A Detailed Morpho-Kinematic Model of the Eskimo, Ngc 2392

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experiencing Hubble

PRESCOTT ASTRONOMY CLUB PRESENTS EXPERIENCING HUBBLE John Carter August 7, 2019 GET OUT LOOK UP • When Galaxies Collide https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HP3x7TgvgR8 • How Hubble Images Get Color https://www.youtube.com/watch? time_continue=3&v=WSG0MnmUsEY Experiencing Hubble Sagittarius Star Cloud 1. 12,000 stars 2. ½ percent of full Moon area. 3. Not one star in the image can be seen by the naked eye. 4. Color of star reflects its surface temperature. Eagle Nebula. M 16 1. Messier 16 is a conspicuous region of active star formation, appearing in the constellation Serpens Cauda. This giant cloud of interstellar gas and dust is commonly known as the Eagle Nebula, and has already created a cluster of young stars. The nebula is also referred to the Star Queen Nebula and as IC 4703; the cluster is NGC 6611. With an overall visual magnitude of 6.4, and an apparent diameter of 7', the Eagle Nebula's star cluster is best seen with low power telescopes. The brightest star in the cluster has an apparent magnitude of +8.24, easily visible with good binoculars. A 4" scope reveals about 20 stars in an uneven background of fainter stars and nebulosity; three nebulous concentrations can be glimpsed under good conditions. Under very good conditions, suggestions of dark obscuring matter can be seen to the north of the cluster. In an 8" telescope at low power, M 16 is an impressive object. The nebula extends much farther out, to a diameter of over 30'. It is filled with dark regions and globules, including a peculiar dark column and a luminous rim around the cluster. -

Lecture 2, Galaxy Number Counts and Luminosity Functions

Galaxies 626 Lecture 2: Galaxy number counts and luminosity functions How much of the extragalactic background light can we identify, and how much is unidentified (unresolved)? The next step is to count all the galaxies we can find and see how much light they contain So we now want to form the galaxy number counts at all wavelengths B, R, z/ 15/ x 15/ B (1.7hrs) R (5.2hrs) z’ (3.9hrs) B (27) R (26.4) z’ (25.4) Optical Image Capak et al. 2003 Measuring Galaxy Luminosities Galaxies, unlike stars, are not point sources The Hubble Space Telescope can resolve (i.e. detect the extended nature of) essentially all galaxies Even from the ground, most galaxies can easily be distinguished from stars morphologically and on the basis of their colors Measuring Galaxy Luminosities Define the surface brightness of a galaxy I as the amount of light from the galaxy per square arcsecond on the sky Consider a small square patch, of side D, in a galaxy at distance d: d D Angle patch subtends on sky α = D/d Finding Galaxies in an Image Finding galaxies in an image and constructing the number counts is the subject of the first student project Essentially we look for all objects above a limiting surface brightness and covering more than a specified area SExtractor is a commonly used package 20 cm Radio Image from the VLA Number Counts We then need to measure the fluxes of all the objects that we find The number counts are simply the number of objects we find in a given flux or magnitude bin per unit area of the sky Measuring Galaxy Luminosities Consider again -

Surface Brightness Profiles

AST222 Winter 2006 Supplementary Notes: Galaxy Surface Brightness Pro¯les The fundamental way we characterize the morphology of galaxies is through their surface brightness pro¯les. The light from galaxies follows a distribution of brightness on the night sky given by I(x; y) where I is the intensity or surface brightness distribution measured in units of luminosity per unit area at position (x; y) where the area is either in physical units (pc2) or an angular area in square arcseconds. The intensity is often represented by a radially-averaged function, I(R). The total luminosity of a galaxy is then just: 1 Ltot = 2¼ I(R)RdR (1) Z0 Astronomers usually quote surface brightness in units of magnitudes per square arcsec denoted by the symbol ¹. The quantity ¹ represents the apparent magnitude of the equivalent total light observed in a square arcsecond at di®erent points in the distribution. It can be related to the physical surface brightness pro¯le through: ¹ = 2:5 log10 I + C (2) ¡ ¡2 If I is measured in L¯ pc then the constant C can be found by going back to the distance modulus formula and determining the amount of light in a square arcsec for a galaxy observed at distance d (in pc) i.e. the light in a sq. arcsec is: L = Id2±2 (3) where ± = 1" = 1=206265 radians. The distance modulus formula is: m = M + 5 log10 d=(1pc) 5 (4) ¡ where M is the absolute magnitude of the star given in terms of the solar absolute magnitude M¯ by: M = 2:5 log10 L=L¯ + M¯ (5) ¡ (M¯ is the absolute magnitude of the sun not to be confused with the solar mass). -

The Number, Luminosity, and Mass Density of Spiral Galaxies As

The numb er luminosity and mass density of spiral galaxies as a function of surface brightness Stacy S McGaugh Institute of Astronomy University of Cambridge Madingley Road Cambridge CB HA ABSTRACT I give analytic expressions for the relative numb er luminosity and mass density of disc galaxies as a function of surface brightness These surface brightness distributions are asymmetric with long tails to lower surface brightnesses This asymmetry induces systematic errors in most determinations of the galaxy luminosity function Galaxies of low surface brightness exist in large numb ers but the additional contribution to the integrated luminosity density is mo dest probably Key words galaxies formation galaxies fundamental parameters galaxies general galaxies luminosity function mass function galaxies spiral galaxies structure Accepted for publication in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Present address Department of Terrestrial Magnetism Carnegie Institution of Wash ington Broad Branch Road NW Washington DC USA INTRODUCTION The space density of Low Surface Brightness LSB galaxies has long b een a contro versial and confusing sub ject It is basic to our inventory of the contents of the universe and is crucial to many asp ects of extragalactic astronomy For example the density of LSB galaxies has an impact on the luminosity function faint galaxy numb er counts Ly absorption systems and theories of galaxy formation In this pap er I derive analytic expressions which quantify the density of discs of all surface -

The Cosmic Distance Scale • Distance Information Is Often Crucial to Understand the Physics of Astrophysical Objects

The cosmic distance scale • Distance information is often crucial to understand the physics of astrophysical objects. This requires knowing the basic properties of such an object, like its size, its environment, its location in space... • There are essentially two ways to derive distances to astronomical objects, through absolute distance estimators or through relative distance estimators • Absolute distance estimators Objects for whose distance can be measured directly. They have physical properties which allow such a measurement. Examples are pulsating stars, supernovae atmospheres, gravitational lensing time delays from multiple quasar images, etc. • Relative distance estimators These (ultimately) depend on directly measured distances, and are based on the existence of types of objects that share the same intrinsic luminosity (and whose distance has been determined somehow). For example, there are types of stars that have all the same intrinsic luminosity. If the distance to a sample of these objects has been measured directly (e.g. through trigonometric parallax), then we can use these to determine the distance to a nearby galaxy by comparing their apparent brightness to those in the Milky Way. Essentially we use that log(D1/D2) = 1/5 * [(m1 –m2) - (A1 –A2)] where D1 is the distance to system 1, D2 is the distance to system 2, m1 is the apparent magnitudes of stars in S1 and S2 respectively, and A1 and A2 corrects for the absorption towards the sources in S1 and S2. Stars or objects which have the same intrinsic luminosity are known as standard candles. If the distance to such a standard candle has been measured directly, then the relative distances will have been anchored to an absolute distance scale. -

THE ORION NEBULA and ITS ASSOCIATED POPULATION C. R. O'dell

27 Jul 2001 11:9 AR AR137B-04.tex AR137B-04.SGM ARv2(2001/05/10) P1: FRK Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2001. 39:99–136 Copyright c 2001 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved THE ORION NEBULA AND ITS ASSOCIATED POPULATION C. R. O’Dell Department of Physics and Astronomy, Box 1807-B, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee 37235; e-mail: [email protected] Key Words gaseous nebulae, star formation, stellar evolution, protoplanetary disks ■ Abstract The Orion Nebula (M 42) is one of the best studied objects in the sky. The advent of multi-wavelength investigations and quantitative high resolution imaging has produced a rapid improvement in our knowledge of what is widely considered the prototype H II region and young galactic cluster. Perhaps uniquely among this class of object, we have a good three dimensional picture of the nebula, which is a thin blister of ionized gas on the front of a giant molecular cloud, and the extremely dense associated cluster. The same processes that produce the nebula also render visible the circumstellar material surrounding many of the pre–main sequence low mass stars, while other circumstellar clouds are seen in silhouette against the nebula. The process of photoevaporation of ionized gas not only determines the structure of the nebula that we see, but is also destroying the circumstellar clouds, presenting a fundamental conundrum about why these clouds still exist. 1. INTRODUCTION Although M 42 is not the largest, most luminous, nor highest surface brightness H II region, it is the H II region that we know the most about. -

Surface Photometry of Galaxies”, PASP, V.100, P.524, 1988 8

Surface photometry is a technique to measure the surface brightness distribution of extended objects (galaxies, HII regions etc.). Surface photometry : distribution of light (mass), global Surface Photometry of structure of galaxies, geometrical characteristics of galaxies, Galaxies spatial orientation, stellar populations, characteristics of dust... Surface photometry and spectroscopic observations – two Vladimir Reshetnikov major observational methods of extragalactic astronomy. [email protected] St.Petersburg State University, Russia Plan Literature 1. Introduction J. Binney, M. Merrifield “Galactic Astronomy”, Princeton 2. Methods of surface photometry University Press, 1998 3. Presentation of surface photometric data L.S. Sparke, J.S. Gallagher “Galaxies in the Universe: An 4. Standard models for early-type galaxies Introduction”, Cambridge University Press, 2000 5. Standard models for disk galaxies D. Mihalas, J. Binney “Galactic Astronomy”, W.H. Freeman and 6. Multicomponent galaxies Company, 1981 7. Influence of dust S. Okamura “Surface photometry of galaxies”, PASP, v.100, p.524, 1988 8. Results: spirals, ellipticals B. Milvang-Jensen, I. Jorgensen “Galaxy surface photometry”, 9. Sky surveys and deep fields Baltic Astronomy, v.8, p.535, 1999 10. High-redshift galaxies Introduction Introduction Standard definitions Standard definitions Definitions Definitions Surface brightness – radiative flux per unit solid angle of the The surface brightness in magnitude units is related to the image ( I f/ ∆Ω ). ∝ surface brightness in physical units of solar luminosity per square parsec by 2 2 0.4( M⊙−µ−5) 8 0.4( M⊙−µ) To a first approximation, the s.b. of an extended object is I(L⊙/pc ) = (206265) 10 = 4 .255 10 10 , independent of its distance from us since f and ∆Ω are · · where is the absolute magnitude of the Sun. -

524-544, May 1988 SURFACE PHOTOMETRY of GALAXIES

Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 100: 524-544, May 1988 SURFACE PHOTOMETRY OF GALAXIES* SADANORI OKAMURA Kiso Observatory, Tokyo Astronomical Observatory, University of Tokyo Mitake-mura, Kiso-gun, Nagano-ken, 397-01 Japan Received 1988 January 4 ABSTRACT Surface photometry of galaxies has undergone a great advance recently with the development of fast digital plate-measuring machines, powerful computers to process the huge amount of data from them, and efficient image-processing software. Further, the recent advent of charge-coupled devices (CCDs) has made the technique effective even with relatively small telescopes. Because of their very high sensitivity, especially in the red wavelength region, CCDs have opened a new era of surface photometry. The methodology of surface photometry of galaxies is reviewed and recent results are summarized. Future prospects of the technique in galaxy research are briefly discussed. Key words: surface photometry-galaxies I. Introduction JK80; Kormendy 1982, hereafter JK82; Capaccioli 1984, Surface photometry is a technique to measure the 1985, 1987; Nieto 1986). Overlap with these reviews has surface-brightness distribution of extended objects such been minimized. as galaxies and Η π regions. It is one of the oldest tech- In what follows the technical aspects are reviewed in niques in modern astronomy. The first attempt at surface Section II, recent results are summarized in Section III, photometry of galaxies dates back to Reynolds (1913). and future prospects are presented in Section IV. Comprehensive historical reviews are given by de Vau- II. Methods, Problems, and Accuracy couleurs (1979; hereafter dV79) and de Vaucouleurs (1987). A. The Night-Sky Light: Intrinsic Limitation on Surface The number of galaxies whose brightness distributions Photometry are mapped in detail has been rapidly growing. -

Galaxy Photometry

Galaxy Photometry For galaxies, we measure a surface flux, that is, the counts in each pixel. Through calibration, this is converted to flux density in Janskys (1 Jy = -26 2 10 W/m /Hz). 1 For a galaxy at some distance, d, a pixel of side D subtends an angle, α, given by r d D α D α= . d The surface brightness is the amount of light in that patch of sky divided by its area (in arsec2): Flux Jy I(r)= . α22arcsec Luminosity Recalling the relationship between flux and luminosity, Flux = , the surface π 2 brightness becomes 4d 2 F L d L L Watts = = = I(r) 22 2 2 or 2. απ4 dD 4 π D pc arcsec Which is often given in solar luminosities per parsec2. To convert this to magnitudes, recall that the apparent magnitude is a measure of flux, F m−=− m 2.5 log . 0 F 0 So the surface brightness in magnitudes per arsec2 is F α2 µ−µ =−2.5 log , 0 α2 F0 I µ−µ =−2.5 log. 0 I 0 2 EXAMPLE: For the Sun in the optical V-Band, taking I0 = 1 L/pc 2 for µ0 = 26.4 magnitudes/arcsec , yields µ=−2.5 log( I) + 26.4 mag/arcsec2 . Giving the surface brightness (in the V-band in this case), as 0.4( 26.4−µ ) L = V V IV 10 . pc2 1 From Amina Helmi’s Kapteyn course at www.astro.rug.nl/~ahelmi/teaching/gal2010/ellipt.pdf Galaxy Photometry Undergraduate ALFALFA Team AOD 6/28/2016 The total (apparent) magnitude of the galaxy is the surface brightness integrated over the entire galaxy. -

The Paper Is in Pdf Format

The Realm of the Low-Surface-Brightness Universe Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 355, 2019 c 2019 International Astronomical Union D. Valls-Gabaud, I. Trujillo & S. Okamoto, eds. DOI: 00.0000/X000000000000000X Ultra-deep imaging with amateur telescopes David Mart´ınez-Delgado1 1Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, University of Heidelberg, M¨onchhofst. 12-14, DE-69120, Heidelberg, Germany email: [email protected] Abstract. Amateur small equipment has demonstrated to be competitive tools to obtain ultra-deep imaging of the outskirts of nearby massive galaxies and to survey vast areas of the sky with unprecedented depth. Over the last decade, amateur data have revealed, in many cases for the first time, an assortment of large-scale tidal structures around nearby massive galaxies and have detected hitherto unknown low surface brightness systems in the local Universe that were not detected so far by means of resolved stellar populations or Hi surveys. In the Local Group, low-resolution deep images of the Magellanic Clouds with telephoto lenses have found some shell- like features, interpreted as imprints of a recent LMC-SMC interaction. I this review, I discuss these highlights and other important results obtained so far in this new type of collaboration between high-class astrophotographers and professional astronomers in the research topic of galaxy formation and evolution. Keywords. galaxies:general, galaxies:dwarf, galaxies:halos, telescopes 1. Introduction Within the hierarchical framework for galaxy formation, the stellar halos of massive galaxies are expected to form and evolve through a succession of mergers with low- mass systems. Numerical cosmological simulations of galaxy assembly in the Λ-Cold Dark Matter (Λ-CDM) paradigm predict that satellite disruption occurs throughout the lifetime of all massive galaxies and, as a consequence, their stellar halos at the present day should contain a wide variety of diffuse remnants of disrupted dwarf satellites. -

Elliptical Galaxies •The Brightest Galaxies in the Universe Are Ellipticals, but Also Some of the Faintest

Elliptical galaxies •The brightest galaxies in the Universe are ellipticals, but also some of the faintest. •Elliptical galaxies appear simple: roundish on the sky, the light is smoothly distributed, and they lack star formation patches or strong internal obscuration by dust. •But are they so simple? Detailed studies reveal great complexity: •shapes (from oblate to triaxial); •large range of luminosity and light concentration; •fast and slowly rotating; •cuspy and cored … Classification by luminosity • There are three classes of ellipticals, according to their luminosity: • Giant ellipticals have L > L*, where L* is the luminosity of a large galaxy, 10 L* = 2 × 10 L¯ or MB = - 20 (the Milky Way is an L* galaxy). 9 • Midsized ellipticals are less luminous, with L > 3 × 10 L¯, or MB < -18 9 • Dwarf ellipticals have luminosities L < 3 × 10 L¯ •These luminosity classes also serve to describe other properties of E galaxies (in contrast to disk galaxies, where each class be it Sa … Sd contains a wide range of sizes and luminosities). •Ellipticals come in one-size sequence: their internal properties are correlated with their total luminosity (or mass) Galaxy photometry The surface brightness of a galaxy I(x) is the amount of light on the sky at a particular point x on the image. Consider a small patch of side D in a galaxy located at a distance d. It will subtend an angle α = D/d on the sky. If the combined luminosity of all the stars in this region is L, its apparent brightness is F = L/(4πd2). Therefore the surface brightness I(x) = F/α2 = L/(4π d2) * (d/D)2 = L/(4π D2). -

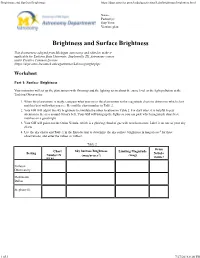

Brightness and Surface Brightness

Brightness and Surface Brightness https://dept.astro.lsa.umich.edu/ugactivities/Labs/brightness/brightness.html Name: Partner(s): Day/Time: Version: plan Brightness and Surface Brightness This document is adopted from Michigan Astronomy and edited to make it applicable for Tarleton State University, Stephenville TX, Astronomy course under Creative Common License (https://dept.astro.lsa.umich.edu/ugactivities/Labs/copyright.php) Worksheet Part 1: Surface Brightness Your instructor will set up the planetarium with Orion up and the lighting set to about the same level as the light pollution at the Tarleton Observaotry. 1. When the planetarium is ready, compare what you see in the planetarium to the magnitude charts to determine which chart matches best with what you see. Record the chart number in Table 2. 2. Your GSI will adjust the sky brightness to simulate the other locations in Table 2. For dark sites, it is helpful to pay attention to the area around Orion's belt. Your GSI will bring up the lights so you can pick which magnitude chart best matches on a good night. 3. Your GSI will point out the Orion Nebula, which is a glowing cloud of gas with new-born stars. Label it on one of your sky charts. 4. Use the sky charts and Table 1 in the Introduction to determine the sky surface brightness in mag/arcsec2 for these observations, and enter the values in Table 2. Table 2 Orion Chart Sky Surface Brightness Limiting Magnitude Setting Nebula Number/N (mag/arcsec2) (mag) visible? ELM Tarleton Observatory Downtown Dallas Stephenville 1 of 3 7/27/2016 8:00 PM Brightness and Surface Brightness https://dept.astro.lsa.umich.edu/ugactivities/Labs/brightness/brightness.html Part 2: Limiting Magnitude 5.