Madeline Earp Asia Research Associate Committee to Protect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prémio Sakharov Para a Liberdade De Pensamento

PRÉMIO SAKHAROV PARA A LIBERDADE DE PENSAMENTO uma edição: www.carloscoelho.eu por Carlos Coelho Deputado ao Parlamento Europeu, Membro da Comissão das Liberdades Cívicas, Justiça e Assuntos Internos PRÉMIO SAKHAROV PARA A LIBERDADE DE PENSAMENTO Nesta pequena edição divulgo o Prémio Sakharov que é um dos instrumentos da União Europeia para promover os Direitos do Homem no Mundo. O Prémio Sakharov recompensa personalidades excepcio- nais que lutam contra a intolerância, o fanatismo e a opres- são. A exemplo de Andrei Sakharov, os laureados com este Pré- mio são ou foram exemplos da coragem que é necessária para defender os Direitos do Homem e a Liberdade de ex- pressão. 2 3 E QUEM FOI ANDREI SAKHAROV? Prémio Nobel da Paz em 1975, o físico russo Andrei Dmitrievitch Sakharov (1921-1989) foi, antes de mais, o inventor da bomba de hidrogénio. O QUE É Preocupado com as consequências dos seus trabalhos para o futuro da humanidade, O PRÉMIO SAKHAROV? procurou despertar a consciência do perigo da corrida ao armamento nuclear. Obteve um êxito parcial com a assinatura do Tratado O “Prémio Sakharov para a Liberdade de Pensamento” é contra os Ensaios Nucleares em 1963. atribuído todos os anos pelo Parlamento Europeu. Criado em 1988, reconhece e distingue personalidades ou entidades Considerado na URSS como um dissidente que se esforçam por defender os Direitos Humanos e as com ideias subversivas, cria, nos anos setenta, liberdades fundamentais. um Comité para a defesa dos direitos do Homem e para a defesa das vítimas políticas. No dia 10 de Dezembro (ou na data mais próxima), o Os seus esforços viriam a ser coroados com o Parlamento Europeu entrega o seu Prémio no valor de Prémio Nobel da Paz em 1975. -

SAKHAROV PRIZE NETWORK NEWSLETTER 10/2015 Raif Badawi Is the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought's Newest Laureate 29/10/2015

SAKHAROV PRIZE NETWORK NEWSLETTER 10/2015 Raif Badawi is the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought's newest laureate 29/10/2015 the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought for 2015 has been awarded to Saudi blogger Raif Badawi. EP President Schulz called Badawi ‘a hero in our modern internet world who is fighting for democracy and facing real torture’ as he announced the decision taken by the Conference of Presidents. ‘I have asked the King of Saudi Arabia to pardon Badawi and release him to give him the chance to receive the Sakharov Prize here in the European Parliament’, the EP President and Sakharov Prize Network co-chair said. Badawi was shortlisted as a finalist for the Prize together with the Democratic Opposition in Venezuela and murdered Russian opposition politician and activist Boris Nemtsov by a vote of the Foreign Affairs and Development Committees. The initial list of nominees included also Edna Adan Ismail, Nadiya Savchenko, and Edward Snowden, Antoine Deltour and Stéphanie Gibaud. Link: President Schulz press point Flogging of Raif Badawi to resume, wife warns 27/10/2015: Ensaf Haidair, the wife of Saudi blogger, 2015 SP laureate, Raif Badawi, said she has been informed that the Saudi authorities have given the green light to the resumption of her husband's flogging. In a statement published on the Raif Badawi Foundation website, Haidar said that she received her information from the same source who had warned her about Badawi’s pending flogging at the beginning of January 2015, a few days before Badawi was flogged. Link: Fondation Raif Badawi Xanana Gusmao and DEVE Delegation at Milan EXPO on Feeding the Planet 15/10/2015: 1999 Sakharov Prize laureate and first President of Timor-Leste, Xanana Gusmão, and a delegation of the EP’s DEVE Committee led by Chairwoman and SPN Member Linda McAvan tackled the right to food, land rights and the use of research for the effective realisation of the Sustainable Development Goals during an intensive two day-programme in Milan. -

What Is Your Assessment of the Effect Which Preparations for the Olympics

Reporters Without Borders USA 1500 K Street, NW, Suite 600 Washington DC 20005 Tel: 202 256-5613 Email: [email protected] Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic & Security Review Commission by Lucie Morillon, Washington Director, Reporters Without Borders Hearing on “Access to Information and Media Control in the People’s Republic of China” Panel on “Information Control and Media Influence Associated to the Olympics” June 18, 2008 1 - What is your assessment of the effect that preparations for the Olympics have had on press freedom and access to information in the PRC? The Olympic Games have focused the world’s and the media’s, attention on China. They have forced Chinese authorities to communicate more and to be more media-conscious. They are becoming more responsive to news events, and quicker to put their spin on what the media reports. In the run-up to the Olympic Games, more journalists are becoming interested in China, and they have more resources at their disposal to cover the situation in the country. As a result, more information is being released. But this mainly holds true for the foreign media and their public, not so much the Chinese public. For example, Xinhua, the state news agency, is releasing an increasing number of stories ionly in English about previously taboo topics, such as peasants riots, in a clear attempt to show the rest of the world that China is opening up, while keeping this information out of reach of most Chinese citizens. Accelerating the process of opening up China to information was one of the arguments used for awarding the Games to Beijing. -

Human Rights and Democracy: the 2014 Foreign & Hrdreport.Fco.Gov.Uk Commonwealth Office Report

Human Rights and Democracy: The 2014 Foreign & hrdreport.fco.gov.uk Commonwealth Office Report Human Rights and Democracy: The 2014 Foreign & Commonwealth Office Report 1 Human Rights and Democracy: The 2014 Foreign & Commonwealth Office Report Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs by Command of Her Majesty March 2015 Cm 9027 2 Human Rights and Democracy: The 2014 Foreign & Commonwealth Office Report © Crown copyright 2015 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at: Communications Team, Human Rights and Democracy Department, Room WH.1.203, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, King Charles Street, London, SW1A 2AH Print ISBN 9781474114875 Web ISBN 9781474114882 ID P002702621 03/15 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Cover: Iraqi Yezidis flee to surrounding mountains across the border into Turkey Photo: Huseyin Bagis/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images Contents 3 Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................... 8 Foreword by Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond .......................................10 Foreword by Minister for Human Rights Baroness Anelay .........................12 CHAPTER I: Protecting Civil Society Space and Human Rights Defenders ..15 The Current State of Civil Society Space ................................................................................ -

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

Hujintao060927letter

September 29, 2006 President Hu Jintao People's Republic of China Zhongnanhai, Xichengqu, Beijing People's Republic of China Dear President Hu, We, the undersigned human rights advocates, lawyers, and scholars, write to urge your commitment to ensuring the civil rights of advocates for social justice. We note with concern the sharp increase in official retaliation against such advocates and their families through persistent harassment, banishment, detention, arrest, and imprisonment. We note, too, the frequent use of state secrets charges to discourage social activism. For the international community to take seriously China’s oft-stated commitment to a rule of law, and for China’s own citizens to trust the judicial system to redress legitimate grievances, it is urgent that China’s central leadership not look the other way when local courts and law enforcement officials ignore China’s laws and legal procedures with impunity. It is equally urgent that judicial authorities throughout China cease to use China’s state secrets laws to prevent defendants in politically sensitive cases from exercising their rights to fair and impartial hearings. Several recent cases cast doubt on your government’s willingness to take those principled steps. Four such cases are of particular concern, those of rights defenders Gao Zhisheng, a lawyer, Chen Guangcheng, a legal activist, Zhao Yan, a journalist, and Hu Jia, a grassroots HIV/AIDS activist. Their apprehension, the charges against Messrs. Gao, Chen, and Zhao, Mr. Chen’s and Mr. Zhao’s subsequent trials and sentencing, and Mr. Hu’s forcible removal to a police station without a warrant are representative of China’s legal system at its worst. -

Sakharov's Legacy on the Centenary of His Birth

AT A GLANCE Sakharov's legacy on the centenary of his birth Andrey Sakharov was a Soviet physicist who played a leading role in his country's nuclear weapons programme. However, in the 1960s he fell out of favour with the regime due to his activism for disarmament and human rights. On the 100th anniversary of his birth, Sakharov's legacy is more relevant than ever. Since 1988, the European Parliament has awarded an annual prize for freedom of thought named after him. Andrey Sakharov: Scientist, disarmament campaigner, human rights defender Born on 21 May 1921 in Moscow, Andrey Sakharov was a physicist who in 1948 joined the Soviet atomic programme, where he played a leading role in work that led to the country's first successful test of an atomic bomb in 1949. In the 1950s, Sakharov helped to develop the first Soviet hydrogen bomb and the Tsar Bomba, the largest atomic bomb ever exploded. However, by the late 1950s Sakharov was becoming increasingly concerned about the dangers of these new weapons; together with other nuclear scientists, he persuaded the Soviet authorities to sign a partial test ban treaty with the US and UK in 1963, prohibiting atmospheric and underwater nuclear tests. Sakharov's opposition to antiballistic missile defences, which he felt would increase the risk of nuclear war, eventually put him at loggerheads with the Soviet regime. In 1968, Sakharov wrote his 'Reflections on Progress, Peaceful Co-Existence, and Intellectual Freedom', warning of the dangers of nuclear weapons and criticising the repression of dissidents. The essay was never published in the Soviet Union, but typewritten copies circulated widely and reached Western media. -

CECC China Human Rights and Rule of Law Update Found on the CLB Web Site and in the CECC Political Prisoner Data Base

China Human Rights and October 1, 2005 Rule of Law Update Subscribe United States Congressional-Executive Commission on China Senator Chuck Hagel, Chairman | Representative Jim Leach, Co-Chairman Events Roundtable: China's Household Registration (Hukou) System: Discrimination and Reform The Congressional-Executive Commission on China held another in its series of staff-led Issues Roundtables, entitled China's Household Registration (Hukou) System: Discrimination and Reform, on September 2, from 2:00 - 3:30 PM in Room 2168 of the Rayburn House Office Building. The panelists were Fei-Ling Wang, Professor, The Sam Nunn School of International Affairs, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia; and Chloé Froissart, PhD candidate at the Institute of Political Science of Paris, affiliated to the Center for International Studies and Research, Paris; Research Fellow at the French Center for Research on Contemporary China, Hong Kong. Translation: Court Judgment in Shi Tao State Secrets Trial The Congressional-Executive Commission on China has prepared a translation of the Changsha Intermediate People's Court's Written Judgment in the Shi Tao State Secrets Trial. Translation: New Rules on Internet News Publishing The Congressional-Executive Commission on China has prepared a translation of the Rules on the Administration of Internet News Information Services, promulgated by the State Council Information Office and the Ministry of Information Industry on September 25, 2005. A summary of the Rules prepared by the Commission is available here. Updates on Rights and Law in China Human Rights Updates Rule of Law Updates All Updates Yahoo! Cited in Court Decision as Providing Evidence in Shi Tao State Secrets Trial On April 27, 2005, a Chinese court sentenced newspaper editor Shi Tao to 10 years imprisonment for disclosing state secrets for e-mailing notes of an editorial meeting to an organization in New York City. -

Arrest of Chinese Dissident Hu Jia

C 41 E/82 Official Journal of the European Union EN 19.2.2009 Thursday 17 January 2008 Arrest of Chinese dissident Hu Jia P6_TA(2008)0021 European Parliament resolution of 17 January 2008 on the arrest of the Chinese dissident Hu Jia (2009/C 41 E/11) The European Parliament, — having regard to its previous resolutions on the human rights situation in China, — having regard to the two latest rounds of the EU-China Dialogue on Human Rights held in Beijing on 17 October 2007, and in Berlin on 15 and 16 May 2007, — having regard to the public hearing held on 26 November 2007 by its Subcommittee on Human Rights concerning Human Rights in China in the run-up to the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, — having regard to the Olympic Truce called for by the UN General Assembly on 31 October 2007, when it urged UN Member States to observe and promote peace during the 2008 Olympic Games, — having regard to Rule 115(5) of its Rules of Procedure, A. whereas the human rights campaigner Hu Jia was taken away from his home in Beijing by police officers on 27 December 2007 on charges of inciting subversion, B. whereas Hu Jia and his wife, Zeng Jinyan, have thrown the spotlight on human rights abuses in China over the past few years and spent many periods under house arrest as a result of their campaigning, C. whereas Hu Jia is in bad health, suffering from a liver disease for which he must take medication, D. whereas in 2006 Time Magazine named Zeng Jinyan one of the world's one hundred heroes and pioneers and in 2007, together with Hu Jia, she received the Reporters without Borders special ‘China’ prize, and was nominated for the Sakharov Prize, E. -

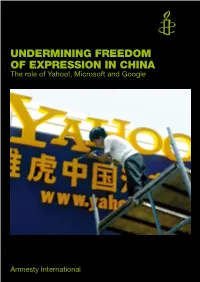

Undermining Freedom of Expression in China the Role of Yahoo!, Microsoft and Google

UNDERMINING FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN CHINA The role of Yahoo!, Microsoft and Google Amnesty International ‘And of course, the information society’s very life blood is freedom. It is freedom that enables citizens everywhere to benefit from knowledge, journalists to do their essential work, and citizens to hold government accountable. Without openness, without the right to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers, the information revolution will stall, and the information society we hope to build will be stillborn.’ KofiA nnan, UN Secretary General Published in July 2006 by Amnesty International UK The Human Rights Action Centre 17-25 New Inn Yard London EC2A 3EA United Kingdom www.amnesty.org.uk ISBN: 187332866 4 ISBN: 978-1-873328-66-8 AI Index: POL 30/026/2006 £5.99 CONTENTS Executive summary 4 1. Freedom of expression 8 1.1 A fundamental human right 8 1.2 Internet governance and human rights 8 2. Human rights responsibilities of companies 10 2.1 Responsibilities of Internet hardware and software companies 11 3. The human rights situation in China: an overview 13 3.1 The crackdown on human rights defenders 13 3.2 Curtailment of freedom of expression 14 3.3 Internet censorship in China 16 4. The role of Yahoo!, Microsoft and Google 17 4.1 Mismatch between values and actions 17 4.2 Contravening their principle that users come first 23 4.3 Uncovering their defences 23 4.4 From denial to acknowledgement 26 5. Recommendations for action 28 EXEcutIVE SuMMARY Amnesty International has produced many reports documenting the Chinese government’s violations of human rights.1 The expansion of investment in China by foreign companies in the field of information and communications technology puts them at risk of contributing to certain types of violation, particularly those relating to freedom of expression and the suppression of dissent. -

Sars Vs Aids

A TALE OF TWO CRISES: SARS VS AIDS BY HU JIA In this report, sent to HRIC and posted on a number of Chinese Web sites, Beijing Aizhixing Institute director Hu Jia provides a glimpse into the efforts and frustrations of a domestic NGO dedicated to addressing China’s AIDS tragedy, and to keeping the outside world informed of the true situation. On May 15, the date of the International AIDS Candlelight Memorial, China’s Vice Premier and Minister of Health,Wu Yi, met with World Health Organization Director-General Dr. Gro Harlem Brundtland in Geneva to outline the Chinese govern- ment’s efforts in controlling the SARS epidemic. On that same day,a team of WHO experts observed SARS prevention meas- ures in AIDS-stricken villages in Henan Province’s Shangcai County.Tonight by the light of a candle I record how local offi- cials made every effort to ensure that the truth was concealed from the visiting WHO experts. Beginning on May 15 a number of residents of Shangcai County’s AIDS-affected villages contacted me and reported unusual activities suggesting the imminent arrival of a VIP delegation. On May 16 news circulated from the local health department that a delegation from WHO and China’s Ministry Hu Jia tries to comfort Chen Yue, an AIDS-stricken mother. of Health would be visiting Shangcai County to observe what Photo courtesy of Open Magazine. measures were being taken to prevent the spread of SARS. During the day on May 17 portions of Shangcai County Over the previous two months Chinese officials had hindered were placed under curfew while local officials had village WHO efforts by providing falsified information. -

People's Republic of China the Olympics Countdown

China: The Olympics Countdown 1 People’s Republic of China The Olympics countdown – crackdown on activists threatens Olympics legacy Introduction With little more than four months to go before the Beijing Olympics, few substantial reforms have been introduced that will have a significant, positive impact on human rights in China.1 This is particularly apparent in the plight of individual activists and journalists, who have bravely sought to expose ongoing human rights abuses and call on the government to address them. Recent measures taken by the authorities to detain, prosecute and imprison those who raise human rights concerns suggest that, to date, the Olympic Games has failed to act as a catalyst for reform. Unless the Chinese authorities take steps to redress the situation urgently, a positive human rights legacy for the Beijing Olympics looks increasingly beyond reach. It is increasingly clear that much of the current wave of repression is occurring not in spite of the Olympics, but actually because of the Olympics. Peaceful human rights activists, and others who have publicly criticised official government policy, have been targeted in the official pre-Olympics ‘clean up’, in an apparent attempt to portray a ‘stable’ or ‘harmonious’ image to the world by August 2008. Recent official assertions of a ‘terrorist’ plot to attack the Olympic Games have given prominence to potential security threats to the Olympics, but a failure to back up such assertions with concrete evidence increases suspicions that the authorities are overstating such threats in an attempt to justify the current crackdown. Several peaceful activists, including those profiled in this series of reports, remain imprisoned or held under tight police surveillance.