Global Liquidity Speaker Series Post US Election – Impact of a New Administration January 26, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Committees 2021

Key Committees 2021 Senate Committee on Appropriations Visit: appropriations.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patrick J. Leahy, VT, Chairman Richard C. Shelby, AL, Ranking Member* Patty Murray, WA* Mitch McConnell, KY Dianne Feinstein, CA Susan M. Collins, ME Richard J. Durbin, IL* Lisa Murkowski, AK Jack Reed, RI* Lindsey Graham, SC* Jon Tester, MT Roy Blunt, MO* Jeanne Shaheen, NH* Jerry Moran, KS* Jeff Merkley, OR* John Hoeven, ND Christopher Coons, DE John Boozman, AR Brian Schatz, HI* Shelley Moore Capito, WV* Tammy Baldwin, WI* John Kennedy, LA* Christopher Murphy, CT* Cindy Hyde-Smith, MS* Joe Manchin, WV* Mike Braun, IN Chris Van Hollen, MD Bill Hagerty, TN Martin Heinrich, NM Marco Rubio, FL* * Indicates member of Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee, which funds IMLS - Final committee membership rosters may still be being set “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Visit: help.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Patty Murray, WA, Chairman Richard Burr, NC, Ranking Member Bernie Sanders, VT Rand Paul, KY Robert P. Casey, Jr PA Susan Collins, ME Tammy Baldwin, WI Bill Cassidy, M.D. LA Christopher Murphy, CT Lisa Murkowski, AK Tim Kaine, VA Mike Braun, IN Margaret Wood Hassan, NH Roger Marshall, KS Tina Smith, MN Tim Scott, SC Jacky Rosen, NV Mitt Romney, UT Ben Ray Lujan, NM Tommy Tuberville, AL John Hickenlooper, CO Jerry Moran, KS “Key Committees 2021” - continued: Senate Committee on Finance Visit: finance.senate.gov Majority Members Minority Members Ron Wyden, OR, Chairman Mike Crapo, ID, Ranking Member Debbie Stabenow, MI Chuck Grassley, IA Maria Cantwell, WA John Cornyn, TX Robert Menendez, NJ John Thune, SD Thomas R. -

CALENDAR of BUSINESS Wednesday, January 6, 2021

SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS CONVENED JANUARY 3, 2021 FIRST SESSION ! " DAYS OF SESSION 2 SECOND SESSION ! " CALENDAR OF BUSINESS Wednesday, January 6, 2021 SENATE CONVENES AT 12:30 P.M. PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF JULIE E. ADAMS, SECRETARY OF THE SENATE By JOHN J. MERLINO, LEGISLATIVE CLERK www.SenateCalendar.gov 19–015 2 UNANIMOUS CONSENT AGREEMENTS 3 SSS2021 SSS JANUARY JULY Sun M Tu W Th F Sat Sun M Tu W Th F Sat 1 2 1 2 3 3 4 5 —–6 7 8 9 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 31 FEBRUARY AUGUST 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 28 29 30 31 MARCH SEPTEMBER 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 28 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 APRIL OCTOBER 1 2 3 1 2 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 25 26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 MAY NOVEMBER 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 28 29 30 30 31 JUNE DECEMBER 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 27 28 29 30 26 27 28 29 30 31 JANUARY Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Days Senate met during First Session, One Hundred Seventeenth Congress, are marked (—–). -

Using Activists' Pairwise Comparisons to Measure Ideology

Is John McCain more conservative than Rand Paul? Using activists' pairwise comparisons to measure ideology ∗ Daniel J. Hopkins Associate Professor University of Pennsylvania [email protected] Hans Noely Associate Professor Georgetown University [email protected] April 3, 2017 Abstract Political scientists use sophisticated measures to extract the ideology of members of Congress, notably the widely used nominate scores. These measures have known limitations, including possibly obscuring ideological positions that are not captured by roll call votes on the limited agenda presented to legislators. Meanwhile scholars often treat the ideology that is measured by these scores as known or at least knowable by voters and other political actors. It is possible that (a) nominate fails to capture something important in ideological variation or (b) that even if it does measure ideology, sophisticated voters only observe something else. We bring an alternative source of data to this subject, asking samples of highly involved activists to compare pairs of senators to one another or to compare a senator to themselves. From these pairwise comparisons, we can aggregate to a measure of ideology that is comparable to nominate. We can also evaluate the apparent ideological knowledge of our respondents. We find significant differences between nominate scores and the perceived ideology of politically sophisticated activists. ∗DRAFT: PLEASE CONSULT THE AUTHORS BEFORE CITING. Prepared for presentation at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association in Chicago, April 6-9, 2017. We would like to thank Michele Swers, Jonathan Ladd, and seminar participants at Texas A&M University and Georgetown University for useful comments on earlier versions of this project. -

Digital Divide

Advancing Racial Equity Through Public Policy July 26, 2021 Senator Susan Collins Senator Mike Rounds United States Senate United States Senate 413 Dirksen Senate Office Building 716 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Senator Maggie Hassan Senator Jeanne Shaheen United States Senate United States Senate 324 Hart Senate Office Building 506 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Senator John Hickenlooper Senator Thom Tillis United States Senate United States Senate 374 Russell Senate Office Building 113 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Senator Angus King Senator Jon Tester United States Senate United States Senate 133 Hart Senate Office Building 311 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Senator Joe Manchin Senator Todd Young United States Senate United States Senate 306 Hart Senate Office Building 185 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Senator Jerry Moran Senator Mark Warner United States Senate United States Senate 521 Dirksen Senate Office Building 703 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Senator Rob Portman United States Senate 448 Russell Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Dear Members of Congress: CEO Action for Racial Equity is a Fellowship of over 100 companies that mobilizes a community of business leaders with diverse expertise across multiple industries and geographies to identify, develop and promote scalable and sustainable public policies and corporate engagement strategies that will address systemic racism, social injustice and improve societal well-being for 47M+ Black Americans. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted how essential broadband is to American life, including education, jobs, and medical care. -

Select and Special Committees of the Senate

SELECT AND SPECIAL COMMITTEES OF THE SENATE Committee on Indian Affairs 838 Hart Senate Office Building 20510–6450 phone 224–2251, http://indian.senate.gov [Created pursuant to S. Res. 4, 95th Congress; amended by S. Res. 71, 103d Congress] meets every Wednesday of each month John Hoeven, of North Dakota, Chair Tom Udall, of New Mexico, Vice Chair John Barrasso, of Wyoming. Maria Cantwell, of Washington. John McCain, of Arizona. Jon Tester, of Montana. Lisa Murkowski, of Alaska. Brian Schatz, of Hawaii. James Lankford, of Oklahoma. Heidi Heitkamp, of North Dakota. Steve Daines, of Montana. Catherine Cortez Masto, of Nevada. Mike Crapo, of Idaho. Tina Smith, of Minnesota. Jerry Moran, of Kansas. (No Subcommittees) STAFF Majority Staff Director / Chief Counsel.—Mike Andrews. Deputy Chief Counsel.—Rhonda Harjo. Senior Policy Advisor.—Brandon Ashley. Counsel.—Holmes Whelan. Policy Advisors: Jacqueline Bisille, John Simermeyer. Legal Fellow.—Chase Goodnight. Staff Assistant.—Reid Dagul. Minority Staff Director / Chief Counsel.—Jennifer Romero. Senior Counsel.—Ken Rooney. Counsel.—Ray Martin. Senior Policy Advisor.—Anthony Sedillo. Policy Advisor.—Kim Moxley. Administrative Director.—Jim Eismeier. Clerk.—Avis Dubose. Systems Administrator.—Dasan Fish. GPO Detailee.—Jack Fulmer. Legal Fellow.—Connie Tsofie de Harro. Staff Assistant.—Elise Planchet. GPO Detailee.—Josh Bertalotto. 385 386 Congressional Directory Select Committee on Ethics 220 Hart Senate Office Building 20510, phone 224–2981, fax 224–7416 [Created pursuant to S. Res. 338, 88th Congress; amended by S. Res. 110, 95th Congress] Johnny Isakson, of Georgia, Chair Christopher A. Coons, of Delaware, Vice Chair Pat Roberts, of Kansas. Brian Schatz, of Hawaii. James E. Risch, of Idaho. -

GUIDE to the 117Th CONGRESS

GUIDE TO THE 117th CONGRESS Table of Contents Health Professionals Serving in the 117th Congress ................................................................ 2 Congressional Schedule ......................................................................................................... 3 Office of Personnel Management (OPM) 2021 Federal Holidays ............................................. 4 Senate Balance of Power ....................................................................................................... 5 Senate Leadership ................................................................................................................. 6 Senate Committee Leadership ............................................................................................... 7 Senate Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................. 8 House Balance of Power ...................................................................................................... 11 House Committee Leadership .............................................................................................. 12 House Leadership ................................................................................................................ 13 House Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................ 14 Caucus Leadership and Membership .................................................................................... 18 New Members of the 117th -

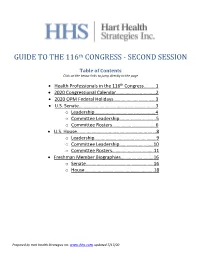

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

Senate Class Card List:92-930 2/3/15 11:47 PM Page 1

92-930; Senate Class Card List:92-930 2/3/15 11:47 PM Page 1 United States Senate S. Pub. 114–2 ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Vice President ORRIN G. HATCH, President Pro Tempore JULIE E. ADAMS, Secretary of the Senate LAURA C. DOVE, Secretary for the Majority FRANK J. LARKIN, Sergeant at Arms GARY B. MYRICK, Secretary for the Minority TERM TERM NAME RESIDENCE NAME RESIDENCE EXPIRES EXPIRES LAMAR ALEXANDER ..................... Maryville, TN ........................... Jan. 3, 2021 Angus S. King, Jr.* .................. Brunswick, ME........................ Jan. 3, 2019 KELLY AYOTTE............................ Nashua, NH............................. Jan. 3, 2017 MARK KIRK................................ Highland Park, IL .................... Jan. 3, 2017 Tammy Baldwin....................... Madison, WI............................ Jan. 3, 2019 Amy Klobuchar ....................... Minneapolis, MN..................... Jan. 3, 2019 JOHN BARRASSO ........................ Casper, WY ............................. Jan. 3, 2019 JAMES LANKFORD1 ..................... Edmond, OK ........................... Jan. 3, 2017 Michael F. Bennet ................... Denver, CO.............................. Jan. 3, 2017 Patrick J. Leahy ...................... Middlesex, VT ......................... Jan. 3, 2017 Richard Blumenthal................. Greenwich, CT ........................ Jan. 3, 2017 MIKE LEE .................................. Alphine, UT ............................. Jan. 3, 2017 ROY BLUNT .............................. -

Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115Th Congress

Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress Senate Committee Assignments for the 115th Congress AGRICULTURE, NUTRITION AND FORESTRY BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Pat Roberts, Kansas Debbie Stabenow, Michigan Mike Crapo, Idaho Sherrod Brown, Ohio Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont Richard Shelby, Alabama Jack Reed, Rhode Island Mitch McConnell, Kentucky Sherrod Brown, Ohio Bob Corker, Tennessee Bob Menendez, New Jersey John Boozman, Arkansas Amy Klobuchar, Minnesota Pat Toomey, Pennsylvania Jon Tester, Montana John Hoeven, North Dakota Michael Bennet, Colorado Dean Heller, Nevada Mark Warner, Virginia Joni Ernst, Iowa Kirsten Gillibrand, New York Tim Scott, South Carolina Elizabeth Warren, Massachusetts Chuck Grassley, Iowa Joe Donnelly, Indiana Ben Sasse, Nebraska Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota John Thune, South Dakota Heidi Heitkamp, North Dakota Tom Cotton, Arkansas Joe Donnelly, Indiana Steve Daines, Montana Bob Casey, Pennsylvania Mike Rounds, South Dakota Brian Schatz, Hawaii David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland David Perdue, Georgia Chris Van Hollen, Maryland Luther Strange, Alabama Thom Tillis, North Carolina Catherine Cortez Masto, Nevada APPROPRIATIONS John Kennedy, Louisiana REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC BUDGET Thad Cochran, Mississippi Patrick Leahy, Vermont REPUBLICAN DEMOCRATIC Mitch McConnell, Patty Murray, Kentucky Washington Mike Enzi, Wyoming Bernie Sanders, Vermont Richard Shelby, Dianne Feinstein, Alabama California Chuck Grassley, Iowa Patty Murray, -

Senate Confirms Alex Azar As New Hhs Secretary Despite Democrats’ Opposition

SENATE CONFIRMS ALEX AZAR AS NEW HHS SECRETARY DESPITE DEMOCRATS’ OPPOSITION Senate Republicans and six Democrats voted in favor HHS secretary because Azar shares his goal “of on confirming President Donald Trump’s nominee to transforming our current health care system, which can be HHS Secretary, Alex Azar, approving his nomination often lead to mistreatment and overuse, to one that 55-43. Azar’s confirmation ends Acting HHS Secretary rewards health care providers based on the quality of Eric Hargan’s time at the department following former care patients receive.” Carper added that he intends Secretary Tom Price’s resignation after a private plane to monitor Azar’s actions to ensure he follows through scandal. on his promises. Six Democrats and one Independent voted in favor During nomination hearings held by the of Azar’s nomination, including Sens. Tom Carper Senate Finance Committee and Senate Health (D-DE), Chris Coons (D-DE), Joe Donnelly (D-IN), Heidi Committee, Democrats criticized Azar’s history as a Heitkamp (D-ND), Doug Jones (D-AL), Joe Manchin (D- pharmaceutical executive for Eli Lilly USA, saying he WV) and Angus King (I-ME). Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) was significantly raised prices during his tenure. Democrats the only Republican to vote against Azar’s nomination. also criticized his views on the Affordable Care Act Both Sens. Bob Corker (R-TN) and John McCain (R-AZ) and were skeptical that he would work to uphold the did not vote. law. Although the majority of Democrats stood against Health care advocates and stakeholders had mixed Azar, Carper said that he voted in favor of Trump’s reactions to Azar’s confirmation.n . -

Congressional Directory WEST VIRGINIA

290 Congressional Directory WEST VIRGINIA WEST VIRGINIA (Population 2010, 1,852,994) SENATORS JOE MANCHIN III, Democrat, of Fairmont, WV; born in Farmington, August 24, 1947; edu- cation: graduated, Farmington High School, Farmington, 1965; B.A., West Virginia University, WV, 1970; businessman; member of the West Virginia House of Delegates, 1982–86; member of the West Virginia State Senate, 1986–96; Secretary of State, West Virginia, 2000–04; elected governor of West Virginia in 2004 and reelected in 2008; chairman of the National Governors Association, 2010; religion: Catholic; married: Gayle Conelly; three children, Heather, Joseph IV, and Brooke; seven grandchildren; committees: Armed Services; Commerce, Science, and Transportation; Energy and Natural Resources; Veterans’ Affairs; elected to the 111th U.S. Sen- ate in the November 2, 2010, special election to the term ending January 3, 2013, a seat pre- viously held by Senator Carte Goodwin, and took the oath of office on November 15, 2010. Office Listings http://manchin.senate.gov https://www.facebook.com/joemanchinIII https://twitter.com/sen–joemanchin 306 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 ....................................................... (202) 224–3954 Chief of Staff.—Hayden Rogers. FAX: 228–0002 Legislative Director.—Kirtan Mehta. Communications Director.—Jonathan Kott. 900 Pennsylvania Avenue, Suite 629, Charleston, WV 25302 ................................................. (304) 342–5855 State Director.—Mara Boggs. 261 Aikens Center, Suite 305, Martinsburg, -

April 30, 2021 the Honorable Jeanne Shaheen Chair Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies 506 Hart Se

April 30, 2021 The Honorable Jeanne Shaheen The Honorable Jerry Moran Chair Ranking Member Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Science, and Related Agencies 506 Hart Senate Office Building 521 Dirksen Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 Dear Chair Shaheen and Ranking Member Moran, As you begin work preparing the Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, we urge you to include robust funding for the Economic Development Administration (EDA) and its vital grant programs. Since 1965, EDA has helped local and regional stakeholders address the economic and infrastructure needs of communities across the country, focusing on private-sector job creation and economic growth in distressed areas. With a modest budget, EDA programs have developed a record of making strategic investments and building community and regional partnerships to expand business in areas such as advanced manufacturing, science, health care, and technology. Between FY12 and FY19, EDA has invested over $2.283 billion in 5,471 projects to help build the capacity for locally-driven economic development projects. These projects are expected to create and/or retain 335,620 jobs and attract over $47.1 billion in private investment. Many communities, especially those in rural areas, have benefited from EDA grants to support the job skills training, technical assistance, and infrastructure improvements needed to attract new businesses and ensure existing businesses have the opportunity to adapt to changing market circumstances. EDA has invested nearly 60 percent of its funds in rural areas since FY12, which has leveraged over $13.7 billion in private investment in these communities.