The Playwright and the Abbey Theatre. Phd Thesis. Ht

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

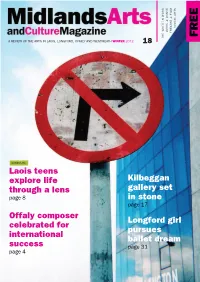

Issue 18 Midlands Arts 4:Layout 1

VISUAL ARTS MUSIC & DANCE ISSUE & FILM THEATRE FREE THE WRITTEN WORD A REVIEW OF THE ARTS IN LAOIS, LONGFORD, OFFALY AND WESTMEATH WINTER 2012 18 COVER PIC Laois teens explore life Kilbeggan through a lens gallery set page 8 in stone page 17 Offaly composer Longford girl celebrated for pursues international ballet dream success page 31 page 4 Toy Soldiers, wins at Galway Film Fleadh Midland Arts and Culture Magazine | WINTER 2010 Over two decades of Arts and Culture Celebrated with Presidential Visit ....................................................................Page 3 A Word Laois native to trend the boards of the Gaiety Theatre Midlands Offaly composer celebrated for international success .....Page 4 from the American publisher snaps up Longford writer’s novel andCulture Leaves Literary Festival 2012 celebrates the literary arts in Laois on November 9, 10............................Page 5 Editor Arts Magazine Backstage project sees new Artist in Residence There has been so Irish Iranian collaboration results in documentary much going on around production .....................................................................Page 6 the counties of Laois, Something for every child Mullingar Arts Centre! Westmeath, Offaly Fear Sean Chruacháin................................................Page 7 and Longford that County Longford writers honored again we have had to Laois teens explore life through the lens...............Page 8 up the pages from 32 to 36 just to fit Introducing Pete Kennedy everything in. Making ‘Friends’ The Doctor -

Triskele Fall 2004.Pmd

TRISKELE A newsletter of UWM’s Center for Celtic Studies Volume III, Issue II Samhain, 2004 Fáilte! Croeso! Mannbet! Kroesan! Fair Faa Ye! Welcome! Midwest ACIS Comes to Milwaukee The annual Midwest Regional meeting of the American Conference for Irish Studies (ACIS) was held on the UWM campus from Thursday, October 14, through Saturday, October 16. ACIS is an interdisciplinary scholarly organization founded in 1960. The conference was organized by José Lanters, Nancy Walczyk, and John Gleeson, under the auspices of the Center for Celtic Studies. On Thursday evening, the meeting kicked off in great style with a reception for the delegates in County Clare Irish Inn, with Irish music by Cé. In the course of the evening, James Liddy’s autobiography, The Doctor’s House (Salmon Press, 2004), fresh off the plane from Ireland, was launched, read from, toasted, sold, and sanctioned by the presence of emeritus archbishop Rembert Weakland, who had joined us for the occasion. Friday was a full day, with an exciting academic program of eight panels of four speakers each, on topics ranging from literature and history to music, art and politics. Professor Seamus Caulfield’s Frank Gleeson, Tom Kilroy, James Liddy, plenary lecture, “Neolithic Rocks to Riverdance,” accompanied by Jose Lanters, Josephine Craven, Joe slides and presented with verve and humor, gave his enthusiastic Dowling and Eamonn O’Neill audience an insight into the many and varied aspects of the archaeological excavations at Céide Fields in Co. Mayo. A reception at the Irish Cultural and Heritage Center, hosted by Charles Sheehan, Irish Consulate of Chicago, concluded the day, and included even more delights, in the form of James Fraher’s photographic images of Ireland, and enchanting music by Melanie O’Reilly and Seán O Nualláin. -

Macbeth on Three Levels Wrap Around a Deep Thrust Stage—With Only Nine Rows Dramatis Personae 14 Separating the Farthest Seat from the Stage

Weird Sister, rendering by Mieka Van Der Ploeg, 2019 Table of Contents Barbara Gaines Preface 1 Artistic Director Art That Lives 2 Carl and Marilynn Thoma Bard’s Bio 3 Endowed Chair The First Folio 3 Shakespeare’s England 5 Criss Henderson The English Renaissance Theater 6 Executive Director Courtyard-Style Theater 7 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Timeline 12 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style Courtyard Theater, 500 seats Shakespeare's Macbeth on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows Dramatis Personae 14 separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also The Story 15 features a flexible 180-seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Act by Act Synopsis 15 Center, and a Shakespeare specialty bookstall. In 2017, a new, innovative S omething Borrowed, Something New: performance venue, The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare, expanded CST's Shakespeare’s Sources 18 campus to include three theaters. The year-round, flexible venue can 1606 and All That 19 be configured in a variety of shapes and sizes with audience capacities Shakespeare, Tragedy, and Us 21 ranging from 150 to 850, defining the audience-artist relationship to best serve each production. Now in its thirty-second season, the Theater has Scholars' Perspectives produced nearly the entire Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends -

Cois Coiribe 2016

COIRIBE COIS Rio The Magazine for GOLD NUI Galway Galway 2020 MedTech in Galway A Changing Campus Alumni & Friends Autumn 2016 NUI Galway Affinity Card. You get, we give. You get a unique credit card and we give back to NUI Galway when you register and each year your Affinity card is active. Our introductory offer gives you a competitive rate of 2.9%¹ APR interest on balance transfers for first 12 months. bankofireland.com/alumni 1890 365 100 Lending criteria terms and conditions apply to all credit cards. Credit cards are liable to Government Stamp Duty of €30. Credit cannot be offered to anyone under 18 years of age. Bank of Ireland is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland. ¹Available if you don’t currently hold a credit card with Bank of Ireland, whether you have an account with us or not. At the end of the introductory period the annual interest rates revert back to 2 COIS COIRIBEthe standard rate applicable to your card at that time. OMI008172 - NUIG Affinity A4_Portrait Ad_v13.indd 1 03/08/2016 12:35 NUI Galway CONTENTS 2 FOCAL ÓN UACHTARÁN NEWS Affinity Card. 4 The Year in Pictures 6 Research Round-up 10 University News You get, we give. 14 Campus News 26 Student Success FEATURES 16 A New Direction for Sport 22 1916 – Centenary Year 4 24 NASA Mission 28 A Changing Campus - Capital Development 32 Giving Stem Cells a heartbeat 34 MedTech in Galway 24 41 TG4 @ 20 42 Galway 2020 GRADUATES 36 Aoibheann McNamara 37 Paul O’Hara 38 Grads in Silicon Valley 44 Graduations GALWAY UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION 46 Empowering Excellence ALUMNI 6 18 50 Alumni Awards 38 52 Alumni Events 56 Class Notes 64 Obituaries CONTRIBUTORS Jo Lavelle, John Fallon, Ronan McGreevy, Joyce McCreevy, Joe Connolly, Dónall Ó Braonáin, Conor McNamara, Liz McConnell, Ruth Hynes, Sheila Gorham. -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

All We Say Is 'Life Is Crazy': – Central and Eastern Europe and the Irish

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title All we say is 'Life is crazy': - Central and Eastern Europe and the Irish Stage Author(s) Lonergan, Patrick Publication Date 2009 Lonergan, P. (2009) ' All we say is 'Life is Crazy': - Central and Publication Eastern Europe and the Irish Stage' In: Maria Kurdi, Literary Information and Cultural Relations Between Ireland and Hungary and Central and Eastern Europe' (Eds.) Dublin: Carysfort Press. Publisher Dublin: Carysfort Press Link to publisher's http://www.carysfortpress.com/ version Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/5361 Downloaded 2021-09-28T21:11:04Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. All We Say is ‘Life is Crazy’: – Central and Eastern Europe and the Irish Stage Patrick Lonergan If you had visited the Abbey Theatre during 2007, you might have seen a card displayed prominently in its foyer. ‘Join Us,’ it says, its purpose being to convince visitors to become Members of the Abbey – to donate money to the theatre and, in return, to get free tickets for productions, to have their names listed in show programmes, and to gain access to special events. The choice of image to attract potential donors is easy to understand (Figure 1). The woman, we see, has reached into a chandelier to retrieve a letter, and we can tell from her expression that the discovery she’s made has both surprised and delighted her. Why is she so happy? What does the letter say? And who is that strange man, barely visible, holding her up at such an unusual angle? As well as being eye-catching, the image is also an interesting analogue for the experience of watching great drama. -

2017 Katie Roche, Research Pack

ABBEY THEATRE RESEARCH PACK KATIE ROCHE TERESA DEEVY Researched and compiled by Marie Kelly (School of Music and Theatre, University College Cork) CONTRIBUTORS Fiona Becket, University of Leeds Caroline Byrne, theatre director Amanda Coogan, performance artist Úna Kealy, Waterford Institute of Technology Marie Kelly, University College Cork Cathy Leeney, University College Dublin Chris Morash, Trinity College Dublin Kate McCarthy, Waterford Institute of Technology Barbara McCormack, Hugh Murphy, Valerie Payne, Róisín Berry, Maynooth University Morna Regan, dramaturg/writer Eibhear Walshe, University College Cork With special thanks to the Abbey Theatre Archive and the Teresa Deevy Archive, Special Collections & Archives, Maynooth University, Co. Kildare. For more information see https://www.abbeytheatre. ie/about/archive/ and www.deevy.nuim.ie Cover Image: Caoilfhionn Dunne as Katie Roche © Ros Kavanagh KATIE ROCHE, RESEARCH PACK 2 WELCOME PHIL KINGSTON From 26 August to 23 September 2017, the dramaturgy and Caroline Byrne’s expressionistic Abbey Theatre presented a major revival of staging turned this Katie Roche into far more Teresa Deevy’s ground-breaking play Katie than a reverential museum piece. The audiences Community and Roche. It was over 80 years since this daring saw a specific, thrilling and thought provoking Education Manager meditation on freedom, duty and pride in take on Deevy’s classic story. Coincidentally at the life of a young woman made its world the same time another artist, Amanda Coogan, premiere on the Abbey stage. presented a performance art based response to Deevy’s work in collaboration with Dublin In its initial press release the Abbey explicitly Theatre of the Deaf in Talk Real Fine, Just Like A recognised that the political climate had Lady. -

Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980S Irish Theatre

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Provoking performance: challenging the people, the state and the patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Author(s) O'Beirne, Patricia Publication Date 2018-08-28 Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/14942 Downloaded 2021-09-27T14:54:59Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Candidate: Patricia O’Beirne Supervisor: Dr. Ian Walsh School: School of Humanities Discipline: Drama and Theatre Studies Institution: National University of Ireland, Galway Submission Date: August 2018 Summary of Contents: Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre This thesis offers new perspectives and knowledge to the discipline of Irish theatre studies and historiography and addresses an overlooked period of Irish theatre. It aims to investigate playwriting and theatre-making in the Republic of Ireland during the 1980s. Theatre’s response to failures of the Irish state, to the civil war in Northern Ireland, and to feminist and working-class concerns are explored in this thesis; it is as much an exploration of the 1980s as it is of plays and playwrights during the decade. As identified by a literature review, scholarly and critical attention during the 1980s was drawn towards Northern Ireland where playwrights were engaging directly with the conflict in Northern Ireland. This means that proportionally the work of many playwrights in the Republic remains unexamined and unpublished. -

Index of Castlebar Parish Magazine 1971

Index of Castlebar Parish Magazine 1971 1. Parish Roundup & review of the past twelve months. Tom Courell 2. St. Gerald’s College – Short History Brother Vincent 3. Tribute to Walter Cowley, Vocational Teacher Sean O’Regan 4. Memories from School – Articles & Poems A) An old man remembers French Hill 1798. B) Poem “Old School Round the Corner” by pupils of 6th class, Errew School. C) Poem “ The Mall in Winter” by Ann Kelly, aged 12. D) Poem “ Nightfall in Sionhill” by Bridie Flannery, aged 12. E) Poem “Tanseys Bus Stop” by Gabrielle O’Farrell, aged 11. F) Poem “The Mall in November” by Kathryn Kilroy, aged 12. G) Poem “ The Station” by Eimear O’Meara, aged 11. H) Poem “St. Anthony’s School” by Mairin Feighan, aged 11. I) The Gossip in Town by Grainne Fadden, aged 12. J) Kinturk Castle by Ann Garvey, Carmel Mugan & Gabrielle Thomas. K) Description of Ballyheane by Geraldine Kelly, aged 12. L) Sean na Sagart by pupils of 5th class, Ballyheane N.S. M) Derryharrif by Bernadette Walsh. N) Ballinaglough by Ann Moran, aged 11. O) Murder at Breaffy by John Walsh & Liam Mulcahy. P) History of Charles Street, Castlebar by Raymond Fallon, aged 12. Photographs; 1) New St.Gerald’s College, Newport Road, Castlebar ( Front Cover ) 2) St.Gerald’s College, Chapel Street, Castlebar 3) Teaching Staff of St.Gerald’s College, Castlebar, 1971. Parish Sport : Gaelic Games, Rugby & Camogie. Castlebar Associations Review : London, Birmingham & Manchester Births, Deaths & Marriages for 1971 are also included. Index of Castlebar Parish Magazine 1972 1. Parish Review of the past twelve months. -

The Afterlives of the Irish Literary Revival

The Afterlives of the Irish Literary Revival Author: Dathalinn Mary O'Dea Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104356 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2014 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of English THE AFTERLIVES OF THE IRISH LITERARY REVIVAL a dissertation by DATHALINN M. O’DEA submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2014 © copyright by DATHALINN M. O’DEA 2014 Abstract THE AFTERLIVES OF THE IRISH LITERARY REVIVAL Director: Dr. Marjorie Howes, Boston College Readers: Dr. Paige Reynolds, College of the Holy Cross and Dr. Christopher Wilson, Boston College This study examines how Irish and American writing from the early twentieth century demonstrates a continued engagement with the formal, thematic and cultural imperatives of the Irish Literary Revival. It brings together writers and intellectuals from across Ireland and the United States – including James Joyce, George William Russell (Æ), Alice Milligan, Lewis Purcell, Lady Gregory, the Fugitive-Agrarian poets, W. B. Yeats, Harriet Monroe, Alice Corbin Henderson, and Ezra Pound – whose work registers the movement’s impact via imitation, homage, adaptation, appropriation, repudiation or some combination of these practices. Individual chapters read Irish and American writing from the period in the little magazines and literary journals where it first appeared, using these publications to give a material form to the larger, cross-national web of ideas and readers that linked distant regions. -

J This Week Two Sections 20 Pages COVERING Arne

UONliOUTH JO. HISTORICAL. ASS!| . , f a s s a o u ) . »HV.f.. J ■ X This Week COVERING / TOVVNSHIPB OF Two Sections HOLMDEL, MADISON MARLBORO, MATAWAN AND 20 Pages MATAWAN BOROUGH Member Member 90th YEAR — 15th WEEK National Editorial Association MATAWAN, N. J., THURSDAY, OCTOBER 9, 1958 New Jeney Preu Asiodition Single Copy Ten CenU Arne Kalma Test Cleanup Day Salary Ordinance Something Has Been Added At MHS Football Field Sawmill In Residential Zone On MatawanCoancUwoman Mrs. Genevieve Donnell announced Semi-Finalist Tuesday that the semt-a a n u a 1 Gains Adoption Middlesex Rd. Finally Rejected ‘,Cieanup OayJHa Matawan wtH 10,000 Highest To be held ThursdayrOctn«r“ An Township Sets Madison Township Committee Rules Out Compete Once Again residents of the borough are urg Date For Vote Recommendation For Zoning Variance i ed to co-operate .by making a Principal Luther Foster of Mata general cleanup campaign in An ordinance establishing a max Nn sawmill will be located and wan High School announced that their cellars and attics. imum range of salaries for mem Miss Joan Visits operated on the lands of Frederick Arne Kalma, a senior student, has Cleanup day presents an oppor nnd Wllllnm Formnn, Middlesex been named a semi-finalist in the tunity (or borough residents to bers of the police department, rep Nearly 1000 youngsters nnd Rd. Mnyor Jolm L. Clinmborlaln 1958-59 National Merit Scholarship dear out trash and refuse which resenting an Increase of $700 per adults overflowed the J. J. New nniiounccd thnt the township com- competition. will be carted away by the gar man, was introduced yesterday by berry Co., storo, West Front St., inlttec Monday wns awuro tlie run- As a Kemi-finalist.