Numismatics in the Netherlands – a Personal Impression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The California Numismatist

Numismatic Fall 2008 California State Association of V. 5, No. 3 Numismatic Southern California $5.00 Association The California Numismatist The California Numismatist Offi cial Publication of the California State Numismatic Association and the Numismatic Association of Southern California Fall 2008, Volume 5, Number 3 About the Cover The California Numismatist Staff Images from our three main Editor Greg Burns articles grace our cover against a P.O. Box 1181 backdrop relating to a surprising de- Claremont, CA 91711 velopment in the printing of our little [email protected] journal: color! This is the fi rst issue Club Reports Virginia Bourke with the interior pages printed in color, South 10601 Vista Camino though the cover has been in color Lakeside, CA 92040 since the inception of TCN in 2004 [email protected] (starting in 2002 The NASC Quarterly, one of our predecessor publications, Club Reports Michael S. Turrini also started having color covers). North P.O. Box 4104 Please do write and let us know Vallejo, CA 94590 what you think about the new look. [email protected] While the expense is a bit more, Advertising Lila Anderson there’s such an improvement in aes- P.O. Box 365 thetics we’re inclined to keep it up. Grover Beach, CA 93483 [email protected] Visit Us on the Web The California Numismatist has a Web site at www.CalNumismatist.com. You can fi nd the offi cial scoop there in between issues. Also, both CSNA and NASC main- tain their own Web sites at: www.Calcoin.org www.NASC.net 2 The California Numismatist • Fall 2008 Contents Articles Wells Fargo & Company Jim Hunt ............................................................................................................10 Through the Numismatic Glass: This 19th Century Cent Design Lasted for Only One Year Dr. -

Highest Honor Awards Given to Numismatists Making a Difference

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Friday, July 27, 2018 CONTACT: Amanda Miller Telephone: 719-482-9871 E-mail: [email protected] Highest Honor Awards Given to Numismatists Making a Difference The American Numismatic Association (ANA) is recognizing several numismatists who not only lead by example, but pave new pathways within the numismatic hobby. Recognized for their dedication, hard work, passion and contributions, these recipients will be recognized at the World’s Fair of MoneyⓇ in Philadelphia, Aug. 14-18. Those being recognized are: Cindy Wibker for the Farran Zerbe Memorial Award for Distinguished Service David J. McCarthy for Numismatist of the Year Abigail Zechman for the Young Numismatist of the Year Mark Lighterman for the Lifetime Achievement Award The Farran Zerbe Memorial Award for Distinguished Service is the highest honor conferred by the American Numismatic Association. It is given in recognition of numerous years of outstanding, dedicated service to numismatics. Cindy Wibker is the recipient of this year’s award. For 25 years, Wibker has dedicated her career to Florida United Numismatists (FUN) as convention coordinator, organizing one of the premier shows in the country. This is no easy task, as FUN’s annual January show regularly draws an average of 10,000 attendees over four days, and its summer event, held each July, welcomes about 3,000 hobbyists. Born in Shreveport, Louisiana, the young Wibker enjoyed filling Whitman nickel and cent folders with pocket change and acquiring specimens through mail-order businesses. However, her mind turned to other pursuits. Growing up she enjoyed spending time outside playing different sports, going to games, spending time with her family and riding her bike. -

Download This Issue

Your Treasures are in Specialists in high quality ancient, medieval, and early Good Hands with us modern coins and medals. First established as a numismatic trading Auctions in Switzerland, company in 1971, today we have achieved a yearly price list, appraisals, solid reputation among the leading coin and medal auction houses of Europe. More than purchases and sales by 10,000 clients worldwide place their trust private treaty. zürich, switzerland Baltic States, City of Riga. Auction 135 in us. Our company’s fi rst auction was held Under Sweden. Charles X. Gustav, 1654-1660. 5 ducats “1645” (1654). in 1985, and we can look back on a positive Estimate: € 15,000. Price realized: € 70,000. track record of over 180 auctions since that time. Four times a year, the Künker auction gallery becomes a major rendezvous for numismatic afi cionados. This is where several thousand bidders regularly participate in our auctions. • We buy your gold assets at a fair, daily market price • International customer care Auction III • Yearly over 20,000 objects in Ancient Greek, Roman, our auctions Byzantine & Early European coins and medals of the • Large selection of gold coins highest quality. • Top quality color printed catalogues May 10th 2011 Russian Empire. Auction 135 Alexander I., 1801-1825. Gold medal of 48 ducats, 1814, by tsarina in the morning M. Feodorovna for Alexander I. in Zürich Estimate: € 30,000. Price realized: € 220,000. Auction IV The BCD Collection Profi t from our experience of more than 180 successful auctions – of Thessaly. scaled consign your coins and medals! down May 10th 2011 Tel.: +49 541 96 20 20 in the afternoon Roman Empire. -

Numismatics—An Ancient Science

conttributions from The Museum of History AxVd Technologv: Paper 32 Numismatics—an Ancient Science A Survey of its History EIvn\i EIr\j CLini-Stcj\t)iiHi INTRODUCTION 2 evolution ol- a sciknch .3 beginnings oe coin coi.i.ec'l'inc s middle aces and early renaissance ii renaissan(.:e and CINQLECENTO I5 SEN'ENTEENTH CEN lEIRV 22 EICHIEENTH CENTURY 25 EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY 34 -11 MODERN TRENDS AND ACCOMI'LISI I M EN TS NUMISMAITCS IN HIE UNI I ED STATES 60 LITERATURE CITED 6S NUMISMATICS-AN ANCIENT SCIENCE A Survey of its History By Elvira EUt^i Clain-Stefaiielli INTRODUCTION This study has been prompted l)y the author's within specific areas. Citations of their books and observation that many people resjard nuinismaties articles are given in shortened form in the footnotes, simply as coin coUectins;, a pleasant hobby for young- willi full references appearing at the end of the paper. sters or retired persons. The holder of siicii a view- Because coin collections have supplied the raw point is unaware of the sco[)e and accomplishments of material for much in\estigation, the histories of some a historical investi<;ation that traces cultural evolution of the major private and public collections also have throus^h one of the basic aspects of everyday human been included in this survey. life: money. Seen as a reflection of past aspirations In my research, I have had an excellent guide in and accomplishments, coins are invaluable sources Ernest Babelon's chapter "l.a nutnismati(]ue et son for scholarly research, but few people are aware of histoire," published in 1901 as part of the first volume the tremendous amount of work done in this field by of his Trailf des monnaies grecques et romaines: Theorie past generations. -

MEDICAL NUMISMATICS* by FIELDING H

MEDICAL NUMISMATICS* By FIELDING H. GARRISON, M.D. LIEUTENANT COLONEL, MEDICAL CORPS, U. S. ARMY WASHINGTON, D. C. T is said that Billroth, in looking over were struck off regularly by the old Acad- a collection of medical medals, observed emy of Medicine of Paris to commemorate that “hardly a single one of them had the biennial election of each new Dean of been struck off to commemorate any- the Paris Medical Faculty, and copies of thing more than respectable mediocrity.” these jetons, in silver or bronze, were ILike all epigrams and stories of the ben presented to all the members of the Faculty. trovato type, the assertion has a shade of The Dean was not a professor in the Faculty exaggeration and an element of truth. but its chief administrative officer, hence The earlier medical medals tended to a prominent rather than an eminent figure commemorate things rather than people, in the history of early French medicine. later on, physicians prominent on account The Academy of Medicine (Paris) possesses of their connection with institutions and 108 of these rare pieces. The numismatic societies, finally physicians recognized as collection of the Army Medical Museum eminent by reason of their contributions (Washington) has ninety-one. The last to to scientific medicine. The same tendency be struck off was that of Claude Bourru, is noticeable throughout the history of who was Dean for three successive terms medicine with regard to medical authorship. (1788-1793). When, in 1793, the scientific Before Hippocrates, recorded medicine, societies, -

Heritage Auctions | Fall 2020 $7.9 9

HERITAGE AUCTIONS | FALL 2020 $7.9 9 DREW HECHT Election Season Energizes Collectors of Political Paper Money Movie Posters Auction Previews Memorabilia International Notes Collecting Strategies of Peter Lindeman, Lou Gehrig, Command Top Prices a Hollywood Producer Mike Coltrane, Justin Schiller features 32 Collecting With Style Hollywood producer Mike Kaplan has always had an eye for the elements that make a movie poster great By Hector Cantú Portrait by Deborah Hardee 36 Worldly Treasures As the largest numismatic auctioneer of international banknotes, Heritage Auctions has notched some impressive prices realized By Dustin Johnston 42 Cover Story: Collecting Democracy Upcoming election is a great time to discover how political memorabilia can be affordable, rewarding and fun By David Seideman Portrait by William Thomas Cain 51 To Serve and Protect As long as you have the space and right conditions, consider keeping your precious wine collection at home By Debbie Carlson China People’s Republic 10,000 Yuan 1951 (detail) from “Worldly Treasures,” page 36 From left: New Heritage headquarters, page 10; Lou Gehrig, page 21; Peter Lindeman, page 28 Auction Previews Columns 20 28 57 How to Bid Fine Jewelry: The Private World Currency: Hiding in Plain Sight Collection of Peter Lindeman Designers of Seychelles Rupees created one of 21 Artisan looks back on a career brim- hobby’s more popular collectibles with a little Sports Collectibles: ming with exquisite pieces, acco- subliminal assistance Baseball History lades and special friends By Craig -

Early Christian Numismatics and Other Antiquarian Tracts, Charles W

467. NUMISMATICS. Early Christian Numismatics, and other Antiquarian Tracts. By C. W. King. Illustrated. London, 1873. Svo, cloth, scarce • • • .$3.50 Cornell University Library BR131 .K52 Early Christian numismatics and other a 3 1924 029 242 041 olln Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029242041 J Jobbms hth ; EARLY CHRISTIAN NUMISMATICS, OTHER ANTIQUARIAN TRACTS. By C. W. |ING, M.A., AUTHOR OP ' ANTIQUE GEMS,' ETC. 1 Csesaris vexilla linquunt, eligunt signum Crucis Proque ventosis draconum quae gerebant palliis, Eligunt insigne lignum quod Draconem subdidit." Prudentius. LONDON: BELL & DALDY, YOKE STEEET, COVENT GABDEN. : LONDON PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFOKD STREET AKD CHARING C110SS Constantine, decus mundi, lux aurea ssecli, " Quis tua mixta canat mira pietate tropa;a ! Optatian. PREFACE. T^E little treatise which gives its title to the present volume originated in an application made to me by our Regius Professor of Divinity to point out to him any history of the introduction of Christian types upon the Roman coinage. The only book of that nature to which I was able to refer him was Dr. Walsh's brief essay ' On the Coins, &c, illus- trating the Progress of Christianity in the Early Ages/ published so long ago as 1828 ; and which, so far as I have been able' to ascertain, remains the only work in any language that takes for its ex- clusive subject this truly interesting and fertile province of Numismatics. -

The Back Page Numismatics – Geeks Or Greeks

The Back Page The Back Page will look at topics and items of interest , but from not quite THE RIGHT ANGLE. Numismatics – Geeks or Greeks ? There was much excitement at the last Regular Meeting as a young inexperienced Office-bearer brought down the latest addition to his collection. An Alexander 3rd. coin. It was about the size of a five pence piece and was in quite good condition. Everyone had a look and an opinion as to what it was. Then a member of the Lodge who is a well known collector (of everything) was asked for his opinion. There was a hush in the committee room as he adjusted his glasses and looking at it closely up to the light and announced “ it could be Greek”. Everyone was stunned by his encyclopaedic mind, until the young inexperienced Office-bearer exclaimed, Alas, Alas, Alasdair, “ Alexander the third wasn`t Greek !” He then gave a machine gun speed resume of Alexander the third King of Scots from 1249 to 1286 ! Including his victory at the Battle of Largs in 1263! The Collector was ruffled, who was this new young Geek – who knew his Greeks ? was he right that Alexander wasn`t Greek ? The Collector in reply said that there was a Greek called Alexander, who was this Greek ? was he a Geek ? ..... Darts. Sharpen your tips ……. The Big Contest is back ……. World Championship Darts here on a Friday night …………… Get your name on Inside this issue. the entry sheet. Lodge St. Bryde News. Freemasonry in Serbia Provincial News Homepage- http://www.stbryde.co.uk 8 Serbia. -

E-Newsletter

Contents International Numismatic 01 The President’s Note 02 Reports from institutions e-Newsletter 04 Congresses and Meetings 08 Research programs 08 Exhibitions 09 Websites 10 New publications INeN 18 - January 2015 17 Personalia 18 Obituaries 20 INC Annual Travel Grant 21 INeN contribute and suscribe The President’s Note - Il saluto del Presidente Dear INC members, dear colleagues and friends, On behalf of the INC I wish you that in these times of polarization on a multitude of issues all a happy and prosperous about cultural property, we can find common ground and New Year! It is an important collaborate to the benefit of numismatics. year for our Council and for the numismatic community The INC Committee will meet in Taormina in March to at large since it is the year make sure that everything will be ready to welcome you in of our XVth International September and make your participation as productive and Congress, which will take pleasant as possible. I also want to thank the Scientific place in Taormina, September and Organizing Committee for all their work: we are in 21-25, 2015. It is, as you a period of recession and economic instability and the know, the most important financing of this Congress is one of the most challenging event for the INC, and its the INC ever had to face. Governments can no longer organization, as well as the afford to be as generous as Spain was in 2003 and offer Dr. Carmen Arnold-Biucchi publication of the Survey of a spectacular Palace of Congresses for free. -

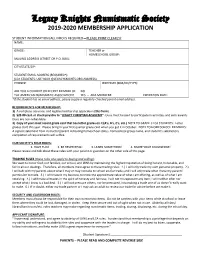

Legacy Knights Numismatic Society 2019-2020 MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION

Legacy Knights Numismatic Society 2019-2020 MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION STUDENT INFORMATION (ALL INFO IS REQUIRED—PLEASE PRINT CLEARLY): NAME: GRADE: TEACHER or HOMESCHOOL GROUP: MAILING ADDRESS (STREET OR P.O. BOX): CITY/STATE/ZIP: STUDENT EMAIL ADDRESS (REQUIRED*): (LCA STUDENTS, USE YOUR @LEGACYKNIGHTS.ORG ADDRESS) PHONE#: BIRTHDAY (MM/DD/YYYY): ARE YOU A CURRENT OR RECENT MEMBER OF NO THE AMERICAN NUMISMATIC ASSOCIATION? YES -- ANA MEMBER#: EXPIRATION DATE: *If the student has no email address, please supply a regularly-checked parent email address. REQUIREMENTS FOR MEMBERSHIP: 1) A complete, accurate, and legible membership application (this form). 2) $25.00 cash or check payable to “LEGACY CHRISTIAN ACADEMY”. Dues must be paid to participate in activities and earn awards. Dues are non-refundable. 3) Copy of your most recent grade card that has letter grades on it (A’s, B’s, C’s, etc.) NOTE TO GRADE 3 LCA STUDENTS: Letter grades start this year. Please bring in your first quarter grade card when you get it in October. NOTE TO HOMESCHOOL MEMBERS: A signed statement from instructor/parent indicating homeschool status, homeschool group name, and student’s satisfactory completion of requirements will suffice. OUR SOCIETY’S FOUR RULES: 1. HAVE FUN! 2. BE RESPECTFUL! 3. LEARN SOMETHING! 4. SHARE YOUR KNOWLEDGE! Please review and talk about these rules with your parent or guardian on the other side of this page. TRADING RULES (these rules also apply to buying and selling): We want to honor God, our families, our school, and LKNS by maintaining the highest reputation of being honest, honorable, and fair in all our dealings. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK ---X Universal Grading Service, J

Case 1:08-cv-03557-CPS-RML Document 66 Filed 06/10/09 Page 1 of 57 PageID #: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ----------------------------------------X Universal Grading Service, John Callandrello, Joseph Komito and Vadim Kirichenko, individually and on behalf of others similarly situated, Plaintiffs, 08-CV-3557 (CPS) - against - MEMORANDUM OPINION eBay, Inc., American Numismatic AND ORDER Association, Professional Numismatists Guild, Inc., and Barry Stuppler & Company, LLC, Defendants. ----------------------------------------X SIFTON, Senior Judge. Plaintiffs Universal Grading Service (“USG”), John Callandrello, Joseph Komito and Vadim Kirichenko commenced this putative class action1 on August 29, 2008 against defendants eBay, Inc. (“eBay”), American Numismatic Association (“ANA”), Professional Numismatists Guild, Inc. (“PNG”), and Barry Stuppler 1 Plaintiffs describe two putative classes in their Second Amended Complaint (“SAC”). The first class includes “all companies and individuals who provide coin grading services on [sic] the market for coin auctions to the public at large and who have not been certified by eBay as ‘the authorized grading company’ pursuant to eBay’s Counterfeit Currency and Stamps policy and who are interested in pursuing this lawsuit.” SAC ¶ 82. The class period is from January 2004 to the present. Id. ¶ 83. The second class includes “all U.S. based eBay account holders who utilized coin grading services to sell coins on eBay to the public at large which have not been certified by eBay as ‘the authorized grading companies’ pursuant to eBay’s Counterfeit Currency and Stamps policy and who, as a result, have not been able to list their coins on eBay as ‘certified’ and who are interested in pursuing this lawsuit.” Id. -

A B C D E F G 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

A B C D E F G 1 Catalog Name as Per Box: Missing numbers: Damaged numbers: Notes: 2 3 Alpert, Stephen #1-4, 6-15 4 American Coin and Stamp Brokerage Many between #6-56 5 American Numismatic Rarities September 13, 2003 announced, presumed missing 6 Ancient Coins (Berkeley, CA) #1, 2 of #12-14, 16, 17, 19 7 Ancient Coin Clubof America, The #24 8 Ancient Gens see lists 9 Antioch Associates #42-46 10 Auction '79-'90 ("Apostrophe Auction") moved from Superior. Change catalog 11 Berk, Harlan J. #15-18, 37-44, 65, 81, 110, 125, 138, 139, 162, 164, 165. last 3 in catalogue, not shelfsee also Berk - Gemini 12 Bosco, Paul #13, 15, 20, 23 13 Bourne, Remy #1, 6, 10 14 Bowers & Merena Mar 26-28, 1984 smashed, Aug 26-29, 1987 spine, Oct 12-13, 1987 back ripped off, 15 Mar 1989 heavily worn, Mar&Jun 1991, May 1993 16 Bullowa, C. E. 17 Cederlind, Tom #108, 119, 122-7, 129-130, 134-5, 137, 140, 143 18 Christie's (New York) 1984-1987 spines 19 Clark's 1 of #1-2, #6, 1 of #8-12, 1 of #16-19, 28, 42, 44, 45, 48, 50, 21, 56, 57, 59, 60, 63, 65, 72, 74, 75, 78, 86, 95, 98, 103, 106, 107 20 Classical Numismatic Group #43 ripped back cover 21 Cobb cf Northern California Numismatic Association 22 Cohasco #32, 33, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41 Box unlabeled by number 23 (Stack's) Coin Galleries Mar 1971, Jul 1975, Sep 1981, Apr 1986, May 1987, Feb 2001 24 Colonial Coins Inc.