'The Barbary Coast in a Barbarous Land' Policing Vice in San

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chief Thomas J.Cahill: a Life in Review

SFGov Accessibility Police Department Chief Thomas J.Cahill: A Life In Review In the San Francisco Police Academy yearbook for August, 1942, on a page entitled Honors, J.Von Nostitz was chosen Most likely to become Chief of Traffic, G.K. Hoover was Most likely to become Chief of Detectives, and J.C. Cook was given the somewhat dubious honor of being Most likely to serve 40 years, presumably in the Department. In retrospect, the person who compiled these predictions weren't much on target, with one exception. Smack in the middle of the page filled with rather clever drawings of each of the officers, his name and prediction typed below, is a sketch of a curlyhaired, oval faced youth: T.J. Cahill, Most likely to become Chief of Police. Thomas Joseph Cahill has the distinction of having the longest tenure as Chief of Police in San Francisco's history, serving under three mayors – George Christopher, John Shelley, and Joseph Alioto through decades that saw tremendous social changes and upheavals. In the Richmond district flat that the shares with Felipa, his second wife of 28 years, there's a large 1967 portrait of him hanging on the wall. You can still see the firmness, directness, and sense of humor evident in the portrait in his face. Now 88, he's alert and strong, his hair white but still wavy. With a touch of the brogue that's never left him, he reminisced over a career that spanned 30 years. Tom was born on June 8, 1910 on Montana Street on the North Side of Chicago. -

Hadley Roff Hadley Roff: a Life in Politics, Government and Public Service

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Hadley Roff Hadley Roff: A Life in Politics, Government and Public Service Interviews conducted by Lisa Rubens in 2012 and 2013 Copyright © 2017 by The Regents of the University of California Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Hadley Roff dated June 21, 2013. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Regional Oral History Office University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Joseph L. Alioto CHANGING THE FACE OF SAN FRANCISCO: MAYOR 1968-1976, AND ANTITRUST TRIAL LAWYER With an Introduction by John De Luca Interviews conducted by Carole Hicke in 1991 Copyright 0 1999 by The Regents of the University of California, the California Historical Society, and the Ninth Judicial Curcuit Historical Society Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the California Historical Society, the Ninth Judicial Circuit Historical Society, The Regents of the University of California, and Kathleen Alioto. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. -

50Th Anniversary Report

GrantGrantss FORFOR THE THE ArtsArts The First 50 Years Acknowledgements Grants for the Arts appreciates the many who contributed recollections to this retrospective. We acknowledge all who have been important in our first 50 years, the hundreds of grantees, public and private donors, fellow funders, and the city’s many far-sighted policymakers and elected officials whose guidance and support over the decades have helped ensure GFTA’s continuing success. Edwin M. Lee, Mayor of San Francisco Amy L. Brown, Acting City Administrator Grants for the Arts Citizens Advisory Committee Clara Chun Daniels, Attorney, Kirin Law Group Berta Concha, Community Consultant Donna Ficarrotta, Managing Director, Union Square Business Improvement District Dan Goldes, Strategic Advisor, San Francisco Travel Linc King,Vice President and General Manager, Beach Blanket Babylon Ebony McKinney, Emerging Arts Professionals Jackie Nemerovski, Arts Manager/Consultant Tere Romo, Program Officer for Arts and Culture, The San Francisco Foundation Charles Roppel, Certified Professional Life Coach Ruth Williams, Program Officer, Community Technology Foundation Grants for the Arts Staff Kary Schulman, Director Renee Hayes, Associate Director Valerie Tookes, Senior Finance and Operations Manager Khan Wong, Senior Program Manager Brett Conner, Administration and Communications Manager Grants for the Arts … The First 50 Years Produced by San Francisco Study Center Reporter and Writer: Marjorie Beggs Editor: Geoff Link Designer: Lenny Limjoco Grants for the Arts’ first 25 years is documented in detail in “The San Francisco Hotel Tax Fund: Twenty-Five Years of Innovative Funding,” by Cobbett Steinberg, published in the Spring 1986 issue of Encore, the quarterly magazine of the San Francisco Performing Arts Library and Museum. -

Deddemocrat00portrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the Regents of the University of California and Julia Gorman Porter dated October 27, 1975. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California Berkeley, No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, 486 Library, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Women in Politics Oral History Project Julia Gorman Porter DEDICATED DEMOCRAT AND CITY PLANNER, 1941-1975 With an Introduction by Kevin Starr An Interview Conducted by Gabrielle Morris Copy No. / 1977 by The Regents of the University of California San Francisco Chronicle September 15, 1990 Julia Gorman Porter Julia Gorman Porter, a well- known Democratic Party leader and longtime member of the San Francisco Planning Commission, died August 22 at the age of 93. Mrs. Porter, who was born in San Francisco, had been active in Democratic Party affairs begin ning in the 1930s and worked to elect President Franklin Roose velt. She became prominent in civ ic policy-making when she was ap pointed to the Planning Commis sion in 1943 by Mayor Roger La- pham. -

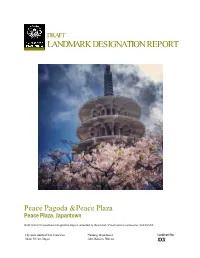

Draft Landmark Designation Report

DRAFT LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Peace Pagoda & Peace Plaza Peace Plaza, Japantown Draft Article 10 Landmark Designation Report submitted to the Historic Preservation Commission, XXXXXXXX City and County of San Francisco Planning Department Landmark No. Edwin M. Lee, Mayor John Rahaim, Director XXX Cover: Peace Pagoda, 2013. The Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) is a seven-member body that makes recommendations to the Board of Supervisors regarding the designation of landmark buildings and districts. The regulations governing landmarks and landmark districts are found in Article 10 of the Planning Code. The HPC is staffed by the San Francisco Planning Department. This Draft Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment during the initiation and designation process. Only language contained within the Article 10 designation ordinance, adopted by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, should be regarded as final. CONTENTS OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 BUILDING DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Peace Pagoda ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 Peace Plaza .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Annual Report for Fiscal Year 2002-03

Rules, Policies and Procedures Administration Civil Service Commission Rules Foremost in the Commission’s agenda is to modernize and streamline the Civil Service Commission Rules, to protect the civil service merit system, and to control costs which result from practices which may not be conducive to the efficient operation of a department. The Civil Service Commission recognizes the need to Morgan R. Gorrono, President Rosabella Safont, Vice President Donald A. Casper, Commissioner Adrienne Pon, Commissioner Linda Richardson, Commissioner Commission Staff Kate Favetti, Executive Officer Yvette Gamble, Senior Personnel Analyst Elizabeth García, Administrative Assistant Lizzette Henríquez, Rules, Personnel & Office Coordinator Gene D. Rucker, Labor Negotiator Anita Sanchez, Assistant Executive Officer Gloria Sheppard, Appeals Coordinator make our workforce more efficient by providing managers with the necessary tools which conform with and anticipate changes in the work environment so as to avoid expending unnecessary personnel time and resources on duplicative or archaic practices. Civil Service Commission Annual Report 2002-2003 1 Commission Meetings The Civil Service Commission held a total of 40 meetings during Fiscal Year 2002-2003. Of the 40 meetings, 20 were regular meetings and 20 were special meetings. Regular Commission meetings are on the first and third Mondays of each month in City Hall Hearing Room 400. When the regular meeting falls on a holiday, the Commission meets on the next succeeding business day unless it designates another day to meet at a prior regular meeting. Special meetings are called by the President or a majority of the Commission. All meetings of the Commission are open to the public except as otherwise legally authorized. -

Thomas J. Cahill Papers 1936-2002 SFH 15

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7489r8q8 No online items Finding Aid to the Thomas J. Cahill Papers 1936-2002 SFH 15 Larissa C. Brooks and Wendy Kramer San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library 2010 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA 94102 [email protected] URL: http://www.sfpl.org/sfhistory Finding Aid to the Thomas J. SFH 15 1 Cahill Papers 1936-2002 SFH 15 Title: Thomas J. Cahill Papers Date (inclusive): 1936-2002 Date (bulk): bulk Identifier/Call Number: SFH 15 Creator: Cahill, Thomas J. Physical Description: 7 cartons, 2 oversize flat boxes(10.7 Cubic Feet) Contributing Institution: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco, CA 94102 (415) 557-4567 [email protected] Abstract: Cahill's papers document his professional and public life from the 1940s-until his death in 2001, tracing the trajectory of his career as a San Francisco Police Department officer, homicide inspector, deputy chief of police, and chief of police; as well as his public life after he retired from SFPD, when he continued to be a prominent public figure and public speaker. The collection consists of police records, mainly from an undercover vice investigation from the 1950s; correspondence; scheduling diaries; speech materials; papers from conferences and events; certificates and awards; newspaper clippings and publications, the bulk of which feature or include Cahill; photographs, and audiorecordings. Physical Location: The collection is stored onsite. Language of Materials: Collection materials are in English. Access The collection is open for research. Photographs may be viewed during the San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection's open hours. -

"Jack" Shelley Collection, 1905-1974

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf558003vq No online items Inventory of the John Francis "Jack" Shelley Collection, 1905-1974 Processed by Leon Sompolinsky; machine-readable finding aid created by James Lake Labor Archives and Research Center San Francisco State University 480 Winston Drive San Francisco, California 94132 Phone: (415) 564-4010 Fax: (415) 564-3606 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.sfsu.edu/special/larc.html © 1999 San Francisco State University. All rights reserved. Inventory of the John Francis 1992/020 1 "Jack" Shelley Collection, 1905-1974 Inventory of the John Francis "Jack" Shelley Collection, 1905-1974 Accession number: 1992/020 Labor Archives & Research Center San Francisco State University San Francisco, California Contact Information: Labor Archives & Research Center San Francisco State University 480 Winston Drive San Francisco, California 94132 Phone: (415) 564-4010 Fax: (415) 564-3606 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.sfsu.edu/special/larc.html Processed by: Leon Sompolinsky Date Completed: 1993 Encoded by: James Lake © 1999 San Francisco State University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: John Francis "Jack" Shelley Collection, Date (inclusive): 1905-1974 Accession number: 1992/020 Creator: Shelley, John Francis Extent: 27 cubic feet Repository: San Francisco State University. Labor Archives & Research Center San Francisco, California 94132 Shelf location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Center's online catalog. Language: English. Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the Labor Archives & Research Center. All requests for permission to publish or quote from materials must be submitted in writing to the Director of the Archives. -

Download File

The “Total Campaign” How Ronald Reagan Overwhelmingly Won the California Gubernatorial Election of 1966 Senior Thesis by Kevin McKenna Department of History, Columbia University Professor William Leach, Advisor Professor Jefferson Decker, Second Reader Submitted April 12, 2010 Kevin McKenna Senior Thesis Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………3 The Political Landscape………………………………………………………………………….10 The Setting ……………………………………………………………………………….10 California Politics ………………………………………………………………………..12 The Candidate……...…………………………………………………………………………….19 Becoming Conservative………………………………………………………………….19 Deciding to Run ………………………………………………………………………….21 The Consultants……..…………………………………………………………………………...23 Political Campaigns Before 1966 ………………………………………………………..23 Stu Spencer and Bill Roberts …………………………………………………………….25 Rockefeller Campaign ……………………………………………………………………27 Educating Ronald Reagan ……………………………………………………………….28 Campaign Style …………………………………………………………………………..32 The Grassroots Activists..………………………………………………………………………..37 Conservatives Take Over the Party of Earl Warren ……………………………………..37 Grassroots Activism in the Reagan Campaign …………………………………………..40 Winning the Primary……………………………………………………………………………..45 The Eleventh Commandment …………………………………………………………….45 Challenging the Establishment …………………………………………………………..46 Getting Out the Vote for Reagan ………………………………………………………...49 -2- Kevin McKenna Senior Thesis Triumph: The General Election Campaign……………………………………………………...52 The Democratic Primary ………………………………………………………………...52 Framing the -

The Haight & the Hierarchy: Church

The Haight & the Hierarchy: Church, City, and Culture in San Francisco, 1967-2008 Sarah Anne Morris Dr. Thomas A. Tweed, Advisor Dr. Kathleen Sprows Cummings, Second Reader Department of American Studies University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, Indiana March 16, 2016 CONTENTS List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………………….………..ii Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………….………… iii Abstract…………..…………………………………………………………………………………….…..v Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Methods and Sources…………………………………………………………………………….. 6 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………….….… 8 Significance of the Project……………………………………………………………….….……11 1. 1967 | Unity: The Trial of Lenore Kandel’s “The Love Book”…………………..…………………15 Church and City Take on “The Love Book:” Institutions Join Forces…………..…………….…19 The Trial: Defending Catholic Clean Culture………………………………………………….…22 An Unnerving Future: Catholicism and the City after the Love Book Trial……………….…….27 2. 1987 | Tension: Pope John Paul II Visits the City………………………………………..….……… 29 Majority without Authority: The Church Adjusts to Its New Status…………………………..….30 Church and City Navigate New Waters: Episodic Discomfort………………………………….. 34 Task Force on Gay/Lesbian Issues & AIDS: Sustained Conflict………………………..…..……37 Preparing for the Pope: Diplomacy Amidst Anger……………………………………….……… 41 A City Holds Its Breath: Pope John Paul II Visits San Francisco……………………….………. 44 A Mixed Bag: San Francisco Catholics Reflect on a Symbolic Visit…………………………… 47 3. 2008 | Division: Proposition 8 Tears Church and City -

California State Government Project

Alarcon, Arthur L. Oral History Interview with Arthur L. Alarcon. Interviewed by Carlos Vasquez 1988 Language: English Project: California State Government Status: Completed; 394 pages Abstract Alarcon discusses his family background, education, experience in the military, post-secondary education, and activities, events, and issues during his tenure in the Edmund G. Brown, Sr., administration from 1961-1964, in particular those relating to narcotics, capital punishment, extradition, clemency, and law enforcement. Alquist, Alfred E. Oral History Interview with Alfred Alquist. Interviewed by Gabrielle Morris and Donald B. Seney 1987 Language: English Project: California State Government Status: Completed; 182 pages Abstract The interview discusses Democratic party politics in Santa Clara County as well as statewide. He speaks about his election campaigns from 1960 through 1984, including his candidacy for Lt. Governor in 1970. He also discusses issues such as campaign spending, reapportionment, economic development, and the budgetary process, as well as personalities such as Governor Edmund G. Brown, Sr., John Vasconcellos, and others. It also includes comments by Administrative Assistant Loretta Riddle on Alquist's San Jose office. Alshuler, Robert E. Oral History Interview with Robert E. Alshuler. Interviewed by Dale E. Treleven 1991 Language: English Project: California State Government Status: Completed; 157 pages Abstract Alshuler discusses his family background, education in Los Angeles and at UCLA, student activities leadership, presidency of the UCLA Alumni Association, and business of the Regents of the University of California during his ex officio regency from 1961 to 1963. Babbage, John D. Oral History Interview with John D. Babbage. Interviewed by Enid Hart Douglass 1987 Language: English Project: California State Government Status: Completed; 145 pages Abstract The interview includes biographical background information: family, education, training as a lawyer, and work for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (1941-1946).