Open Sesame the Password Hashing Competition and Argon2 Jos Wetzels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GPU-Based Password Cracking on the Security of Password Hashing Schemes Regarding Advances in Graphics Processing Units

Radboud University Nijmegen Faculty of Science Kerckhoffs Institute Master of Science Thesis GPU-based Password Cracking On the Security of Password Hashing Schemes regarding Advances in Graphics Processing Units by Martijn Sprengers [email protected] Supervisors: Dr. L. Batina (Radboud University Nijmegen) Ir. S. Hegt (KPMG IT Advisory) Ir. P. Ceelen (KPMG IT Advisory) Thesis number: 646 Final Version Abstract Since users rely on passwords to authenticate themselves to computer systems, ad- versaries attempt to recover those passwords. To prevent such a recovery, various password hashing schemes can be used to store passwords securely. However, recent advances in the graphics processing unit (GPU) hardware challenge the way we have to look at secure password storage. GPU's have proven to be suitable for crypto- graphic operations and provide a significant speedup in performance compared to traditional central processing units (CPU's). This research focuses on the security requirements and properties of prevalent pass- word hashing schemes. Moreover, we present a proof of concept that launches an exhaustive search attack on the MD5-crypt password hashing scheme using modern GPU's. We show that it is possible to achieve a performance of 880 000 hashes per second, using different optimization techniques. Therefore our implementation, executed on a typical GPU, is more than 30 times faster than equally priced CPU hardware. With this performance increase, `complex' passwords with a length of 8 characters are now becoming feasible to crack. In addition, we show that between 50% and 80% of the passwords in a leaked database could be recovered within 2 months of computation time on one Nvidia GeForce 295 GTX. -

Computationally Data-Independent Memory Hard Functions

Computationally Data-Independent Memory Hard Functions Mohammad Hassan Ameri∗ Jeremiah Blocki† Samson Zhou‡ November 18, 2019 Abstract Memory hard functions (MHFs) are an important cryptographic primitive that are used to design egalitarian proofs of work and in the construction of moderately expensive key-derivation functions resistant to brute-force attacks. Broadly speaking, MHFs can be divided into two categories: data-dependent memory hard functions (dMHFs) and data-independent memory hard functions (iMHFs). iMHFs are resistant to certain side-channel attacks as the memory access pattern induced by the honest evaluation algorithm is independent of the potentially sensitive input e.g., password. While dMHFs are potentially vulnerable to side-channel attacks (the induced memory access pattern might leak useful information to a brute-force attacker), they can achieve higher cumulative memory complexity (CMC) in comparison than an iMHF. In particular, any iMHF that can be evaluated in N steps on a sequential machine has CMC at 2 most N log log N . By contrast, the dMHF scrypt achieves maximal CMC Ω(N 2) — though O log N the CMC of scrypt would be reduced to just (N) after a side-channel attack. In this paper, we introduce the notion ofO computationally data-independent memory hard functions (ciMHFs). Intuitively, we require that memory access pattern induced by the (ran- domized) ciMHF evaluation algorithm appears to be independent from the standpoint of a computationally bounded eavesdropping attacker — even if the attacker selects the initial in- put. We then ask whether it is possible to circumvent known upper bound for iMHFs and build a ciMHF with CMC Ω(N 2). -

Argon and Argon2

Argon and Argon2 Designers: Alex Biryukov, Daniel Dinu, and Dmitry Khovratovich University of Luxembourg, Luxembourg [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] https://www.cryptolux.org/index.php/Password https://github.com/khovratovich/Argon https://github.com/khovratovich/Argon2 Version 1.1 of Argon Version 1.0 of Argon2 31th January, 2015 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Argon 5 2.1 Specification . 5 2.1.1 Input . 5 2.1.2 SubGroups . 6 2.1.3 ShuffleSlices . 7 2.2 Recommended parameters . 8 2.3 Security claims . 8 2.4 Features . 9 2.4.1 Main features . 9 2.4.2 Server relief . 10 2.4.3 Client-independent update . 10 2.4.4 Possible future extensions . 10 2.5 Security analysis . 10 2.5.1 Avalanche properties . 10 2.5.2 Invariants . 11 2.5.3 Collision and preimage attacks . 11 2.5.4 Tradeoff attacks . 11 2.6 Design rationale . 14 2.6.1 SubGroups . 14 2.6.2 ShuffleSlices . 16 2.6.3 Permutation ...................................... 16 2.6.4 No weakness,F no patents . 16 2.7 Tweaks . 17 2.8 Efficiency analysis . 17 2.8.1 Modern x86/x64 architecture . 17 2.8.2 Older CPU . 17 2.8.3 Other architectures . 17 3 Argon2 19 3.1 Specification . 19 3.1.1 Inputs . 19 3.1.2 Operation . 20 3.1.3 Indexing . 20 3.1.4 Compression function G ................................. 21 3.2 Features . 22 3.2.1 Available features . 22 3.2.2 Server relief . 23 3.2.3 Client-independent update . -

Second Preimage Attacks on Dithered Hash Functions

Second Preimage Attacks on Dithered Hash Functions Elena Andreeva1, Charles Bouillaguet2, Pierre-Alain Fouque2, Jonathan J. Hoch3, John Kelsey4, Adi Shamir2,3, and Sebastien Zimmer2 1 SCD-COSIC, Dept. of Electrical Engineering, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, [email protected] 2 École normale supérieure (Département d’Informatique), CNRS, INRIA, {Charles.Bouillaguet,Pierre-Alain.Fouque,Sebastien.Zimmer}@ens.fr 3 Weizmann Institute of Science, {Adi.Shamir,Yaakov.Hoch}@weizmann.ac.il 4 National Institute of Standards and Technology, [email protected] Abstract. We develop a new generic long-message second preimage at- tack, based on combining the techniques in the second preimage attacks of Dean [8] and Kelsey and Schneier [16] with the herding attack of Kelsey and Kohno [15]. We show that these generic attacks apply to hash func- tions using the Merkle-Damgård construction with only slightly more work than the previously known attack, but allow enormously more con- trol of the contents of the second preimage found. Additionally, we show that our new attack applies to several hash function constructions which are not vulnerable to the previously known attack, including the dithered hash proposal of Rivest [25], Shoup’s UOWHF[26] and the ROX hash construction [2]. We analyze the properties of the dithering sequence used in [25], and develop a time-memory tradeoff which allows us to apply our second preimage attack to a wide range of dithering sequences, including sequences which are much stronger than those in Rivest’s proposals. Fi- nally, we show that both the existing second preimage attacks [8, 16] and our new attack can be applied even more efficiently to multiple target messages; in general, given a set of many target messages with a total of 2R message blocks, these second preimage attacks can find a second preimage for one of those target messages with no more work than would be necessary to find a second preimage for a single target message of 2R message blocks. -

PHC: Status Quo

PHC: status quo JP Aumasson @veorq / http://aumasson.jp academic background principal cryptographer at Kudelski Security, .ch applied crypto research and outreach BLAKE, BLAKE2, SipHash, NORX Crypto Coding Standard Password Hashing Competition Open Crypto Audit Project board member do you use passwords? this talk might interest you! Oct 2013 "hash" = 3DES-ECB( static key, password ) users' hint made the guess game easy... (credit Jeremi Gosney / Stricture Group) May 2014; "encrypted passwords" (?) last week that's only the reported/published cases Lesson if Adobe, eBay, and Avast fail to protect their users' passwords, what about others? users using "weak passwords"? ITsec people using "weak defenses"? developers using "weak hashes"? cryptographers, who never bothered? agenda 1. how (not) to protect passwords 2. the Password Hashing Competition (PHC) 3. the 24-2 PHC candidates 4. next steps, and how to contribute WARNING this is NOT about bikeshed topics as: password policies password managers password-strength meters will-technology-X-replace-passwords? 1. how (not) to protect passwords solution of the 60's store "password" or the modern alternative: obviously a bad idea (assuming the server and its DB are compromised) solution of the early 70's store hash("password") "one-way": can't be efficiently inverted vulnerable to: ● efficient dictionary attacks and bruteforce ● time-memory tradeoffs (rainbow tables, etc.) solution of the late 70's store hash("password", salt) "one-way": can't be efficiently inverted immune to time-memory tradeoffs vulnerable to: ● dictionary attacks and bruteforce (but has to be repeated for different hashes) solution of the 2000's store hash("password", salt, cost) "one-way": can't be efficiently inverted immune to time-memory tradeoffs inefficient dictionary attacks and bruteforce main ideas: ● be "slow" ● especially on attackers' hardware (GPU, FPGA) => exploit fast CPU memory access/writes PBKDF2 (Kaliski, 2000) NIST and PKCS standard in Truecrypt, iOS, etc. -

Truecrack Bruteforcing Per Volumi Truecrypt

Luca Vaccaro http://code.google.com/p/truecrack/ [email protected] User development guide. TrueCrypt © . software application used for on-the-fly encryption (OTFE). TrueCrack . bruteforce password cracker for TrueCrypt © (Copyrigth) volume files, optimazed with Nvidia Cuda technology. This software is Based on TrueCrypt, freely available athttp://www.truecrypt.org/ Master key . Crypt the volume of data. Generated one time in the volume creation phase from random value. Write inside the header section of the volume file. Header key . Crypt the header section of the volume file. Generated from a user password and a random salt (64 bytes). The salt is write in plain text in the first 64 bytes of volume file. Hard disk encryption: . Standard block cipher: XTS . Hash availables: AES, Serpent, Twofish . Default: AES Key derivation function: . Standard algorithm: PBKDF2 . Hash availables: RIPEMD160, SHA-512, Whirpool . Default: RIPEMD160 Master Header Key Key Plain Cipher Volume data data + file header Opening a TrueCrypt volume means to retrieve the Master Key from the Header section In the Header there are some fields (true, crc32) for checking the success of the decipher operation . If the password is right or wrong Header key User password salt Volume Master file key CUDA or Compute Unified Device Architecture is a parallel computing architecture developed by Nvidia. CUDA gives developers access to the virtual instruction set and memory of the parallel computational elements in CUDA GPUs. Each GPU is a collection of multicores. Each core can run mmore cuda «block», and each block can run a numbers of parallel «thread» 1. Level of parallilism : block 2. -

Analysis of Password Cracking Methods & Applications

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Honors Research Projects College Spring 2015 Analysis of Password Cracking Methods & Applications John A. Chester The University Of Akron, [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Information Security Commons Recommended Citation Chester, John A., "Analysis of Password Cracking Methods & Applications" (2015). Honors Research Projects. 7. http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/7 This Honors Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Analysis of Password Cracking Methods & Applications John A. Chester The University of Akron Abstract -- This project examines the nature of password cracking and modern applications. Several applications for different platforms are studied. Different methods of cracking are explained, including dictionary attack, brute force, and rainbow tables. Password cracking across different mediums is examined. Hashing and how it affects password cracking is discussed. An implementation of two hash-based password cracking algorithms is developed, along with experimental results of their efficiency. I. Introduction Password cracking is the process of either guessing or recovering a password from stored locations or from a data transmission system [1]. -

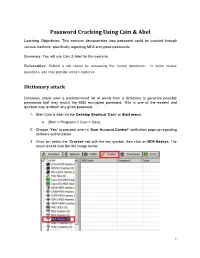

Password Cracking Using Cain & Abel

Password Cracking Using Cain & Abel Learning Objectives: This exercise demonstrates how password could be cracked through various methods, specifically regarding MD5 encrypted passwords. Summary: You will use Cain & Abel for this exercise. Deliverables: Submit a lab report by answering the review questions. In some review questions, you may provide screen captures. Dictionary attack Dictionary attack uses a predetermined list of words from a dictionary to generate possible passwords that may match the MD5 encrypted password. This is one of the easiest and quickest way to obtain any given password. 1. Start Cain & Abel via the Desktop Shortcut ‘Cain’ or Start menu. a. (Start > Programs > Cain > Cain). 2. Choose ‘Yes’ to proceed when a ‘User Account Control’ notification pops up regarding software authorization. 3. Once on, select the ‘Cracker’ tab with the key symbol, then click on MD5 Hashes. The result should look like the image below. 1 Collaborative Virtual Computer Lab (CVCLAB) Penn State Berks 4. As you might have noticed we don’t have any passwords to crack, thus for the next few steps we will create our own MD5 encrypted passwords. First, locate the Hash Calculator among a row of icons near the top. Open it. 5. Next, type into ‘Text to Hash’ the word password. It will generate a list of hashes pertaining to different types of hash algorithms. We will be focusing on MD5 hash so copy it. Then exit calculator by clicking ‘Cancel’ (Fun Fact: Hashes are case sensitive so any slight changes to the text will change the hashes generated, try changing a letter or two and you will see. -

Modern Password Security for System Designers What to Consider When Building a Password-Based Authentication System

Modern password security for system designers What to consider when building a password-based authentication system By Ian Maddox and Kyle Moschetto, Google Cloud Solutions Architects This whitepaper describes and models modern password guidance and recommendations for the designers and engineers who create secure online applications. A related whitepaper, Password security for users, offers guidance for end users. This whitepaper covers the wide range of options to consider when building a password-based authentication system. It also establishes a set of user-focused recommendations for password policies and storage, including the balance of password strength and usability. The technology world has been trying to improve on the password since the early days of computing. Shared-knowledge authentication is problematic because information can fall into the wrong hands or be forgotten. The problem is magnified by systems that don't support real-world secure use cases and by the frequent decision of users to take shortcuts. According to a 2019 Yubico/Ponemon study, 69 percent of respondents admit to sharing passwords with their colleagues to access accounts. More than half of respondents (51 percent) reuse an average of five passwords across their business and personal accounts. Furthermore, two-factor authentication is not widely used, even though it adds protection beyond a username and password. Of the respondents, 67 percent don’t use any form of two-factor authentication in their personal life, and 55 percent don’t use it at work. Password systems often allow, or even encourage, users to use insecure passwords. Systems that allow only single-factor credentials and that implement ineffective security policies add to the problem. -

A Full Key Recovery Attack on HMAC-AURORA-512

A Full Key Recovery Attack on HMAC-AURORA-512 Yu Sasaki NTT Information Sharing Platform Laboratories, NTT Corporation 3-9-11 Midori-cho, Musashino-shi, Tokyo, 180-8585 Japan [email protected] Abstract. In this note, we present a full key recovery attack on HMAC- AURORA-512 when 512-bit secret keys are used and the MAC length is 512-bit long. Our attack requires 2257 queries and the off-line com- plexity is 2259 AURORA-512 operations, which is significantly less than the complexity of the exhaustive search for a 512-bit key. The attack can be carried out with a negligible amount of memory. Our attack can also recover the inner-key of HMAC-AURORA-384 with almost the same complexity as in HMAC-AURORA-512. This attack does not recover the outer-key of HMAC-AURORA-384, but universal forgery is possible by combining the inner-key recovery and 2nd-preimage attacks. Our attack exploits some weaknesses in the mode of operation. keywords: AURORA, DMMD, HMAC, Key recovery attack 1 Description 1.1 Mode of operation for AURORA-512 We briefly describe the specification of AURORA-512. Please refer to Ref. [2] for details. An input message is padded to be a multiple of 512 bits by the standard MD message padding, then, the padded message is divided into 512-bit message blocks (M0;M1;:::;MN¡1). 256 512 256 In AURORA-512, compression functions Fk : f0; 1g £f0; 1g ! f0; 1g 256 512 256 512 and Gk : f0; 1g £ f0; 1g ! f0; 1g , two functions MF : f0; 1g ! f0; 1g512 and MFF : f0; 1g512 ! f0; 1g512, and two initial 256-bit chaining U D 1 values H0 and H0 are defined . -

BLAKE2: Simpler, Smaller, Fast As MD5

BLAKE2: simpler, smaller, fast as MD5 Jean-Philippe Aumasson1, Samuel Neves2, Zooko Wilcox-O'Hearn3, and Christian Winnerlein4 1 Kudelski Security, Switzerland [email protected] 2 University of Coimbra, Portugal [email protected] 3 Least Authority Enterprises, USA [email protected] 4 Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany [email protected] Abstract. We present the hash function BLAKE2, an improved version of the SHA-3 finalist BLAKE optimized for speed in software. Target applications include cloud storage, intrusion detection, or version control systems. BLAKE2 comes in two main flavors: BLAKE2b is optimized for 64-bit platforms, and BLAKE2s for smaller architectures. On 64- bit platforms, BLAKE2 is often faster than MD5, yet provides security similar to that of SHA-3: up to 256-bit collision resistance, immunity to length extension, indifferentiability from a random oracle, etc. We specify parallel versions BLAKE2bp and BLAKE2sp that are up to 4 and 8 times faster, by taking advantage of SIMD and/or multiple cores. BLAKE2 reduces the RAM requirements of BLAKE down to 168 bytes, making it smaller than any of the five SHA-3 finalists, and 32% smaller than BLAKE. Finally, BLAKE2 provides a comprehensive support for tree-hashing as well as keyed hashing (be it in sequential or tree mode). 1 Introduction The SHA-3 Competition succeeded in selecting a hash function that comple- ments SHA-2 and is much faster than SHA-2 in hardware [1]. There is nev- ertheless a demand for fast software hashing for applications such as integrity checking and deduplication in filesystems and cloud storage, host-based intrusion detection, version control systems, or secure boot schemes. -

Implementation and Performance Analysis of PBKDF2, Bcrypt, Scrypt Algorithms

Implementation and Performance Analysis of PBKDF2, Bcrypt, Scrypt Algorithms Levent Ertaul, Manpreet Kaur, Venkata Arun Kumar R Gudise CSU East Bay, Hayward, CA, USA. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract- With the increase in mobile wireless or data lookup. Whereas, Cryptographic hash functions are technologies, security breaches are also increasing. It has used for building blocks for HMACs which provides become critical to safeguard our sensitive information message authentication. They ensure integrity of the data from the wrongdoers. So, having strong password is that is transmitted. Collision free hash function is the one pivotal. As almost every website needs you to login and which can never have same hashes of different output. If a create a password, it’s tempting to use same password and b are inputs such that H (a) =H (b), and a ≠ b. for numerous websites like banks, shopping and social User chosen passwords shall not be used directly as networking websites. This way we are making our cryptographic keys as they have low entropy and information easily accessible to hackers. Hence, we need randomness properties [2].Password is the secret value from a strong application for password security and which the cryptographic key can be generated. Figure 1 management. In this paper, we are going to compare the shows the statics of increasing cybercrime every year. Hence performance of 3 key derivation algorithms, namely, there is a need for strong key generation algorithms which PBKDF2 (Password Based Key Derivation Function), can generate the keys which are nearly impossible for the Bcrypt and Scrypt.