549 (Tenbun 18) Hirotada, his father, was assassinated. Taken to Sunpu as a hostage of Imagawa Yoshimoto. (At age 8) 1557 (Koji 3) Marries Lady Tsukiyama and changes his name to Motoyasu. (At age 16) 1559 (Eiroku 2) Returns to Okazaki to pay a visit to the family grave. Nobuyasu, his first son, is born. (At age 18) 1560 (Eiroku 3) Oda Nobunaga defeats Imagawa Yoshimoto in Okehazama. (At age 19) 1563 (Eiroku 6) Engagement of Nobuyasu, Ieyasu’s eldest son, with Tokuhime, the daughter of Nobunaga. Changes his name to Ieyasu. Suppresses rebellious groups of peasants and religious believers who opposed the feudal ruling. (At age 22) 1570 (Genki 1) Moves from Okazaki 天龍村to Hamamatsu and defeats the Asakura clan at the Battle of Anegawa. (At age 29) 152 1571 (Genki 2) Shingen invades Enshu and attacks several castles. (At age 30) 豊根村 川根本町 1572 (Genki 3) Defeated at the Battle of Mikatagahara. (At age 31) 東栄町 152 362 Takeda Shingen’s151 Path to the Totoumi Province Invasion The Raid of the Battlefield Saigagake After the fall of the Imagawa, Totoumi Province 犬居城 武田本隊 (別説) Saigagake Stone Monument 山県昌景隊天竜区 became a battlefield between Ieyasu and Takeda of Yamagata Takeda Main 堀之内の城山Force (another theoried the Kai Province. -

Shaking up Japan: Edo Society and the 1855 Catfish Picture Prints

SHAKING UP JAPAN: EDO SOCIETY AND THE 1855 CATFISH PICTURE PRINTS By Gregory Smits Pennsylvania State University At about 10 pm on the second day of the tenth month of 1855 (November 11 in the solar calendar), an earthquake with a magnitude estimated between 6.9 and 7.1 shook Edo, now known as Tokyo. The earthquake’s shallow focus and its epicenter near the heart of Edo caused more destruction than the magnitude might initially suggest. Estimates of deaths in and around Edo ranged from 7,000 to 10,000. Property damage from the shaking and fires was severe in places, de- stroying at least 14,000 structures. As many as 80 aftershocks per day continued to shake the city until nine days after the initial earthquake. Despite a relatively low 1 in 170 fatality rate, the extensive injuries and property damage, lingering danger of fires, a long and vigorous period of aftershocks, and the locus of the destruction in Japan’s de facto capital city exacerbated the earthquake’s psycho- logical impact.1 Two days after the initial earthquake, hastily printed, anonymous broadsheets and images began to appear for sale around the city. After several weeks had passed, over 400 varieties of earthquake-related prints were on the market, the majority of which featured images of giant catfish, often with anthropomorphic features.2 These metaphoric catfish did not necessarily correspond to an actual species of fish, and I refer to them here by their Japanese name, namazu. The gen- eral name of catfish prints, which included visual elements and text, is namazu-e, with “e” meaning picture.