Issues in Locating Hindus' Sacred Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

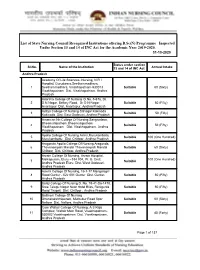

Programme Inspected Under Section 13 and 14 of INC Act for the Academic Year 2019-2020

List of State Nursing Council Recognised Institutions offering B.Sc(N) Programme Inspected Under Section 13 and 14 of INC Act for the Academic Year 2019-2020. 31-10-2020 Status under section Sl.No. Name of the Institution 13 and 14 of INC Act Annual Intake Andhra Pradesh Academy Of Life Sciences- Nursing, N R I Hospital, Gurudwara,Seethammadhara, 1 Seethammadhara, Visakhapatnam-530013 Suitable 60 (Sixty) Visakhapatnam Dist. Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh Adarsha College Of Nursing D.No. 5-67a, Dr. 2 D.N.Nagar, Bellary Road, Dr D N Nagar Suitable 50 (Fifty) Anantapur Dist. Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh Aditya College Of Nursing Srinagar Kakinada 3 Suitable 50 (Fifty) Kakinada Dist. East Godavari, Andhra Pradesh American Nri College Of Nursing Sangivalasa, Bheemunipatnam Bheemunipatnam 4 Suitable 50 (Fifty) Visakhapatnam Dist. Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh Apollo College Of Nursing Aimsr,Murukambattu 5 Suitable 100 (One Hundred) Murukambattu Dist. Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh Aragonda Apollo College Of Nursing Aragonda, 6 Thavanampalli Mandal Thavanampalli Mandal Suitable 60 (Sixty) Chittoor Dist. Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh Asram College Of Nursing, Asram Hospital, Malkapuram, Eluru - 534 004, W. G. Distt. 100 (One Hundred) 7 Suitable Andhra Pradesh Eluru Dist. West Godavari, Andhra Pradesh Aswini College Of Nursing, 15-1-17 Mangalagiri 8 Road Guntur - 522 001 Guntur Dist. Guntur, Suitable 50 (Fifty) Andhra Pradesh Balaji College Of Nursing D. No. 19-41-S6-1478, 9 Sree Telugu Nagar Near Hotel Bliss, Renigunta Suitable 50 (Fifty) Road Tirupati Dist. Chittoor , Andhra Pradesh Bollineni College Of Nursing 10 Dhanalakshmipuram, Muthukur Road Spsr Suitable 60 (Sixty) Nellore Dist. Nellore, Andhra Pradesh Care Waltair College Of Nursing, A S Raja Complex, Waltair Main Road, Visakhapatnam- 11 Suitable 40 (Forty) 530002 Visakhapatnam Dist. -

There Was Need to Focus on a Few Successful Models and Replicate the Success Than Pursue the Creation of a Plethora of New Initiatives

SOCIAL IMPACT ANALYSIS FOR ACTIVITIES IN 2011 HINDU FORUM OF BRITAIN 10 OCTOBER 2013 EPG ECONOMIC AND STRATEGY CONSULTING, 78 PALL MALL, LONDON, SW1Y 5ES Hindu Forum of Britain Social impact analysis Important notice This report has been prepared by EPG Economic and Strategy Consulting ("EPG") for the Hindu Forum of Britain (“HFB”) in connection with a social impact analysis of the HFB's community and charitable activities in 2011 under the terms of the engagement letter between EPG and HFB dated 29 August 2012 (the “Contract”). This report has been prepared solely for the benefit of the HFB in connection with a social impact analysis and no other party is entitled to rely on it for any purpose whatsoever. EPG accepts no liability or duty of care to any person (except to the HFB under the relevant terms of the Contract) for the content of the report. Accordingly, EPG disclaims all responsibility for the consequences of any person (other than the HFB on the above basis) acting or refraining to act in reliance on the report or for any decisions made or not made which are based upon such report. The report contains information obtained or derived from a variety of sources. EPG has not sought to establish the reliability of those sources or verified the information so provided. Accordingly no representation or warranty of any kind (whether express or implied) is given by EPG to any person (except to the HFB under the relevant terms of the Contract) as to the accuracy or completeness of the report. The report is based on information available to EPG at the time of writing of the report and does not take into account any new information which becomes known to us after the date of the report. -

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (As on 20.11.2020)

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (as on 20.11.2020) Sl. Year of State District Block/ Taluka Village/ Habitation Name of the School Status No. sanction 1 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Y. Ramavaram P. Yerragonda EMRS Y Ramavaram 1998-99 Functional 2 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Kodavalur Kodavalur EMRS Kodavalur 2003-04 Functional 3 Andhra Pradesh Prakasam Dornala Dornala EMRS Dornala 2010-11 Functional 4 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Gudem Kotha Veedhi Gudem Kotha Veedhi EMRS GK Veedhi 2010-11 Functional 5 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Buchinaidu Kandriga Kanamanambedu EMRS Kandriga 2014-15 Functional 6 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Maredumilli Maredumilli EMRS Maredumilli 2014-15 Functional 7 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Ozili Ojili EMRS Ozili 2014-15 Functional 8 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Meliaputti Meliaputti EMRS Meliaputti 2014-15 Functional 9 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Bhamini Bhamini EMRS Bhamini 2014-15 Functional 10 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Munchingi Puttu Munchingiputtu EMRS Munchigaput 2014-15 Functional 11 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Dumbriguda Dumbriguda EMRS Dumbriguda 2014-15 Functional 12 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Makkuva Panasabhadra EMRS Anasabhadra 2014-15 Functional 13 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Kurupam Kurupam EMRS Kurupam 2014-15 Functional 14 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Pachipenta Guruvinaidupeta EMRS Kotikapenta 2014-15 Functional 15 Andhra Pradesh West Godavari Buttayagudem Buttayagudem EMRS Buttayagudem 2018-19 Functional 16 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Chintur Kunduru EMRS Chintoor 2018-19 Functional -

A Report on the State of Hinduism in Religious Education in UK Schools

0 1 A report on the state of Hinduism in Religious Education in UK schools Published 14th January 2021 INSIGHT UK www.insightuk.org Email: [email protected] 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 INTRODUCTION 8 PROJECT METHODOLOGY 12 PHASE 1 - RESEARCH PHASE 14 Key findings 14 PHASE 2 - CONSULTATION PHASE 19 Key Findings 19 PHASE 3 - SURVEY PHASE 23 Survey findings - Primary schools (Year 1-6) 24 Survey findings - Key stage 3 (Year 7-9) 29 Survey findings - Key stage 4 (Year 10-11) 33 Survey findings - Standing Advisory Councils on RE (SACRE) section 40 Survey findings - School Governor section 41 General questions for Hindu Parents 42 KEY FINDINGS FROM SURVEY PHASE 46 RECOMMENDATIONS 50 WHAT NEXT? 54 REFERENCES 56 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 59 3 4 Executive summary INSIGHT UK is pleased to present the report on the state of Hinduism in Religious Education (RE) in UK schools. INSIGHT UK is an organisation that aims to address the concerns of the British Hindu and British Indian communities. In 2020, INSIGHT UK conducted a project with a team comprised of highly experienced members of the Hindu community, amongst which are well- known academics, including professors and teachers. The project goal was to assess the current state of Hinduism in RE in UK schools and recommend changes to improve it. This project was supported by Hindu Council UK, Hindu Forum of Britain, Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (UK), National Council of Hindu Temples UK and Vishwa Hindu Parishad (UK). We are thankful to everyone who has contributed to this project. Key Findings The main findings from this survey concluded: • 97% of survey respondents say it is important and paramount for their child to learn about Hinduism. -

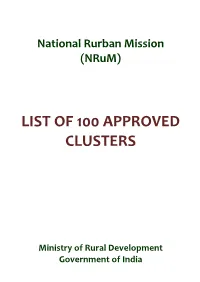

List of 100 Approved Clusters

National Rurban Mission (NRuM) LIST OF 100 APPROVED CLUSTERS Ministry of Rural Development Government of India NORTHERN REGION S.N. Name of the District Name of the Sub-District Name of the Cluster Haryana 1 Karnal Assandh Balla 2 Ambala Barara Barara 3 Fatehabad Tohana Samain 4 Jind Narwana Uchana Khurd 5 Rewari Kosli Kosli 6 Jhajjar Bahadurgarh Badli Uttar Pradesh 1 Chitrakoot Mau Mau Mustkil 2 Chitrakoot Karwi Kashai 3 Ghaziabad Ghaziabad Dasna Dehat 4 Kushinagar Tumkuhi Raj Bans Gaon 5 Gautam Buddha Nagar Dadri Chitehera 6 Firozabad Tundla Rudhau Mustkil Patehara Kalan Urf Kubari 7 Mirzapur Marihan Pate 8 Bagpat Baraut Silana 9 Allahabad Koraon Barokhar 10 Lucknow Lucknow Juggaur Himachal Pradesh 1 Kinnaur Sangla Sangla 2 Solan Kandaghat Hinner Jammu & Kashmir 1 Jammu Jammu Gole Gujral 2 Kupwara Kupwara Khumryal Uttarakhand 1 Dehradun Rishikesh Athoorvala 2 Haridwar Haridwar Bhaktanpur-Abidpur Punjab 1 Bhatinda Rampura Phul Dhapali 2 Amritsar Ajnala Harsa Chhina EASTERN REGION S.No Name of the District Name of the Sub-District Name of the Cluster Bihar 1 Patna Sampatchak Bairia 2 Gaya Manpur Nauranga 3 Rohtas Kochas Kuchhila 4 Saharsa Sonbarsa Sonbarsa Chhattisgarh 1 Bastar Jagdapur Madpal (T) 2 Dhamtari Dhamtari Loharsi 3 Rajnandgaon Dongargarh Murmunda (T) 4 Kawardha Pandariya Kunda Jharkhand 1 Giridih Giridih Bhandaridh 2 Dhanbad Baliapur Palani 3 Purbi Singhbhum Ghatshila Dharambahd (T) Odisha 1 Jharsuguda Kolabira Samasingha 2 Khurda Banapur Banapur 3 hhauttack Banki Tala Basta 4 Mayurbhanj Thakurmunda Thakurmunda (T) 5 Kalahandi -

Temple Foods of India’’

Report on stall of “Temple foods of India’’ National “Eat Right Mela” from 14th to 16th December, 2018 at IGNCA near India Gate, New Delhi The first National “Eat Right Mela” is being organized from 14th to 16th December, 2018 at IGNCA near India Gate, New Delhi. This Mela is being held along with the established and well-known ‘Street Food Festival’ organized by NASVI since the past 10 years. One of the attractions was the stall on “Temple Foods of India” under the pavilion “Flavours of India” which showcased cuisines of India’s most famous temples and the variety of different prasad offered to pilgrims. Following are 13 famous Temples from across India participated in the festival: S. No. Name of temple 1 Arulmigu Meenakshi Sundareshwarar Temple, Madura i, Tamil Nadu 2 Dhandayuthapani Swamy Temple,Palani,Tamil Nadu 3 Ramanathaswamy Temple, Rameshwaram, Tamil Nadu 4 Arunachaleshwarar Temple, Thiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu 5 ISKCON Temple, Delhi 6 Chittaranjan Park Kali Mandir, Delhi 7 Gurudwara, Delhi 8 Somnath Temple, Gujarat 9 Shree Kashtubhanjan Hanumanji Temple, Gujarat 10 Ambaji Temple, Gujarat 11 Swaminarayan temple BAPS, Maharashtra 12 Shirdi Sai Baba Temple, Maharashtra 13 Shrinathji Mandir Nathdwara, Rajasthan Some of the temples are associated with FSSAI under BHOG (Blissful Hygienic Offering to God) which focuses on the hygienic preparation of prasad and training & capacity building of the Temple food ecosystem to ensure the same. Day 1 at Eat Right Mela 14 dec to 16 dec, 2018 Four Temples from Tamil Nadu had brought different kind of Prasad. And these temples have already implemented FSMS in their temples. -

Saurashra Tour

www.tirthholidays.com Saurashra Tour Jamnagar, Dwarka, Somnath, Rajkot and Ahmedabad 7 Nights / 8 Days Itinerary Code: THSA8N9D Day 1:- ARRIVE AHMEDABAD * ON TO JAMNAGAR (313 KM/ APPROX. 8 HOUR DRIVE) Welcome to Ahmedabad, the largest city in Gujarat. On arrival at airport / railway station in Ahmedabad, you will be met and transferred to Jamnagar. On arrival, check-in to the hotel. The rest of the evening is at leisure for independent activities. Overnight in Jamnagar - None (Meals on your own). Day 2:- ON TO DWARKA (156 KM/ APPROX. 3 HOUR DRIVE ) This morning, drive to Dwarka. En route, visit the Lakhota Lake, liveliest in the evenings, when people relax around the lake to enjoy the breeze and a chai, kulfi, or chaat from one of the many food stands, and at night the lake is beautifully lit. Lakhota Museum, originally designed as a fort such that soldiers posted around it could fend off an invading enemy army with the lake acting as a moat, the tower known as Lakhota Palace now houses the Lakhota Museum and Bala Hanuman Temple, on the southeast corner of the lake is the Bala Hanuman temple, famous for its continuous chanting of the 'Sri Ram, Jai Ram, Jai Jai Ram', for which it is even listed in the Guinness Book of World Records. Continue to Dwarka, on arrival check in to your hotel. Later, visit Rukmini Temple and Dwarkadeesh Temples, the main temple at Dwarka, also known as Jagat Mandir. The grandeur of the temple is enhanced by the flight of 56 steps leading to the rear side of the edifice on the side of the river Gomti. -

POSITION of SURVEYS in PROGRESS (25 Nos) "On 26Th,Sept

POSITION OF SURVEYS IN PROGRESS (25 nos) "on 26th,Sept" S BB Survey State Target Status Remarks Unit N NO Sanction Year : 2011-12 1 1 RECT survey for New BG bye HR& RJ Done Work Santioned in year Length - 6.0 km, Cost - Dy.CE pass line at Rewari from 2013-14.Appearing in PB Rs.33.608 cr, ROR = /III/JP Alwar-Sadulpur (8 km). 2014-15,vide item 26. (+) 18.23%. 2 2 Updating survey between RJ Done Survey report sent to Rly. Length - 92.00 km, Dy.CE /I/AII Devli-Tonk-Sakatpura New Bd. on 08.01.13. Cost - Rs. 705.42 cr, BG line (62 km). ROR = (-) 17.76%. 3 3 New line between Barmer- RJ March,15 Estimate Prepared on dt: Length - 92.00 km, DY CE/JU Palanpur. , ROR calculated on dt: Cost - Rs. 705.42 cr, & under Finance vetting since ROR = ( -) 17.76%. 4 4 RECT survey for New BG line HR& RJ March,15 Estimate Prepared on dt: Length - 92.00 km, Dy CE/ between Alwar-Charkhi Dadri. , ROR calculated on dt: Cost - Rs. 705.42 cr, III/JP & under Finance vetting since ROR = (-) 17.76%. 5 5 New Line between Taranga- GJ& RJ Dec,14 Estimate prepared & DY CE/ Abu Road via Ambaji. submitted for approval of Survey /JP CSTE/C & CE/C/III on 15th,Sept. 6 7 RECT survey for a New line GJ & RJ March,15 Work of fixing of alignment DY CE/ between Palanpur-Ambaji-Abu is under progress. Survey /JP Road (76 km) 7 8 Up dating for NL between RAJ, Punj Details not available DY CE/HMH Abohar-Tohana via Ftehabad & DLI (207 Km). -

Download the Conference Proceedings

Contents Introduction.................................................................. 3 Keynote Address .......................................................... 5 Workshops Summaries................................................. 8 a. Mandirs and Governance b. Mandirs and External Representation and Engagement c. Mandirs and Youth d. Mandirs and Promotion of Hindu Dharma e. Mandirs andSschool visits f. Mandirs and Sewa Concluding Address...................................................... 20 Conference feedback and statistics.............................. 23 Contact details............................................................. 25 Resource list................................................................. 26 a. Hindu Literature bookshop b. Hindu Dharma exhibition c. Chaplaincy booklet d. Voices course online Special session on Covid-19......................................... Addendum Copyright - Vishwa Hindu Parishd (UK) - 2020 Image credits: Images of various mandirs are taken from the respective mandir websites. HMEC UK 2020 Page 2 Introduction Namaste & Welcome! This booklet is a summary of the proceedings The Need for Hindu Mandir of the inaugural Hindu Mandir Executives’ Executives Conference UK Conference in the UK (HMEC-UK) held on 4th October 2020. As many of these challenges are fairly common it would be beneficial for mandir executives Why HMEC UK? (President, Secretary, Treasurer, etc) to meet on a common platform to discuss, share, learn and It is estimated that there are around 250 network so that collectively we can work and Hindu mandirs in the UK representing various help each other. sampradayas and Bharatiya languages/provinces. They are the pillars of our dharmic traditions and In view of the above VHP UK organised the cultural values, centres of social activities and the Hindu Mandir Executives Conference UK, a 3 face of our community for the outside world. hour online conference on Sunday 4 October 2020. The conference had eminent speakers, In fact, they are the heart of our samaj which workshops and Q&A sessions. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Theme 3E: the Impact of Migration on Hindu Identity and the Challenges of Being a Religious and Ethnic Minority in Britain Contents

GCE A LEVEL Eduqas A-LEVEL RELIGIOUS STUDIES Theme 3E: The impact of migration on Hindu identity and the challenges of being a religious and ethnic minority in Britain Contents Glossary Key Terms 3 The meaning of Hindu identity in terms of belief, practice, lifestyle, 4 worship and conduct Beliefs, practice, lifestyle, worship and conduct – how do they inform 6 Hindu identity in the UK? Possible conflict of traditional Hinduism with popular culture 9 Difficulties of practising Hinduism in a non-Hindu society 12 Issues for discussion 14 Other Useful Resources 15 2 Glossary Key Terms International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) – Hindu Vaishnava movement, founded in the USA in 1965 by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. It follows the tradition of Caitanya, and aims for the state of permanent Krishna consciousness. Dancing and chanting the maha-mantra are important features of worship. It welcomes non-Indians who are willing to commit to its stringent rule and regulations. Ramakrishna Mission – A volunteer organisation founded by Vivekananda. It is involved in a number of areas such as health care, disaster relief and rural management and bases its work on the principles of karma yoga Santana Dharma – Eternal law; understanding of Hinduism as a universal principle that all should obey. Other useful terms Sampradaya – a tradition within Hinduism following the teachings of a specific teacher or guru e.g. Swaminarayan 3 The meaning of Hindu identity in terms of belief, practice, lifestyle, worship and conduct The term ‘Hindu’ was first used by Persians to denote the people living beyond the river Sindhu (Indus), so the term was purely to identify Indians and not their religion. -

Newsletter March 2010

Other News Volume 2 Issue 2 Our Annual General Meeting will be held on 22nd May 2010. Food and light entertainment will be provided. Please confirm your attendance Newsletter with a committee member so that we can plan for the catering. March 2010 Most of the current committee will be either stepping down or their term of office expires. Therefore a new committee will be needed to continue the work of Sakhi Milap Hertfordshire. Anyone interested in joining the committee, Update please contact Gabi or Hansa for more information. Nomination forms are Since our Annual Review in June 2009, we have completed a survey to enclosed with this newsletter. Please ensure that you are a current member in identify the member and Indian community needs. The survey consultation order to join the committee. in November 2009 was supported by Gujarati Hindu Mens Association. It was Membership renewal for 2010/11 is due in May. Renewal forms will be done with the possibility in mind of having an accessible and amenable long- available at the AGM. term base for regular activities. The returned questionnaires have provided some good feedback and suggestions for activities, including: cultural activities Satsung Mandal recently had an event in celebration and recognition of the for all ages; celebrations and special services and practical workshops people present in the Indian community in Stevenage in the age group of 70+. (cookery, sewing, etc). A number of skills from those who responded have also They also recognised and celebrated of the contribution made by the Gujurati been identified which could be used in a new project.