The Brickmakers' Strikes on the Ganges Canal in 1848–

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uttarakhand Covid-19 Telephone/Mobile Directory Note

Uttarakhand Covid-19 Telephone/Mobile Directory Note: [email protected] https://health.uk.gov.in/pages/display/140-novel-corona-virus-guidelines-and-advisory- Sample Collection Centres https://covid19.uk.gov.in/map/sccLocation.aspx Availability of Beds https://covid19.uk.gov.in/bedssummary.aspx Covid-19 Vaccination Sites www.cowin.gov.in RT PCR Testing Report https://covid19.uk.gov.in/ To get Medical assistant and http://www.esanjeevaniopd.in/Register Doctor's consultation: Download app: Free Consultation from https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=in.hi Esanjeevani ed.esanjeevaniopd&hl=en_US Or call: 9412080703, 9412080622, 9412080686 Home Isolation Registration https://dsclservices.org.in/self-isolation.php Vaccination (Self Registration) https://selfregistration.cowin.gov.in/ www.cowin.gov.in For Plasma Donations https://covid19.uk.gov.in/donateplasma.aspx Daily Bulletin https://health.uk.gov.in/pages/display/140-novel- corona-virus-guidelines-and-advisory- Travelling to/from https://dsclservices.org.in/apply.php Uttarakhand Registration Any other Help Call 104 (24X7) / State Control Room 0135-2609500/ District Control Rooms of respective district for any 1 other help and assistance. for any queries and [email protected] suggestions Toll Free Number 104 State Covid 19 Control Room 0135 2609500 1. Almora 8. Pauri Garhwal 2. Bageshwar 9. Pithoragarh 3. Chamoli 10. Rudraprayag 4. Champawat 11. Tehri Garhwal 5. Deharadun 12. Udham Singh Nagar 6. Haridwar 13. Uttarkashi 7. Nainital VACCINATION For complaints regarding black marketing of medicines and oxygen in Uttarakhand. Landline No. 0135-2656202 and Mobile: 9412029536 2 District Almora Contact Details of District Administration Name of Officer Designation Mobile Email ID Number District Almora District Control Room 05962-237874 Shri Nitin Singh Bhaduria DM 9456593401 [email protected] Dr Savita Hyanki CMO 9411757084 [email protected] Dr. -

LIST of INDIAN CITIES on RIVERS (India)

List of important cities on river (India) The following is a list of the cities in India through which major rivers flow. S.No. City River State 1 Gangakhed Godavari Maharashtra 2 Agra Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 3 Ahmedabad Sabarmati Gujarat 4 At the confluence of Ganga, Yamuna and Allahabad Uttar Pradesh Saraswati 5 Ayodhya Sarayu Uttar Pradesh 6 Badrinath Alaknanda Uttarakhand 7 Banki Mahanadi Odisha 8 Cuttack Mahanadi Odisha 9 Baranagar Ganges West Bengal 10 Brahmapur Rushikulya Odisha 11 Chhatrapur Rushikulya Odisha 12 Bhagalpur Ganges Bihar 13 Kolkata Hooghly West Bengal 14 Cuttack Mahanadi Odisha 15 New Delhi Yamuna Delhi 16 Dibrugarh Brahmaputra Assam 17 Deesa Banas Gujarat 18 Ferozpur Sutlej Punjab 19 Guwahati Brahmaputra Assam 20 Haridwar Ganges Uttarakhand 21 Hyderabad Musi Telangana 22 Jabalpur Narmada Madhya Pradesh 23 Kanpur Ganges Uttar Pradesh 24 Kota Chambal Rajasthan 25 Jammu Tawi Jammu & Kashmir 26 Jaunpur Gomti Uttar Pradesh 27 Patna Ganges Bihar 28 Rajahmundry Godavari Andhra Pradesh 29 Srinagar Jhelum Jammu & Kashmir 30 Surat Tapi Gujarat 31 Varanasi Ganges Uttar Pradesh 32 Vijayawada Krishna Andhra Pradesh 33 Vadodara Vishwamitri Gujarat 1 Source – Wikipedia S.No. City River State 34 Mathura Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 35 Modasa Mazum Gujarat 36 Mirzapur Ganga Uttar Pradesh 37 Morbi Machchu Gujarat 38 Auraiya Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 39 Etawah Yamuna Uttar Pradesh 40 Bangalore Vrishabhavathi Karnataka 41 Farrukhabad Ganges Uttar Pradesh 42 Rangpo Teesta Sikkim 43 Rajkot Aji Gujarat 44 Gaya Falgu (Neeranjana) Bihar 45 Fatehgarh Ganges -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

Uttar Pradesh State Water Policy 2020

UTTAR PRADESH STATE WATER POLICY 2020 Submitted by: Uttar Pradesh Water Management & Regulatory Commission (UPWaMReC) Table of Contents Table of Contents 1. History of Water Resources Management in Uttar Pradesh: A perspective for the State Water Policy ............................................................................................................................... 5 2. Preamble ............................................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Need for a New Water Policy ..................................................................................... 6 2.2 Vision Statement ......................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Policy Objectives ......................................................................................................... 7 2.4 The Strategic Pillars .................................................................................................... 8 2.5 Guiding Principles ..................................................................................................... 10 2.6 Approaches ................................................................................................................ 11 3. Water Resources in Uttar Pradesh .................................................................................... 11 3.1 Geographical Variation in water availability ............................................................ 11 3.2 Total Water Availability ........................................................................................... -

Ganga As Perceived by Some Ganga Lovers Mother Ganga's Rights Are Our Rights

Ganga as Perceived by Some Ganga Lovers Mother Ganga’s Rights Are Our Rights Pujya Swami Chidanand Saraswati Nearly 500 million people depend every day on the Ganga and Her tributaries for life itself. Like the most loving of mothers, She has served us, nourished us and enabled us to grow as a people, without hesitation, without discrimination, without vacation for millennia. Regardless of what we have done to Her, the Ganga continues in Her steady fl ow, providing the waters that offer nourishment, livelihoods, faith and hope: the waters that represents the very life-blood of our nation. If one may think of the planet Earth as a body, its trees would be its lungs, its rivers would be its veins, and the Ganga would be its very soul. For pilgrims, Her course is a lure: From Gaumukh, where she emerges like a beacon of hope from icy glaciers, to the Prayag of Allahabad, where Mother Ganga stretches out Her glorious hands to become one with the Yamuna and Saraswati Rivers, to Ganga Sagar, where She fi nally merges with the ocean in a tender embrace. As all oceans unite together, Ganga’s reach stretches far beyond national borders. All are Her children. For perhaps a billion people, Mother Ganga is a living goddess who can elevate the soul to blissful union with the Divine. She provides benediction for infants, hope for worshipful adults, and the promise of liberation for the dying and deceased. Every year, millions come to bathe in Ganga’s waters as a holy act of worship: closing their eyes in deep prayer as they reverently enter the waters equated with Divinity itself. -

Post-Tehri Dam Irrigation Service and Modernization of Upper Ganga Canal System

POST-TEHRI DAM IRRIGATION SERVICE AND MODERNIZATION OF UPPER GANGA CANAL SYSTEM Ravindra Kumar1 ABSTRACT Multiple uses of Upper Ganga Canal (UGC) water- serving thirsty towns, major water feeder to Agra irrigation canals (of Yamuna basin), producing power at many UGC drops, presently irrigating an average 0.6 million ha against cultivable command area of 0.9 mha, generating water benefits @ US$ 1500/ha cropped area at the annual working cost of US $ 20/ha (2007-08) and revenue realized @ US $ 6/ha (based on irrigation rate of 1995) having cost of water @ US$ 0.10/m3 justifies its capacity modernization from existing 297 m3/s to 400 m3/s as a result of additional water 113 m3/s available post Tehri dam for water distribution in Kharif (wet season): 3 weeks on, one week off and in Rabi(dry season): 2 weeks on and two weeks off. Based on the ecological flow requirement for a specific reach of the river Ganga, the bare optimal flow need has been estimated as 72% for upper and 45 to 47% of mean annual run off natural for middle reaches respectively. SUMMARY & CONCLUSIONS The Ganges River, like most Indian rivers is highly degraded and regulated with over- abstraction of water posing a threat to its many river sub-basins. The combined effect of low flow and discharge of polluting effluent into River Ganga has caused severe deterioration in the quality of water. Vulnerability of 5 million people livelihoods and biota to climate change calls for prioritization of adaptation strategies. Three key questions are to be addressed: what impact does flow have on water quality? What impact does water quality changes have on biota; and what impact does water quality changes have on cultural and social aspects? To establish a framework for sustainable energy and water resources management in Upper Ganga river basin, it is concluded that dilution of pollution by releasing additional water from Tehri dam is not advisable at the cost of irrigation and hydropower generation which is another scarcer resource. -

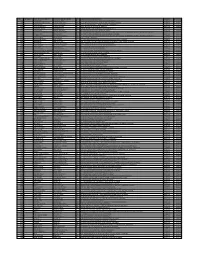

S. No. Post Code Name of the Candidate Father's

S. NO. POST CODE NAME OF THE CANDIDATE FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME CAT ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE REMARKS DATE OF EXAM 3351 02 VIPIN KUMAR MADAN LAL SHAH SC VILL & POST DANG (KARAKOI), KIRTINAGAR, TEHRI GARHWAL ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3352 01 DHEERENDRA SINGH GAIRA MADAN SINGH GAIRA GEN VILL. KAMALUWAGANJA GAUR, NEAR GHIMSI, HALDWANI, NAINITAL ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3353 01 SONIA MADAN KISHAN LAL MADAN GEN 13/43, DANDIPUR MOHALLA, NEAR TILAK ROAD, DEHRADUN ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3354 02 VINAY KUMAR ARYA MADAN LAL SHAH SC VILL. CHARKHEN, PO, KHURPATAL, NAINITAL ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3355 01 MAHENDRA GUPTA BABURAM GUPTA GEN RAJPURA MARKET, TANAKPUR ROAD, HALDWANI, NAINITAL ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3356 01 OMKAR SINGH MADAN PAL SINGH SC VILL. MANDUWAKHERA, POST JASPUR, US NAGAR ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3357 02 BHARTENDU SHANKAR PANDEY BALLABH BHAI PANDEY GEN NO. 182, MAHARASHTRA NIWAS RAILWAY ROAD, SUBHASH BANAWANDI, NEAR PRASAD HOSPITAL, RISHIKESH, DEHRADUN ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3358 01 SUNEELA RANA PAMESH SINGH ST VILL. HARRYA, POST NANAKMATTA, TEHSIL SITARGANJ, US NAGAR ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3359 01 BHARTENDU SHANKAR PANDEY BALLABH BHAI PANDEY GEN NO. 182, MAHARASHTRA NIWAS RAILWAY ROAD, SUBHASH BANAWANDI, NEAR PRASAD HOSPITAL, RISHIKESH, DEHRADUN ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3360 01 NEERAJ KUMAR SHYAM SINGH GEN 21/6, ECE ROAD, DEHRADUN ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3361 02 MANOJ KUMAR ARYA RAM LAL ARYA SC VILL. ANU, NEAR AKASH RESORT SHIKSHA BHAWAN ROAD, BHIMTAL, NAINITAL ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3362 01 KAMLA BHATT PRAN DUTT BHATT GEN 1508, TA COLONY, G.B. PANT KRISHI & PRODHOGIKI UNIVERSITY, PANT NAGAR, US NAGAR ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3363 01 POOJA PANU BHAWAN SINGH PANU GEN SAHNI TRANSPORT, NEAR NAGAR PALIKA, PITHORAGARH ACCEPTED 8-Sep-16 3364 01 RESHU SHARMA GOPAL DATT SHARMA GEN VILL. -

1. Sh. Amit Joshi Through E-Mail ([email protected])

Annexure List of Respondents 1. Sh. Amit Joshi through E-mail ([email protected]). 2. Sh. L.S. Chamyal, Factory Manager, M/s Khatema Fibres Ltd., UPSIDC Industrial Area, Khatima-262308, Uttarakhand. 3. Sh. Achal Sharma, President, M/s East West Products Ltd., Lohia Head Road, Khatima-262308, Udham Singh Nagar. 4. Sh. Shakeel A. Siddiqui, Sr. General Manager (Finance), M/s Kashi Vishwanath Textile Mill (P) Ltd., 5th KM, Stone, Ramnagar Road, Kashipur-244713, Distt. Udham Singh Nagar. 5. M/s BST Textile Mills Pvt. Ltd., Plot 9, Sector 9, IIE, SIDCUL, Pantnagar, Rudrapur- 263153, Udham Singh Nagar. 6. Dr. Ganesh Upadhayaya, Uttarakhand State Congress Committee, Off.-Congress Bhawan, 21, Rajpur Road, Dehradun-248001. 7. Sh. Teeka Singh Saini, Former State General Secretary, Kisan Congress, Uttarakhand. 8. Sh. R.K. Singh, Head (CPED & E), M/s Tata Motors Ltd., Plot No. 1, Sector 11, Integrated Industrial Estate, SIDCUL, Pantnagar-263153, Udhamsingh Nagar. 9. Sh. Kuldeep Singh Cheema, Bhartiya Kisan Union, Village-Dakiya Kalan, Post Off.- Dakiya No.-I, Distt. Udham Singh Nagar. 10. Sh. Naveen Chandra Joshi, S/o Late Sh. Tara Datt Joshi, Former Warrant Officer, Resident-Bakshi Khola, Post Off. & District Almora-263601, Uttarakhand. 11. Sh. Amar Singh Karki, Mohalla Makedi, Post Off. & District Almora-263601, Uttarakhand. 12. Sh. Pooran Chandra Tiwari, General Secretary, Uttarakhand Lok Vahini, “Tiwari Sadan”, Talla Galli, Jakhandevi, District Almora, Uttarakhand. 13. Sh. P.S. Mehra, Secretary, Retired Central Employees Welfare Committee, Address- C/o Sh. Ravindra Nath Verma (Retd. Postmaster), Baans Gali, Johri Market, District Almora, Uttarakhand. 14. Sh. Sanjay Kumar Agrawal, Director & General Secretary, Shree Karuna Jan Kalyan Samiti (Regd.), Sanjay Bhawan, Malla Joshi Khola, Almora, Uttarakhand-263601. -

For Brick Manufacturing from Lease Area Of

Proposed Digging / Excavation of “Brick Earth” for Brick manufacturing FORM - 1 from Lease area of Village Akbarpur Dhodheki, Pargana Manglaur, Tehsil Roorkee, District Haridwar, Uttarakhand APPENDIX- I FORM- 1 (I) Basic Information Sl. Item Details No. 1. Name of the Project / s Proposed Digging / Excavation of “Brick Earth” for Brick manufacturing from Lease area of village Akbarpur Dhodheki, Pargana Manglaur, Tehsil – Roorkee, District Haridwar, by M/s Kamal Brick Field, Village – Akbarpur Dhodheki, Tehsil – Roorkee, District, Haridwar, Uttarakhand. 2. Sl. No. in the Schedule 1 (a) 3. Proposed capacity / area / length / tonnage 16894.2 Tonnes (14078.5 Cubic Meter) / / to be handled / command area / lease Digging Lease Area 0.761 Hectare. area / number of Wells to be drilled Excavation / Digging would be done up to 1.85 Meters below general ground level. 4. New/Expansion / Modernization New Excavation 5. Existing Capacity /Area etc. 0.761 Hectare 6. Category of Project i.e. ‘A’ or ‘B’ “B2” 7. Does it attract the general condition? If yes No Please specify. 8. Does it attract the specific condition? If yes No Please specify 9. Location Plot/Survey/ Khasra No Khasra No. 59 Akbarpur Dhodheki Village Pargana Manglaur Tehsil Roorkee District Haridwar State Uttarakhand 10. Nearest Railway station/airport along with Landhaura Railway : 4.15 Km NE Distance in Km Station M/s KAMAL BRICK FIELD 1 Proposed Digging / Excavation of “Brick Earth” for Brick manufacturing FORM - 1 from Lease area of Village Akbarpur Dhodheki, Pargana Manglaur, Tehsil Roorkee, District Haridwar, Uttarakhand Jolly Grant Airport : 51.74 Km NE 11. Nearest Town, City, District Headquarters Manglaur – 3.90 Km NW along with distance in Km Haridwar – 30.23 Km NE 12. -

Directory of E-Mail Accounts of Uttarakhand Created on NIC Email Server

Directory of E-mail Accounts of Uttarakhand Created on NIC Email Server Disclaimer : For email ids enlisted below, the role of NIC Uttarakhand State Unit is limited only as a service provider for technical support for email-ids created over NIC’s Email Server, over the demand put up by various Government Depratments in Uttarakhand from time to time. Therefore NIC does not take responsibility on how an email account is used and consequences of it’s use. Since there may also be a possibility that these Departments might be having varied preferences for using email ids of various service providers (such as yahoo, rediffmail, gmail etc etc) other than NIC email ids for various official purposes. Therefore before corresponding with an email over these accounts, it is advised to confirm official email account directly from the department / user. As per policy NIC's email account once not used continuously for 90 days gets disabled. Last Updated on :- 25/10/2012 DEPARTMENT DESIGNATION HQs EMAIL-ID DESCRIPTION Accountant General Accountant General State Head Quarter [email protected] Accountant General(A & E) Agriculture Hon'ble Minister State Head Quarter [email protected] Minister of Agriculture, GoU Agriculture Secretary State Head Quarter [email protected] Secretary, GoUK Aditional Director of Agriculture Aditional Director State Head Quarter [email protected] Agriculture,Dehradun,Uttarakhand Deputy Director Technical Analysis of Agriculture Deputy Director State Head Quarter [email protected] Agriculture ,Dehradun,Uttarakhand Deputy -

Office of the Accountant General (Audit), Uttarakhand, Dehradun

Annual Technical Inspection Report on Panchayati Raj Institutions and Urban Local Bodies for the year ended 31 March 2015 Office of the Accountant General (Audit), Uttarakhand, Dehradun Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Particulars Paragraph Page No. Preface v Executive Summary vii PART- I PANCHAYATI RAJ INSTITUTIONS CHAPTER -1 PROFILE OF PANCHAYATI RAJ INSTITUTIONS (PRIs) Introduction 1.1 1 Maintenance of Accounts 1.2 1 Entrustment of Audit (Audit Arrangements) 1.3 2 Organizational Structure of Panchayati Raj Institutions in 1.4 3 Uttarakhand Standing Committees 1.5 4 Institutional Arrangements for Implementation of Schemes 1.6 5 Financial Profile 1.7 5 Accountability Framework (Internal Control System) 1.8 7 Audit mandate of Primary Auditor (Director of Audit) 1.9 7 Accounting System 1.10 7 Audit Coverage 1.11 8 Response to Audit Observations 1.12 10 CHAPTER- 2 RESULTS OF AUDIT OF PANCHAYATI RAJ INSTITUTIONS (PRIS) Border Area Development Programme 2.1 13 Rashtriya Sam Vikas Yojana 2.2 13 MLA Local Area Development Scheme 2.3 14 Scheduled Castes Sub-Plan 2.4 15 Loss of Lease Rent 2.5 15 Non-realisation of Revenue 2.6 15 Unsettled Miscellaneous Advances 2.7 16 Non-imposition of Circumstances and Property tax 2.8 16 Irregular Payments 2.9 16 Non / irregular Deduction of Royalty 2.10 17 Loss of Revenue 2.11 17 Loss due to improper allotment process 2.12 18 Improper Maintenance of the Assets 2.13 18 i Table of Contents PART- II URBAN LOCAL BODIES CHAPTER-3 PROFILE OF URBAN LOCAL BODIES (ULBs) Introduction 3.1 19 Maintenance of Accounts -

List of General Candidates for Uttarakhand Higher Judicial Service Preliminary Examination – 2015 (Direct Recruitment)

LIST OF GENERAL CANDIDATES FOR UTTARAKHAND HIGHER JUDICIAL SERVICE PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION – 2015 (DIRECT RECRUITMENT) Roll Name of the Fathers Address of Date of Registration Objections No. Candidate Name Candidates Birth Number in the applications 01. Sri Laxmi Sri M- 86, Ramganga 01-07-1973 6907/2007 Chand Jain Chintaman Vihar Phase-2, Near- Allahabad U.P. Jain Mit Guest House Moradabad Pin- 244001 02. Sri Nagendra Sri 12/3, GA, Govind 10-06-1975 3156/2006 (i). No Singh Bisen Deependra Nagar (Karbala) U.P. certificate Singh Bisen Allahabad, enclosed for Pin-211016 name/ D.O.B. verification. (ii) Experience cum Character Certificate not attached. 03. Sri Satender Sri Chamber No. 32, 18-12-1973 11147/2000 Singh Vishwanath Civil Court U.P. & Kushwaha Singh Compound District 4115/2004 Kushwaha Court, Dehradun, U.A. Pin-248001 04. Sri Sri G.D. Joshi Amrawati Colony-III, 15-06-1971 9014/2001 Ghanshyam Talli Bamori U.P.& Joshi Haldwani Nainital, 4463/2004 Pin-263141 U.K. 05. Sri Avinash Late Sri D-59/76-A, 07-11-1973 4908/2006 Pandey Mahesh Mahmoor Ganj, Prasad Varanasi, Pin- Pandey 221010 06. Sri Amit Sri Kali 1403, New Shiv Puri, 04-09-1976 D/2532-E/1999 (i) Experience Sharma Charan Railway Road, certificate & Sharma Hapur, District- character Haridwar, U.P., Pin- certificate not 245101 enclosed. (ii) The registration no. filled in concernd column differs from the registration no. mentioned in the certificate of Bar council. 07. Sri Ashwani Sri Chandra 15-11/2538/1, Near 13-12-1977 D/1464/2001 Experience Sharma Prakash Asodiya Handloom, Delhi cum character Sharma Gandhi Vihar, Hapur, certificate has Distt.