Value Creation Drivers in a Secondary Buyout – The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Private Equity Confidence Survey Central Europe Winter 2018 This Publication Contains General Information Only

Caution returns Private Equity Confidence Survey Central Europe Winter 2018 This publication contains general information only. The publication has been prepared on the basis of information and forecasts in the public domain. None of the information on which the publication is based has been independently verified by Deloitte and none of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, any of its member firms or any of the foregoing’s affiliates (collectively the “Deloitte Network”) take any responsibility for the content thereof. No entity in the Deloitte Network nor any of their affiliates nor their respective members, directors, employees and agents accept any liability with respect to the accuracy or completeness, or in relation to the use by any recipient, of the information, projections or opinions contained in the publication and no entity in Deloitte Network shall be responsible for any loss whatsoever sustained by any person who relies thereon. Caution returns | Private Equity Confidence Survey Central Europe Introduction The Central European (CE) private equity (PE) market Croatia and Lithuania are all expected to grow at second fund on €21m, putting it well on its way to its may be reverting to its usual pace of activity following under 3.0%. €55m target after launching in January. A new fund a prolonged period of large exits and fundraisings as has been launched for the Baltics, with Lithuanian well as strong levels of deal-doing. While we remain Exit activity continues apace, with the headline-hitting asset manager Invalda INVL seeking €200m for its confident conditions remain conducive to transacting, homeruns of 2017 giving way to a steadier flow of INVL Baltic Sea Growth Fund to back Baltic businesses respondents are hinting at some caution as we enter mid-market exits dominated by local players. -

BC Partners London Paris Milan Hamburg Geneva New York AGENDA

GREECE: The Ne w Reform Agenda Investment & Business Opportunities in Greece A Global Investor’s Perspective Nikos Stathopoulos 30th October, 2008 New York City BC Partners London Paris Milan Hamburg Geneva New York AGENDA Greece as an investment destination Case Studies Conclusions BC Partners London Paris Milan Hamburg Geneva New York Private Equity is a Major Player in European M&A European LBO Activity as a % of all European M&A value 2007 BC Partners London Paris Milan Hamburg Geneva New York BC Partners: a Leading Global Private Equity Fund – 1 BC Funds Investments by Sector Investment in 67 companies since foundation in 1986 ̶ Total transaction value of US$100bn Automotive Health 6% Retail ̶ Invested in 13 countries in Europe, US and Asia 8% 23% ̶ Current portfolio companies representing an aggregate turnover Media/Telecom of US$30bn and employing 81,000 employees 11% Service Consumer 14% goods Over US$17bn ra ise d in e ig ht f un ds 19% ̶ Fund VIII with US$9.3bn of equity Industry 19% ̶ Up to US$2.4bn equity for single transaction available plus International Presence additional equity from BC funds co-investors ̶ Average transaction value of investments of US$3.1bn since 2000 New York/ (from US$141m to US$29.9bn) London London Presence in Europe and the US Hamburg ̶ Offices in London, Paris, Milan, Geneva, Hamburg, and New York Paris ̶ 50 investment professionals with broad individual experience Geneva Milan BC Partners London Paris Milan Hamburg Geneva New York BC Partners: a Leading Global Private Equity Fund – 2 Selected -

Npes Booklet FINAL.Pdf

Nordic private Equity Summit June 18th 2015 - Copenhagen, Denmark PREFATORY NOTE Welcome to the 2015 Nordic Private Equity Summit! We would like to welcome each of you to the first Nordic Private Equity Summit. When we planned the conference we looked into the super trends of the private equity industry and built the programme accordingly with speakers, panelists and discussion topics to capture these key trends. The result is an outstanding programme presented to you in this booklet. This Summit brings together a variety of high-level General Partners, Limited Partners and CEOs from all over the private equity community. And we hope you will enjoy the day and help us start a tradition for providing the best networking opportunities and the best speakers at the Nordic Private Equity Summit in Copenhagen. Best wishes, Ole Steen Andersen Jannick Nytoft Chairman, DVCA CEO, DVCA NPES Moderator 2015 WiFi access Joachim Sperling WiFi Axcel Network: Guest Username: kursus1 Password: eykursus1 Nordic private Equity Summit CONTENT AGENDA 8 FLOOR PLAN 10 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS 23 STATUS ON PE IN DENMARK DVCA Annual Report 2014 - 2015 27 BREAKOUT SESSIONS PE Trends Towards 2020 31 Funding for Growth Companies in Denmark 36 Business Development in Venture-owned Companies 40 Leverage in Buyouts - Market Trends 45 Specialization in PE - Yet to be Seen? 50 Life-Science: The Untold Success Story 55 PANEL Our Look on PE Ownership 59 © 2015 Ernst & Young P/S. All Rights Reserved. A15023 Your success story. Plot provided by EY. Our Transaction Advisory Services team understands the importance of managing your capital agenda, from strategy to success. -

Entrepreneurship in Spain

All you need to know about entrepreneurship in Spain June 2021 edition A way to make Europe EUROPEAN REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT1 FUND CONTENT Part I – STARTING POINT • Creating a startup Part II – RESOURCES FOR STARTUPS • Resources for startups • Incubators • Accelerators • Specific services suppliers Part III – FINANCING FOR STARTUPS • How to obtain financing • Private sector • Public sector • European calls • National calls Part IV – EVENTS FOR STARTUPS • Events Part V – AUTONOMOUS REGIONS • Programs and subsidies for startups This guide is intended as a collection of resources for startups in their different stages of seeking public and/or private funding 2 Part I Starting point CREATING A STARTUP IN SPAIN The steps to establish a startup are the same as for any other company. The very first one is to determine the most appropriate legal form, a decision that will be influenced by the startup´s later needs regarding participation deals and receipt of third-party investment. The most used legal forms are: Spain • Limited Liability Company (Sociedad Limitada, S.L.) in • Corporation (Sociedad Anónima, S.A.). startup Both forms can also be set up as a sole-shareholder entity (Sociedad Anónima Unipersonal, S.A.U. and Sociedad Limitada Unipersonal, S.L.U. respectively) a at the time of incorporation or be converted into a sole-shareholder entity afterwards. While there are alternatives to these legal forms, they aren´t advisable for startups that will be seeking to add partners to the project and/or third-party investors. For information purposes, these include: Freelancer (Autónomo), Private partnership (Sociedad Civil) or Jointly-Owned Entity (Comunidad de creating Bienes), or a Cooperative (Cooperativa). -

Welcome to the 12Th Annual INSEAD Private Equity Conference

Welcome to the 12th Annual INSEAD Private Equity Conference INSEAD welcomes you to the 12th Annual Private Equity Conference. The conference, inaugurated in 2003, has become the most successful private equity and venture capital event hosted by a European academic institution. With over 1,500 alumni working in the industry worldwide, INSEAD’s presence in the private equity community is well-recognized. This conference is a gathering amongst leading practitioners, academics and the INSEAD community to debate the forces shaping the private equity industry. We are delighted to host an impressive and diverse group of experienced industry professionals here on INSEAD Europe Campus. Since the financial crisis, one of the strongest trends in private equity has been increased focus on value creation. This year’s theme, “How to achieve alpha in the current environment,” aims to delve into the topic of generating returns through operational change, and assess the implications of this trend for the future of private equity. Our keynote speakers, leveraged buyouts and operational excellence panels will explore the topic of value creation deeper. Beyond value creation, the industry is further being shaped by a number of different dynamics and intense competition. To further develop the main theme, we have lined up a focused range of panels and have assembled a diverse group of outstanding panelists and moderators for you. Our panels will attempt to give an update on the current state in different parts of the industry, such as distressed investing, infrastructure and real assets, emerging strategies and limited partner relationships. The annual conference is organized by student and alumni members of the INSEAD Private Equity Club, Global Private Equity Initiative (INSEAD faculty body focused on research in Private Equity industry), Alumni Relations and Student Life offices. -

ESG in Private Equity: a Fast-Evolving Standard

ESG in Private Equity: A Fast-Evolving Standard ESG in Private Equity: A Fast-Evolving Standard This report was published by INSEAD’s Global Private Equity Initiative (GPEI). It was written by Bowen White, Research Associate at the GPEI, under the supervision of Claudia Zeisberger, Academic Director of the GPEI and Professor of Decision Sciences and Entrepreneurship and Family Enterprises at INSEAD, and Michael Prahl, Executive Director of the GPEI. We would like to thank the GPs participating in our report for their availability, candor and engagement. We would also like to thank Hazel Hamelin, senior editor at INSEAD, for her invaluable support. The GPEI looks to partner with stakeholders in the private equity industry to collaborate on research ideas and projects. Its core supporters are: GPEI welcomes private equity investors interested in the center’s research efforts to reach out to us in Europe or Singapore. For further information on INSEAD’s Global Private Equity Initiative, please visit www.insead.edu/gpei. 1 ESG in Private Equity: A Fast-Evolving Standard Contents Overview and Findings 3 General Partner Snapshots 9 The Abraaj Group ACTIS Apax Partners BC Partners The Carlyle Group Doughty Hanson KKR Partners Group Permira Standard Chartered Bank Terra Firma Capital Partners Summary Comments 42 Appendix A 43 Further Reading 44 May 2014 2 ESG in Private Equity: A Fast-Evolving Standard Overview The ability of private equity firms to manage environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment considerations in their portfolio companies has received increased attention of late. Private equity firms on the fundraising trail are not the only GPs1 cognizant of this trend; cost-savings potential, competitor activity and regulation all contribute to the rising awareness of ESG factors in investment committee decision-making.2 The focus on ESG considerations has developed alongside investors’ growing appreciation of the impact that nonfinancial factors can have on value creation, long-term company performance, and the health of society at large. -

ILPA Releases Second Report in Diversity in Action Series

ILPA Releases Second Report in Diversity in Action Series Diversity in Action – Sharing Our Progress Report Details the Initiative’s Growth and Insights Into Integrating DEI Into Investment Strategies 1776 Eye St. NW August 31, 2021 (Washington, D.C.) The Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA) today released the Suite 525 second report in its Diversity in Action – Sharing Our Progress series. The report series is an extension of ILPA’s Washington, DC Diversity in Action initiative and aims to provide actionable recommendations on steps that can be taken to 20006 improve diversity, equity and inclusion in private markets. “The industry continues to respond positively to the Diversity in Action Initiative with new signatories joining every week,” said Steve Nelson, CEO of ILPA. “The Initiative now claims 180 signatories who have all been incredibly active in conversations with one another and have acted as tremendous partners to ILPA on our related work, having meaningfully contributed to our updated ILPA Diversity Metrics Template.” The Diversity in Action – Sharing Our Progress report series tracks the evolution of Initiative signatories by geography, strategy and fund size as well as progress on adoption of all the actions within the Framework. As of August 2021, the Initiative’s geographic reach is increasing, now with 38 signatories outside North America, a 52% increase in this cohort since April. The latest report focuses on how signatories are integrating diversity, equity and inclusion into investment strategies including -

Canadian Private Equity Buyout Review

Canadian Private Equity Buyout Review Full Year 2018 Ben Nelms, Reuters Table of Contents Canada’s PE Buyout Market in 2018 3 $ Invested and # Companies Financed 5 Investment by Company Location 7 Investment by Transaction Type 8 Investment by Investor Location 9 PE Investment vs. all Canadian M&A 10 Top PE Buyout Deals 11 Investment by Deal Size 12 Investment by Company Sector 13 Canadian Firms’ Investment Abroad 14 Buyout Funds Raised 16 PE Buyout-Backed Exits 17 PE Buyout Returns 18 Explanatory Notes & Contacts 19 2 Canadian Private Equity Buyout Market Activity: Full Year 2018 Canadian Buyout-PE Market Trends Canada saw a record-breaking year of investment from buyout and related private equity investors in 2018, with 345 transactions collectively valued at $37.2 billion. Collective deal values for the year smashed the previous record set in 2007, when Canadian companies received $33.7 billion in investment. Deal volumes, however, were down 10% from the year prior, indicating more investment dollars flowing into fewer deals. The $5.0 billion secondary sale of Bolton, Ontario-based Husky Injection Moldings Systems by OMERS Private Equity and Berkshire Hathaway to U.S. private equity firm Platinum Equity, has retained the number one spot in both Canada’s top deals list and top exits list. Ranking second and third on the list were Enbridge’s natural gas gathering and processing business, and Enercare, both having been acquired by Brookfield Asset Management for $4.3 billion apiece. Canadian Market Trends by Sector & Stage The Information Technology & Media sector remained the most active throughout the year, with 54 deals collectively valued at $3.9 billion. -

NB Private Equity Partners Investor Presentation November 2020 THIS PRESENTATION CONTAINS FORWARD LOOKING STATEMENTS

NB Private Equity Partners Investor Presentation November 2020 THIS PRESENTATION CONTAINS FORWARD LOOKING STATEMENTS THIS PRESENTATION HAS BEEN CREATED WITH THE BEST AVAILABLE INFORMATION AT THIS TIME. INFORMATION FLOW IN THE PRIVATE EQUITY ASSET CLASS OFTEN LAGS FOR SEVERAL MONTHS. THE PRESENTATION CONTAINS A LARGE AMOUNT OF FORWARD LOOKING STATEMENTS, PROJECTIONS AND PRO FORMA INFORMATION BASED UPON THAT AVAILABLE INFORMATION. THERE CAN BE NO ASSURANCE THAT THOSE STATEMENTS, PROJECTIONS AND PRO FORMA NUMBERS WILL BE CORRECT; ALL OF THEM ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE AS THE UNDERLYING INFORMATION DEVELOPS. THE INFORMATION IN THIS PRESENTATION IS PRIMARILY BASED ON THE 31 AUGUST 2020 MONTHLY ESTIMATE IN WHICH 86% OF THE PRIVATE EQUITY FAIR VALUE IS BASED ON 30 JUNE 2020 PRIVATE VALUATION INFORMATION, AND 14% IS BASED ON 31 AUGUST 2020 VALUATION INFORMATION (6% IN PUBLIC SECURITIES AND 8% IN ROLLED FORWARD DEBT POSITIONS). THE 30 SEPTEMBER 2020 NBPE ESTIMATED MONTHLY NAV UPDATE WHICH WAS PUBLISHED ON 15 OCTOBER 2020 CONTAINED ONLY 14% OF VALUATION INFORMATION AS OF Q3 2020. AS A RESULT THE SEPTEMBER MONTHLY NAV UPDATE IS NOT DIRECTLY COMPARABLE TO PRIOR YEAR FIGURES WHICH HAVE BEEN UPDATED WITH FULL QUARTERLY INFORMATION. THE MAJORITY OF THIS PRESENTATION REMAINS BASED ON 31 AUGUST 2020 VALUATIONS. 2 NB Private Markets Overview An Industry Leader With An Attractive Track Record • 30+ years as a private market investor Co-investments $19 bn(1) Primaries $26 bn(1) • Committed ~$10 billion annually to private markets over the past 3 years Over $90 Secondaries • Unique position in the private market (1) Billion $12 bn ecosystem • A recognized private equity manager within Direct Private Credit the industry $6 bn Direct Specialty Strategies $7 bn GP Manager Stakes $22 bn _______________________ Note: As of June 30, 2020. -

TPG the Blackstone Group Kohlberg Kravis Roberts Goldman Sachs

TPG Themay 2012 Blackstone Group Kohlbergprivate equity international Kravis Roberts Goldman page 37 Sachs Principal Investment Area The Carlyle Group CVC Capital Partners Apax Partners Apollo Global Management Bain Capital Oaktree Capital Management Hellman & Friedman General Atlantic Providence Equity Partners Cerberus Capital Management Warburg Pincus Advent International First Reserve Corporation Silver Lake Lone Star Funds Riverstone Holdings Leonard Green & Partners Thomas H. Lee Partners Golden Gate Capital BC Partners JC Flowers & Co. Terra Firma Capital Partners American Capital Teachers’ Private Capital NGP Energy Capital Management Fortress Investment Group Clayton Dubilier & Rice CPP Investment Board Bridgepoint PAI Partners AXA Private Equity Mount Kellett Capital EQT Partners Marfin Investment Group EnCap Investments Abraaj Capital Citi Capital Advisors Onex International Petroleum Investment Company Stone Point Capital TA Associates Hony Capital Nordic Capital ArcLight Capital Partners Equistone Partners Europe CDH Investments HitecVision AS JP Morgan Asset Management Charterhouse Capital Partners American Securities Capital Partners Mubadala Development Company Summit Partners Tiger Global Management Avista Capital Partners AlpInvest Partners Dubai International Capital MatlinPatterson Global Advisers GI Partners New Mountain Capital Kelso & Co. Denham Capital Management Sun Capital Partners Ares Management Lion Capital Investcorp Bank BSC Lindsay Goldberg Pamplona Capital Management H.I.G. Capital Doughty Hanson Accel Partners Berkshire Partners Vista Equity Partners WL Ross & Co. Welsh Carson Anderson & Stowe Centerbridge Capital Partners Energy Capital Partners Intermediate Capital Group Cinven Oak Hill Capital Partners page 40 private equity international may 2012 pei 300 TPG still top of the class It’s a second consecutive year at the top in Indonesian manager Northstar Pacific for TPG, whose remarkable fundraising (as it looks to get a foot in the door of machine accumulated a cool $49.9 bil- another high-potential emerging market). -

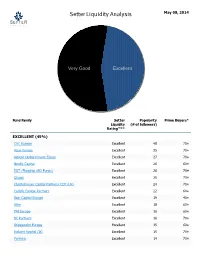

Setter Liquidity Analysis S E T T E R C a P I T a L

May 08, 2014 Setter Liquidity Analysis S E T T E R C A P I T A L Very Good Excellent Fund Family Setter Popularity Prime Buyers* Liquidity (# of followers) Rating™** EXCELLENT (45%) CVC Europe Excellent 40 70+ Apax Europe Excellent 35 70+ Advent Global Private Equity Excellent 27 70+ Nordic Capital Excellent 26 60+ EQT (Flagship LBO Funds) Excellent 26 70+ Cinven Excellent 25 70+ Charterhouse Capital Partners CCP (UK) Excellent 24 70+ Carlyle Europe Partners Excellent 22 60+ Bain Capital Europe Excellent 19 40+ Altor Excellent 18 60+ PAI Europe Excellent 16 60+ BC Partners Excellent 16 70+ Bridgepoint Europe Excellent 15 60+ Industri Kapital (IK) Excellent 15 70+ Permira Excellent 14 70+ HgCapital(LBO) Excellent 13 50+ HgCapital(LBO) Excellent 13 50+ Graphite Capital Excellent 8 40+ KKR Europe Excellent 8 40+ VERY GOOD (55%) 3i Buyouts / Eurofund Very Good 15 40+ HitecVision Very Good 12 20+ Triton Very Good 10 30+ Montagu Private Equity Very Good 9 30+ Alpha Private Equity Very Good 7 30+ Segulah Management Very Good 7 40+ Doughty Hanson (LBO) Very Good 6 30+ Herkules Very Good 6 20+ Axcel Very Good 6 30+ Accent Equity Partners Very Good 6 20+ Egeria Very Good 5 20+ Sovereign Capital Very Good 5 30+ Astorg Partners Very Good 5 20+ Investindustrial Very Good 4 30+ Apax France Very Good 4 20+ Phoenix Equity Very Good 4 20+ TDR Capital Very Good 4 30+ Riverside Europe Very Good 4 30+ Gilde Buy Out Partners Very Good 4 20+ Chequers Capital Very Good 3 30+ Exponent Private Equity Partners Very Good 3 30+ Capiton Europe Very Good 2 20+ * Prime Buyers are buyers that are existing investors in the fund family, have it on their shortlist and/or have recently priced. -

Fundraising Report H1 2020

FUNDRAISING REPORT H1 2020 Private Equity International's interactive and downloadable review of H1 2020's fundraising environment Download data Carmela Mendoza Daniel Humphrey Rodriguez Isobel Markham Private Equity International Head of Fund Manager Research Private Equity International [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Fundraising overview Half-year fundraising Private equity firms raised $241 billion in the 600 1,200 six months to June, in line with the two 550 1,100 previous years. 500 1,000 450 900 Despite coronavirus disruption, preliminary 400 800 figures from PEI data show capital raising for ) d n e b 350 700 H1 2020, which includes only final and s $ ( o l c d e interim closes, was up $7.3 billion from the 300 600 s s d i n a r u l equivalent period last year. f a 250 500 f t i o p o a N C 200 400 The average fund size was $715 million as of end-June, the highest since 2015 and 26 150 300 percent larger than the previous year's $566 100 200 million. 50 100 0 0 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 H1 ($bn) H2 ($bn) Number of funds closed FUNDRAISING REPORT Download data H1 2020 > Fundraising overview Largest funds closed in H1 2020 The 10 largest fund closes in H1 2020 saw Ardian Secondary Fund VIII (AS… 14 managers collect $78.2 billion between Lexington Capital Partners IX 14 them, roughly the same amount raised by the 10 largest funds in the same period last Insight Venture Partners XI 9.5 year.